Developing a Set of Indicators to Identify, Monitor, and Track Impacts and Change in Forests of the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

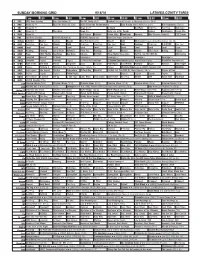

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Waves Apart •Hollywood Q&A Page14

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 18, 2017 8:07:23 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of November 26 - December 2, 2017 Gustaf Skarsgård stars in “Vikings” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 Waves apart •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The sons of Ragnar are at war, putting the gains of their father into jeopardy as the unity of the Vikings is fractured. With Floki (Gustaf Skarsgård, “Kon-Tiki,” 2012) now letting the gods guide him, and Lagertha (Katheryn Winnick, “The Dark Tower,” 2017) dealing with civil unrest and a looming prophecy, it’s understandable why fans are anxious with anticipation for the season 5 premiere of “Vikings,” airing Wednesday, Nov. 29, on History Channel. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALES Motorsports& SERVICE IT’S MOLD ALLERGY SEASON 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Are you suffering from itchy eyes, sneezing, sinusitis We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC or asthma?Alleviate your mold allergies this season. Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. -

Biscayne Avenue, Canary Wharf, London, Greater London. E14 9QT £1,200 Monthly *

Biscayne Avenue, Canary Wharf, London, Greater London. E14 9QT £1,200 Monthly * • MODERN STUDIO APARTMENT • IMPRESSIVE POSTCODE • ULTRA MODERN FITTED KITCHEN • FULLY INTEGRAL APPLIANCES • OPEN PLAN KITCHEN • MODERN SHOWER ROOM • AVAILABLE 13TH June • MINUTES FROM CANARY WHARF TOWER • EARLY VIEWING RECOMMENDED Ref: PRC11769 Viewing Instructions: Strictly By Appointment Only General Description Victor Michael are delighted to present this trendy little gem to the rental market. Located just a stones throw from Canary Wharf, this property is guaranteed to please. The apartment boasts a balcony located directly from the reception room, ideal for those summer evenings. The kitchen is open plan to the lounge and boasts fully integral appliances. The shower room is ultra modern and comes fully tiled. Call Victor Michael on 0207 540 9696 Bus Routes 15 D6 D7 N550 Schools Colloden Primary School LOCATION; Whether you want to relax and enjoy a leisurely brunch at the weekend, enjoy after-work drinks, find fine dining à deux, try the finest whiskies while soaking up the smooth sounds of jazz, or experience the soul of Mexico in the heart of the city, Canary Wharf has gathered the very best from around the world for you to enjoy. A beautiful and modern part of London, Canary Wharf's iconic skyline is an integral part of the landscape, with the addition of Crossrail Place, the latest shopping and leisure destination offering new restaurants, a cinema, plus one of London's biggest roof gardens. Combined with a fantastic programme of music, film, theatre, dance, art, fashion and more throughout the year, plus over 300 shops, cafes, bars and restaurants, there has never been a better time to visit Canary Wharf. -

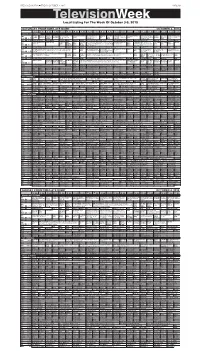

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of October 3-9, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of October 3-9, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT OCTOBER 3, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel “Red The Lawrence Welk Doc Martin Martin Keeping As Time Father Brown A for- No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Under- Sun Stu- Globe Trekker Park PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Rocks Homecom- Show finds out Louisa is Up Goes mer POW is suspected mum Å Hall of Fame Induction ground dio Ses- Güell; Casa Batlló. Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden ing” Å pregnant. Å By Å of murder. Ceremony. (N) sions (DVS) KTIV $ 4 $ Action Sports (N) Horse Racing Preview News News 4 Insider ›› “Live From New York!” (2015) Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Action Sports (N) (In Horse Racing Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big ›› “Live From New York!” (2015) Premiere. Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live (Season The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Stereo) Å gram Nightly News Bang Exploring the 40-year history of “Saturday Night (In Stereo) Å News Premiere) Miley Cyrus hosts and sons sons News Å KDLT % 5 % News (N) (N) Å Theory Live.” (In Stereo) (N) Å performs. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode). -

Post-Implementation Review of IFRS 10 IFRS 11 and IFRS 12

Mr. Hans Hoogervorst Chairman International Accounting Standards Board 7 Westferry Circus Canary Wharf London E14 4HD 21 May 2021 Dear Mr Hoogervorst Following the UK’s exit from the European Union, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has set up the UK Endorsement Board (UKEB) to fulfil statutory functions of influencing the development and subsequent adoption of International Accounting Standards for use in the UK. The UKEB secretariat has begun influencing activities in preparation for the delegation of those statutory functions to the UKEB. This letter forms part of those influencing activities and is intended to contribute to the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB) due process. The views expressed by the UKEB secretariat in this letter are separate from, and will not necessarily affect the conclusions in, any endorsement and adoption assessment on new or amended International Accounting Standards to be provided to the Secretary of State or the UKEB, once powers have been delegated. The UKEB secretariat welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the IASB’s post- implementation review of IFRS 10, IFRS 11 and IFRS 12 (the Standards). To develop our response, we have gathered evidence from stakeholder roundtables and interviews, desk- based reviews of annual reports from a sample of UK listed companies, and public consultation on our draft response. Our conclusions and recommendations in response to the IASB’s consultation are outlined below. For detailed responses to the questions in the IASB’s Request for Information (RFI) please see Appendix 1. Our overarching conclusion is that the Standards have achieved their objectives by introducing a principles-based approach to accounting for consolidation and joint arrangements and replacing the rules-based approach of earlier standards. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Back at 'Last'

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:34 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of March 5 - 11, 2016 Some of the cast of “The Last Man on Earth” Back at HMA.HMA. .Car .Care . Systems . ‘Last’ WASH WINTER AWAY HMA Car Care AT1 x 5 HMA. 978.744.4444 Superb polishing, interiors, great body work and more. 24/7 Car Wash HMACARCARE.COM 72 North St. (Rte. 114), Salem, MA Newspaper Advertising Works! Massachusetts’ First Credit Union THIS Located at 370 HighlandSt. Avenue, Jean's Salem Credit Union AD SPOTET Filler 3 x 3 COULD1 BE x YOURS. 3 Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Ask us about very economical advertising in Saturday’s Salem News TV Spotlight Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs (with an option to print a deeply ) discounted ad in The Salem News Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Contact: Glenda Duchesneau 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com 978-338-2540 • [email protected] Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere Federally Insured by NCUA FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:36 PM 2 • Salem News • March 5 - 11, 2016 Where there’s a Will Video Will Forte’s post-apocalyptic comedy returns from hiatus releases By Jacqueline Spendlove scouring the continent for other sur- nale to seven — plus Phil’s es- With the emergence of new char- companion worms die off one by TV Media vivors of a virus that has wiped out tranged astronaut brother, Mike (Ja- acters being more of a season 1 fo- one, but just as he’s about to com- most of humanity, and just after giv- son Sudeikis, “We’re the Millers,” cus, the first half of the current sea- mit suicide by jettisoning himself hristmas break and then ing up, he meets the good-hearted 2013), who’s stranded out in space, son has followed the group as it into space, he spots a newborn some! It’s been almost three (albeit profoundly irritating) Carol unbeknownst to anyone. -

Stacey Hinnen SAG-AFTRA

Stacey Hinnen SAG-AFTRA TELEVISION HOUSE OF LIES Recurring Showtime/Helen Hunt NCIS: Los Angeles “Unspoken” Guest Star CBS/Diana Valentine NCIS “Canary” Guest Star CBS/Terrence O’Hara CRIMINAL MINDS “Big Sea” Guest Star CBS/Glenn Kershaw ZEKE AND LUTHER “Super Shredder” Guest Star Disney XD/John Putch COLD CASE “One Fall” Guest Star CBS/Don Thorin MODERN FAMILY “Fizbo” Guest Star ABC/Jason Winer MY NAME IS EARL “Witch Lady” Guest Star NBC/Eyal Gordin ANGIE TRIBECA “Murder in the First Class” Co-Star TBS/Richie Keen WITHOUT A TRACE “The Stranger” Co-Star CBS/Armand Mastroianni SCRUBS “Her Story II” Co-Star Mastroianni ABC/Chris Koch GREY’S ANATOMY “The First Cut is the Deepest” Co-Star ABC/Peter Horton MONK “Mr. Monk Gets a New Shrink” Co-Star USA/Andrei Belgrader ER “The Show Must Go On” Co-Star NBC/John Wells THE CLASS “The Class Goes Trick or Treating” Co-Star CBS/James Burrows STUDIO 60 ON THE SUNSET STRIP “The Wrap Party” Co-Star NBC/David Semel THAT GUY “Pilot” Co-Star Fox/Betty Thomas THE O.C. “The Road Warrior” Co-Star Fox/Mike Fresco THE INSIDE “New Girl in Town” Co-Star Fox/Tim Minear BOSTON PUBLIC “Chapter 71” Co-Star Fox/Joe Napolitano FILM (partial) CALL TO HEROES Lead Eleven Three Prods THE PASSING Lead Eleven Three Prods DONATION Lead Bruton Stroube THE RIG Lead Anchor Bay Ent MONIKA Supporting Anchor Bay Ent RHINO Supporting Seno Reality Pics FATHER VS SON Supporting Film Crewe Prods SHARPSHOOTER Supporting Spike TV V.O. -

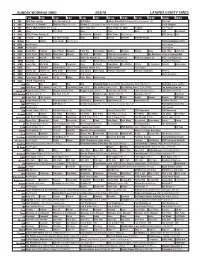

Sunday Morning Grid 2/25/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/25/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey St. Louis Blues at Nashville Predators. (N) Å 2018 Olympics 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Weird DIY Sci NASCAR NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Formosa Betrayed (2009) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Pavlo Live in Kastoria Å Joe Bonamassa Live at Carnegie Hall 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Mac Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K.