The Program RACHMANINOFF Daisies, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

August 2012 Calendar of Events

AUGUST 2012 CALENDAR OF EVENTS For complete up-to-date information on the campus-wide performance schedule, visit www.LincolnCenter.org. Calendar information LINCOLN CENTER THEATER LINCOLN CENTER LINCOLN CENTER is current as of War Horse OUT OF DOORS OUT OF DOORS Based on a novel by Brandt Brauer Frick Ensemble Phil Kline: dreamcitynine June 25, 2012 Michael Morpurgo (U.S. debut) performed by Talujon Adapted by Nick Stafford Damrosch Park 7:30 PM Sixty percussionists throughout August 1 Wednesday In association with Handspring the Plaza perform a live version of LINCOLN CENTER FILM SOCIETY OF Puppet Company Phil Kline’s GPS-based homage to Vivian Beaumont Theater 2 & 8 PM OUT OF DOORS John Cage’s Indeterminacy. LINCOLN CENTER Josie Robertson Plaza 6:30 PM To view the Film Society's On Sacred Ground: August schedule, visit LINCOLN CENTER PRESENTS Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring LINCOLN CENTER www.filmlinc.com MOSTLY MOZART FESTIVAL Arranged and Performed by OUT OF DOORS Mostly Mozart The Bad Plus LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL Damrosch Park 8:30 PM Chio-Tian Folk Drums and Festival Orchestra: Arts Group (U.S. debut) In Paris: Opening Night LINCOLN CENTER THEATER Hearst Plaza 7:30 PM Dmitry Krymov Laboratory Louis Langrée, conductor War Horse Dmitry Krymov, direction Nelson Freire, piano LINCOLN CENTER Based on a novel by and adaption Lawrence Brownlee, tenor OUT OF DOORS With Mikhail Baryshnikov, (Mostly Mozart debut) Michael Morpurgo Kimmo Pohjonen & Anna Sinyakina, Maxim All-Mozart program: Adapted by Nick Stafford Helsinki Nelson: Maminov, Maria Gulik, Overture to La clemenza di Tito In association with Handspring Accordion Wrestling Dmitry Volkov, Polina Butko, Piano Concerto No. -

Current Professional Affiliations Are Listed Below Each Player's Name

Peter McGuire Jessica Guideri Minnesota Orchestra Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, Gustavus Adolphus College, faculty Associate Concertmaster Eastern Music Festival, Associate Kurt Nikkanen Concertmaster New York City Ballet Orchestra, Concertmaster Jonathan Magness Minnesota Orchestra, Associate Leonid Sigal Principal Second Violin Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Bravo Music Festival, faculty Concertmaster University of Hartford, faculty Yevgenia Strenger Current professional affiliations are The Hartt School, faculty New York City Opera, Concertmaster listed below each player’s name. ( ) = previous affiliation. Eric Wyrick Na Sun New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Concertmaster First Violins Orpheus Chamber Orchestra Alisa Wyrick Bard Music Festival New York City Opera Orchestra David Kim - Concertmaster The Philadelphia Orchestra, Elizabeth Zeltser Concertmaster New York Philharmonic Violas University of Texas at Austin, faculty Yulia Ziskel Rebecca Young - Principal Jeffrey Multer New York Philharmonic New York Philharmonic, Associate The Florida Orchestra, (New Jersey Symphony) Principal Concertmaster Host of the NY Philharmonic Very Eastern Music Festival, Young People's Concerts Concertmaster Second Violins Robert Rinehart Emanuelle Boisvert Marc Ginsberg - Principal New York Philharmonic Dallas Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Principal Ridge String Quartet Associate Concertmaster Second Violin The Curtis Institute, faculty (Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Concertmaster) Kimberly Fisher – Co-Principal Danielle -

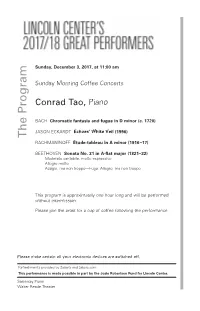

T H E P Ro G

Sunday, December 3, 2017, at 11:00 am m a Sunday Morning Coffee Concerts r g o r Conrad Tao, Piano P BACH Chromatic fantasia and fugue in D minor (c. 1720) e h JASON ECKARDT Echoes’ White Veil (1996) T RACHMANINOFF Étude-tableau in A minor (191 6–17) BEETHOVEN Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major (1821 –22) Moderato cantabile, molto espressivo Allegro molto Adagio, ma non troppo—Fuga: Allegro, ma non troppo This program is approximately one hour long and will be performed without intermission. Please join the artist for a cup of coffee following the performance. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Refreshments provided by Zabar’s and zabars.com This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Walter Reade Theater Great Performers Support is provided by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center. Public support is provided by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund. Endowment support is also provided by UBS. American Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Center Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center UPCOMING GREAT PERFORMERS EVENTS: Wednesday, December 6 at 7:30 pm in Alice Tully Hall Bach Collegium Japan Masaaki Suzuki, conductor Sherezade Panthaki, soprano Jay Carter, countertenor Zachary Wilder, tenor Dominik Wörner, bass BACH: Four Cantatas from Weihnachts-Oratorium (“Christmas Oratorio”) Pre-concert lecture by Michael Marissen at 6:15 pm in the Stanley H. -

Classical Jazz

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER May 29, 2003, 8:00 p.m. on PBS Marsalis at the Penthouse In the summer of 1987 a "Classical Jazz" concert series was established at New York City's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, under the inspired leadership of trumpet player, Wynton Marsalis. Seven years later this indispensable activity was redefined and became the autonomous jazz division at Lincoln Center--Jazz at Lincoln Center. Thus this essential American musical form took its place at Lincoln Center alongside such other constituents as the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera, with Marsalis continuing as the driving force behind it. We have been privileged over the years on Live From Lincoln Center to be able to bring you several performances by this outstanding ensemble, most recently in concert with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic. (Interestingly, during the years of the Masur family's residence in New York, the Maestro's son-- himself an aspiring conductor--became a great jazz enthusiast.) Our next Live From Lincoln Center telecast, on Thursday evening, May 29, will be devoted to yet another live performance by Jazz at Lincoln Center. But with a difference! Our previous sessions with Jazz at Lincoln Center have originated in one of the several concert halls in the Lincoln Center complex and have featured the artistry of the large ensemble. On May 29 the 90-minute performance will take place in the intimate confines of the Kaplan Penthouse high atop the building that houses Lincoln Center's administration offices. The Kaplan Penthouse has served as the locale for three previous Live From Lincoln Center telecasts: two featuring Itzhak Perlman, the other spotlighting Renée Fleming. -

December 2011: Primetime Alaskapublic.Org

schedule available online: December 2011: Primetime alaskapublic.org 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:3010:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 Conversations: Bad Blood: A Cautionary Thu 12/1 This Old House Hour Charlie Rose Tavis Smiley Tavis Smiley Teen Suicide in Alaska Tale Washington Alaska PBS Arts From New York: Fri 12/2 Need to Know Charlie Rose Week Edition Great Performances Andrea Bocelli Live in Central Park Victor Borge Sat 12/3 Suze Orman's Money Class 60's Pop, Rock & Soul Victor Borge (start 6pm) Celtic Woman - Believe (start Sun 12/4 Lucille Ball: Finding Lucy An "American Masters" Special Rick Steves' European Christmas 6pm) Mon 12/5 Alone In The Wilderness, Part Two American Family: Anniversary Edition Charlie Rose Alaska Far Away: The New Deal Pioneers of the Matanuska Tue 12/6 Celtic Woman - Believe Charlie Rose Colony Wed 12/7 Suze Orman's Money Class Journey Of The Universe Victor Borge Charlie Rose 3 Steps To Incredible Health! With Joel Great Performances: Jackie How To Shop For Free With Thu 12/8 Charlie Rose Fuhrman, M.D. Evancho: Dream With Me In Concert Coupon Master Kathy Spencer Washington Alaska Human Nature Sings Motown With Special Fri 12/9 Need to Know Roy Orbison: In Dreams Charlie Rose Week Edition Guest Smokey Robinson Alaska Far Away Santana - Live At Montreux Sat 12/10 Alone In The Wilderness, Part Two Paul Simon: Live In Webster Hall, New York (start 6pm) 2011 Alone Great Performances: Jackie Sun 12/11 60's Pop, Rock & Soul Buddy Holly: Listen To Me (start 6pm) Evancho: Dream With Me In Concert Antiques Roadshow: B.E. -

Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 11-3-2017 Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival" (2017). Music Department Concert Programs. 505. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/505 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LJ --w ...~ r~ S+ if! L Christopher Chandler Acting Director WELCOME to the 2017 Third festival presents works by students Practice Electroacoustic Music Festi from schools including the University val at the University of Richmond. The of Mary Washington, University of festival continues to present a wide Richmond, University of Virginia, variety of music with technology; this Virginia Commonwealth University, year's festival includes works for tra and Virginia Tech. ditional instruments, glass harmon Festivals are collaborative affairs ica, chin, pipa, laptop orchestra, fixed that draw on the hard work, assis media, live electronics, and motion tance, and commitment of many. sensors. We are delighted to present I would like to thank my students Eighth Blackbird as ensemble-in and colleagues in the Department residence and trumpeter Sam Wells of Music for their engagement, dedi as our featured guest artist. cation, and support; the staff of the Third Practice is dedicated not Modlin Center for the Arts for their only to the promotion and creation energy, time, and encouragement; of new electroacoustic music but and the Cultural Affairs Committee also to strengthening ties within and the Music Department for finan our community. -

The Black Clown

Wednesday–Saturday, July 24–27, 2019 at 7:30 pm Post-performance talk with Davóne Tines, Zack Winokur, and Chanel DaSilva on Thursday, July 25 NEW YORK PREMIERE The Black Clown Adapted from the Langston Hughes poem by Davóne Tines & Michael Schachter Music by Michael Schachter Directed by Zack Winokur A production of American Repertory Theater at Harvard University With the kind cooperation of the Estate of Langston Hughes Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Major endowment support for contemporary dance and theater is provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College Mostly Mozart Festival American Express is the lead sponsor of the Mostly Mozart Festival Major endowment support for contemporary dance and theater is provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Additional endowment support is provided by the Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance, Nancy Abeles Marks and Jennie L. and Richard K. DeScherer The Mostly Mozart Festival is also made possible by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser. Additional support is provided by The Shubert Foundation, LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, Howard Gilman Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc., The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.), Inc, Harkness Foundation for Dance, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Spotlight, Chairman’s Council, Friends of Mostly Mozart, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. -

6AM Wild Kratts 6AM Mr. Rogers 6AM Wealth Track with Consuelo Mack

WEEKDAYS SATURDAYS SUNDAYS 6AM Wild Kratts 6AM Mr. Rogers 6AM Wealth Track With Consuelo Mack 6:30 Cat In The Hat 6:30 Dinosaur Train 6:30 Motorweek 7AM Ready, Jet Go! 7AM Bob The Builder 7AM Sesame Street 7:30 Wild Kratts 7:30 Daniel Tiger's 7:30 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 8AM Curious George 8AM Pinkalicious 8AM Pinkalicious 8:30 Curious George 8:30 Woodsmith Shop 8:30 Splash & Bubbles 9AM Pinkalicious 9AM Woodwright's Shop 9AM Curious George 9:30 Daniel Tiger's 9:30 This Old House 9:30 Nature Cat 10AM Daniel Tiger's 10AM Ask This Old House 10AM NOVA 10:30 Splash & Bubbles 10:30 Rick Steves' Europe 11AM NATURE 11AM Sesame Street 11AM 6-May Noon Masterpiece: Endeavour Season 4 Antiques Roadshow 11:30 Super Why 11:30 3PM Little Women, A Timeless Story NOO Dinosaur Train NOO 3:30 Masterpiece: Downton Abbey Great British Baking Show 12:30 Peg & Cat 12:30 5PM Weekend With Yankee 1PM Sesame Street 1PM Simply Ming 5:30 PBS Newshour Weekend 1:30 Splash & Bubbles 1:30 Lidia's Kitchen 6PM Father Brown 2PM Curious George 2PM Plates & Places 7PM Crimson Field 2:30 Pinkalicious 2:30 Martha Bakes 13-May Noon Masterpiece: Endeavour Season 4 3PM Nature Cat 3PM America's Test Kitchen 3PM Masterpiece: Downton Abbey 3:30 Wild Kratts 3:30 New Orleans Kitchen 5PM Weekend With Yankee 4PM Wild Kratts 4PM British Antiques Roadshow 5:30 PBS Newshour Weekend 4:30 Odd Squad 4:30 6PM Father Brown Lawrence Welk 5PM Odd Squad 5PM 7PM Little Women, A Timeless Story 5:30 Arthur 5:30 PBS News Weekend 7:30 Orchard House: The Home Of Little Women 6PM BBC World News America 6PM Doctor Blake Mysteries 20-May Noon GP at the Met: La Boheme 6:30 7PM Midsomer Murder 2:30 Opera Reimagened PBS Newshour 7PM 3PM Masterpiece: Downton Abbey 7:30 Various/British Antiques 5PM Weekend With Yankee Roadshow 5:30 PBS Newshour Weekend 6PM Father Brown Exceptions: 7PM Mark Twain's Journey To Jerusalem Mon. -

APRIL 2018 PRIME TIME SCHEDULE Subject to Change Without Notice

APRIL 2018 PRIME TIME SCHEDULE Subject to change without notice. Please check local listings. Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 5:30 Downton Abbey 7:00 Antiques Roadshow 7:00 Roads to Memphis: 7:00 Nature: Sex, Lies & 7:00 Daytripper 7:00 Washington Week 7:00 70s Soul Superstars 7:00 Call the Midwife 8:00 Antiques Roadshow American Experience Butterflies 7:30 Two For The Road: 7:30 Metoo, Now What? 9:30 Songs at the Center 8:00 Soundbreaking: Going Electric 8:00 The Child in Time on 9:00 Independent Lens: 8:00 Black America Since 8:00 Black America Since Canadian Arctic 10:00 Austin City Limits: Masterpiece MLK: And Still I Rise MLK: Keep Your Head Up 9:00 Soundbreaking: When God Sleeps 8:00 The Tunnel: Sabotage Four on the Floor Cyndi Lauper 9:30 Little Women: 10:00 Amanpour on PBS 10:00 Amanpour on PBS 9:00 Antiques Roadshow A Timeless Story 10:30 Amanpour on PBS 10:00 Soundbreaking: 11:00 Bluegrass Underground 10:30 Beyond 100 Days 10:30 Beyond 100 Days 10:00 Amanpour on PBS The World is Yours 10:00 Ribbon of Sand 11:00 Newsline 11:30 Live at the Charleston 11:00 Newsline 11:00 Newsline 10:30 Beyond 100 Days 11:00 Newsline Music Hall: Edwin McCain 10:30 On Story 11:30 Stories from the Stage 11:30 BBC World News 11:30 Stories from the Stage 11:00 Newsline 11:00 Globe Trekker: Hawaii 11:30 Stories from the Stage 11:30 Stories from the Stage 1 2 3 4 11:30 Stories from the Stage 5 6 7 5:30 Downton Abbey 7:00 Antiques Roadshow 7:00 Secrets of the Dead: 7:00 NATURE: Moose: 7:00 Daytripper 7:00 Washington Week 7:00 -

Live from Lincoln Center President's Letter The

The Moving Image Live From Lincoln Center: Upcoming Special Events Live From Lincoln Center Upcoming Telecasts Thursday, October 22, 2015 Lincoln Center 2015 Fall Gala Nothing is more kinetic season, indeed no December, would be complete without The Friday, October 16, 2015 Honoring Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee the newsletter of lincoln center for the performing arts Autumn 2015 than dance. And no Nutcracker. The first season of Lincoln Center at the Movies Kern & Hammerstein’s Show Boat with the Distinguished Service Award medium is better wraps up December 5 and 10, with George Balanchine’s in Concert with the New York Philharmonic Alice Tully Hall suited to capture a iconic and beloved version of the holiday classic set to PBS Arts Fall Festival Lincoln Center’s Fall Gala celebrates the opening of the 2015- President’s Letter dancer’s every move Tchaikovsky’s masterful score. Conducted and directed for the stage by Ted Sperling, the 2016 performance seasons and raises crucial funding to than film. So it was New York Philharmonic production of the groundbreaking “Although New Yorkers may not know this, San Francisco is support a diverse range of Lincoln Center’s programs. This natural for Lincoln musical features an all-star cast led by Vanessa Williams and the oldest ballet company in the country, with many American year’s honorees are longstanding supporters of Lincoln Center Center to launch an Downton Abbey’s Julian Ovenden, with Norm Lewis, Jane firsts in its history, including the first Nutcracker and the first and the arts in New York City: Thomas H.