Herpetofauna Diversity and Microenvironment Correlates Across

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 the Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund Provides Financial Support to Species Conservation Projects Worldwide

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund provides financial support to species conservation projects worldwide. In 2016 the Fund supported 172 projects in 69 different countries with $1,523,118. We must also remember that each of us can make a contribution to conservation in our own way. We are all potential conservationists; you do not need to risk life and limb in a far corner of the world to play your part. We are all conservation. Printed on Forest Stewardship Council certified paper The Fund provides grants directly to conservationists in the field, and in doing so hopes to provide these individuals and their projects with the necessary exposure to win further financial and material support from other donors. We are glad to report that many of our grant recipients have attributed their progress in attracting further financial support directly to their successful application to the Fund. Efforts to understand and preserve This report presents a selection of the the environment around us come in a projects the Fund has recently supported, We are also delighted to reveal that two of the projects featured multitude of forms. Whether it is conducting featuring species as diverse in their biology herein report the re-discovery of species not seen alive in the a multi-million dollar conservation and scale as the mighty Asian elephant wild for decades: Cropan’s boa in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil programme, providing funds to support and the humble Red-finned blue-eye. It also (missing for 64 years) and the tiny, coin-sized Cave squeaker species conservation projects, or the aims to celebrate the people behind these of Zimbabwe’s Chimanimani mountains (not seen for 50 years). -

Petition to List 53 Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States As Threatened Or Endangered Species Under the Endangered Species Act

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST 53 AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE UNITED STATES AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY JULY 11, 2012 1 Notice of Petition _____________________________________________________________________________ Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Nicole Alt, Chief Division of Conservation and Classification, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] AUTHORS Collette L. Adkins Giese Herpetofauna Staff Attorney Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 339 Circle Pines, MN 55014-0339 [email protected] 2 D. Noah Greenwald Endangered Species Program Director Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] Tierra Curry Conservation Biologist P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] PETITIONERS The Center for Biological Diversity. The Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) is a non- profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center is supported by over 375,000 members and on-line activists throughout the United States. -

Taxonomic Checklist of Amphibian Species Listed Unilaterally in The

Taxonomic Checklist of Amphibian Species listed unilaterally in the Annexes of EC Regulation 338/97, not included in the CITES Appendices Species information extracted from FROST, D. R. (2013) “Amphibian Species of the World, an online Reference” V. 5.6 (9 January 2013) Copyright © 1998-2013, Darrel Frost and The American Museum of Natural History. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction for commercial purposes prohibited. 1 Species included ANURA Conrauidae Conraua goliath Annex B Dicroglossidae Limnonectes macrodon Annex D Hylidae Phyllomedusa sauvagii Annex D Leptodactylidae Leptodactylus laticeps Annex D Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus Annex B Pelophylax shqipericus Annex D CAUDATA Hynobiidae Ranodon sibiricus Annex D Plethodontidae Bolitoglossa dofleini Annex D Salamandridae Cynops ensicauda Annex D Echinotriton andersoni Annex D Laotriton laoensis1 Annex D Paramesotriton caudopunctatus Annex D Paramesotriton chinensis Annex D Paramesotriton deloustali Annex D Paramesotriton fuzhongensis Annex D Paramesotriton guanxiensis Annex D Paramesotriton hongkongensis Annex D Paramesotriton labiatus Annex D Paramesotriton longliensis Annex D Paramesotriton maolanensis Annex D Paramesotriton yunwuensis Annex D Paramesotriton zhijinensis Annex D Salamandra algira Annex D Tylototriton asperrimus Annex D Tylototriton broadoridgus Annex D Tylototriton dabienicus Annex D Tylototriton hainanensis Annex D Tylototriton kweichowensis Annex D Tylototriton lizhengchangi Annex D Tylototriton notialis Annex D Tylototriton pseudoverrucosus Annex D Tylototriton taliangensis Annex D Tylototriton verrucosus Annex D Tylototriton vietnamensis Annex D Tylototriton wenxianensis Annex D Tylototriton yangi Annex D 1 Formerly known as Paramesotriton laoensis STUART & PAPENFUSS, 2002 2 ANURA 3 Conrauidae Genera and species assigned to family Conrauidae Genus: Conraua Nieden, 1908 . Species: Conraua alleni (Barbour and Loveridge, 1927) . Species: Conraua beccarii (Boulenger, 1911) . Species: Conraua crassipes (Buchholz and Peters, 1875) . -

2012 Petition to List 53 Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States As

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST 53 AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE UNITED STATES AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY JULY 11, 2012 1 Notice of Petition _____________________________________________________________________________ Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Nicole Alt, Chief Division of Conservation and Classification, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] AUTHORS Collette L. Adkins Giese Herpetofauna Staff Attorney Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 339 Circle Pines, MN 55014-0339 [email protected] 2 D. Noah Greenwald Endangered Species Program Director Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] Tierra Curry Conservation Biologist P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] PETITIONERS The Center for Biological Diversity. The Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) is a non- profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center is supported by over 375,000 members and on-line activists throughout the United States. -

Project Anuran Phase I: Main Report

Project Anuran Phase I: Main Report An ecological research project concerned with the assessment and monitoring of anuran populations in the region around Las Cuevas, Chiquibul Forest Reserve, Belize. BY Toby Gardner, Emily Fitzherbert, Nick Hill and Lorry Williams June 2001 Project Anuran Institute of Ecology and Resource Management University of Edinburgh Darwin Building Kings Buildings Mayfield Road EH9 3JU Edinburgh, Scotland Email: [email protected] Website: www.projectanuran.org 2 Summary In the last 20 years the scientific community has become increasingly concerned following a growing number of reports documenting global amphibian declines. Observations of frequently catastrophic amphibian declines in areas of the world previously thought to be undisturbed by man, has led to the suggestion that human-induced global agents are responsible for declines. The fact that amphibians play in an integral role in the functioning of many ecosystems, points to the potentially drastic consequences of large-scale population declines. Furthermore, due to their bi-phasic lifestyle, existing in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats, coupled with their highly permeable skin, they can act as excellent indicators of environmental health – a fact that bears worrying implications for humans in light of their increasing demise. In order to resolve the phenomenon of declining amphibian populations, and consequently take appropriate conservation action, there is a desperate need for long-term and intensive monitoring programs. The aim of Project Anuran is to undertake a comprehensive monitoring program of an entire community of amphibians across a suite of study sites, in the region of the neotropical research station at Las Cuevas, Belize. Using standard protocols of vocalisation surveys, and nocturnal visual searches detailed data was collected during summer 2000 on the diversity, relative abundance, and habitat associations of local amphibian populations. -

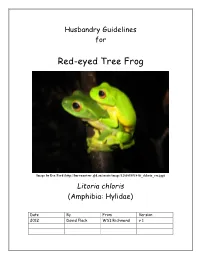

Red-Eyed Tree Frog

Husbandry Guidelines for Red-eyed Tree Frog Image by Eva Ford (http://burrumriver.qld.au/assets/image/1281853538-lit_chloris_eva.jpg) Litoria chloris (Amphibia: Hylidae) Date By From Version 2012 David Flack WSI Richmond v 1 DISCLAIMER This husbandry manual was produced by the author/compiler for TAFE NSW –Western Sydney Institute, Richmond College, NSW, Australia as part assessment for completion of Certificate III in Captive Animals, course number 1068, RUV30204. These guidelines are the result of student project work and due care should be taken in the interpretation of information herein. No responsibility is assumed for any loss or damage that results from the use of this manual. This document is a utility document, and as such, is a “work in progress”, so any contributions or enhancements to this manual is welcomed and appreciated. 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS Occupational Health & Safety Rating: Innocuous (Low Risk) Potential Zoonotic Diseases Although the overall frequency of transmission of disease-producing agents from frogs to humans is low, humans can contract a number of diseases from working with frogs. This is typically due to ingestion of infected frog tissues or from contaminated aquarium water. Contamination of open wounds is another means of transmission of frog zoonotic disease. Many bacteria and protozoa are opportunistic; a human host with a compromised immune system are the persons most at risk of contracting frog zoonoses. If you have a pre- existing health condition or are taking immune-compromising medications, consult your general practitioner before working with frogs. Following is a list of frog zoonoses: Salmonella: A bacteria which inhabits the intestinal tract of various animals and humans.