7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Matching

Art Matching Program Type: Demonstration or Classroom Audience Type: Grade 4–adult Program Description: Students explore how artists from different cultures have used art to represent space-related phenomena. Topics: Moon, space travel, art, stars, sky-watching Process Skills Focus: Critical thinking, observing, creativity. LEARNING OBJECTIVES For Next Generation Science Standards alignment, see end of outline. • Many artists are inspired by astronomy and the universe. • Cultures often have their own interpretations of the sky and celestial phenomena. • Art is one of many ways to capture our observations of and reflections on the sky. TIME REQUIRED Advance Prep Set Up Activity Clean Up 15 minutes 5 minutes 10 minutes 5 minutes SITE REQUIREMENTS • Table or other flat surface • Chairs (optional, but helpful for elderly or young audiences) Art Matching 1 Lenses on the Sky OMSI 2017 PROGRAM FORMAT Segment Format Time Introduction Large group discussion 2 min Art Matching Group Activity 5 min Wrap-Up Large group discussion 3 min SUPPLIES Permanent Supplies Amount Notes Laminated pages showing the artists 5 and their work Laminated cards showing 5 astronomical images ADVANCE PREPARATION • Print out, cut, and laminate the pages showing the artists and their work (at the end of the document). • Print out, cut, and laminate the five cards showing the astronomical images (at the end of the document). • Complete the activity to familiarize yourself with the process. SET UP Spread out the five pages showing the artists and their work on the table. Below the pages, place the five cards showing the astronomical objects. INTRODUCTION 2 minutes Let students speculate before offering answers to any questions. -

Ocabulary of Definitions : P

Service bibliothèque Catalogue historique de la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice Source : Monographie de l’Observatoire de Nice / Charles Garnier, 1892. Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur Février 2012 Présentation << On trouve… à l’Ouest … la bibliothèque avec ses six mille deux cents volumes et ses trentes journaux ou recueils périodiques…. >> (Façade principale de la Bibliothèque / Phot. attribuée à Michaud A. – 188? - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) C’est en ces termes qu’Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin décrivait la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice en 1899 dans l’introduction du tome 1 des Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice 1. Un catalogue des revues et ouvrages 2 classé par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs et de lieux décrivait le fonds historique de la bibliothèque. 1 Introduction, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. XIV 2 Catalogue de la bibliothèque, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. 1 Le présent document est une version remaniée, complétée et enrichie de ce catalogue. (Bibliothèque, vue de l’intérieur par le photogr. Jean Giletta, 191?. - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) Chaque référence est reproduite à l’identique. Elle est complétée par une notice bibliographique et éventuellement par un lien électronique sur la version numérisée. Les titres et documents non encore identifiés sont signalés en italique. Un index des auteurs et des titres de revues termine le document. -

Spring Fever Strikes

The MARCH 2002 DENVER OBSERVER Newsletter of the Denver Astronomical Society One Mile Nearer the Stars How Many in One Night?? Gearing up for the Messier Marathon? Those folks who are new to astronomy may not yet be able to relate to the sheer joy of braving the early-spring temperatures (brrrrr) for a full night (and morning—I’m talking dusk to dawn, here) of observing some of the most beautiful objects in the heavens. Why now? Because for only a few weeks during the year is it possible to see all of the Messier objects in one night. Astronomers will dig in their heels and tripods, get out the star charts (See Page 7), and knock off one object after the next. Some people actually catalog 70 of the available 110 targets and submit their achievements to the Astronomical League for the coveted Messier Certificate. Others just like to look at the beautiful celestial wonders like the one in the photo to the left. Either way, get out to the The Pleaides (M45) DSS on the weekend of the 15th and enjoy Image © Joe Gafford, 2002 the views!—PK Spring Fever Strikes President’s Corner .......... 2 MARCH SKIES 2002 f you’ve been reading your astronomy magazines, you know that by month’s Schedule of Events ......... 2 Iend, four naked-eye planets will grace the night skies. Jupiter is the main show-stopper but Saturn, Mars, and finally Venus will sparkle for all, moon or no moon. Remember that a Officers ......................... 2 little high-cloud haze can be good for telescopic planet observations. -

What's up This Month – December 2019 These Pages Are Intended to Help You Find Your Way Around the Sky

WHAT'S UP THIS MONTH – DECEMBER 2019 THESE PAGES ARE INTENDED TO HELP YOU FIND YOUR WAY AROUND THE SKY The chart above shows the night sky as it appears on 15th December at 21:00 (9 o’clock) in the evening Greenwich Meantime Time (GMT). As the Earth orbits the Sun and we look out into space each night the stars will appear to have moved across the sky by a small amount. Every month Earth moves one twelfth of its circuit around the Sun, this amounts to 30 degrees each month. There are about 30 days in each month so each night the stars appear to move about 1 degree. The sky will therefore appear the same as shown on the chart above at 10 o’clock GMT at the beginning of the month and at 8 o’clock GMT at the end of the month. The stars also appear to move 15º (360º divided by 24) each hour from east to west, due to the Earth rotating once every 24 hours. The centre of the chart will be the position in the sky directly overhead, called the Zenith. First we need to find some familiar objects so we can get our bearings. The Pole Star Polaris can be easily found by first finding the familiar shape of the Great Bear ‘Ursa Major’ that is also 1 sometimes called the Plough or even the Big Dipper by the Americans. Ursa Major is visible throughout the year from Britain and is always easy to find. This month it is in the north east. -

02 Southern Cross

Asterism Southern Cross The Southern Cross is located in the constellation Crux, the smallest of the 88 constellations. It is one of the most distinctive. With the four stars Mimosa BeCrux, Ga Crux, A Crux and Delta Crucis, forming the arms of the cross. The Southern Cross was also used as a remarkably accurate timepiece by all the people of the southern hemisphere, referred to as the ‘Southern Celestial Clock’ by the portuguese naturalist Cristoval D’Acosta. It is perpendicular as it passes the meridian, and the exact time can thus be calculated visually from its angle. The german explorer Baron Alexander von Humboldt, sailing across the southern oceans in 1799, wrote: “It is a timepiece, which advances very regularly nearly 4 minutes a day, and no other group of stars affords to the naked eye an observation of time so easily made”. Asterism - An asterism is a distinctive pattern of stars or a distinctive group of stars in the sky. Constellation - A grouping of stars that make an imaginary picture in the sky. There are 88 constellations. The stars and objects nearby The Main-Themes in asterism Southern Cross Southern Cross Ga Crux A Crux Mimosa, Be Crux Delta Crucis The Motives in asterism Southern Cross Crucis A Bayer / Flamsteed indication AM Arp+Madore - A Catalogue of Southern peculiar Galaxies and Associations [B10] Boss, 1910 - Preliminary General Catalogue of 6188 Stars C Cluster CCDM Catalogue des composantes d’étoiles doubles et multiples CD Cordoba Durchmusterung Declination Cel Celescope Catalog of ultraviolet Magnitudes CPC -

Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae

Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae By Dave Knisely Light Pollution and various “nebula” filters have been around since the late 1970’s, and amateurs have been using them ever since to bring out detail (and even some objects) which were difficult to impossible to see before in modest apertures. When I started using them in the early 1980’s, specific information about which filter might work on a given object (or even whether certain filters were useful at all) was often hard to come by. Even those accounts that were available often had incomplete or inaccurate information. Getting some observational experience with the Lumicon line of filters helped, but there were still some unanswered questions. I wondered how the various filters would rank on- average against each other for a large number of objects, and whether there was a “best overall” filter. In particular, I also wondered if the much-maligned H-Beta filter was useful on more objects than the two or three targets most often mentioned in publications. In the summer of 1999, I decided to begin some more comprehensive observations to try and answer these questions and determine how to best use these filters overall. I formulated a basic survey covering a moderate number of emission and planetary nebulae to obtain some statistics on filter performance to try to address the following questions: 1. How do the various filter types compare as to what (on average) they show on a given nebula? 2. Is there one overall “best” nebula filter which will work on the largest number of objects? 3. -

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16H 41M 42S DEC(2000): +36° 27'

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16h 41m 42s DEC(2000): +36° 27’ 41” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Globular Cluster CONSTELLATION: Hercules BEST VIEW: Late July DISCOVERY: Edmond Halley, 1714 DISTANCE: 25,100 ly DIAMETER: 145 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +5.8 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 20’ Starry Night FOV: 1.00 Lyra FOV: 60.00 Libra MESSIER 6 (Butterfly Cluster) RA(2000) : 17Ophiuchus h 40m 20s DEC(2000): -32° 15’ 12” M6 Sagitta Serpens Cauda Vulpecula Scutum Scorpius Aquila M6 FOV: 5.00 Telrad Delphinus Norma Sagittarius Corona Australis Ara Equuleus M6 Triangulum Australe BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster Telescopium CONSTELLATION: Scorpius Capricornus BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Giovanni Batista Hodierna, c. 1654 DISTANCE: 1600 ly MicroscopiumDIAMETER: 12 – 25 ly Pavo APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +4.2 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 25’ – 54’ AGE: 50 – 100 million years Telrad Indus MESSIER 7 (Ptolemy’s Cluster) RA(2000) : 17h 53m 51s DEC(2000): -34° 47’ 36” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster CONSTELLATION: Scorpius BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Claudius Ptolemy, 130 A.D. DISTANCE: 900 – 1000 ly DIAMETER: 20 – 25 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +3.3 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 80’ AGE: ~220 million years FOV:Starry 1.00Night FOV: 60.00 Hercules Libra MESSIER 8 (THE LAGOON NEBULA) RA(2000) : 18h 03m 37s DEC(2000): -24° 23’ 12” Lyra M8 Ophiuchus Serpens Cauda Cygnus Scorpius Sagitta M8 FOV: 5.00 Scutum Telrad Vulpecula Aquila Ara Corona Australis Sagittarius Delphinus M8 BASIC INFORMATION Telescopium OBJECT TYPE: Star Forming Region CONSTELLATION: Sagittarius Equuleus BEST -

Messier Plus Marathon Text

Messier Plus Marathon Object List by Wally Brown & Bob Buckner with additional objects by Mike Roos Object Data - Saguaro Astronomy Club Score is most numbered objects in a single night. Tiebreaker is count of un-numbered objects Observer Name Date Address Marathon Obects __________ Tiebreaker Objects ________ SEQ OBJECT TYPE CON R.A. DEC. RISE TRANSIT SET MAG SIZE NOTES TIME M 53 GLOCL COM 1312.9 +1810 7:21 14:17 21:12 7.7 13.0' NGC 5024, !B,vC,iR,vvmbM,st 12.. NGC 5272, !!,eB,vL,vsmbM,st 11.., Lord Rosse-sev dark 1 M 3 GLOCL CVN 1342.2 +2822 7:11 14:46 22:20 6.3 18.0' marks within 5' of center 2 M 5 GLOCL SER 1518.5 +0205 10:17 16:22 22:27 5.7 23.0' NGC 5904, !!,vB,L,eCM,eRi, st mags 11...;superb cluster M 94 GALXY CVN 1250.9 +4107 5:12 13:55 22:37 8.1 14.4'x12.1' NGC 4736, vB,L,iR,vsvmbM,BN,r NGC 6121, Cl,8 or 10 B* in line,rrr, Look for central bar M 4 GLOCL SCO 1623.6 -2631 12:56 17:27 21:58 5.4 36.0' structure M 80 GLOCL SCO 1617.0 -2258 12:36 17:21 22:06 7.3 10.0' NGC 6093, st 14..., Extremely rich and compressed M 62 GLOCL OPH 1701.2 -3006 13:49 18:05 22:21 6.4 15.0' NGC 6266, vB,L,gmbM,rrr, Asymmetrical M 19 GLOCL OPH 1702.6 -2615 13:34 18:06 22:38 6.8 17.0' NGC 6273, vB,L,R,vCM,rrr, One of the most oblate GC 3 M 107 GLOCL OPH 1632.5 -1303 12:17 17:36 22:55 7.8 13.0' NGC 6171, L,vRi,vmC,R,rrr, H VI 40 M 106 GALXY CVN 1218.9 +4718 3:46 13:23 22:59 8.3 18.6'x7.2' NGC 4258, !,vB,vL,vmE0,sbMBN, H V 43 M 63 GALXY CVN 1315.8 +4201 5:31 14:19 23:08 8.5 12.6'x7.2' NGC 5055, BN, vsvB stell. -

Feb BACK BAY 2019

Feb BACK BAY 2019 The official newsletter of the Back Bay Amateur Astronomers CONTENTS COMING UP Gamma Burst 2 Feb 7 BBAA Meeting Eclipse Collage 3 7:30-9PM TCC, Virginia Beach NSN Article 6 Heart Nebula 7 Feb 8 Silent Sky Club meeting 10 10-11PM Little Theatre of VB Winter DSOs 11 Contact info 16 Feb 8 Cornwatch Photo by Chuck Jagow Canon 60Da, various exposures, iOptron mount with an Orion 80ED Calendar 17 dusk-dawn The best 9 out of 3465 images taken from about 10:00 PM on the 20th Cornland Park through 2:20 AM on the 21st. Unprocessed images (only cropped). Feb 14 Garden Stars 7-8:30PM LOOKING UP! a message from the president Norfolk Botanical Gardens This month’s most talked about astronomy event has to be the total lunar Feb 16 Saturday Sun-day eclipse. The BBAA participated by supporting the Watch Party at the 10AM-1PM Chesapeake Planetarium. Anyone in attendance will tell you it was COLD, but Elizabeth River Park manageable if you wore layers, utilized the planetarium where Dr. Robert Hitt seemed to have the thermostat set to 100 degrees, and drank copious amounts Feb 23 Skywatch of the hot coffee that Kent Blackwell brewed in the back office. 6PM-10PM The event had a huge following on Facebook but with the cold Northwest River Park temperatures, we weren’t sure how many would come out. By Kent’s estimate there were between 100–200 people in attendance. Many club members set up telescopes, as well as a few members of the public too. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Star Clusters

Star Clusters Culpeper Astronomy Club (CAC) Meeting May 21, 2018 Overview • Introductions • Main Topic: Star Clusters - Open and Globular • Constellations: Bootes, Canes Venatici, Coma Berenices • Observing Session - TBD Observing Session – 29 April 18 • Kicked off at about 6:30 p.m • Ended at about 1:30 a.m • Set up several telescopes • Three refractor’s (RAS -7”, f/12) • 11” CPC 1100 SCT (Dennis) • 12” Meade SCT • Targets included: • Venus • Moon • Several double stars • Several deep sky objects • Jupiter • Checked out Saturn and Mars at after arriving home – 2:30 a.m. Loaner Telescopes Jupiter near Opposition • Taken on 13 May 2018 by Jerry Sykes (Opposition 8 May) • Taken with a 120mm refractor, 3x barlow and ASI224mc video camera • First time using his ASI224mc camera • Took several videos through breaks in the clouds • Shot 21,700 frames in a little over two minutes. • Used 29% of 21,700 frames • Captured using Sharpcap • Stacked in AS!3 • Processed in Registax6 Stellar Evolution - The Birth • Stars are born within the clouds of dust and gas scattered throughout most galaxies (Orion Nebula) • Swirling cloud gives rise to knots with sufficient mass that the gas and dust can begin to collapse under its own gravitational attraction • As cloud collapses, material at the center heats up and begins gathering dust and gas (Protostar) • Spinning clouds may break up into two or three blobs resulting in paired or groups of multiple stars • Not all of this material ends up as part of a star — the remaining dust can become planets, asteroids, -

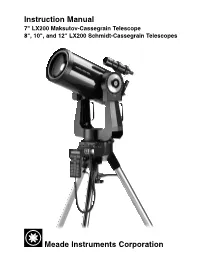

Instruction Manual Meade Instruments Corporation

Instruction Manual 7" LX200 Maksutov-Cassegrain Telescope 8", 10", and 12" LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescopes Meade Instruments Corporation NOTE: Instructions for the use of optional accessories are not included in this manual. For details in this regard, see the Meade General Catalog. (2) (1) (1) (2) Ray (2) 1/2° Ray (1) 8.218" (2) 8.016" (1) 8.0" Secondary 8.0" Mirror Focal Plane Secondary Primary Baffle Tube Baffle Field Stops Correcting Primary Mirror Plate The Meade Schmidt-Cassegrain Optical System (Diagram not to scale) In the Schmidt-Cassegrain design of the Meade 8", 10", and 12" models, light enters from the right, passes through a thin lens with 2-sided aspheric correction (“correcting plate”), proceeds to a spherical primary mirror, and then to a convex aspheric secondary mirror. The convex secondary mirror multiplies the effective focal length of the primary mirror and results in a focus at the focal plane, with light passing through a central perforation in the primary mirror. The 8", 10", and 12" models include oversize 8.25", 10.375" and 12.375" primary mirrors, respectively, yielding fully illuminated fields- of-view significantly wider than is possible with standard-size primary mirrors. Note that light ray (2) in the figure would be lost entirely, except for the oversize primary. It is this phenomenon which results in Meade 8", 10", and 12" Schmidt-Cassegrains having off-axis field illuminations 10% greater, aperture-for-aperture, than other Schmidt-Cassegrains utilizing standard-size primary mirrors. The optical design of the 4" Model 2045D is almost identical but does not include an oversize primary, since the effect in this case is small.