SMSS Conference Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFSA Cast in Steel Competition Bowie Knife Final Report Team Texas

SFSA Cast in Steel Competition Bowie Knife Final Report Team Texas State 3 Joshua Avery Ethan De La Torre Gage Dillon Advised by: Luis Trueba Engineering Technology Texas State University June 12, 2020 1 | P a g e Table of Contents ABSTRACT 3 1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Project Management 3 1.2 Literature Review 4 2. DESIGN 5 2.1 Design Selection 5 2.2 Alloy Selection 5 2.3 Production Selection 5 3. MANUFACTURABILITY 6 3.1 Design Analysis 6 3.2 Final Design 8 3.3 Production 10 4. QUALITY & PERFORMANCE 13 5. CONCLUSION 14 6. WORKS CITED 15 2 | P a g e ABSTRACT In the early 19th century, James Black created a different kind of knife for Jim Bowie. This knife was longer in length than the average knife and compared more to a mini sword. While the exact design and characteristics of the original Bowie knife was lost with James Black, the stories of the weapon captivated people. Our project was to capture the same aura surrounding the knife as James Black did many years ago but also commemorate the history associated with it. We created our Bowie knife model using Solidworks, cast it in IC440C Stainless Steel with the assistance of American Foundry Group, and polished it with our own tools. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Management Figure 1: Project Schedule Figure 1 shows the original Gantt chart for the Bowie Knife project. It began December 15th when we created the original proposition for the competition. Every period in the chat represents 1 week since the original 12/15 start date. -

Machete Fighting in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia

MEMORIAS Revista digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe colombiano Peinillas y participación popular: Pelea de machetes en Haiti, Cuba y Colombia 1 Peinillas and Popular Participation: Machete fighting in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia ∗ Dr. T. J. Desch-Obi Recibido: Agosto 27 de 2009 Aceptado: Noviembre 8 de 2009 RESUMEN: Este artículo explora la historia de esgrima con machetes entre los afro- descendientes en Haití, Cuba y Colombia. El machete, como un ícono sagrado de éxito individual y de guerra en África, se convierte para los esclavizados Africanos en una herramienta usada en la explotación de su trabajo. Ellos retuvieron la maestría en esta arma a través de la extensión del arte de pelea con palos. Esta maestría en las armas blancas ayudó a transformar el machete en un importante instrumento en las batallas nacionales de esas tres naciones. Aún en el comienzo del siglo veinte, el arte de esgrima con machetes fue una práctica social muy expandida entre los Afro-Caucanos, que les permitía demostrar su honor individual, como también hacer importantes contribuciones a las batallas nacionales, como la Colombo-Peruana. Aunque la historia publicada de las batallas nacionales realza la importancia de los líderes políticos y militares, los practicantes de estas formas de esgrima perpetuaron importantes contra- memorias que enfatizan el papel de soldados Afros quienes con su maestría con el machete pavimentaron el camino para la victoria nacional. PALABRAS CLAVES: Esgrima, afro-descendientes, machete. ABSTRACT: This article explores the history of fencing with machetes among people of African descent in Haiti, Cuba, and Colombia. The machete, a sacred icon of individual success and warfare in Africa, became for enslaved Africans a tool used in exploiting their labor. -

Outdoor& Collection

MAGNUM COLLECTION 2020 NEW OUTDOOR& COLLECTION SPRING | SUMMER 2020 early years. The CNC-milled handle picks up the shapes of the Magnum Collection 1995, while being clearly recognizable as a tactical knife, featuring Pohl‘s signature slit screws and deep finger choils. Dietmar Pohl skillfully combines old and new elements, sharing his individual shapes and lines with the collector. proudly displayed in showcases around the For the first time, we are using a solid world, offering a wide range of designs, spearpoint blade made from 5 mm thick quality materials and perfect craftsmanship. D2 in the Magnum Collection series, giving the knife the practical properties you can For the anniversary, we are very pleased that expect from a true utility knife. The knife we were able to partner once again with has a long ricasso, a pronounced fuller and Dietmar Pohl. It had been a long time since a ridged thumb rest. The combination of MAGNUM COLLECTION 2020 we had worked together. The passionate stonewash and satin finish makes the blade The Magnum Collection 2020 is special in designer and specialist for tactical knives scratch-resistant and improves its corrosion- many ways. We presented our first Magnum has designed more than 60 knives, among resistance as well. The solid full-tang build catalogue in 1990, followed three years later them the impressive Rambo Knife featured gives the Magnum Collection 2020 balance by the first model of the successful Magnum in the latest movie of the action franchise and stability, making it a reliable tool for any Collection series. This high-quality collector‘s with Sylvester Stallone. -

The Doolittle Family in America, 1856

TheDoolittlefamilyinAmerica WilliamFrederickDoolittle,LouiseS.Brown,MalissaR.Doolittle THE DOOLITTLE F AMILY IN A MERICA (PART I V.) YCOMPILED B WILLIAM F REDERICK DOOLITTLE, M. D. Sacred d ust of our forefathers, slumber in peace! Your g raves be the shrine to which patriots wend, And swear tireless vigilance never to cease Till f reedom's long struggle with tyranny end. :" ' :,. - -' ; ., :; .—Anon. 1804 Thb S avebs ft Wa1ts Pr1nt1ng Co., Cleveland Look w here we may, the wide earth o'er, Those l ighted faces smile no more. We t read the paths their feet have worn, We s it beneath their orchard trees, We h ear, like them, the hum of bees And rustle of the bladed corn ; We turn the pages that they read, Their w ritten words we linger o'er, But in the sun they cast no shade, No voice is heard, no sign is made, No s tep is on the conscious floor! Yet Love will dream and Faith will trust (Since He who knows our need is just,) That somehow, somewhere, meet we must. Alas for him who never sees The stars shine through his cypress-trees ! Who, hopeless, lays his dead away, \Tor looks to see the breaking day \cross the mournful marbles play ! >Vho hath not learned in hours of faith, The t ruth to flesh and sense unknown, That Life is ever lord of Death, ; #..;£jtfl Love" ca:1 -nt ver lose its own! V°vOl' THE D OOLITTLE FAMILY V.PART I SIXTH G ENERATION. The l ife given us by Nature is short, but the memory of a well-spent life is eternal. -

March 2008 Camillus (Kah-Mill-Us) the Way They Were by Hank Hansen

Camillus Knives Samurai Tales Are We There Yet? Shipping Your Knives Miss You Grinding Competition Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” March 2008 Camillus (Kah-mill-us) The Way They Were by Hank Hansen In recent months we have read about the last breaths of a fine old cutlery tangs. The elephant toenail pattern pictured has the early 3-line stamp on both company and its sad ending; but before this, Camillus was a great and exciting tangs along with the sword brand etch. Also the word CAMILLUS, in double firm that produced wonderful knives. When you look at some of the knives that outlined bold letters, was sometimes etched on the face of the master blade along they made in the past, some of them will certainly warm your hearts and make with the early 3-line tang marks. you wonder, why, why did I not appreciate the quality and beauty of these knives made in NewYorkState a long time ago. The different tang stamps used by Camillus, and the time period they were used, are wonderfully illustrated by John Goins in his Goins’Encyclopedia of Cutlery The Camillus Cutlery Co. was so named in 1902. It had its start some eight years Markings, available from Knife World. Other house brands that were used earlier when Charles E. Sherwood founded it on July 14, 1894, as the Sherwood include Camco, Catskill, Clover, Corning, Cornwall, Fairmount, Farragut, Cutlery Co., in Camillus, New York. The skilled workers at the plant had come Federal, High Carbon Steel, Mumbley Peg, Stainless Cutlery Co, Streamline, from England. -

Best of Steel Commando Ebook

BEST OF STEEL COMMANDO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank Pepper | 160 pages | 22 Aug 2019 | Rebellion | 9781781086810 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Best of Steel Commando PDF Book But we think Chris Reeve managed that with this monstrous fixed blade. Let's say you're out and about in a dress, walking the streets of NYC or getting on the subway. Fits most standard coolers. Heading to the gym? The blade is so sharp that you should warn anyone before you allow them to take a look at it. I'll need to see some follow through before I buy into a bottom here. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. These are specifically designed for defensive purposes, but they can definitely do some damage in close-quartered combat with another human. The classic ten eyelet boot, Commando is available on single, double and triple soles. Guaranteed for Life. Day 1. Line drawing of the original pattern of Fairbairn Sykes knife. The blade is constructed of high-strength stainless steel and this particular weapon includes a nylon sheath for safety in transport. Get our 2 Bumper carbon steel padlock. More From Gear. It might not look like much, but the VG blade and G10 handle make this a seriously durable and useful knife. However, it seems to get the job done while standing up to harsh conditions, and the innovations in design are truly unique. The resulting design was influenced by the knives that Fairbairn and Sykes had experimented with in Shanghai, as well as earlier designs produced by Wilkinson. -

Machete for the Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-118-02-04 on 1 January 1972. Downloaded from 97 SIXTY YEARS AG'O WE have noted many times how past problems keep cropping up time and again over the years. One such example is how the R.A.M.C. should be armed. This problem has produced many articles and letters one of which we reprint below as it shews such a practical and sensible approach. The letter's recommendations will awaken memories of the Peninsular War-the Rifle Bde were issued with sword bayonets for their Baker Rifles, but owing to a fault in design the bayonet bar or lug was placed too far forward on the rifle, and in con sequence the heavy brass guard of the sword bayonet received the full force of the dis charge and as a result the guard and hilt were soon distorted and the weapon made useless. The sword bayonets were not however withdrawn as they were invaluable as bill-hooks for cutting brushwood for huts and splitting wood for fires. MACHETE FOR THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS SIR.-On page 170, line 39, Royal Army Medical Corps Training, 1911, the following sentence occurs: "The tools required are a yard-measure, a tenon-saw or billhook, and a jack-knife." These are the tools required to adapt a Scotch haycart to the transport of Protected by copyright. wounded. It all looks beautifully simple and easy on paper when one imagines the yard measure, &c. ready to hand. In actual practice one would more easily find the haycart than the tools, and the probability is that one would have to adapt the article with the aid of a jack-knife only. -

Contract W52H09-06-D-0068 for M7 Bayonets

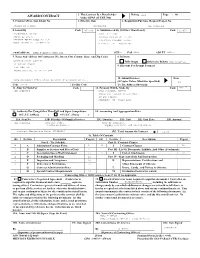

AWARD/CONTRACT 1. This Contract Is A Rated Order RatingDOA5 Page 1 Of 33 Under DPAS (15 CFR 700) 2. Contract (Proc. Inst. Ident) No. 3. Effective Date 4. Requisition/Purchase Request/Project No. W52H09-06-D-0068 2006MAY09 SEE SCHEDULE 5. Issued By CodeW52H09 6. Administered By (If Other Than Item 5) Code S3305A TACOM-ROCK ISLAND DCMA BUFFALO AMSTA-LC-CSC-C NIAGARA CENTER SUITE 340 BARBARA FOLEY (309)782-2547 130 SOUTH ELMWOOD AVENUE ROCK ISLAND IL 61299-7630 BUFFALO NY 14202-2392 e-mail address: [email protected] SCDB PASNONE ADP PT HQ0337 7. Name And Address Of Contractor (No. Street, City, County, State, And Zip Code) 8. Delivery ONTARIO KNIFE COMPANY FOB Origin X Other (See Below) SEE SCHEDULE 26 EMPIRE STREET 9. Discount For Prompt Payment P.O. BOX 145 FRANKLINVILLE, NY 14737-1099 10. Submit Invoices Item TYPE BUSINESS: Other Small Business Performing in U.S. (4 Copies Unless Otherwise Specified) 12 Code2V376 Facility Code To The Address Shown In: 11. Ship To/Mark For Code 12. Payment Will Be Made By Code HQ0337 SEE SCHEDULE DFAS COLUMBUS CENTER NORTH ENTITLEMENT OPERATIONS PO BOX 182266 COLUMBUS OH 43218-2266 13. Authority For Using Other Than Full And Open Competition: 14. Accounting And Appropriation Data 10 U.S.C. 2304(c)( ) 41 U.S.C. 253(c)( ) 15A. Item No. 15B. Schedule Of Supplies/Services 15C. Quantity 15D. Unit 15E. Unit Price 15F. Amount SEE SCHEDULE CONTRACT TYPE: KIND OF CONTRACT: Firm-Fixed-Price Supply Contracts and Priced Orders Contract Expiration Date: 2009APR30 15G. -

Reinventing the Sword

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan Charles Edward Ethridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ethridge, Charles Edward, "Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3729. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE SWORD: A CULTURAL COMPARISON OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SWORD IN RESPONSE TO THE ADVENT OF FIREARMS IN SPAIN AND JAPAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Charles E. Ethridge B.A., Louisiana State University, 1999 December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Fredrikke Scollard, whose expertise, understanding, and patience added considerably to my graduate experience. I appreciate her knowledge of Eastern cultures and her drive to promote true ‘cross-cultural’ research. -

Knewslettter

KNIFEOKCA 39th Annual SHOW • April 12-13 Lane Events Center EXHIBIT HALL • Eugene, Oregon April 2014 Our international membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” YOU ARE INVITED TO THE OKCA 39th ANNUAL KNIFE SHOW & SALE April 12 - 13 * Lane Events Center & Fairgrounds, Eugene, Oregon In the super large EXHIBIT HALL. Now 360 Tables! ELCOME to the Oregon Knife Collectors demonstrations on Saturday. This year we have Anyone can enter to bid in the Silent Auction. See WAssociation Special Show Knewslettter. Blade Forging, Flint Knapping, quality Kitchen the display cases at the Club table to make a bid On Saturday, April 12, and Sunday, April 13, we Cutlery seminar, Knife Handle Designs, Martial on some extra special knives . want to welcome you and your friends and family Arts, Scrimshaw, Self Defense and Sharpening Along the side walls, we will have twenty to the famous and spectacular OREGON KNIFE Knives. three MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND SHOW & SALE. Now the Largest organizational Don’t miss the FREE knife identifi cation and CUTLERY COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY for Knife Show East & West of the Mississippi River. appraisal by Tommy Clark from Marion, VA your enjoyment and education, in addition to our The OREGON KNIFE SHOW happens just (Table N01) - Mark Zalesky from Knoxville TN hundreds of tables of hand-made, factory and once a year, at the Lane Events Center EXHIBIT (Table N02) and Mike Silvey on military knives antique knives for sale. Now 360 tables! When HALL, 796 West 13th Avenue in Eugene, Oregon. is from Pollock Pines CA (Table J14). -

Bayonet Updated

NEWS OF OUR CLIENTS 668 Flinn Ave Suite 28 Tel 805 529 3700 Contact: Jonina Costello / [email protected] Moorpark CA 93021 Fax 805 529 3701 Jason Bear / [email protected] Phone: (805) 529-3700 ONTARIO KNIFE COMPANY® OKC3S™ MARINE BAYONET Ontario Knife Company® is the designer and sole producer of the OKC3S™ Marine Bayonet and manufacturer of several other military products including but not limited to M9/M7 bayonets, A.S.E.K. survival knives, strap cutters and machetes for the military and other government/law enforcement entities. All of Ontario Knife Company’s military blades/tools are manufactured at the company’s Franklinville, New York facility. The Ontario Knife Company workforce possesses more than 800 years of collective knife making experience. “We take pride in our military products and it’s an honor and privilege to supply these weapons/tools to the US military,” said Ken Trbovich, President and CEO of Ontario Knife Company. “The military deploys our products for a wide range of combat and field operations, these include but are not limited to breaching devices, rescue tools and combat weapons,” he added. Ontario Knife Company cannot comment on the overall procurement rate or inventory levels of military bayonets. Ontario Knife Company military products, including the OKC3S Marine Bayonet, M9/M7 Bayonets, A.S.E.K. survival knives, 499 Air Force Survival Knife, 1-18” Military Machete, strap cutter and the MK 3 Navy Knife are also significantly popular in the consumer market. Key features of the Ontario Knife OKC3S Marine Bayonet are as follows: • 13.25” (33.65 cm) overall length • 1095 steel with a hardness rating of 53-58 HRC • 1.75 mission serration • Full-tang construction • Zinc phosphate non-reflective finish • Dynaflex® handle ergonomically grooved to reduce hand fatigue • Manufactured with a low noise signature polyester elastomer • Fitted internal stainless steel spring friction to secure bayonet • Lightweight • Molle compatible sheath designed for superior stealth Founded in 1889, The Ontario Knife Company is a U.S. -

KT AUCTIONS Military Collectables Auction

KT AUCTIONS Military Collectables Auction SUNDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2019 @ 11am AT BROADVIEW MASONIC CENTRE 565/567 REGENCY ROAD BROADVIEW SA Inspection from 9am day of sale Auctioneer - Kevin Tarling - Phone 0438 802 390 11% Buyers Premium applies - all prices GST inclusive SPECIAL CONDITIONS 1 No ammunition can be purchased without correct licence 2 No firearm can be purchased without correct licence 3 Firearms cannot be taken on the day unless you are a licensed gun dealer 4 All firearms will be held by a licensed dealer until your 30 day approval to purchase form is returned to you 5 All firearms are sold as is, where is, no guarantee is given or implied to the safety to shoot any firearm. It is recommended you have all weapons checked by a licensed gunsmith 6 If you are not sure on any firearm matter, please check with your local Police Station or ring Firearms Branch on 8204 2512 7 Do not leave the auction room without your approval to purchase forms INDEX PAGE 2 Knives Lots 1 – 28 2 Flying Caps – Lots 29 - 34 2 Pith Helmets – Lots 34a – 34d 3 Powder Flask Shot Flask – Lots 35 – 56 3 American Officers Peak Caps – Lots 57 - 67 3 Other Helmets & Hats – Lots 68 – 73 4 Sundry Items – Lots 74 – 123b 5 Bayonets – Lots 124 - 130 5 Uniforms – Lots 131 – 143 6 Swords – Lots 144 – 162 6 Flintlock Pistols – No Licence Required – Lots 163 – 166a 7 Antique Long Arms – No Licence Required –Lots 167 – 190 8 Percussion Pistol – Licence Required – Lots 191 – 192 8 Longarms – Licence Required – Lots 193 - 228 NOTE All firearms are being held by CHASE TARLING