When Ngos Fulfill State Obligations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marriage Book Index, 1837-1920 Lake County, Indiana

Marriage Book Index, 1837‐1920 Lake County, Indiana This index was developed from marriage license books located in Lake County, Indiana, spanning 1837 to 1920. Both groom and bride indexes will provide the following information: the book number, page number, a license number, application number, groom and bride’s name, age (if given), a second spelling (if given), and the marrying official. We have added the church name (if given) in the notes columns and whether there was consent by a parent or nearest relative. Requests for copies of the original marriage application and license can be made by contacting the Lake County, Indiana, Clerk’s Office using the form at the following website (Note that the Clerk's Office asks that you send no more than three requests at one time): http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~innwigs/Archives/MarriageLicCopies.pdf © 2009 ‐ Northwest Indiana Genealogical Society Northwest Indiana Genealogical Society Marriage Book Index, 1837-1920 Brides Lake County, Indiana Surname Begins with W Bk# Pg# Lic # Appl Rec Groom's L Name G 2nd Sp Groom's F Name Groom's Age Bride's L Name B 2nd Sp Bride's F Name Bride's Age Appl Date Return Date Marr Date Marrying Official Title Clerk Misc Notes 019 342 021804 043 NEUMANN Louis WAAGE Clara 03/21/1912 03/30/1912 03/21/1912 Atkin, Joseph T. JP Ernest L. Shortridge 015 167 014819 020 BLUME Edward I. WAAGE Ida 08/29/1908 08/31/1908 08/29/1908 Nicholson, H. B. JP Ernest L. Shortridge 013 199 013834H SCARISBRICK Winifield WAAK Caroline S. -

Ministério Da Educação Universidade Federal De Pelotas Cra Sisu 2019/2

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PELOTAS CRA SISU 2019/2 - Lista de Espera (UFPel) Curso: ADMINISTRAÇÃO - Bacharelado/Noturno Classific. Legenda Nome do Candidato Assinatura 1 AC EVELYN FERREIRA LIMA 2 AC VINICIUS BONFIM PACHECO 4 AC GABRIEL PEREIRA DE OLIVEIRA 5 AC JULIA GARCIA ALVES 6 AC CAUY NUNES BATALHA 7 AC ISADORA TRINDADE RODALES 8 L05 ANDRINE BIERHALS NORNBERG 9 L05 ANDRE PINTO GERALDO 10 AC ANDREW LEWS PLAMER AIRES 12 AC BRUNO BERANGER BIER FERREIRA 14 AC RAQUEL SARUBBI TRINDADE 16 L05 VAGNER NUBIAS DE MEDEIROS 17 AC LAZARO ELIZEO LUTZ FERREIRA VILELA 19 AC DAIANA DUARTE BILHARVA 20 L05 THALIA LOPES ANDERSON 22 AC PALOMA VEGE MARTH 23 AC JOSEFER DE LIMA SOUZA 24 L01 RITA DE CASSIA XAVIER VEIGA 25 L05 VINICIUS DE VASCONCELOS LOPES 26 L01 LYANDRA DA CRUZ DE SOUZA 28 AC ALEXANDRE GONCALVES DA ROSA 29 AC LETICIA CALDAS LOPES 31 AC ALINE RIBEIRO BEZERRA DE OLIVEIRA 34 L05 BRUNA COSTA ROSA 36 L05 JOAO PEDRO VASCONCELOS VAZ 38 L05 MARINA DE OLIVEIRA DE MAGALHAES 39 AC ELISA VOLZ GIMENES 40 L05 MARCELO MORALES FONSECA 44 L01 LUCAS PEREIRA PINHEIRO 46 L05 VICTOR DA SILVEIRA MATTOZO 48 AC JOAO PEDRO RODRIGUES RIBEIRO 49 AC JULIA DA CUNHA GAMEIRO 54 AC PEDRO ENRICO SAAD CARVALHO 56 L05 MAIQUELEM DA CRUZ ALVES 57 AC JULIANA DELGADO OLIVERA 58 AC PAULO ROBERTO DA SILVA OLIVEIRA 61 L05 MATHEUS PEREIRA MENEGONI 63 AC GRAZIELE PEGLOW ISNARDI PERES 65 L05 HELENA STORCH DE SOUZA 68 AC ALEXANDER DE ANDRADE CARVALHO 69 L01 LUAN GUILHERME BUBOLZ 70 L01 CALIEL CORONEL 71 L05 THALIA DE MORAES GONCALVES 74 AC MARCIELE CAMARGO DORNELES -

NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY Expenditure Report October 1, 2015

NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY Expenditure Report October 1, 2015 - March 31, 2016 Carl E. Heastie, Speaker . TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................... ix ASSEMBLY MEMBERS ABBATE, PETER J. JR. ............................................ 2 ABINANTI, THOMAS J. ............................................. 4 ARROYO, CARMEN E. ............................................... 6 AUBRY, JEFFRION L. .............................................. 9 BARCLAY, WILLIAM A. ............................................. 11 BARRETT, DIDI D. ................................................ 13 BARRON, CHARLES ................................................. 15 BENEDETTO, MICHAEL R. ........................................... 16 BICHOTTE, RODNEYSE .............................................. 18 BLAKE, MICHAEL A. ............................................... 20 BLANKENBUSH, KENNETH D. ......................................... 22 BORELLI, JOSEPH C. (RESIGNED FROM ASSEMBLY NOVEMBER 23, 2015)... 24 BRABENEC, KARL A. ............................................... 25 BRAUNSTEIN, EDWARD C. ........................................... 27 BRENNAN, JAMES F. ............................................... 30 BRINDISI, ANTHONY J. ............................................ 32 BRONSON, HARRY B. ............................................... 34 BUCHWALD, DAVID E. .............................................. 36 BUTLER, MARC W. ................................................. 38 CAHILL, KEVIN A. ............................................... -

Marriages 1885-1920

Chester County Marriages Grooms Index 1885-1930 Groom's Last Name Groom's First Name Middle Name Groom's Date of Birth Groom's Age Bride's First Name Bride's Last Name Date of Application Date of Marriage Place of Marriage License # Aaron J Ward 18 Leonore Harvey January 2, 1926 Green Hill 26191 Aaron Rowland 21 Ethel Brown January 7, 1925 West Chester 25535 Aaronoff Joseph 27 Kathryn Kann December 2, 1915 Lincoln University 18839 Aaronson JosephFebruary 20, 1871 Rosa Kaplan June 5, 1896 5413 Abbott Charles FApril 8, 1874 Elsie Kurts September 24, 1903 Landenberg 10008 Abbott Charles Shewell 24 Margaret Robinson August 6, 1923 Paoli 24532 Abbott Frank EdwardNovember 7, 1862 Beatrice Andrews December 9, 1891 Coatesville 2931 Abbott GeorgeDecember 9, 1876 Elizabeth Scattergood May 5, 1898 West Chester 6442 Abbott James HermanFebruary 19, 1871 Maud Waitneight January 30, 1901 Phoenixville 8156 Abel Charles Boehnke 21 Mabel Barnes March 27, 1929 Honey Brook 29126 Abel Charles William 23 Cora Peters April 21, 1928 Union Presbyterian Church Manse 28004 Abel Howard JOctober 29, 1875 19 Bertha Martin December 10, 1894 Kennett Square 4532 Abel Howard SamuelNovember 14, 1884 Sara Forest February 17, 1906 Brandywine Manor 11674 Abel Joshua MAugust 9, 1863 Kate Haise April 4, 1889 West Chester 1531 Abel William MAugust 9, 1868 Caroline Rigdon March 23, 1904 West Chester 10308 Abernathy John ASeptember 9, 1886 Emma Hall March 13, 1912 Downingtown 16266 Abernathy Samuel COctober 14, 1874 Ethel Chrisman September 19, 1906 Coventryville 12112 Abernathy -

Marriage Book Index, 1837-1920 Lake County, Indiana

Marriage Book Index, 1837‐1920 Lake County, Indiana This index was developed from marriage license books located in Lake County, Indiana, spanning 1837 to 1920. Both groom and bride indexes will provide the following information: the book number, page number, a license number, application number, groom and bride’s name, age (if given), a second spelling (if given), and the marrying official. We have added the church name (if given) in the notes columns and whether there was consent by a parent or nearest relative. Requests for copies of the original marriage application and license can be made by contacting the Lake County, Indiana, Clerk’s Office using the form at the following website (Note that the Clerk's Office asks that you send no more than three requests at one time): http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~innwigs/Archives/MarriageLicCopies.pdf © 2009 ‐ Northwest Indiana Genealogical Society Northwest Indiana Genealogical Society Marriage Book Index, 1837-1920 Brides Lake County, Indiana Surname Begins with P Bk# Pg# Lic # Appl Rec Groom's L Name G 2nd Sp Groom's F Name Groom's Age Bride's L Name B 2nd Sp Bride's F Name Bride's Age Appl Date Return Date Marr Date Marrying Official Title Clerk Misc Notes 059 421 085452 256 SPISAK Joseph PAA Elsie 06/08/1926 07/01/1926 06/08/1926 Kemp, Howard H. JP John Killigrew 010 094 MAY Daniel J, Jr. 21 PAAPE Minnie 18 02/10/1903 02/20/1903 02/15/1903 Wood, A. W. Min Harold H. Wheeler Hammond 026 129 032422 080 PIERCE LeRoy PAASCH Elsie 09/23/1915 09/28/1915 09/23/1915 Stockbarger, Charles U. -

Exercise Therapy and Cardiac, Autonomic and Systemic Function in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure

Exercise therapy and cardiac, autonomic and systemic function in patients with chronic heart failure Melissa Jane Pearson Bachelor of Exercise & Sports Science (Clinical Exercise Physiology) (Honours, Class 1) A thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Science and Technology University of New England, NSW Australia June 2018 i Declaration I declare that this work has not been and is not being submitted for any other degree to this or any other University. To the best of my knowledge it does not contain any materials previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text; and all substantive contributions by others to the work presented, including jointly authored publications is clearly acknowledged. 20th June 2018 Signed Date ii Acknowledgments To my Principal Supervisor Professor Neil Smart, I would like to acknowledge and express my sincere thanks for your guidance, advice, support, knowledge and patience. Reflecting back to the start of the journey I really wasn’t sure what to expect, however, I can honestly say that I am extremely grateful for the opportunity and experience. It did not go the original way it was planned, but that’s life and all part of the journey. I am taking a lot more away from this journey then I expected. I would also like to thank Associate Professor Gudrun Dieberg for your support, advice and friendship over the years. Most importantly, I would like to acknowledge my husband Warwick. Words cannot fully express how I feel. It was not in our plan for me to undertake such a commitment, but when the opportunity arose you were encouraging and supportive as you always are. -

County of Albany Property Ownership Listing – Street Order

County of Albany Property Ownership Listing – Street Order The information contained in this report is updated through March 1, 2021. We request you report any errors in this report or problems with tax maps for this municipality to the Real Property Tax Service Agency at telephone number 1-518-487-5291 or by e-mail to [email protected]. The Real Property Tax Service Agency is located in Room 1340 of the Harold L. Joyce Office Building, 112 State Street, Albany NY 12207 ISSUED BY THE COUNTY OF ALBANY REAL PROPERTY TAX SERVICE AGENCY – 5/14/2021 City of Watervliet 2021 Street Order Page 1 of 94 Albany County Tax Mapping Program Report: Listowner - TAXM1601 - (By Parcel Address.) R un5/12/2021 Date - SWIS -1800 City of Watervliet Tax Map County Parcel Number Id Num OwnerName Last Known or Reputed Parcel Address 32.50 1 40.000 012 2841 D & H CORPORATION 32.75 1 23.000 0 1300 COUDARI, NICOLE E. & LEECH, SETH R. 12 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 22.000 0 1301 WOOD, DANIEL F 14 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 21.000 0 1302 SHUFELT, CLAYTON W. JR. & VICTORIA M. 16 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 20.000 0 1303 CULIHAN, LINDA 18 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 19.000 0 1304 KEIL, AMANDA J 20 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 18.000 0 1305 LODATO, CHRISTOPHER 22 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 17.000 0 1306 PFOLTZER, GLORIA J 24 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 16.000 0 1307 CAPSTONE GARDEN LLC 26 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 15.000 0 1308 KERBER, DAWN M 28 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.75 1 14.000 0 1309 SMIYH, DOUGLAS W JR & M MICHELLE 30 ANDREWSVILLE CT 32.66 3 21.000 0 2801 HOLMAN, DAWN M. -

Michigan State University Commencement Spring 2021

COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES SPRING 2021 “Go forth with Spartan pride and confdence, and never lose the love for learning and the drive to make a diference that brought you to MSU.” Samuel L. Stanley Jr., M.D. President Michigan State University Photo above: an MSU entrance marker of brick and limestone, displaying our proud history as the nation’s pioneer land-grant university. On this—and other markers—is a band of alternating samara and acorns derived from maple and oak trees commonly found on campus. This pattern is repeated on the University Mace (see page 13). Inside Cover: Pattern of alternating samara and acorns. Michigan State University photos provided by University Communications. ENVIRONMENTAL TABLE OF CONTENTS STEWARDSHIP Mock Diplomas and the COMMENCEMENT Commencement Program Booklet 3-5 Commencement Ceremonies Commencement mock diplomas, 6 The Michigan State University Board of Trustees which are presented to degree 7 Michigan State University Mission Statement candidates at their commencement 8–10 Congratulatory Letters from the President, Provost, and Executive Vice President ceremonies, are 30% post-consumer 11 Michigan State University recycled content. The Commencement 12 Ceremony Lyrics program booklet is 100% post- 13 University Mace consumer recycled content. 14 Academic Attire Caps and Gowns BACCALAUREATE DEGREES Graduating seniors’ caps and gowns 16 Honors and master’s degrees’ caps and 17-20 College of Agriculture and Natural Resources gowns are made of post-consumer 21-22 Residential College in the Arts and Humanities recycled content; each cap and 23-25 College of Arts and Letters gown is made of a minimum of 26-34 The Eli Broad College of Business 23 plastic bottles. -

Bib Startlist Full IM 2907

Last update July 29th, 2021 BIB Age Group Surname First name AWA TriClub Country Represented 831 F18-24 Alen Bo BEL (Belgium) 1 F18-24 Gillespie Hannah GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 442 F18-24 Haugen NiKoline NOR (Norway) 833 F18-24 Hughes Tess GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 444 F18-24 Johansen Karoline FredriKstad TriatlonKlubb NOR (Norway) 1389 F18-24 Martin Hazel GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 446 F18-24 Ryder Becca GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 448 F25-29 ChetVeriKoVa Galina temptraining.ru RUS (Russian Federation) 3 F25-29 Circelli-Rauber Patricia AWA Gold JC Sports Coaching CHE (Switzerland) 1391 F25-29 DaValos Frida MEX (Mexico) 5 F25-29 De la Vega Fer MEX (Mexico) 1393 F25-29 Gonano Carolina ITA (Italy) 450 F25-29 HaaKana Anni FIN (Finland) 507 F25-29 Jaeger Cilia AWA Bronze DEU (Germany) 237 F25-29 Lysons Katie Clapham Chasers GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 835 F25-29 Martin Sheona GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 837 F25-29 OsmanKina Nadiia UKR (Ukraine) 1395 F25-29 Phillimore Paige GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 246 F25-29 Rees Ffion GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 452 F25-29 Sparrow Anna GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 454 F25-29 Webb Tallulah GBR (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) 509 F30-34 Ain el Fitre Nina AWA Bronze Triathlon Club Trigether CHE (Switzerland) 248 F30-34 Arfwidsson Autilia SWE (Sweden) 595 F30-34 Buddell Riin AWA SilVer EST (Estonia) 1397 F30-34 Cafri Noa MYWAY (ISRAEL) ISR (Israel) 239 F30-34 Cardoso Alice AWA Bronze BRA (Brazil) 241 F30-34 Christensen Isabella AWA SilVer DNK (DenmarK) 839 F30-34 Dr. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal Introduction Dickenson, Donna; van Beers, B.C.; Sterckx, S. published in Personalised medicine, individual choice and the common good 2018 DOI (link to publisher) 10.1017/9781108590600.001 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Dickenson, D., van Beers, B. C., & Sterckx, S. (2018). Introduction. In B. van Beers, S. Sterckx, & D. Dickenson (Eds.), Personalised medicine, individual choice and the common good (pp. 1-16). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108590600.001 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 PERSONALISED MEDICINE, INDIVIDUAL CHOICE AND THE COMMON GOOD Hippocrates famously advised doctors, ‘it is far more important to know what person the disease has than what disease the person has’. -

IAAI-Cfis Last Name First Name City State Country Name Aagesen

IAAI-CFIs Last Name First Name City State Country Name Aagesen Thomas Elgin IL UNITED STATES Abbott Tristan Sacramento CA UNITED STATES Abdul RahmanYazeed Singapore Singapore Ablott Ronald Glendora CA UNITED STATES Abma Shawn Louisville KY UNITED STATES Abrams Jeffrey Houston TX UNITED STATES Acors Brian Hanover VA UNITED STATES Acott James Selborne, Alton, HampshireUnited Kingdom Adams Daniel Lawrenceburg TN UNITED STATES Adams David McDonough GA UNITED STATES Adams Ian Las Vegas NV UNITED STATES Adams James Homestead FL UNITED STATES Adams Robert Springfield MA UNITED STATES Adcock Brian Frankfort IL UNITED STATES Adcox Roy Bogalusa LA UNITED STATES Agosti Greg Ridgway PA UNITED STATES Agosti John Wauconda IL UNITED STATES Agosti Michael Volo IL UNITED STATES Ahlgrim Kevin LANCASTER KY UNITED STATES Ahrens Shawn Plainfield IL UNITED STATES Aiken John Fort Ann NY UNITED STATES Alberico Stephen Sioux Falls SD UNITED STATES Alderman Shawn Hurricane WV UNITED STATES Alexander Hurschel Republic MO UNITED STATES Alford Patrick London KY UNITED STATES Alfree Henry Wilmington DE UNITED STATES Aliberti Jessica Cartersville GA UNITED STATES Allen Don Atlanta GA UNITED STATES Allen Kellie Maple Ridge BC Canada Allen Richard Albuquerque NM UNITED STATES Allen Samuel Forest Hill LA UNITED STATES Almon William Columbia TN UNITED STATES Altomare Michael Grove City OH UNITED STATES Alvis D. Curt Ashburn VA UNITED STATES Alwes Brian Kansas City MO UNITED STATES Amann James Cape GirardeauMO UNITED STATES IAAI-CFIs Ammann Robert Williston Park NY UNITED -

Start Wave Race No. Name Surname 1 3454 Rosa Aaronovitch 3 127 Tim

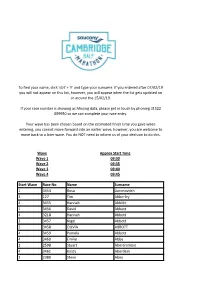

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 07/02/19 you will not appear on this list, however, you will appear when the list gets updated on or around the 15/02/19. If your race number is showing as Missing data, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950 so we can complete your race entry. Your wave has been chosen based on the estimated finish time you gave when entering, you cannot move forward into an earlier wave, however, you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. Wave Approx Start Time Wave 1 09:30 Wave 2 09:35 Wave 3 09:40 Wave 4 09:45 Start Wave Race No. Name Surname 1 3454 Rosa Aaronovitch 3 127 Tim Abberley 4 3455 Hannah Abblitt 1 3456 David Abbott 4 3218 Hannah Abbott 3 3457 Nigel Abbott 2 3458 OLIVIA ABBOTT 4 3459 Pamela Abbott 4 3460 Emilie Abby 2 2598 Stuart Abercrombie 4 3461 Kirsty Aberdein 2 2380 Steve Abey 3 3462 Teresa Ablewhite 3 3463 Alvin Abraham 3 154 Deborah Abraham 2 155 Brett Abram 1 156 Qasim Abul As 3 157 Annalisa Accascina 3 3022 Cosette Ackland 1 3464 Nathan Ackroyd 3 3465 Amanda Acott 2 3466 EVA ACS 3 3467 Anita Adam 2 3468 Rob Adam 1 3469 Benjamin Adams 1 3470 Charles Adams 4 3471 Christine Adams 2 158 Dan Adams 1 3472 David Adams 4 159 Isabel Adams 1 3473 Jonathan Adams 1 160 Matthew Adams 1 3474 Neil Adams 2 3475 Patrick Adams 1 3476 Paul Adams 2 161 Rebecca Adams 3 3477 sophie Adams 4 3478 Sophie Adams 1 3479 Tom Adams 4 3047 faron adamson 1 3480 John Adamson 1 3481 Jack Adcock 2 3482 Jon Adcock 3 3483