Leisland of Dominica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Names and Addresses of Registering and Assistant Registering Officers

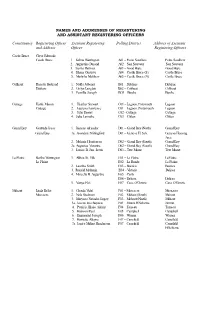

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF REGISTERING AND ASSISTANT REGISTERING OFFICERS Constituency Registering Officer Assistant Registering Polling District Address of Assistant and Address Officer Registering Officers Castle Bruce Cleve Edwards Castle Bruce 1. Kelma Warrington A01 – Petite Soufriere Petite Soufriere 2. Augustina Durand A02 – San Sauveur San Sauveur 3. Sasha Darroux A03 – Good Hope Good Hope 4. Shana Gustave A04 – Castle Bruce (S) Castle Bruce 5. Marlisha Matthew A05 – Castle Bruce (N) Castle Bruce Colihaut Rosette Bertrand 1. Nalda Jubenot B01 – Dublanc Dublanc Dublanc 2. Gislyn Langlais B02 – Colihaut Colihaut 3. Fernillia Joseph BO3 – Bioche Bioche Cottage Hartie Mason 1. Heather Stewart C01 – Lagoon, Portsmouth Lagoon Cottage 2. Laurena Lawrence C01 – Lagoon ,Portsmouth Lagoon 3. Julie Daniel C02 - Cottage Cottage 4. Julia Lamothe C03 – Clifton Clifton Grand Bay Gertrude Isaac 1. Ireneus Alcendor D01 – Grand Bay (North) Grand Bay Grand Bay 1a. Avondale Shillingford D01 – Geneva H. Sch. Geneva Housing Area 2. Melanie Henderson D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 2a. Augustus Victorine D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 3. Louise B. Jno. Lewis D03 – Tete Morne Tete Morne La Plaine Bertha Warrington 1. Althea St. Ville E01 – La Plaine LaPlaine La Plaine E02 – La Ronde La Plaine 2. Laurina Smith E03 – Boetica Boetica 3. Ronald Mathurin E04 - Victoria Delices 4. Marcella B. Augustine E05 – Carib E06 – Delices Delices 5. Vanya Eloi E07 – Case O’Gowrie Case O’Gowrie Mahaut Linda Bellot 1. Glenda Vidal F01 – Massacre Massacre Massacre 2. Nola Stedman F02 – Mahaut (South) Mahaut 3. Maryana Natasha Lugay F03- Mahaut (North) Mahaut 3a. Josette Jno Baptiste F03 – Jimmit H/Scheme Jimmit 4. -

Généalogie Et Histoire De La Caraïbe

Généalogie et Histoire de la Caraïbe " Return of produce given in under the General Tax bill of 1827 with the number of items attached to each Estate according to the last triennial return. [ From the Dominica Almanac 1828”] (Relevé des produits établi d’après le Livre Général des Taxes de 1827 avec le nombre d’éléments rattaché à chaque propriété selon le dernier relevé trisannuel .) [D’APRÉS LE DOMINICA ALMANACH 1828] Légendes : gal. = gallon (4,54609 litres); lbs = pounds (0,453592338 kg) source Wikipedia Estate : propriété, habitation. Entre parenthèses : variante de lecture Parish of St.George = Roseau Estates N° of Slaves Sugar (lbs) Rum (gal.) Molasses (gal.) Coffee (lbs) Arnaud, J.P. 10 400 Armatrading, Ann 4 878 André, Joseph 26 960 Beaubois, Chevalier 106 67500 3500 Bodet, M.F. 12 2450 Benjamin, Delamare 40 4767 Blondel, Veuve 30 2250 Barron J.W. 3 210 Corinth Estate 35 2925 Couché, Jeremie 3 700 Chopin Rosette 61 5325 De Beltgens, Le Vf ? [Sr Tromcat Estate] 40 6700 Dauchamp, Nelly 5 150 Desmarinier, A.F. 7 900 Darcham (Durham), Estate 98 15775 Emerton (Everton), Estate 53 8650 E…all Estate 90 28000 1090 Gordwill (Goodwill), Estate 148 224000 5025 9125 G…aung Robert 132 17160 Guichard, Veuve 8 1425 Giaudel, Cesar 7 250 Sranville ? Ches ?. 22 900 200 Gruaud (Guaud) , J.F.+ R. 41 1800 366 Giaudel (Guaudel), L.J. (S) 5 600 (Hall ???) 59 5300 page 1 Généalogie et Histoire de la Caraïbe Parish of St.George = Roseau Estates N° of Slaves Sugar (lbs) Rum (gal.) Molasses (gal.) Coffee (lbs) Broughtt Forward 1045 319500 9615 11825 78341 Letang, J.B.P. -

Population and Housing Census 2011 (Preliminary Results)

Commonwealth of Dominica 2011 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS PRELIMINARY RESULTS CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE MINISTRY OF FINANCE KENNEDY AVENUE ROSEAU SEPTEMBER 2011 CENSUS 2011 - Preliminary Results Table of Contents Page Introduction 3 Explanatory Notes 4 Review 6 Table 1 Review of Demographic Data 1991 to 2010 9 Table 2 Population Trends - Census 1871 to 2011 9 Table 3 Population and Sex Ratio by Parish- 2011 10 Table 4 Non-institutional Population and Percentage Change by Parish - Censuses 1981 - 2011 11 Table 5 Non-institutional Population Distribution and Density by Parish Censuses 1991 - 2011 12 Table 6 Non-institutional and Institutional Population by Parish - 2011 13 " Table 7 Non-institutional Population by Geographic Area 1991- 2011 14 Table 8 Non-institutional Population, Households and Dwelling Units by Geographic Area. 19 Table 9 Non-institutional Population, Households and Type of Dwelling Units by Geographic Area. 23 Table 9.1 Non-institutional Population, Households and Dwelling Units 26 Chart 1 Non-Institutional Population Census 1871-Census -2011 27 Chart 2 Non-Institutional Population by sex and Census years 1981-2011 27 2 CENSUS 2011 - Preliminary Results INTRODUCTION The preliminary results of Census 2011 was extracted from the Census Visitation Records. It must therefore be emphasized that this information is based on preliminary findings from the May 2011 Dominica Population and Housing Census. It is not final information and is subject to slight changes after processing of final Census data. This report also includes census data from 1981 and other demographic trends over the last ten years. The Central Statistical Office acknowledges the assistance and cooperation of individuals groups, institutions, and government departments in making this Census successful. -

Commonwealth of Dominica Office of Director of Audit Report of The

Commonwealth of Dominica Office of Director of Audit Report of the DIRECTOR OF AUDIT on the AUDIT OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS For the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 2013 CONTENTS Letter………………………………………………………..……………… 1 Certificate of the Director of Audit ……………………………………… 2 Statement of Assets and Liabilities…………………………………….. 3 Statement of External Debt ……………………………………… 4 Annual Abstract Account of Receipts and Payments ………………... 6 Notes to the Financial Statements……………………………………… 9 CHAPTER 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………... 19 Audit Mandate ……………………………………………………………. 19 Audit Approach……………………………………………………………. 21 Submission of Accounts………………………………………………….. 23 Reporting Process and Practices ………………… ……………………. 23 Smart Stream System……………………………………………………. 23 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………….. 23 CHAPTER 2 Annual Abstract Account of Revenue and Expenditure Revenue………………………………………………………........ 24 Expenditure………………………………………………………… 30 Statement of Public Debt………………………………………………..... 34 1 CHAPTER 3 Contingencies Fund Advance Warrant……………………………….. 35 Travel Advances ………….………………………………………………. 36 Virement Warrants………………………………………………………… 37 Dishonoured Cheques ………………………………………………….. 37 Arrears of Revenue ……………………………………………............... 38 Overtime……………………………………………………………………. 39 CHAPTER 4 Government Capital Projects……………………………………………… 40 CHAPTER 5 Special Audits………………………………………………………………. 61 END 2 OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF AUDIT TREASURY BUILDING ROSEAU COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA August 26, 2016 The Honourable Minister for Finance Financial Complex Roseau COMMONWEALTH -

Mapaction Brochure

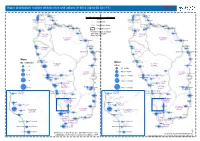

Potable water status: Litres delivered in last five days and remaining days supplies Up to 8 October 2017 Potable Water status: litres delivered in last 5 days and remaining days supplies (up to 08 Oct 2017) All settlements within an 'Operational' Water Dominica 0 2.5 5 10 15 MA626 v1 Capuchin Penville Capuchin Service Area are removed from this representation L'Autre Clifton Bord Kilometers as their demands 'should' be being met. In 2017, Hurricanes Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille !( Settlements Calculation of water remaining based on the Toucari & Morne Cabrit Case population x 7.5 litres per person per day Irma and Maria Savanne Paille Savanne Paille & Tantan & Tantan Moore Park Thibaud Major/Minor Road Thibaud devastated parts of Estate Moore Park Estate Calibishie Anse de Mai Bense Parish Boundaries Bense & Hampstead the Caribbean. Dos & Hampstead Woodford Dos D'Ane Lagon & De D'Ane Hill Woodford Hill La Rosine Borne Borne MapAction Portsmouth Glanvillia Wesley Wesley ST. JOHN responded quickly ST. JOHN Picard 6561 PPL and in numbers, 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW producing hundreds Marigot & 9471 PPL 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord of maps, including Concord this one showing the Atkinson Dublanc & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka urgent need for water Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka in Dominica, which 1430 PPL Water (Days) ST. PETER 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku took a direct hit from St. Cyr Remaining days St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Category 5 Hurricane Gaulette (! < 1 day Gaulette Maria. MapAction Sineku (! 1 - 2 days Sineku volunteers were Coulibistrie Coulibistrie (! 2 - 3 days Morne Rachette amongst the first ST. -

Dominica Flash Appeal 2017

FLASH 2017 APPEAL HURRICANE MARIA SEPTEMBER TO DECEMBER 2017 DOMINICA Photo: OCHA/Audrey Janvier TOTAL POPULATION PEOPLE PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED REQUIREMENTS OF DOMINICA AFFECTED (US$) 71K 71K 65K 65K 31.1M Portsmouth SAINT JOHN SAINT ANDREW Marigot Populated areas SAINT PETER Anguilla 6 Sep, 06:00 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA Barbuda 6 Sep, 00:00 Saint Kitts Nevis Antigua SAINT JOSEPH Grande-Terre SAINT DAVID Basse-Terre Guadeloupe H urr ican e M Marie-Galante ari a t rac k DOMINICA 18 Sep 18:00 Roseau SAINT PAUL Detailed map k HurricaneHurricane IrMariama trac gust footprints SAINT GEORGE Roseau 18 Sep, 06:01800 mph SAINT PATRICK Martinique Hurrica ne Ma Castries 170 ria t rack BARBADOS 160 17 Sep, 12:00 SAINT Bridgetow150n LUKE 140 SAINT 130 MARK TRINIDAD AN120D TOBAGO 110 100 90 DOMINICA FLASH APPEAL 2017 DOMINICA SITUATION OVERVIEW On 18 September, Hurricane Maria evolved from a category cent in Portsmouth (St. John Parish), 70 per cent in South 1 storm to a category 5 storm in less than 18 hours, just Roseau (St. George Parish) and 70 per cent in Pointe Michel before it slammed the Caribbean island of Dominica (Source: (St. Luke Parish). Copernicus, the European satellite-mapping NASA). It thrashed the country with extreme winds and rain system, suggests that approximately 25 per cent of buildings and destroyed all in its path. At the time of landfall, sustained in St. Paul Parish (15 per cent in Roseau only) and 61 per cent winds, which were reported to be 260 km/h, affected the in St. -

Demographic Statistics No.5

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA DE,MOGRAP'HIC STAT~STICS NO.5 2008 ICENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE, Ministry of Finance and Social Security, Roseau, Dominica. Il --- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1 Analysis ll-Xlll Explanatory Notes XIV Map (Population Zones) XV Map (Topography) xvi TABLES Non-Institutional Population at Census Dates (1901 - 2001) 1 2 Non-Institutional Population, Births and Deaths by Sex At Census Years (1960 - 200I) 2 3 Non-Institutional Population by Sex and Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981,1991, and 2001) 3 4 Non-Institutional Population By Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981, 1991 and 2001) 4 5 Population By Parishes (1946 - 200 I) 5 6 Population Percentage Change and Intercensal Annual Rate of Change (1881 - 200 I) 6 7 Population Density By Land Area - 200I Census compared to 1991 Census 7 8 Births and Deaths by Sex (1990 - 2006) 8 9 Total Population Analysed by Births, Deaths and Net Migration (1990 - 2006) 9 10 Total Persons Moving into and out ofthe Population (1981 -1990, 1991 - 2000 and 2001 - 2005) 10 II Number ofVisas issued to Dominicans for entry into the United States of America and the French Territories (1993 - 2003) 11 12 Mean Population and Vital Rates (1992 - 2006) 12 13 Total Births by Sex and Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 13 14 Total Births by Sex and Health Districts (1996 - 2006) 14 15 Total Births by Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 15 15A Age Specific Fertility Rates ofFemale Population 15 ~ 44 Years not Attending School 1981. 1991 and 2001 Census 16 16 Age Specific Birth Rates (2002 - 2006) 17 17 Basic Demographic -

Correlating Monotonous Crystal-Rich Dacitic Ignimbrites in Dominica: the Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite Alexandra Flake Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2014 Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite Alexandra Flake Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Geophysics and Seismology Commons, and the Volcanology Commons Recommended Citation Flake, Alexandra, "Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite" (2014). Honors Theses. 519. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/519 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Correlating monotonous crystal-rich dacitic ignimbrites in Dominica: The Layou and Roseau Ignimbrite ----------------------------------------------------------- by Alexandra Flake Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Department of Geology UNION COLLEGE June 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Holli Frey for her guidance, support and wisdom throughout this entire process. She has taught me an incredible amount over the course of this thesis and most importantly has helped me grow as a student, scientist, and individual in and outside of the classroom. It was an amazing opportunity to work with her and made this thesis an incredibly rewarding experience. I would also like to thank Matthew Manon for running the ICP-MS, SEM and helping me throughout summer research, Bill Neubeck for making my sample thin sections, Deborah Klein for helping organize both trips down to Dominica, David Gillikin for inspiring me to become a geology major, and finally, the Union College Geology Department for financially supporting my multiple trips to Dominica to make this thesis possible. -

DOMINICA: PRIMARY and SECONDARY SCHOOL ATTENDANCE RATES (For the Week of 27 November 2017)

DOMINICA: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOL ATTENDANCE RATES (for the week of 27 November 2017) Western Primary Eastern Primary Northern Primary Southern Primary Penville Attendance Attendance Attendance Attendance Clifton Rate Rate Rate Rate Baroness Patrica Scotland Primary Savane Paille Thibaud Paix Bouche Calibishie Primary Bense Primary Portsmouth Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill 55% Roosevelt Douglas St. John's 80% 67% 72% Temple SDA Dominica SDA Wesley St. John North East Comprehensive St. Andrew W.S.Stevens *75% of schools are *77% of schools are *88% of schools are *83% of schools are Concorde open for all students open for all students open for all students open for all students Dublanc Atkinson Lighthouse Primary Western Secondary Eastern Secondary Northern Secondary Southern Secondary St. Peter Attendance Attendance Attendance Attendance Salybia Rate Rate Rate Rate Colihaut Sineku Coulibistrie Castle Bruce St. Joseph 57% Castle Bruce 51% Salisbury 98% 99% Belles Kelleb John Laurent Primary St. David St. Joseph SDA *67% of schools are *Both schools are San Sauveur *67% of schools are *The single school is Isaiah Thomas open for all students only open for grades 4 & 5 open for all students open for all students Warner Campbell North East Comprehensive Mahaut Grand Fond St. Paul Morne Jaune )" Eastern Primary (13) Massacre Pioneer Preparatory School ") Northern Primary (16) Jones Beaupierre Primary School Roseau Inset Trafalgar Wotten Waven ") Southern Primary (12) Christian Goodwill Union Morne Prosper ") Primary ") School St. George Goodwill !( ") Western Primary (16) ") Petite Roseau Savane ") Berean Giraudel Delices (! Dominica Academy Eastern Secondary (2) Orion Grammar !(Convent St. Patrick Academy Roseau Convent Preparatory Primary High School (! Bellevue Chopin Northern Secondary (3) Dominica ")") Ro!(s")eau Community ") !(SDA St. -

NAMES on DOMINICA Dominica Was Occupied Successively by Speakers

NAMES ON DOMINICA BY DOUGLAS TAYLOR *) Dominica was occupied successively by speakers of Arawakan, Cariban, French, and English dialects, all of which have left their mark in place-names, as well as in the names of local flora and fauna. African influence appears to have been minimal in this respect. The Arawakan language of the island's early in- habitants survived that of the Carib invaders (from which, how- ever, many words were borrowed), but the last native speaker died about 1920. Two languages are spoken today: English and a dialect of French Creole. The former, being the language of prestige, is usually employed by the more socio-economically privileged minority, the latter by the peasant majority, few of whom know much English. However, members of the first class often resort to Creole in their more intimate relations; while many among even the poorest peasants may be heard addressing young children in what they believe to be English, and chiding them for speaking "Patois". One curious result of this situation is that not only local fruits, trees, fishes, birds, e/c., but also many places — probably most of those that have ever been recorded in writing — have two (or more) names, the one em- ployed in Creole and the other in English speech. So, for example, Grande Anse or Portsmouth is the island's second largest town, Charlotteville or New Town is a suburb of the capital Roseau (which has no other name), Cachacrou or Scots Head is a peninsula at the island's southwestern extremity, Cachibona of Clyde is one of its rivers. -

Socio-Economic Monitoring Assessment of Coastal Management in the Colihaut, Dublanc and Bioche Villages of Dominica

Socio-economic monitoring assessment of coastal management in the Colihaut, Dublanc and Bioche villages of Dominica ALTHIA ST. LOUIS, DERRICK THEOPHILE, JULLAN DEFOE, RHIANNAN PRICE AND ROSETTE LEWIS Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES) University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences Cave Hill Campus, Barbados 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Coastal management has justifiably become a priority throughout the world. The ecological and economic value of coastlines, reefs, beaches, fisheries, and marine life cannot be underestimated as the steady degradation of natural resources prevails worldwide. To avoid complete loss of such resources, decisions that impact the fragile coastal ecosystem must be carefully determined by the gamut of stakeholders. Sustainable development has delineated guidelines for improved management, but the process to sustainability is thwarted by a lack of information and conflicting stakeholder agendas. An inherent lack of information makes socio-economic monitoring an important key in determining the most effective management strategies. Accounting for social, cultural, and economic influences strengthens the decision-making process by giving it a more accurate, holistic approach. Often, these influences are remembered only as they are passed down generation to generation, and subsequently, this anthropological information can be lost as values and traditions shift or change over time. The strength of the socio-economic assessment is the preservation of these important social and cultural values, not in isolation, but in tandem with equally significant factors such as economics and scientific data. The purpose of this study is to preserve a social, cultural, and economic portrait of three coastal communities so that existing and future scientific data can be useful for their sustainable development. -

Water Distribution: Number of Deliveries and Volume in Litres (Up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 V2

Water distribution: number of deliveries and volume in litres (up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 v2 CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford Penville 0 1.5 3 6 9 12 Penville Clifton L'Autre Bord Clifton L'Autre Bord Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Kilometers Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Toucari & Morne Cabrit !( Toucari & Morne Cabrit Savanne Paille & Tantan Settlements Savanne Paille & Tantan Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Major/Minor Road Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Parish Boundaries Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Portsmouth Portsmouth Population figure displayed Glanvillia Wesley Glanvillia Wesley ST. JOHN after Settlement and ST. JOHN Picard Picard 6561 PPL Parish Names 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka 1430 PPL ST. PETER Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku St. Cyr St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Gaulette Gaulette Sineku Sineku Water Coulibistrie Coulibistrie Morne Rachette Water Morne Rachette No. deliveries ST. JOSEPH ST. JOSEPH 5637 PPL Castle Bruce Litres Castle Bruce 1 - 2 Salisbury Salisbury 5637 PPL 13 - 8000 3 - 4 Belles Belles ST. DAVID 8001 - 16000 ST. DAVID 6043G PooPdL Hope & Dix Pais & Tranto 6043G PooPd LHope & Dix Pais & Tranto 5 - 6 St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area San Sauveur 16001 - 24000 San Sauveur Layou Village Layou Village Warner Petite Soufriere Warner Petite Soufriere Tarou Tarou 7 - 8 Pond Casse 24001 - 32000 Pond Casse Campbell & Bon Repos Campbell & Bon Repos Jimmit Jimmit Mahaut ST.