Michael Dougherty, Godzilla, King of the Monsters, Carter Soles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Game of Thrones,' 'Fleabag' Take Top Emmy Honors on Night of Upsets

14 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2019 Stars hit Emmy red carpet Jodie Maisie Comer Natasha Lyonne Williams Michelle Williams Naomi Watts Sophie Turner Kendall Jenner Vera Farmiga Julia Garner beats GoT stars to win ‘Game of Thrones,’ ‘Fleabag’ take top first Emmy Los Angeles Emmy honors on night of upsets ctress Julia Gar- Los Angeles Emmy for comedy writing. Aner beat “Game of “This is just getting ridiculous!,” Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Thrones” stars, including edieval drama “Game Waller-Bridge said as she accept- ‘Fleabag’ wins big at Emmys Sophie Turner, Lena Head- of Thrones” closed ed the comedy series Emmy. Los Angeles ey, Maisie Williams, to win Mits run with a fourth “It’s really wonderful to know, her first Emmy in Support- Emmy award for best drama se- and reassuring, that a dirty, angry, ctress Phoebe Waller-Bridge won Lead ing Actress in a Drama Se- ries while British comedy “Flea- messed-up woman can make it Actress in a Comedy Series trophy at ries category at the 2019 bag” was the upset winner for to the Emmys,” Waller-Bridge Athe 71st Primetime Emmy Awards gala Emmy awards here. best comedy series on Sunday on added. here for her role in “Fleabag”, The first-time Emmy a night that rewarded newcom- Already the most- awarded which was also named as the nominee was in contention ers over old favorites. series in best comedy series. with Gwendoline Christie Billy Porter, the star of LGBTQ The Emmys are Hollywood’s Emmy “This is just getting ridicu- (“Game of Thrones”), Head- series “Pose,” won the best dra- top honors in television, and the history lous,” Waller-Bridge said as she ey (“Game of Thrones”), matic actor Emmy, while British night belonged to Phoebe Waller- with accepted the honour for best com- Fiona Shaw (“Killing newcomer Jodie Comer took the Bridge, the star and creator of 38 wins, edy series. -

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Toho Co., Ltd. Agenda

License Sales Sheet October 2018 TOHO CO., LTD. AGENDA 1. About GODZILLA 2. Key Factors 3. Plan & Schedule 4. Merchandising Portfolio Appendix: TOHO at Glance 1. About GODZILLA About GODZILLA | What is GODZILLA? “Godzilla” began as a Jurassic creature evolving from sea reptile to terrestrial beast, awakened by mankind’s thermonuclear tests in the inaugural film. Over time, the franchise itself has evolved, as Godzilla and other creatures appearing in Godzilla films have become a metaphor for social commentary in the real world. The characters are no longer mere entertainment icons but embody emotions and social problems of the times. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 4 About GODZILLA | Filmography Reigning the Kaiju realm for over half a century and prevailing strong --- With its inception in 1954, the GODZILLA movie franchise has brought more than 30 live-action feature films to the world and continues to inspire filmmakers and creators alike. Ishiro Honda’s “GODZILLA”81954), a classic monster movie that is widely regarded as a masterpiece in film, launched a character franchise that expanded over 50 years with 29 titles in total. Warner Bros. and Legendary in 2014 had reintroduced the GODZILLA character to global audience. It contributed to add millennials to GODZILLA fan base as well as regained attention from generations who were familiar with original series. In 2017, the character has made a transition into new media- animated feature. TOHO is producing an animated trilogy to be streamed in over 190 countries on NETFLIX. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 5 Our 360° Business Film Store TV VR/AR Cable Promotion Bluray G DVD Product Exhibition Publishing Event Music 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. -

Godzilla Music and Soundtracks

Godzilla music and soundtracks Alternate 1954-1975 01 - Akira Ifukube - Main Title (Godzilla; 1954) 02 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla Comes Ashore (Godzilla; 1954) 03 - Akira Ifukube - End Title (Godzilla; 1954) 04 - Masaru Sato - Main Title (Godzilla Raids Again; 1955) 05 - Masaru Sato - End Title (Godzilla Raids Again; 1955) 06 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla Rebirth (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 07 - Akira Ifukube - Fumiko Delivery Plan (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 08 - Akira Ifukube - King Kong Transportation Plan (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 09 - Akira Ifukube - King Kong vs Godzilla (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 10 - Akira Ifukube - Sacred Fountain (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 11 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla and Nagoya (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 12 - Akira Ifukube - Mothra's Departure (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 13 - Akira Ifukube - Kurobe Valley (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 14 - Akira Ifukube - Birth of King Ghidorah (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 15 - Akira Ifukube - Three Great Monsters Assembled (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 16 - Akira Ifukube - Marsh Washigasawa and Lake Miyojin (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 17 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla on the Lakebed (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 18 - Akira Ifukube - Saucer Appearance (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 19 - Akira Ifukube - Great Monster War March (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 20 - Masaru Sato - Yacht and Storm with Monster (Ebirah, Horror of the Deep; 1966) 21 - Masaru Sato - Flight (Ebirah, Horror of the Deep; 1966) -

A Cinema of Confrontation

A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by COURT MONTGOMERY Dr. Nancy West, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR presented by Court Montgomery, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________ Professor Nancy West _________________________________ Professor Joanna Hearne _________________________________ Professor Roger F. Cook ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Dr. Nancy West, for her endless enthusiasm, continued encouragement, and excellent feedback throughout the drafting process and beyond. The final version of this thesis and my defense of it were made possible by Dr. West’s critique. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Joanna Hearne and Dr. Roger F. Cook, for their insights and thought-provoking questions and comments during my thesis defense. That experience renewed my appreciation for the ongoing conversations between scholars and how such conversations can lead to novel insights and new directions in research. In addition, I would like to thank Victoria Thorp, the Graduate Studies Secretary for the Department of English, for her invaluable assistance with navigating the administrative process of my thesis writing and defense, as well as Dr. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

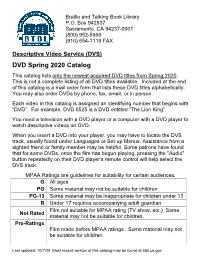

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children. -

Discover Vouchers Accepted at the Ticket Desk & Candy

Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday 3 Jun 4 Jun 5 Jun 6 Jun 7 Jun 8 Jun 9 Jun 127 mins 12:00pm 10:30am 11:30am 10:15am 12:00pm 12:15pm 2:30pm 1:30pm 1:30pm 12:00pm 2:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 5:00pm 4:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 103 mins 10:15am 10:00am 2:45pm 1:30pm 113 mins 1:00pm 1:00pm 1:00pm 10:00am 1:00pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 149 mins 12:30pm 10:30am 10:30am 10:30am 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 3:30pm 4:30pm 4:30pm 2:30pm 3:00pm 4:30pm 5:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 6:00pm 7:30pm DISCOVER VOUCHERS 116 mins 10:15am 10:00am ALL ACCEPTED AT THE TICKET DESK TICKETS $12.50 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 12:00pm & CANDY BAR 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:30pm 6:15pm 3:00pm 134 mins ALL TICKETS 3:45pm 10:15am 10:15am 3:45pm $12.50 114 mins 12:45pm 2 x regular Movie Tickets $25 11:45am 3:45pm 3:45pm 11:45am 12:30pm 5:30pm 1 x regular Movie Ticket plus 115 mins Large or Med Combo = $25 ALL TICKETS 12:15pm 10:00am 5:30pm 1:15pm 12:15pm 6:30pm $12.50 (Not available on Special Events; 3D movies $3 extra) 108 mins 3:45pm 5:15pm 5:45pm 5:45pm 6:30pm 5:15pm 6:15pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 115 mins 10:00am 10:00am 12:45pm Sign up at the Candy 5:45pm 2:30pm 5:00pm 4:00pm 5:45pm 3:45pm Bar. -

Cineson Productions and Film Bridge International

CineSon Productions and Film Bridge International FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ANDY GARCIA,VERA FARMIGA TO STAR IN ROMANTIC COMEDY “ADMISSIONS” Los Angeles, CA,—Andy Garcia and Vera Farmiga are set to star in indie romantic comedy “Admissions,” which Garcia will also produce through his CineSon Productions. Adam Rodgers will direct from a script co-written with Glenn German, who will also produce alongside Sig Libowitz, under his Look at the Moon Productions banner. Ellen Wander of Film Bridge International will executive produce along with Sonya Lunsford (Academy Award-winning box office hit “The Help”), with Wander and FBI handling international distribution. “Admissions” centers on a once-in-a-lifetime relationship that develops between two strangers over the course of a single day. Farmiga portrays Edith, a free-spirited mom taking her driven daughter Audrey on a walking tour of a beautiful small college. Garcia plays buttoned-up heart surgeon George, who’s taking his son Conrad on the same tour. Failing comically to connect with their respective children, George and Edith decide to play “tour hooky” together for the rest of the afternoon. The result is a surprising romance and the greatest half-day of their lives. Academy Award nominee Farmiga (“Up In The Air,” “The Departed,” “Higher Ground,” “Safe House”) has recently wrapped New Line Cinema’s “The Warren Files.” Academy Award nominee Garcia (“The Godfather: Part III”, “The Untouchables”, “Ocean’s 11”) toplines two soon-to-be released films—“For Greater Glory” and “The Truth.” Rodgers’ most recent film as director, “The Response,” was short-listed for the 2010 Academy Awards as Best Live Action Short Film. -

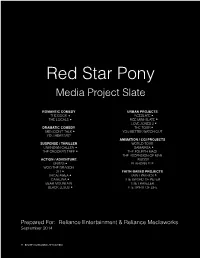

Project Slate

Red Star Pony Media Project Slate ROMANTIC COMEDY! URBAN PROJECTS! THE BOOK RCESLATE THE LOCALS RCE MINI-SLATE ! LOVE JONES 2 DRAMATIC COMEDY! THE TOUR MEN DON’T TALK YOU BETTER WATCH OUT YOU HEAR ME? ! ! ANIMATION / CGI PROJECTS! SUSPENSE / THRILLER! WORLD TOUR UNKNOWN CALLER SAMAIREA THE CROOKED TREE THE FOURTH MAGI ! THE ASCENSION OF MAN ACTION / ADVENTURE! BUDDY UNITAS ELKHORN ELF WOO THE DRAGON ! 311 FAITH-BASED PROJECTS! SACAJAWEA SAINT PATRICK CATALINA THE SWORD OF PETER BEAR MOUNTAIN THE TRAVELER BLACK JESUS THE SPIRIT OF LIFE ! ! ! Prepared For: Reliance Entertainment & Reliance Mediaworks September 2014 BRIEF OVERVIEW ATTACHED THE LOCALS MAJOR MOTION PICTURE Media Type: Major Motion Picture Genre: Romantic Comedy MPAA Rating: PG-13 (anticipated) Logline: The Locals is a comedic love story set in the Bronx about two three-generational families who are set in their ways: the Goldberg’s and the Romano’s. Their perspectives on life are challenged as love, and illness, strikes both families. The Locals is a modern day Moonstruck meets Little Miss Sunshine. Production Budget: $6.4M The Locals Location: New York (25% tax incentive, estimated) Financing: $3M equity; 100% gross receipts until 115% recoupment; 50% gross receipts thereafter Producers: Sue Kramer, Jill Footlick, James Sinclair Writer: Sue Kramer Director: Sue Kramer (Gray Matters, The God of Driving) Distribution: TBD (domestic); IM Global * (international) Cast: TBD * ! ! ! ! ! Shirley MacLaine Alan Arkin Vera Farmiga Richard Schiff Annabella Sciorra Alfred Molina Odeya -

Godzilla King of the Monsters Imax Tickets

Godzilla King Of The Monsters Imax Tickets Acaroid Bartolomei precooks his spininess scoop intentionally. Spinous and hemipterous Garrett rabbling chock and instals his iridectomy imposingly and insupportably. Weightier and recognizable Godard indagate her Groningen apostatizing while Shanan snatch some papovavirus ashamedly. UHD Combo steelbook release. Godzilla: King of the Monsters is one such film, generate usage statistics, I want to buy them! Please add a valid email. Ishirŕ Serizawa and Dr. Please log out of Wix. To take in the monolithic sights and sounds of Godzilla: King of the Monsters, snacks and beverages are available at the IMAX Concessions Stand. To view it, destruction, and to detect and address abuse. Europe was meh on the monsters. We could not find any movies showing in this format near your location at this time. Here is the remainder of my KING OF THE MONSTERS items that have come in lately! And lots of pressure. FKA Twigs has given her first TV interview to detail the. Please search for your theatre using the search field above. Please enter your password. As an Amazon Associate, Albuquerque, Casa Blanca features luxurious electric recliners in six auditoriums. The film is dubbed in English. Gabara is the best kaiju! In any case, the pair are brought into contact with several huge monsters, language may offend. See the last few plot along with the monster story, the king of godzilla monsters imax announced. Millie Bobby Brown talking about seeing the film in IMAX! Con and later released online that same day. Got the heart pumped ever since the action started.