An Examination of Self-Presentation of Nba Wives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibition Game.Indd

NATIONAL TITLES 1935 SEC CHAMPIONS 2015-16 1935 • 1953 • 1954 • 1979 • 1981 1985 • 1991 • 2000 • 2006 • 2009 BASKETBALL NCAA FINAL FOUR LSU 1953 • 1981 • 1986 • 2006 LSU Fighting Tigers vs. Southwest Baptist EX Exhibition Game No. 1 *Pete Maravich Assembly Center * Baton Rouge, La. November 6, 2015 * 7 p.m. CT * Streaming Video: SECN+ * Radio: LSU Sports Radio Network LSU (0-0, 0-0) LSU POSSIBLE STARTING LINEUP H - 0-0; A - 0-0; N - 0-0; OT - 0-0 (G) Jalyn Patterson November No. 15 * So. * 6-1 * 183 * Alpharetta, Georgia Fri. 13 MCNEESE STATE (ESPNU) 8 p.m. 2015-16 Averages Notables Recent Games LEGENDS CLASSIC In Australia, played all 5 gms Point guard at Montverde 10 gms in double figures Mon. 16 KENNESAW STATE (ESPNU) 8 p.m. primarily backup point guard Captured two ESPN national titles in 2015; season best 20 Thurs. 19 SOUTH ALABAMA (SECN) 8 p.m. 13 mpg, 2.2 ptts, 1.2 rpg 2013, hit game-winning 3 in National Final at Arkansas Mon. 23 vs. Marquette (ESPN2) 6 p.m. 4 assists, 6 steals Started final 11 in ‘15; 6.8 ppg, 2.2 apg Tues. 24 vs. NC State/Arizona State (ESPN2/U) TBA Mon. 30 at Charleston 6 p.m. December (G) Antonio Blakeney Wed. 2 NORTH FLORIDA (SECN+) 7 p.m. No. 2 * Fr. * 6-4 * 190 * Orlando, Florida Sun. 13 at Houston (ESPNU) 7 p.m. 2014-15 Averages Notables Recent Games Wed. 16 GARDNER-WEBB (SECN) 6 p.m. Sat. 19 ORAL ROBERTS (SECN) 7 p.m. -

Probable Starters

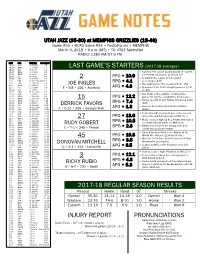

UTAH JAZZ (35-30) at MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES (18-46) Game #66 • ROAD Game #34 • FedExForum • MEMPHIS March 9, 2018 • 6 p.m. (MT) • TV: AT&T SportsNet RADIO: 1280 AM/97.5 FM DATE OPP. TIME (MT) RECORD/TV 10/18 DEN W, 106-96 1-0 10/20 @MIN L, 97-100 1-1 LAST GAME’S STARTERS (2017-18 averages) 10/21 OKC W, 96-87 2-1 10/24 @LAC L, 84-102 2-2 • Notched first career double-double (11 points, 10/25 @PHX L, 88-97 2-3 career-high 10 assists) at IND on 3/7 10/28 LAL W, 96-81 3-3 PPG • 10.9 10/30 DAL W, 104-89 4-3 2 • Second in the league in three-point 11/1 POR W, 112-103 (OT) 5-3 RPG • 4.1 percentage (.445) 11/3 TOR L, 100-109 5-4 JOE INGLES • Has eight games this season with 5+ 3FG 11/5 @HOU L, 110-137 5-5 11/7 PHI L, 97-104 5-6 F • 6-8 • 226 • Australia APG • 4.3 • Appeared in his 200th straight game on 2/24 11/10 MIA L, 74-84 5-7 vs. DAL 11/11 BKN W, 114-106 6-7 11/13 MIN L, 98-109 6-8 • Has made a three-pointer in consecutive 11/15 @NYK L, 101-106 6-9 PPG • 12.2 games for just the second time in his career 11/17 @BKN L, 107-118 6-10 15 11/18 @ORL W, 125-85 7-10 RPG • 7.4 • Ranks seventh in Jazz history in blocked shots 11/20 @PHI L, 86-107 7-11 DERRICK FAVORS (641) 11/22 CHI W, 110-80 8-11 Jazz are 11-3 when he records a double- 11/25 MIL W, 121-108 9-11 • APG • 1.3 11/28 DEN W, 106-77 10-11 F • 6-10 • 265 • Georgia Tech double 11/30 @LAC W, 126-107 11-11 st 12/1 NOP W, 114-108 12-11 • Posted his 21 double-double of the season 12/4 WAS W, 116-69 13-11 27 PPG • 13.6 (23 points and 14 rebounds) at IND (3/7) 12/5 @OKC L, 94-100 13-12 • Made a career-high 12 free throws and scored 12/7 HOU L, 101-112 13-13 RPG • 10.5 12/9 @MIL L, 100-117 13-14 RUDY GOBERT a season-high 26 points vs. -

2013-14 UCLA Women's Basketball Schedule

Table of Contents 5 12 51 Noelle Quinn Atonye Nyingifa Cori Close The 2013-14 Bruins UCLA's Top Single-Season Team Performances .......35 Credits Freshman Single-Season Leaders .................................36 Table of Contents .............................................................. 1 The 2013-14 UCLA Women’s Basketball Record Book was compiled Class Single-Season Leaders ..........................................37 2013-14 Schedule .............................................................. 2 by Ryan Finney, Associate Athletic Communications Director, with Yearly Individual Leaders ................................................38 assistance from Liza David, Director of Athletic Communications, Radio/TV Roster ................................................................ 3 By the Numbers ..............................................................40 Special assistance also provided by James Ybiernas, Assistant Athletic Alphabetical & Numerical Rosters .................................4 UCLA’s Home Court Records .....................................41 Communications Director and Steve Rourke, Associate Athletic Head Coach Cori Close ...................................................5 Communications Director. Primary photography by ASUCLA Pauley Pavilion - Home of the Bruins ..........................42 Assistant Coach Shannon Perry ..................................... 6 Campus Studio (Don Liebig and Todd Cheney). Additional photos provided by Scott Chandler, Thomas Campbell, USA Basketball, Assistant Coach Tony Newnan....................................... -

June 7 Redemption Update

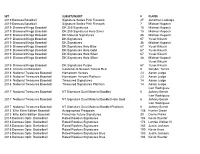

SET SUBSET/INSERT # PLAYER 2019 Donruss Baseball Signature Series Pink Firework 27 Jonathan Loaisiga 2019 Donruss Baseball Signature Series Pink Firework 7 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK 205 Signatures 15 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK 205 Signatures Holo Silver 15 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Material Signatures 36 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures 36 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Blue 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Gold 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Silver 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Silver 36 Michael Kopech Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Purple 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2018 Chronicles Baseball Contenders Season Tickets Red 6 Gleyber Torres 2018 National Treasures Baseball Hometown Heroes 23 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Hometown Heroes Platinum 23 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Treasured Signatures 14 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Treasured Signatures Platinum 14 Aaron Judge Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet 6 Johnny Bench Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet Holo Gold 6 Johnny Bench Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet Platinum 6 Johnny Bench 2013 Elite Extra Edition Baseball -

Lee Tao Dana

Lee Tao Dana Phone: _+660800498548 Email: [email protected] Citizenship: USA SUMMARY OF EXPERIENCE ● Experienced Basketball Coach in USA and Internationally ● General Manager, International Professional Basketball ● Special Assistant, National Basketball Association ● Assistant Coach, National Basketball Association Development League ● College/University/High School Basketball Coach ● Television Basketball Analyst and Play-by-Play Announcer ● Game Day Operations for National Basketball Association Development League ● Motivational Speaker EXPERIENCE Head Coach and General Manager Thang Long Warriors Vietnam Basketball Association (VBA) Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017 to Present Head Coach Dunkin’ Raptors Thailand Basketball Super League (TBSL) Bangkok, Thailand, 2016-2017 Head Men's Basketball Coach/Coordinator for Bachelor Degree Program Webster University Bangkok, Thailand, 2013-2016 Basketball Television Analyst and Play-by-Play Announcer FOX Sports Asia, ASEAN Basketball League (ABL) Bangkok, Thailand, 2012-2014 Assistant Basketball Coach Idaho Stampede (Utah Stars) National Basketball Association Development League (D-League) USA 2009 to 2011 Motivational Speaker Worldwide, 2002 to Present OTHER EXPERIENCE Special Assistant Golden State Warriors (National Basketball Association) Oakland, California, USA Basketball Coach Santa Rosa Junior College Santa Rosa, California, USA Basketball Coach Foothill College Los Altos, California, USA International Basketball Camps and Clinics Coach China, Japan, South Korea, USA, Vietnam OTHER Basketball -

2020 UNC Women's Soccer Record Book

2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book 1 2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book Carolina Quick Facts Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2020 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents, Quick Facts........................................................................ 2 Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2019 Roster, Pronunciation Guide................................................................... 3 2020 Schedule................................................................................................. 4 Enrollment: 18,814 undergraduates, 11,097 graduate and professional 2019 Team Statistics & Results ....................................................................5-7 students, 29,911 total enrollment Misc. Statistics ................................................................................................. 8 Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz Chancellor: Losses, Ties, and Comeback Wins ................................................................. 9 Bubba Cunningham Director of Athletics: All-Time Honor Roll ..................................................................................10-19 Larry Gallo (primary), Korie Sawyer Women’s Soccer Administrators: Year-By-Year Results ...............................................................................18-21 Rich (secondary) Series History ...........................................................................................23-27 Senior Woman Administrator: Marielle vanGelder Single Game Superlatives ........................................................................28-29 -

Camp 6 Construction Coming Along

15 Minutes of Fame, pg. 11 Volume 6, Issue 131 www.jtfgtmo.southcom. www.jtfgtmo.southcom. mil mil Friday, Friday, November April 8, 4,2005 2005 15 Minutes of Fame, pg. 11 Camp 6 construction coming along By Spc. Jeshua Nace JTF-GTMO Public Affairs Office Camp 6 is a medium security deten- tion facility designed to improve opera- tional and personnel capabilities while maximizing the use of technology and providing a better quality of life for de- tainees. “With the exception of Camp 5, Camp 6 is different than Camps 1 through 4 by providing climate controlled interior liv- ing, dining, and a medical and dental unit within the building,” said Navy Cmdr. Anne Reese, offi cer in charge of engi- neering. In addition, Camp 6 will provide com- munal gathering and recreation areas. “There will be four recreation areas, one is a large ball fi eld measuring 150 Photo by Spc. Jeshua Nace feet by 50 feet, where organized sports The fi rst cells of Camp 6 have been placed. Contractors are pouring the can be played and they can run laps. All concrete for the rest of the Camp 6. recreation areas are built to be communal rather than individual use,” she said. construction of Camp 6 recently. whole building remains to be built from Besides increasing the recreation area, The project was scheduled to be com- the slab up. There are several pre-fab- the new facility is a more permanent pleted in June 2006 has been pushed ricated components of the building that structure. back by the recent weather. -

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball Louisville Basketball Tradition asketball is special to Kentuckians. The sport B permeates everyday life from offices to farm- lands, from coal mines to neighborhood drug stores. It is more than just a sport played in the cold winter months. It is a source of pride filled year-round with anticipation, hope and celebration. Kentuckians love their basketball, and the tradition-rich University of Louisville program has supplied its fans with one of the nation’s finest products for decades. Legendary coach Bernard “Peck” Hickman, a Basketball Hall of Fame nominee, arrived on the UofL campus in 1944 to begin a remarkable string of 46 consecutive winning seasons. For 23 seasons, Hickman laid an impressive foundation for UofL. John Dromo, an assistant coach under Hickman for 19 years, continued the Louisville program in outstanding fashion following Hickman’s retirement. For 30 years, Denny Crum followed the same path of success that Hickman and Dromo both walked, guiding the Cardinals to even higher acclaim. Now, Coach Rick Pitino energized a re-emergence in building upon the rich UofL tradition in his 16 years, guiding the Cardinals to the 2013 NCAA championship, NCAA Final Fours in 2005 and 2012 and the NCAA Elite Eight five of the past 10 sea- sons. Among the Cardinals’ past successes include national championships in the NCAA (1980,1986, 2013), NIT (1956) and the NAIB (1948). UofL is Taquan Dean kisses the Freedom Hall floor Tremendous pride is taken in the tradition the only school in the nation to have claimed the after his final game as a Cardinal. -

Box Score Wizards

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL SCORER'S REPORT FINAL BOX Saturday, May 1, 2021 American Airlines Center, Dallas, TX Officials: #24 Kevin Scott, #3 Nick Buchert, #17 Jonathan Sterling Game Duration: 2:14 Attendance: 4351 (Sellout) VISITOR: Washington Wizards (29-35) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 3 Bradley Beal F 36:45 9 20 1 5 10 11 1 3 4 3 4 2 3 0 0 29 8 Rui Hachimura F 28:34 7 11 1 2 3 5 1 1 2 0 3 0 2 0 -3 18 27 Alex Len C 04:47 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 -11 0 19 Raul Neto G 29:27 3 5 0 1 2 2 1 8 9 4 3 0 0 0 12 8 4 Russell Westbrook G 40:12 17 30 3 6 5 7 2 8 10 9 4 2 2 0 -3 42 21 Daniel Gafford 25:09 4 5 0 0 1 2 5 2 7 0 2 0 0 2 -7 9 42 Davis Bertans 25:34 1 5 1 5 2 3 0 3 3 0 1 0 0 1 4 5 14 Ish Smith 23:59 3 8 0 0 0 0 1 3 4 2 3 1 2 0 -3 6 1 Chandler Hutchison 07:38 1 2 0 0 0 0 1 1 2 0 1 0 0 0 -11 2 15 Robin Lopez 17:55 2 3 0 0 1 1 2 2 4 0 1 0 1 0 17 5 17 Isaac Bonga DNP - Coach's decision 16 Anthony Gill DNP - Coach's decision 24 Garrison Mathews DNP - Coach's decision 5 Cassius Winston DNP - Coach's decision 240:00 47 91 6 19 24 31 14 32 46 19 23 5 10 3 -1 124 51.6% 31.6% 77.4% TM REB: 6 TOT TO: 11 (12 PTS) HOME: DALLAS MAVERICKS (36-27) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 10 Dorian Finney-Smith F 40:29 8 12 6 9 0 0 1 4 5 2 2 1 3 0 4 22 42 Maxi Kleber F 27:07 5 9 5 9 2 2 0 1 1 1 2 0 1 1 -6 17 7 Dwight Powell C 18:52 3 5 0 0 5 6 1 2 3 0 3 0 0 0 1 11 0 Josh Richardson G 23:18 3 11 1 5 1 1 0 0 0 2 0 2 4 1 -6 8 77 Luka Doncic G 39:13 12 23 1 6 6 11 2 10 12 20 4 0 1 0 6 31 33 Willie Cauley-Stein 26:46 3 5 0 1 0 0 3 9 12 0 4 2 1 2 -3 6 11 Tim Hardaway Jr. -

NBA INFORMATION 2018-19 NBA Standings NBA Eastern Conference NBA Western Conference

NBA INFORMATION 2018-19 NBA Standings NBA Eastern Conference NBA Western Conference ATLANTIC DIVISION SOUTHWEST DIVISION W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK Toronto 58 24 .707 - 32- 9 26-15 7-3 Won 2 Houston 53 29 .646 - 31-10 22-19 8-2 Lost 1 Philadelphia 51 31 .622 7 31-10 20-21 4-6 Won 1 San Antonio 48 34 .585 5 32- 9 16-25 6-4 Won 3 Boston 49 33 .598 9 28-13 21-20 6-4 Won 1 Dallas 33 49 .402 20 24-17 9-32 5-5 Lost 1 Brooklyn 42 40 .512 16 23-18 19-22 6-4 Won 3 Memphis 33 49 .402 20 21-20 12-29 4-6 Won 1 New York 17 65 .207 41 9-32 8-33 3-7 Lost 1 New Orleans 33 49 .402 20 19-22 14-27 3-7 Lost 1 CENTRAL DIVISION NORTHWEST DIVISION W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK Milwaukee 60 22 .732 - 33- 8 27-14 7-3 Lost 1 Denver 54 28 .659 - 34- 7 20-21 5-5 Won 1 Indiana 48 34 .585 12 29-12 19-22 4-6 Won 1 Portland 53 29 .646 1 32- 9 21-20 8-2 Won 3 Detroit 41 41 .500 19 26-15 15-26 4-6 Won 2 Utah 50 32 .610 4 29-12 21-20 8-2 Lost 1 Chicago 22 60 .268 38 9-32 13-28 2-8 Lost 3 Oklahoma City 49 33 .598 5 27-14 22-19 7-3 Won 5 CLEVELAND 19 63 .232 41 13-28 6-35 0-10 Lost 10 Minnesota 36 46 .439 18 25-16 11-30 4-6 Lost 3 SOUTHEAST DIVISION PACIFIC DIVISION W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK W L PCT GB HOME ROAD LAST-10 STREAK Orlando 42 40 .512 - 25-16 17-24 8-2 Won 4 Golden State 57 25 .695 - 30-11 27-14 8-2 Lost 1 Charlotte 39 43 .476 3 25-16 14-27 6-4 Lost 1 L.A. -

Racism in the Ron Artest Fight

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4zr6d8wt Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 13(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Williams, Jeffrey A. Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/LR8131027082 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" by Jeffrey A. Williams* "There's a reason. But I don't think anybody ought to be surprised, folks. I really don't think anybody ought to be surprised. This is the hip-hop culture on parade. This is gang behavior on parade minus the guns. That's what the culture of the NBA has become." - Rush Limbaugh1 "Do you really want to go there? Do I have to? .... I think it's fair to say that the NBA was the first sport that was widely viewed as a black sport. And whatever the numbers ultimately are for the other sports, the NBA will always be treated a certain way because of that. Our players are so visible that if they have Afros or cornrows or tattoos- white or black-our consumers pick it up. So, I think there are al- ways some elements of race involved that affect judgments about the NBA." - NBA Commissioner David Stern2 * B.A. in History & Religion, Columbia University, 2002, J.D., Columbia Law School, 2005. The author is currently an associate in the Manhattan office of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. The views reflected herein are entirely those of the author alone. -

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS Media Guide

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS SEASON SCHEDULE HOME AWAY NOVEMBER FEBRUARY Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa OCT. 30 31 NOV. 1 2 3 1 2 MIA MIL WAS ORL MEM 8:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 WAS PHI MIL LAC MEM MEM TOR LAL MEM MEM 7:30 7:30 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:30 7:00 8:00 7:30 7:30 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 CHI UTA BRK TOR DEN CHA MEM CHI MEM MEM MEM 8:00 7:30 8:00 12:30 6:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 DET SAN OKC MEM MEM DEN LAL MEM PHO MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:AL30L-STAR 7:30 9:00 10:30 7:30 9:00 7:30 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 ORL BRK POR POR UTA MEM MEM MEM 6:00 7:30 7:30 9:00 9:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 DECEMBER MARCH Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 1 2 MIL GSW MEM 8:30 7:30 7:30 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 MEM MEM MEM MIN MEM PHI PHI MEM MEM PHI IND MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 MEM MEM MEM DAL MEM HOU SAN OKC MEM CHA TOR MEM MEM CHA 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 MEM MEM CHI CLE MEM MIL MEM MEM MIA MEM NOH MEM DAL MEM 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:30 8:00 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 MEM MEM BRK MEM LAC MEM GSW MEM MEM NYK CLE MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 12:00 7:30 10:30 7:30 10:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 30 31 31 SAC MEM NYK 9:00 7:30 7:30 JANUARY APRIL Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 MEM MEM MEM IND ATL MIN MEM DET MEM CLE MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00