PDF (Volume 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mavis Dixon VAD Database.Xlsx

County Durham Voluntary Aid Detachment workers, 1914-1919 www.durhamatwar.org.uk Surname Forename Address Role Further information Service from 2/1915 to 12/1915 and 7/1916 to 8/1917. 13th Durham Margaret Ann Mount Stewart St., V.A.H., Vane House, Seaham Harbour. Husband George William, Coal Lacey Nurse. Part time. 1610 hours worked. (Mrs) Dawdon Miner/Stoneman, son Benjamin. Born Felling c1880. Married 1901 Easington District – maiden name McElwee. Bon Accord, Foggy Furze, Service from 12/1915 to date. 8th Durham V.A.H., Normanhurst, West Ladyman Grace Cook. Part time. 2016 hours worked. West Hartlepool Hartlepool. Not in Hartlepool 1911. C/o Mrs. Atkinson, Service from 1915 to 1/1917. 17th Durham V.A.H., The Red House, Laidler Mary E Wellbank, Morpeth. Sister. Full time. Paid. Etherley, Bishop Auckland. Too many on 1911 census to get a safe Crossed out on the card. match. Service from 1/11/1918 to 1/4/1919. Oulton Hall (Officers’ Hospital), C/o Mrs J Watson, 39 High Waitress. Pay - £26 per annum. Full Laine Emily Leeds. Attd. Military Hospital, Ripon 6/1918 and 7/1918. Not in Crook Jobs Hill, Crook time. on 1911 census. 7 Thornhill Park, Kitchen helper. 30 hours alternate Service from 12/1917 to 2/1919. 3rd Durham V.A.H., Hammerton Laing E. Victoria Sunderland weeks. House, 4 Gray Road, Sunderland. Unable to trace 1911 census. Lake Frank West Park Road, Cleadon Private. Driver. Service from 30/2/1917 to 1919. Unable to trace 1911 census. 15 Rowell St., West Service from 19/2/1917 to 1919. -

Spennymoor Area Action Partnership Action Area

Spennymoor Area Action Partnership Area Annual Review 2013/14 Spennymoor AAP – Annual Review 2013/14 Foreword from Alan Smith, Outgoing Spennymoor AAP Chair I would like to thank everyone associated with the Spennymoor Area Action Partnership for contributing to another excellent year in moving forward and trying to make a real difference in the AAP area. Having been given a clear steer on the need to continue with the key priorities of Children & Young People and Employment and Job Prospects, there has been a real drive and energy to succeed. The major occasion of our year, held in November, was the ‘Your Money, Your Area, Your Views’ event. The event provided the opportunity for members of our communities to vote on projects they wanted to receive funding, to vote on the AAP priorities for the 2014/15 financial year and to have their say on the future budget for Durham County Council (DCC). Overall the event was a great success with over 900 people attending on the day. The event also showed how committed the people of our area are to supporting and improving the community they live and work in. Taking community cohesion one step further, it was great to see that the community engagement processes that have been put in place by DCC (AAPs being pivotal in this) were a key element of the LGC Council of The Year award given to DCC recently. A major role in DCC achieving this accolade was a full day of assessment by an independent panel and for me it was a real boost that our partnership was selected to be part of this judging day. -

104 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

104 bus time schedule & line map 104 Ramshaw - Newƒeld View In Website Mode The 104 bus line (Ramshaw - Newƒeld) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bishop Auckland: 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM (2) Newƒeld: 9:15 AM - 5:10 PM (3) Ramshaw: 9:31 AM - 2:01 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 104 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 104 bus arriving. Direction: Bishop Auckland 104 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Bishop Auckland Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM Bus Stand, Newƒeld Tuesday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM Primrose Hill, Newƒeld Wednesday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM High Row, Newƒeld Thursday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM Primrose Hill, England Friday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM Wear View, Todhills Saturday 8:11 AM - 3:36 PM School, Byers Green Wear View, Byers Green Methodist Church, Byers Green 104 bus Info Robinson Terrace, Spennymoor Civil Parish Direction: Bishop Auckland Stops: 29 Wilkinson Street, Byers Green Trip Duration: 18 min Line Summary: Bus Stand, Newƒeld, Primrose Hill, War Memorial, Byers Green Newƒeld, High Row, Newƒeld, Wear View, Todhills, School, Byers Green, Wear View, Byers Green, Methodist Church, Byers Green, Wilkinson Street, Church St - Railway Path, Byers Green Byers Green, War Memorial, Byers Green, Church St - Railway Path, Byers Green, Railway Cottages, Byers Railway Cottages, Byers Green Green, Common, Binchester, Church, Binchester, Lane Ends, Binchester, Garage, Binchester, Common, Binchester Westerton Lane End, Binchester, The Top House, Coundon Gate, Allotments, -

ON the WORK of MID DURHAM AAP… March 2018

A BRIEF ‘HEADS UP’ ON THE WORK OF MID DURHAM AAP… March 2018 WELCOME Welcome to your March edition of the AAPs e-bulletin / e-newsletter. In this month’s edition we will update you on: - Mid Durham’s next Board meeting - Community Snippets - Partner Updates For more detailed information on all our meetings and work (notes, project updates, members, etc) please visit our web pages at www.durham.gov.uk/mdaap or sign up to our Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/pages/Mid-Durham-Area-Action- Partnership-AAP/214188621970873 MID DURHAM AAP - March Board Meeting The Mid Durham AAP will be holding its next Board meeting on Wednesday 14th March 2018 at 6pm in New Brancepeth Village Hall, Rock Terrace, New Brancepeth, DH7 7EP On the agenda will be presentation on the proposed Care Navigator Programme which is a person-centred approach which uses signposting and information to help primary care patients and their carers move through the health and social care system. There will also be several Area Budget projects coming to the Board including the Deernees Paths and an Environment Improvement Pot that if approved will start later this year. We ask that you register your attendance beforehand by contacting us on 07818510370 or 07814969392 or 07557541413 or email middurhamaap.gov.uk. Community Snippets Burnhope – The Community Centre is now well underway and is scheduled for completion at the end of May. The builder – McCarricks, have used a drone to take photos… Butsfield Young Farmers – Similar to Burnhope, the young Farmers build is well under way too and is due for completion in mid-March… Lanchester Loneliness Project – Several groups and residents in Lanchester are working together to tackle social isolation within their village. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton Richardson, Martin Howard How to cite: Richardson, Martin Howard (1998) The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN COUNTY DURHAM, 1944-1974, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FERRYHILL AND CHILTON MARTIN HOWARD RICHARDSON This thesis grew out of a single question: why should a staunch Labour Party stronghold like County Durham open a grammar school in 1964 when the national Party was so firmly committed to comprehensivization? The answer was less easy to find than the question was to pose. -

Handlist 13 – Grave Plans

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Handlist 13 – Grave Plans Issue no. 6 July 2020 Introduction This leaflet explains some of the problems surrounding attempts to find burial locations, and lists those useful grave plans which are available at Durham County Record Office. In order to find the location of a grave you will first need to find which cemetery or churchyard a person is buried in, perhaps by looking in burial registers, and then look for the grave location using grave registers and grave plans. To complement our lists of churchyard burial records (see below) we have published a book, Cemeteries in County Durham, which lists civil cemeteries in County Durham and shows where records for these are available. Appendices to this book list non-conformist cemeteries and churchyard extensions. Please contact us to buy a copy. Parish burial registers Church of England burial registers generally give a date of burial, the name of the person and sometimes an address and age (for more details please see information about Parish Registers in the Family History section of our website). These registers are available to be viewed in the Record Office on microfilm. Burial register entries occasionally give references to burial grounds or grave plot locations in a marginal note. For details on coverage of parish registers please see our Parish Register Database and our Parish Registers Handlist (in the Information Leaflets section). While most burial registers are for Church of England graveyards there are some non-conformist burial grounds which have registers too (please see appendix 3 of our Cemeteries book, and our Non-conformist Register Handlist). -

2015 52 Brandon and Byshottles Parish Council

BRANDON AND BYSHOTTLES PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS 6 GOATBECK TERRACE, LANGLEY MOOR, DURHAM ON FRIDAY 16TH JANUARY 2015 AT 6.30 PM PRESENT Councillor T Akins (in the Chair) and Councillors Bell, Mrs Bonner, Mrs Chaplow, Clegg, Mrs Gates, Graham, Grantham, Jamieson, Jones, Mrs Rodgers, Stoddart, Sims, Taylor, Turnbull and Mrs Wharton 153. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest received. 154. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION There were no questions from the public in the specified time. 155. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Mrs Akins, Nelson, Mrs Nelson and Rippin. RESOLVED: To receive the apologies. 156. MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 19 TH DECEMBER 2014 RESOLVED: To add Councillors Graham and Sims apologies, then approve the minutes as a true record. 157. MINUTES OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE HELD ON 7TH JANUARY 2015 RESOLVED: To approve the minutes as a true record and to set a precept of £149,760 for 2015/16. 158. ATTENDANCE OF MAYOR OF DURHAM TO SAY PERSONAL THANK YOU FOR DONATION TO HIS CHARITY The Mayor and Mayoress of Durham were in attendance and thanked the Chairman and Members for their kind donation to his charity which was presented to him at the switch on of the Christmas lights in Langley Moor. The Chairman thanked the Mayor and Mayoress for their attendance. 2015 52 159. PRESENTATION OF DONATIONS The Chairman presented donations to the following:- Brandon Carrside Youth & Community Project The Hive Holocaust Memorial Day Lourdes Fund St. Luke’s Church 160. -

Brancepeth APPROVED 2009

Heritage, Landscape and Design Brancepeth APPROVED 2009 1 INTRODUCTION ............................ - 4 - 1.1 CONSERVATION AREAS ...................- 4 - 1.2 WHAT IS A CONSERVATION AREA?...- 4 - 1.3 WHO DESIGNATES CONSERVATION AREAS? - 4 - 1.4 WHAT DOES DESIGNATION MEAN?....- 5 - 1.5 WHAT IS A CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL? - 6 - 1.6 WHAT IS THE DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST,CHARACTER AND APPEARANCE? - 7 - 1.7 CONSERVATION AREA MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS - 7 - 1.8 WHO WILL USE THE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL? - 8 - 2 BRANCEPETH CONSERVATION AREA - 8 - 2.1 THE CONTEXT OF THE CONSERVATION AREA - 8 - 2.2 DESIGNATION ...............................- 10 - 2.3 DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA............- 10 - 2.4 SCHEDULE OF THE AREA ...............- 10 - 2.5 HISTORY OF THE AREA ..................- 12 - 3 CHARACTER ZONES .................. - 14 - 3.1 GENERAL .....................................- 14 - 3.2 ZONES A AND B............................- 15 - 3.3 ZONE C........................................- 16 - 3.4 ZONE D........................................- 17 - 3.5 ZONE E ........................................- 18 - 3.6 ZONES F, G AND H........................- 20 - 4 TOWNSCAPE AND LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS - 21 - 4.1 DISTINCTIVE CHARACTER...............- 21 - 4.2 ARCHAEOLOGY.............................- 22 - 4.3 PRINCIPAL LAND USE ...................- 22 - 4.4 PLAN FORM..................................- 22 - 4.5 VIEWS INTO, WITHIN AND OUT OF THE CONSERVATION AREA - 23 - 4.6 STREET PATTERNS AND SCENES ....- 24 - 4.7 PEDESTRIAN ROUTES ....................- -

![[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING and MECHANICAL](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2457/i-north-of-england-institute-of-mining-and-mechanical-712457.webp)

[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING and MECHANICAL

[i] NORTH OF ENGLAND INSTITUTE OF MINING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERS. TRANSACTIONS. VOL. XXI. 1871-72. NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE: A. REID, PRINTING COURT BUILDINGS, AKENSIDE HILL. 1872. [ii] Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Andrew Reid, Printing Court Buildings, Akenside Hill. [iii] CONTENTS OF VOL. XXI. Page. Report of Council............... v Finance Report.................. vii Account of Subscriptions ... viii Treasurer's Account ......... x General Account ............... xii Patrons ............................. xiii Honorary and Life Members .... xiv Officers, 1872-73 .................. xv Members.............................. xvi Students ........................... xxxiv Subscribing Collieries ...... xxxvii Rules ................................. xxxviii Barometer Readings. Appendix I.......... End of Vol Patents. Appendix II.......... End of Vol Address by the Dean of Durham on the Inauguration of the College of Physical Science .... End of Vol Index ....................... End of Vol GENERAL MEETINGS. 1871. page. Sept. 2.—Election of Members, &c 1 Oct. 7.—Paper by Mr. Henry Lewis "On the Method of Working Coal by Longwall, at Annesley Colliery, Nottingham" 3 Discussion on Mr. Smyth's Paper "On the Boring of Pit Shafts in Belgium... ... ... ... ... ... ... .9 Paper "On the Education of the Mining Engineer", by Mr. John Young ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 21 Discussed ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 32 Dec. 2.—Paper by Mr. Emerson Bainbridge "On the Difference between the Statical and Dynamical Pressure of Water Columns in Lifting Sets" 49 Paper "On the Cornish Pumping Engine at Settlingstones" by Mr. F.W. Hall ... 59 Report upon Experiments of Rivetting with Drilled and Punched Holes, and Hand and Power Rivetting 67 1872 Feb. 3.—Paper by Mr. W. N. Taylor "On Air Compressing Machinery as applied to Underground Haulage, &c, at Ryhope Colliery" .. 73 Discussed ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 80 Alteration of Rule IV. ... .. ... 82 Mar. -

52 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

52 bus time schedule & line map 52 Durham - East Hedleyhope View In Website Mode The 52 bus line (Durham - East Hedleyhope) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Durham: 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM (2) East Hedleyhope: 8:34 AM - 5:44 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 52 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 52 bus arriving. Direction: Durham 52 bus Time Schedule 66 stops Durham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Turning Circle, East Hedleyhope Tuesday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Deerness View, East Hedleyhope Deerness View, Hedleyhope Civil Parish Wednesday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Old Pit, East Hedleyhope Thursday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Friday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Stable House Farm, East Hedleyhope Saturday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Hedley Hill Terrace, Waterhouses Black Horse, Waterhouses Terrace, Waterhouses 52 bus Info Hamilton Row, Brandon And Byshottles Civil Parish Direction: Durham Stops: 66 Church, Waterhouses Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Turning Circle, East Hedleyhope, Old Co-Op Store, Waterhouses Deerness View, East Hedleyhope, Old Pit, East Hedleyhope, Stable House Farm, East Hedleyhope, Station Street, Brandon And Byshottles Civil Parish Hedley Hill Terrace, Waterhouses, Black Horse, Football Ground-Social Club, Waterhouses Waterhouses, Terrace, Waterhouses, Church, Waterhouses, Old Co-Op Store, Waterhouses, Football Ground-Social Club, Waterhouses, College College View, Esh Winning View, Esh Winning, Lymington Crossing, Esh Winning, Co-Operative Store, Esh Winning, -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

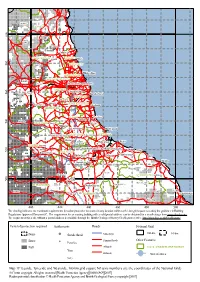

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright.