Three Essays on the Macroeconomic Impact of Inflation Targeting Najib

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Institutions and Global Forces: Norwegian Wage Formation Since Industrialisation †

econometrics Article Between Institutions and Global Forces: Norwegian Wage Formation Since Industrialisation † Ragnar Nymoen 1,2 1 Department of Economics, University of Oslo, POB 1095 0317 Oslo, Norway; [email protected]; Tel.: +47-22-855-148 2 Centre for Wage Formation at Economic Analysis, POB 0650, Oslo, Norway † Paper presented at the workshop Macroeconomics and Policy Making, arranged in honour of Asbjørn Rødseth, 18 May, 2016, by the Department of Economics, University of Oslo. Thanks to Olav Bjerkholt for comments, and for showing me the article written by Frisch about “rational wage policies”, and the correspondence with Haavelmo that it led to. Discussions at the Workshop in econometrics at Statistics Norway, 21 October 2016, were also very useful, thanks to the participants. Thanks also to Jan Morten Dyrstad, David F. Hendry , Steinar Holden, Tord S. Krogh and Mikkel Myhre Walbækken for important comments and suggestions. Finally, thanks to the editors and to two anonymous referees for their comments, both critical and constructive. The numerical results in this paper were obtained by the use of OxMetrics 7/PcGive 14 and Eviews 9.5. Academic Editors: Gilles Dufrénot, Fredj Jawadi and Alexander Mihailov Received: 31 August 2016; Accepted: 13 December 2016; Published: 12 January 2017 Abstract: This paper reviews the development of labour market institutions in Norway, shows how labour market regulation has been related to the macroeconomic development, and presents dynamic econometric models of nominal and real wages. Single equation and multi-equation models are reported. The econometric modelling uses a new data set with historical time series of wages and prices, unemployment and labour productivity. -

The Role of the History of Economic Thought in Modern Macroeconomics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Laidler, David Working Paper The role of the history of economic thought in modern macroeconomics Research Report, No. 2001-6 Provided in Cooperation with: Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario Suggested Citation: Laidler, David (2001) : The role of the history of economic thought in modern macroeconomics, Research Report, No. 2001-6, The University of Western Ontario, Department of Economics, London (Ontario) This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/70392 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Role of the History of Economic Thought in Modern Macroeconomics* by David Laidler Bank of Montreal Professor, University of Western Ontario Abstract: Most “leading” economics departments no longer teach the History of Economic Thought. -

ECONOMICS of the FREE SOCIETY By

ECONOMICS OF THE FREE SOCIETY by WILHELM RÖPKE Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies—Geneva Translated by PATRICK M. BOARMAN HENRY REGNERY COMPANY Chicago, 1963 The assistance o£ the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists, Philadelphia, in the publication of this book is gratefully acknowledged. First Published in Austria in 1937 Die Lehre von der Wirtschaft (Julius Springer, Vienna) Translated from the 9th German Edition Published in Switzerland in 1961 by Eugen-Rentsch Verlag Erlenbach-Zurich Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 63-10948 COPYRIGHT © 1963 BY HENRY REGNERY COMPANY, CHICAGO 4, ILLINOIS Manufactured in the United States of America DISTURBANCES OF ECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM 221 3. The Impact of Keynesianism John Maynard Keynes, who died in 1946 at the age of 62, is not only the best known economist o£ our times but also a man who by any standards must be reckoned as one of the leading personages of the first half of the twentieth century. The history of the era which followed World War I can no more dispense with the name of this singular individual than it can with the names of Einstein, Churchill, Roosevelt, or Hitler. It is only in this broad perspective that Keynes' full importance becomes visible. How ought we to judge the in- fluence of this man? Is he the Copernicus of economics, as so many claim, the man who banished the ghosts of economics grown rigid in the chains of tradition, who opened the door to prosperity and stability? Or did he destroy more than he created and has he sum- moned into being spirits that today he possibly would be gladly rid of? It is difficult to make a simple answer to these questions. -

Two Views of Monetary Policy: the Attwood-Mill Debate Revisited

Thomas M. Humphrey price stability is an essential prerequisite for an effi- ciently functioning economy and a sustained high average level of employment, (2) recommends that the monetary authority gracluaily approach and there- after permanently adhere to a target path of money are again in full en~plojwenf at ample mages. growth consistent with a zero rate of inflation, (3) THOW% ATTWOOD (1819) prescribes that discretionary fine-tuning be replaced by fixed monetary rules, in particular the noninfla- Mr. Attwood opines, that the multiplication of tionary constant money growth rate rule, and (4j the circulating p>zedEClizlm,and the consequent di- warns that the social cost of accepting inherited n&&ion of its value, do not wzerely ditninislz the inflation far exceeds the cost of eradicating it. pressure of taxes and debts, and other fixed The debate between policy activists and stable charges, but give en@oy+newt to labor, and fhaf money proponents is not new. The essentials of the to an indefinite extent . Mr. Attwood’s debate can be traced back more than 140 years to a error is that of supposing that a depreciation of celebrated controversy between Thomas Attwood and the currency really increases the demand for all John Stuart Mill over gold versus paper monetary articles, and conseqztently their prodlrction, be- standards in post-Napoleonic war Britain. This cause, zcnder sogme circumstances, it nzay create debate occurred during a long deflationary period a false opinion of an increase of depnand; which that abruptly succeeded a wartime inflationary boom. false opinion leads, as tlze reality would do, to an The postwar deflation brought severe unemployment. -

Debasement and the Decline of Rome Kevin Butcher1

Debasement and the decline of Rome KEVIN BUTCHER1 On April 23, 1919, the London Daily Chronicle carried an article that claimed to contain notes of an interview with Lenin, conveyed by an anonymous visitor to Moscow.2 This explained how ‘the high priest of Bolshevism’ had a plan ‘for the annihilation of the power of money in this world.’ The plan was presented in a collection of quotations allegedly from Lenin’s own mouth: “Hundreds of thousands of rouble notes are being issued daily by our treasury. This is done, not in order to fill the coffers of the State with practically worthless paper, but with the deliberate intention of destroying the value of money as a means of payment … The simplest way to exterminate the very spirit of capitalism is therefore to flood the country with notes of a high face-value without financial guarantees of any sort. Already the hundred-rouble note is almost valueless in Russia. Soon even the simplest peasant will realise that it is only a scrap of paper … and the great illusion of the value and power of money, on which the capitalist state is based, will have been destroyed. This is the real reason why our presses are printing rouble bills day and night, without rest.” Whether Lenin really uttered these words is uncertain.3 What seems certain, however, is that the real reason the Russian presses were printing money was not to destroy the very concept of money. It was to finance their war against their political opponents. The reality was that the Bolsheviks had carelessly created the conditions for hyperinflation. -

The Causes of the Economic Crisis

THE CAUSES OF THE ECONOMIC CRISIS AND OTHER ESSAYS BEFORE AND AFTER THE GREAT DEPRESSION LUDWIG VON MISES The Ludwig von Mises Institute dedicates this volume to all of its generous donors and wishes to thank these Patrons, in particular: Reed W. Mower ~ Hugh E. Ledbetter; MAN Financial Australia; Roger Milliken; E.H. Morse ~ Andreas Acavalos; Toby O. Baxendale; Michael Belkin; Richard B. Bleiberg; John Hamilton Bolstad; Mr. and Mrs. J.R. Bost; Mary E. Braum; Kerry E. Cutter; Serge Danilov; Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy S. Davis; Capt. and Mrs. Maino des Granges; Dr. and Mrs. George G. Eddy; Reza Ektefaie; Douglas E. French and Deanna Forbush; James W. Frevert; Brian J. Gladish; Charles Groff; Gulcin Imre; Richard J. Kossmann, M.D.; Hunter Lewis; Arthur L. Loeb; Mr. and Mrs. William W. Massey, Jr.; John Scott McGregor; Joseph Edward Paul Melville; Roy G. Michell; Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Miller; Mr. and Mrs. R. Nelson Nash; Thorsten Polleit; Mr. and Mrs. Donald Mosby Rembert, Sr.; top dog™; James M. Rodney; Sheldon Rose; Mr. and Mrs. Joseph P. Schirrick; Mr. and Mrs. Charles R. Sebrell; Raleigh L. Shaklee; Tibor Silber; Andrew Slain; Geoffry Smith; Dr. Tito Tettamanti; Mr. and Mrs. Reginald Thatcher; Mr. and Mrs. Loronzo H. Thomson; Jim W. Welch; Dr. Thomas L. Wenck; Mr. and Mrs. Walter Woodul, III; Arthur Yakubovsky ~ Mr. and Mrs. James W. Dodds; Francis M. Powers Jr., M.D.; James E. Tempesta, M.D.; Lawrence Van Someren, Sr.; Hugo C.A. Weber, Jr.; Edgar H. Williams; Brian Wilton THE CAUSES OF THE ECONOMIC CRISIS AND OTHER ESSAYS BEFORE AND AFTER THE GREAT DEPRESSION LUDWIG VON MISES Edited by Percy L. -

The Gold Standard, Deflation and Fascism in Polanyi's Great

The gold standard, deflation and fascism in Polanyi’s Great Transformation. A multidisciplinary analysis ERNESTO CLAR Introduction In 1944 Karl Polanyi published a work that would become a milestone in 20th-century social science, The Great Transformation. He was among the first to explain the economic and political catastrophe of the inter-war period as the final stage of a long-term process that reigned in Western Europe (and the United States) in the wake of the Napoleonic wars, market liberalism. Polanyi considered those ‘one hundred years’ to be a coherent period covering the rise and fall of 19th-century civilization. Polanyi characterized the 19th-century civilization that was destined to die with the Great Depression of the 20th century by four institutions: the balance-of-power system, the gold standard, the self-regulating market and the liberal state. Of these institutions, Polanyi asserts that the gold standard was the only one to survive both the Long Depression (previously known as the Great Depression) of 1873-1886 and the Great War. However, its ultimate failure delivered the death blow for market liberalism and, in some places, also swept liberal democracy away with it. The final part of Polanyi’s book gives a historical account of this process. However, early on in the book, Polanyi warns us that he is not conducting historical research: «what we are searching for is not a convincing sequence of outstanding events, but an explanation of their trend in terms of human institutions»1. This statement should be understood as a declaration of intent; Polanyi’s analysis was not limited to a single subject, such as history or economics, and he made this very clear by saying «we shall encroach upon the field of several disciplines in the pursuit of a single aim»2. -

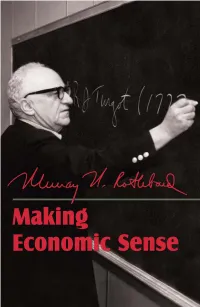

Making Economic Sense.Pdf

Making Economic Sense 2nd Edition Murray N. Rothbard Ludwig von Mises Institute AUBURN, ALABAMA Copyright © 1995, 2006 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832. ISBN: 0-945466-46-3 CONTENTS Preface by Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr. .xi Introduction to the Second Edition by Robert P. Murphy . .xiii MAKING ECONOMIC SENSE 1 Is It the “Economy, Stupid”? . .3 2 Ten Great Economic Myths . .7 3 Discussing the “Issues” . .19 4 Creative Economic Semantics . .23 5 Chaos Theory: Destroying Mathematical Economics From Within? . .25 6 Statistics: Destroyed From Within? . .28 7 The Consequences of Human Action: Intended or Unintended? . .31 8 The Interest Rate Question . .33 9 Are Savings Too Low? . .37 10 A Walk on the Supply Side . .40 11 Keynesian Myths . .43 12 Keynesianism Redux . .45 v vi Making Economic Sense THE SOCIALISM OF WELFARE 13 Economic Incentives and Welfare . .53 14 Welfare as We Don’t Know It . .56 15 The Infant Mortality “Crisis” . .58 16 The Homeless and the Hungry . .62 17 Rioting for Rage, Fun, and Profit . .64 18 The Social Security Swindle . .68 19 Roots of the Insurance Crisis . .71 20 Government Medical “Insurance” . .74 21 The Neocon Welfare State . .77 22 By Their Fruits . .81 23 The Politics of Famine . .84 24 Government vs. Natural Resources . .87 25 Environmentalists Clobber Texas . .89 26 Government and Hurricane Hugo: A Deadly Combination . -

Chicago Monetary Traditions

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Laidler, David Working Paper Chicago monetary traditions Research Report, No. 2003-3 Provided in Cooperation with: Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario Suggested Citation: Laidler, David (2003) : Chicago monetary traditions, Research Report, No. 2003-3, The University of Western Ontario, Department of Economics, London (Ontario) This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/70428 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Chicago Monetary Traditions by David Laidler (Bank of Montreal Professor) Abstract: This paper, prepared for the forthcoming Elgar Companion to the Chicago School of Economics (Ross Emmett and Malcolm Rutherford eds.) describes monetary economics as it existed in four eras at the University of Chicago. -

Development and Bretton Woods

CHAPTER 5 Development and Bretton Woods This chapter examines why the liberalization of currency transactions, and also (to some extent) of trade, was less effective outside the developed world, or why the idea of "one world" and of a single world economy was challenged. The IMF worked out a technical and analytical device for t e achievement of stabilization, the so-called Polak model, but its operation was limited by what was at that time usually described as a failure or absence of political will in member countries. The resulting difficulties and failures obliged the IMF and the World Bank to begin to rethink issues concerned with the design of the international order and their own role within it. The conference of Bretton Woods, held in the last phase of a great world war, had—perhaps not surprisingly—concerned itself only rather peripherally with development issues. Although Article I of the Fund's Articles of Agreement stated an objective of "the development of the productive re- sources of all members," development finance had not been a major concern in the circumstances of 1944. The conference had avoided any attempt to distinguish between groups of members, and its participants ruled out an additional phrase suggested by the Indian delegation as part of the second "purpose of the Fund" set out in that Article: "to assist in the fuller utilisation of the resources of economically under-developed countries "1 Indeed it only became clear later that there was a specific problem about "development." It was only in the course of the first postwar decades that the "developing world" began to define itself politically and economically. -

Nber Working Paper Series War and Inflation in The

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES WAR AND INFLATION IN THE UNITED STATES FROM THE REVOLUTION TO THE FIRST IRAQ WAR Hugh Rockoff Working Paper 21221 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21221 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2015 This paper was prepared for a conference to honor Mark Harrison, organized by Jari Eloranta and Bishnu Gupta, Warwick University, March 31-April 1, 2014. An early draft was presented at a workshop on the Costs and Consequences of War, organized by Sarah Kreps, Cornell University, April 2013. On that occasion I benefitted from the comments of my discussant Jonathan Kirshner. Farley Grubb helped me understand monetary developments during the Revolutionary War. Nga Nguyen and Jessica Scheld provided able research assistance. I am solely responsible for the remaining errors. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Hugh Rockoff. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. War and Inflation in the United States from the Revolution to the First Iraq War Hugh Rockoff NBER Working Paper No. 21221 May 2015 JEL No. N10 ABSTRACT The institutional arrangements governing the creation of money in the United States have changed dramatically since the Revolution. -

America's Great Depression

America’s Great Depression Fifth Edition America’s Great Depression Fifth Edition Murray N. Rothbard MISES INSTITUTE Copyright © 1963, 1972 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Third Edition Copyright © 1975 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Fourth Edition Copyright © 1983 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Fifth Edition Copyright © 2000 by The Ludwig von Mises Institute Copyright © 2000 by The Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832. ISBN No.: 0-945466-05-6 TO JOEY, the indispensable framework The Ludwig von Mises Institute dedicates this volume to all of its generous donors, and in particular wishes to thank these Patrons: Dr. Gary G. Schlarbaum – George N. Gallagher (In Memoriam), Mary Jacob, Hugh E. Ledbetter – Mark M. Adamo, Lloyd Alaback, Robert Blumen, Philip G. Brumder, Anthony Deden (Sage Capital Management, Inc.), Mr. and Mrs. Willard Fischer, Larry R. Gies, Mr. and Mrs. W.R. Hogan, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. William W. Massey, Jr., Ellice McDonald, Jr., MBE, Rosa Hayward McDonald, MBE, Richard McInnis, Mr. and Mrs. Roger Milliken (Milliken and Company), James M. Rodney, Sheldon Rose, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Schoppe, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Urie, Dr. Thomas L. Wenck – Algernon Land Co., L.L.C., J. Terry Anderson (Anderson Chemical Company), G. Douglas Collins, Jr., George Crispin, Lee A.