Stories of Involuntary Resettlement from Gaadhoo Island, Maldives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electricity Needs Assessment

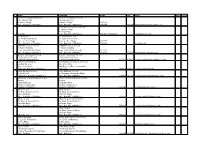

Electricity needs Assessment Atoll (after) Island boxes details Remarks Remarks Gen sets Gen Gen set 2 Gen electricity electricity June 2004) June Oil Storage Power House Availability of cable (before) cable Availability of damage details No. of damaged Distribution box distribution boxes No. of Distribution Gen set 1 capacity Gen Gen set 1 capacity Gen set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Gen set 2 capacity set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Total no. of houses Number of Gen sets Gen of Number electric cable (after) cable electric No. of Panel Boards Number of DamagedNumber Status of the electric the of Status Panel Board damage Degree of Damage to Degree of Damage to Degree of Damaged to Population (Register'd electricity to the island the to electricity island the to electricity Period of availability of Period of availability of HA Fillladhoo 921 141 R Kandholhudhoo 3,664 538 M Naalaafushi 465 77 M Kolhufushi 1,232 168 M Madifushi 204 39 M Muli 764 134 2 56 80 0001Temporary using 32 15 Temporary Full Full N/A Cables of street 24hrs 24hrs Around 20 feet of No High duty equipment cannot be used because 2 the board after using the lights were the wall have generators are working out of 4. reparing. damaged damaged (2000 been collapsed boxes after feet of 44 reparing. cables,1000 feet of 29 cables) Dh Gemendhoo 500 82 Dh Rinbudhoo 710 116 Th Vilufushi 1,882 227 Th Madifushi 1,017 177 L Mundoo 769 98 L Dhabidhoo 856 130 L Kalhaidhoo 680 94 Sh Maroshi 834 166 Sh Komandoo 1,611 306 N Maafaru 991 150 Lh NAIFARU 4,430 730 0 000007N/A 60 - N/A Full Full No No 24hrs 24hrs No No K Guraidhoo 1,450 262 K Huraa 708 156 AA Mathiveri 73 2 48KW 48KW 0002 48KW 48KW 00013 breaker, 2 ploes 27 2 some of the Full Full W/C 1797 Feet 24hrs 18hrs Colappes of the No Power house, building intact, only 80KW generator set of 63A was Distribution south east wall of working. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

Private Health Facilities Registered Under Ministry of Health Tuesday, March 06, 2018

Ministry of Health Male, Republic of Maldives Private Health Facilities Registered under Ministry of Health Tuesday, March 06, 2018 S/no Reg No. Catagory Clinic Name Clinic Address Clinic Phone No Registered Date 1 HF-10/ALP/PVT/006 Medical Clinic Azmi Naeem Medical & Diagnostic Centre M. Misruvaage, Shaariuvarudhee Magu, Male' 3325979 09.10.1991 2 HF-10/ALP/PVT/007 Hospital ADK Hospital Sosun Magu, Male' 3313553 15.03.1996 3 HF-10/ALP/PVT/009 Medical Clinic The Clinic H. Shady Palm, Hithafinivaa magu, Male' 3323207 18.09.1994 4 HF-10/ALP/PVT/012 Medical Clinic Crescent Medical Services G. Hithifaru, Majeedhee Magu, Male' 3317411 14.09.1997 5 HF-10/ALP/PVT/013 Medical Clinic Poly Clinic Ma. Ran Ihi, Chaandhany Magu, Male' 3314647 14.07.1997 6 HF-10/ALP/PVT/014 Dental Clinic Dental Care Centre Ma. Meyvaagasdhoshuge (1st floor), Joashee Hingun, Male' 3328446 02.07.1998 7 HF-10/ALP/PVT/016 Medical Clinic Family Planning Centre Kulunu Vehi, Buruzu Magu, Male' 26.10.1998 8 HF-10/ALP/PVT/019 Medical Clinic Imperial Medical Centre G. Chaman, Lonuziyaarai Magu, Male' 33,166,003,336,887 13.10.1999 9 HF-10/ALP/PVT/021 Medical Clinic Royal Island Medical Centre Royal Island Resort, Baa Atoll 6600088, 6600099 12.06.2001 10 HF-10/ALP/PVT/023 Medical Clinic Kulhudhuffushi Medical Centre Fithuroanuge, Hdh. Kulhudhuffushi 08.01.2002 11 HF-10/ALP/PVT/025 Medical Clinic Central Clinic Ma. Dhilleevilla, Majeedhee Magu, Male' 3312221, 3328710, 10.06.2002 12 HF-10/ALP/PVT/026 Dental Clinic Smiles Dental Care Ma. -

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Public Disclosure Authorized TSUNAMI IMPACT AND RECOVERY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT NEEDS ASSESSMENT WORLD BANK - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK - UN SYSTEM ki QU0 --- i 1 I I i i i i I I I I I i Maldives Tsunami: Impact and Recovery. Joint Needs Assessment by World Bank-ADB-UN System Page 2 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DRMS Disaster Risk Management Strategy GDP Gross Domestic Product GoM The Government of Maldives IDP Internally displaced people IFC The International Finance Corporation IFRC International Federation of Red Cross IMF The International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation MEC Ministry of Environment and Construction MFAMR Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture, and Marine Resources MOH Ministry of Health NDMC National Disaster Management Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization PCB Polychlorinated biphenyls Rf. Maldivian Rufiyaa SME Small and Medium Enterprises STELCO State Electricity Company Limited TRRF Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Fund UN United Nations UNFPA The United Nations Population Fund UNICEF The United Nations Children's Fund WFP World Food Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a Joint Assessment Team from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the United Nations, and the World Bank. The report would not have been possible without the extensive contributions made by the Government and people of the Maldives. Many of the Government counterparts have been working round the clock since the tsunami struck and yet they were able and willing to provide their time to the Assessment team while also carrying out their regular work. It is difficult to name each and every person who contributed. -

Detailed Island Risk Assessment in Maldives, L

Detailed Island Risk Assessment in Maldives Volume III: Detailed Island Reports L. Gan – Part 1 DIRAM team Disaster Risk Management Programme UNDP Maldives December 2007 Table of contents 1. Geographic background 1.1 Location 1.2 Physical Environment 2. Natural hazards 2.1 Historic events 2.2 Major hazards 2.3 Event Scenarios 2.4 Hazard zones 2.5 Recommendation for future study 3. Environment Vulnerabilities and Impacts 3.1 General environmental conditions 3.2 Environmental mitigation against historical hazard events 3.3 Environmental vulnerabilities to natural hazards 3.4 Environmental assets to hazard mitigation 3.5 Predicted environmental impacts from natural hazards 3.6 Findings and recommendations for safe island development 3.7 Recommendations for further study 4. Structural vulnerability and impacts 4.1 House vulnerability 4.2 Houses at risk 4.3 Critical facilities at risk 4.4 Functioning impacts 4.5 Recommendations for risk reduction 2 1. Geographic background 1.1 Location Gan is located on the eastern rim of Laamu Atoll, at approximately 73° 31' 50"E and 1° 52' 56" N, about 250 km from the nations capital Male’ and 3.5 km from the nearest airport, Kadhdhoo (Figure 1.1). Gan is the largest island in terms of land area and population amongst 13 inhabited islands of Laamu atoll. It’s nearest inhabited islands are Kalhaidhoo (7 km), Mundoo (10 km) and Atoll Capital Fonadhoo (10 km). Gan forms part of a stretch of 4 islands connected through causeways and bridges and is the second largest group of islands connected in this manner with a combined land area of 9.4km 2. -

Energy Supply and Demand

Technical Report Energy Supply and Demand Fund for Danish Consultancy Services Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources Maldives Project INT/99/R11 – 02 MDV 1180 April 2003 Submitted by: In co-operation with: GasCon Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report Map of Location Energy Consulting Network ApS * DTI * Tech-wise A/S * GasCon ApS Page 2 Date: 04-05-2004 File: C:\Documents and Settings\Morten Stobbe\Dokumenter\Energy Consulting Network\Løbende sager\1019-0303 Maldiverne, Renewable Energy\Rapporter\Hybrid system report\RE Maldives - Demand survey Report final.doc Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Full Meaning CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEN European Standardisation Body CHP Combined Heat and Power CO2 Carbon Dioxide (one of the so-called “green house gases”) COP Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention of Climate Change DEA Danish Energy Authority DK Denmark ECN Energy Consulting Network elec Electricity EU European Union EUR Euro FCB Fluidised Bed Combustion GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green house gas (principally CO2) HFO Heavy Fuel Oil IPP Independent Power Producer JI Joint Implementation Mt Million ton Mtoe Million ton oil equivalents MCST Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology MOAA Ministry of Atoll Administration MFT Ministry of Finance and Treasury MPND Ministry of National Planning and Development NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NGO Non-governmental organization PIN Project Identification Note PPP Public Private Partnership PDD Project Development Document PSC Project Steering Committee QA Quality Assurance R&D Research and Development RES Renewable Energy Sources STO State Trade Organisation STELCO State Electric Company Ltd. -

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives A review by R.C. Anderson and Hudha Ahmed Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Republic of Maldives and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1993 Tuna fishing is the most important fisheries activity in the Maldives. Shark fishing is oneof the majorsecondary fishing activities. A large proportion of Maldivian fishermen fish for shark at least part-time, normally during seasons when the weather is calm and tuna scarce. Most shark products are exported, with export earnings in 1991 totalling MRf 12.1 million. There are three main shark fisheries. A deepwater vertical longline fishery for Gulper Shark (Kashi miyaru) which yields high-value oil for export. An offshore longline and handline fishery for oceanic shark, which yields fins andmeat for export. And an inshore gillnet, handline and longline fishery for reef and othe’r atoll-associated shark, which also yields fins and meat for export. The deepwater Gulper Shark stocks appear to be heavily fished, and would benefit from some control of fishing effort. The offshore oceanic shark fishery is small, compared to the size of the shark stocks, and could be expanded. The reef shark fisheries would probably run the risk of overfishing if expanded very much more. Reef shark fisheries are asource of conflict with the important tourism industry. ‘Shark- watching’ is a major activity among tourist divers. It is roughly estimated that shark- watching generates US $ 2.3 million per year in direct diving revenue. It is also roughly estimated that a Grey Reef Shark may be worth at least one hundred times more alive at a dive site than dead on a fishing boat. -

MMRP Laamu Atoll Annual Report 2019

Maldivian Manta Ray Project LAAMU ATOLL | ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Conservation through research, education, and collaboration - The Manta Trust www.mantatrust.org The Manta Trust is a UK and US-registered charity, formed in 2011 to co-ordinate global research and conservation efforts WHO ARE THE around manta rays. Our vision is a world where manta rays and their relatives thrive within a globally healthy marine ecosystem. MANTA TRUST? The Manta Trust takes a multidisciplinary approach to conservation. We focus on conducting robust research to inform important marine management decisions. With a network of over 20 projects worldwide, we specialise in collaborating with multiple parties to drive conservation as a collective; from NGOs and governments, to businesses and local communities. Finally, we place considerable effort into raising awareness of the threats facing mantas, and educating people about the solutions needed to conserve these animals and the wider underwater world. Conservation through research, education and collaboration; an approach that will allow the Manta Trust to deliver a globally sustainable future for manta rays, their relatives, and the wider marine environment. Formed in 2005, the Maldivian Manta Ray Project (MMRP) is the founding project of the Manta Trust. It consists of a country- wide network of dive instructors, biologists, communities and MALDIVIAN MANTA tourism operators, with roughly a dozen MMRP staff based RAY PROJECT across a handful of atolls. The MMRP collects data around the country’s manta population, its movements, and how the environment and tourism / human interactions affect them. Since its inception, the MMRP has identified over 4,942 different individual reef manta rays, from more than 70,000 photo-ID sightings. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2 019 Photo Credit © Leanna Crowley

ANNUAL REPORT 2 019 Photo credit © Leanna Crowley credit © Leanna Photo Front cover photo © Alex Mustard Every picture tells a story through which we In its second year, MUI has made incredible happened, more people will realize the importance hope to educate, inspire, and do our part to achievements towards our goal of protecting the of conservation, sustainability, and wellness; more help save the planet. The team and I strive to Laamu Atoll. The teamwork and determination people will choose to travel to places which leave OUR share our passion for the incredible life that brought about new scientific discoveries, incredible them in awe and full of gratitude for nature’s beauty; exists right here in Laamu, and we hope to experiences for our guests and invaluable and more people will work with companies and inspire others to join us on these adventures. partnerships within our wonderful local community. organizations that inspire them to take action in their With profound thanks and gratitude to our owners, personal lives to make the world a better place. In Our conservation story began the same day our guests, our supporters, our hosts, and Six Senses pursuit of making this wish a reality, myself and the Six Senses Laamu first opened its doors in Hotels Resorts & Spas, we have been able to start rest of the MUI team commit to continuously inspiring 2011. Sustainability, wellness (for people making our goals a reality and we have ambitious others, continuously driving action, and continuously STORY and the planet), and marine conservation plans to achieve much more in the years to come. -

Untitled Spreadsheet

# Name Company Phone Fax Email Atoll Island 100 Percent MaldivesPvt Ltd 100 Percent MaldivesPvt Ltd H.Bodukunnaruge H.Bodukunnaruge Janavaree Magu Janavaree Magu 3301515 1Male', Republic of Maldives Male', Republic of Maldives 7784545 [email protected] Development Solutions Pvt Ltd M. Piyaajee Aage Muranga Magu 226 Atolls Male', Republic of Maldives 7772 526 / 7963368 [email protected] 960 Discover 960 Discover Pvt Ltd Ma. Florifer (2nd Floor) Ma. Florifer (2nd Floor) Majeedeedhee Magu Majeedeedhee Magu 3000960 3Male', Republic of Maldives Male', Republic of Maldives 7920960 [email protected] AAABAAA Travels Pvt Ltd AAABAAA Travels Pvt Ltd M. Marina Building M. Marina Building Kolige Umar Maniku Goalhi Kolige Umar Maniku Goalhi 7901995 4Male', Republic of Maldives Male', Republic of Maldives 3006920 [email protected] Absolute Hideaways Pvt Ltd Absolute Hideaways Pvt Ltd Beach Tower, 1st Floor Beach Tower, 1st Floor 5Boduthakurufaanu Magu Boduthakurufaanu Magu [email protected] Addu Travel Ventures Blue Builders International Pvt Ltd Building No: 302 Naseemee Villa Gan , Seenu Atoll Maradhoo Feydhoo , Seenu Atoll 6Addu City , Republic of Maldives Addu City [email protected] Adore Maldives Pvt Ltd Adore Maldives Pvt Ltd Lot No:11031 G. Finiyaage, Neeloafaru Magu 7Hulhumale', Republic of Maldives Male', Republic of Maldives [email protected] Adventure Travel Maldives Pvt Ltd Adventure Travel Maldves Pvt Ltd Muraka Muraka Kulhibalaamagu Kulhibalaa Magu Fulidhoo, Vaavu Atoll Fulidhoo, Vaavu Atoll 8Republic of Maldives Republic of Maldives 7999341 [email protected] Afflux Pvt Ltd Afflux Pvt Ltd Ma. West Snow, 1st Floor Ma. West Snow, 1st Floor Kurikeela Magu Kurikeela Magu 9Male', Republic of Maldives Male', Republic of Maldives 7556037 reservations@affluxtravel.com Afflux Pvt Ltd Afflux Pvt Ltd ( C-0340/2016) Ma. -

"Rights" Side of Life

THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY 1 2 THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF THE MALDIVES THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY SURVEY REPORT This survey was sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme, Maldives and the report written by Peter Hosking, Senior Consultant, UNDP THE “RIGHTS” SIDE OF LIFE - A BASELINE HUMAN RIGHTS SURVEY 3 Foreword This is the first general human rights survey undertaken in the Maldives. The information it contains about Maldivians’ awareness of the Human Rights Commission, and their knowledge about and attitudes towards human rights will form the Commission’s priorities in the years ahead. The events of September 2003 (riots in the prison and the streets of Male’) led to the announcement by the President, on June 9, 2004, of a programme of democratic reforms. Along with the establishment of the HRCM were proposals to create an independent judiciary and an independent Parliament. Once in place, these reforms will herald a new era for the Maldives, where human rights are respected by the authorities and enjoyed by all. To date, only limited progress has been made with the reform programme. Even in relation to the Commission, although it was established on Human Rights Day, 10 December 2003, by decree, there have been delays in passing its founding law. Then there were deficiencies in the law when it was passed and amendments are required. There has also been a delay in the appointment of the Commission’s members. While this situation is greatly inhibiting the Commission’s ability to function at full capacity, some activities have been possible, including the undertaking of this baseline survey with the generous assistance of UNDP.