Paliganj Vitrani Krishak Samiti: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

Bikram, Patna

Bikram, Patna Bikram is a town and an assembly constituency in Paliganj subdivision of Patna district in the Indian state of Bihar. Bikram assembly constituency is part of Pataliputra (Lok Sabha constituency). Bikram assembly constituency covers Naubatpur and Bikram community development blocks, and Kaoria, Bindaul, Kunwa, Machchhalpur Lai, Yamunapur and Taranagar gram panchayats of Bihta Community Development Block. Bikram Choudhury, the creator of Bikram Yoga, personally trains and certifies his instructors to ensure that his methods and philosophy are preserved and properly taught. To be certified as an instructor in the Bikram Method of Yoga, an instructor must complete an intensive nine-week training session requiring over 500 hours of study. A studio guided by a certified Instructor provides the best possible instruction in the Bikram Method. Bikram, Patna. Quite the same Wikipedia. Just better. Bikram, Patna. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For disambiguation, see Bikram. City in Bihar, India. Bikram बिकà¥à¤°à¤®. City. Country. Bikram is a town and an assembly constituency in Paliganj subdivision of Patna district in the Indian state of Bihar.[1]. Bikram assembly constituency is part of Pataliputra (Lok Sabha constituency).[2] Bikram assembly constituency covers Naubatpur and Bikram community development blocks, and Kaoria, Bindaul, Kunwa, Machchhalpur Lai, Yamunapur and Taranagar gram panchayats of Bihta Community Development Block.[3]. Bikram, Patna, (Bihar). Bikram Bag, Sirmaur, (Himachal Pradesh). Bikram Bhisunpur, Kushinagar, (Uttar Pradesh). Bikramganj, Rohtas, (Bihar). Bikramnagar Bali, Hooghly, (West Bengal). Bikram is situated in Patna District , Bihar . Bikram Pincode is 801104 With 25.3271081 Latitude and 84.8007255 Longitude. -

Report of the Examiner of Local Accounts, Bihar For

REPORTOF THEEXAMINEROFLOCALACCOUNTS,BIHAR FORTHEYEARENDED 31STMARCH2009and2010 PANCHAYATRAJINSTITUTIONS GOVERNMENTOFBIHAR i TABLEOFCONTENTS Particulars Paragraph Page No. PrefaceVII OverviewIX CHAPTERͲI:IntroductiontoPRIsintheStateofBihar Background 1.1 1 StateProfile 1.2 1 OrganisationalStructureofPRIs 1.3 3 PowersandRolesofStateGovernmentinrelationto 1.4 4 PRIs DelegationofFunctionstoPRIs 1.5 5 BestPractices 1.6 6 AuditArrangement 1.7 6 AuditCoverage 1.8 7 StatusofRecoverybySurchargeProceedings 1.9 7 Impactofaudit 1.10 7 CHAPTERͲII:FinancialManagementandReporting FundFlowArrangement 2.1 8 NonͲrealisationofrevenue 2.2 9 Lossof` 1.34lakhduetoirregularremissionbythe 2.3 11 ChiefExecutiveOfficer Misappropriationof`0.23croreinPanchayatSamiti, 2.4 12 Punpun Advancesof`104.18crorelying 2.5 12 unadjusted/unrecovered Expenditureonidlestaff 2.6 12 MaintenanceofAccountsbyPRIs 2.7 13 Upkeepofrecords 2.8 14 StatusofpresentationofGPFSinPRI 2.9 15 Recommendation 2.10 16 CHAPTERͲIII:InternalControlMechanism Internalcontrols 3.1 17 i Commonlapsesinmaintenanceofrecordsrelatingto 3.2 17 executionofworks SegregationofDuties 3.3 18 Monitoring 3.4 18 InternalAudit 3.5 20 ExternalAudit 3.6 21 Poorresponsetoauditobservations 3.7 21 PersistenceofIrregularities 3.8 22 AnnualAdministrativeReport(AAR) 3.9 23 Recommendation 3.10 23 CHAPTERͲIV:ExecutionofSchemes SGRYschemes 4.1 24 IrregularitiesinSGRYschemesmeantforSC/ST 4.1.1 24 community IrregularitiesinExecutionofschemes 4.1.2 25 IrregularitiesrelatedtoFoodGrainsinSGRY 4.1.3 27 NationalRuralEmploymentGuaranteeAct/BREGS -

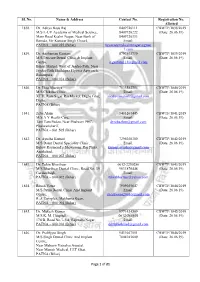

Cbwtf/1838/2019

Sl. No. Name & Address Contact No. Registration No. Allotted 1838. Dr. Aditya Basu Raj 8409726111 CBWTF/1838/2019 M/S L-UV Academy of Medical Science, 8409726222 (Date: 26.06.19) Main Road Keshri Nagar, Near Bank of 8409726333 Baroda, Vir Kunwar Singh Chowk, Email: PATNA – 800 025 (Bihar) luvacademykeshrinagar@gmai l.com 1839. Dr. Anshuman Gautam 8797503739 CBWTF/1839/2019 M/S Pericare Dental Clinic & Implant Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Centre, [email protected] Bihari Market, West of Jagdeo Path, Near Jagdeo Path Sheikhpra Flyover Approach, Rukanpura, PATNA – 800 014 (Bihar) 1840. Dr. Ekta Bhartiya 7033582754 CBWTF/1840/2019 M/S Chikitsa Clinic, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) XTTI, Ram Sagar Rai Market, Digha Ghat, [email protected] Digha, PATNA (Bihar) 1841. Zeba Alam 9431267445 CBWTF/1841/2019 M/S A Y Health Care, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Tam Tam Padao, Near Phulwari PHC, [email protected] Phulwarisharif, PATNA – 801 505 (Bihar) 1842. Dr. Ayusha Kumari 7295038300 CBWTF/1842/2019 M/S Daant Dental Speciality Clinic, Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Below Raymond’s Showroom, Raj Plaza, [email protected] Anishabad, PATNA – 800 002 (Bihar) 1843. Dr. Tuhin Bharthuar 0612-2250286 CBWTF/1843/2019 M/S Bharthuar Dental Clinic, Road No. 39, 9631876448 (Date: 26.06.19) Gardanibagh, Email: PATNA – 800 002 (Bihar) [email protected] 1844. Ritesh Vatsa 7909055647 CBWTF/1844/2019 M/S Patna Dental Clinic And Implant Email: (Date: 26.06.19) Centre, [email protected] R. J. Complex, Makhania Kuan, PATNA – 800 004 (Bihar) 1845. Dr. Mukesh Kumar 9771424509 CBWTF/1845/2019 M/S K. -

1997 Agrarian Conflict in Bihar.Pdf

\\re o$'e respect to the li.\,ing To the dead we orve nothing but the txth - \roltaire The organizcdkilling ofpoorpeasants _ and landl€ss labourers bymiddle and uppercaste landed amies and retaliation by N{arxist-Leninist organizations havc been na"lpoiots in tt e agrarian sccnc in Bihar ovcr the last filtccn years Hencc, this is not a ne\l phenomenon. What is relativclv ne\\, ho\\evd is thc entn,on the rural sccne in parts ofthe ccntral Bihar disrdcts ofBhojpur. Patna and Jchanabad oia nov uppcr castc land'ed organization callJUre Ralbir Scna It hes- ovcr the last thrcc vears. been rcsponsible lor a se"nes ofmassacrcs of poor. tural such thar rhe names ofobscurc viltagcs barhani tola. Haibo.p"., ffri-i"," \ bere these massacrcs - - had bcen pcrpetratcd became knorm to a *.ider public through the natlonal prcss In ordcr to gafu irst-hand information abour thesc incidents- about the actions and the rcsponscs olthc larious people's concemed, Union for Dcnocratic Rights (PUDR) sent a five-mcmbcr team ro thesc villagcs. It probed ninc incidcnts. ofvary ing kr"na. lti ing, t Ranbir Scna, ,encounters', i,t bt the ML parties, and real and fake. ttiia .o bv .p"."ukng to" rcsidents of these villages, membcrs of the Ranbir Scna, mcmbers of ,f4uoirt_i""i"nr.t organizations. the District Magistrates of Bhojpur, Jchanabad and patna and the Superintcndents ofPolice_ BhoJpur and patna. Following thc killing of the activrsr ofrhc CPI(ML) Liberation. Chandrashekhar, rn Si\\an^ district in late March. our team atso briefly visrtcd Si\ran rviih rhe lirnir.J locatlns the issu€s that dominate thc rural and urban sccne in St*.an dist.ict tlle team"il mct "f senlor part\ menb€rs. -

District Patna District Health Action Plan 2010-2011 National Rural Health

DISTRICT PATNA DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2010-2011 NATIONAL RURAL HEALTH MISSION GOVERNMENT OF BIHAR Developed & Designed by :- 1. Piyush Ranjan, DPM 2. Brahma Nand Roy, DAM 3. Shiv Krishna Murty, M & E Officer 1 Evaluation notes were added to the output document. To get rid of these notes, please order your copy of ePrint 5.0 now. Preface National Rural Health Mission was introduced to undertake architectural corrections in the public Health System of India. District health action plan is an integral aspect of National Rural Health Mission. District Health Action Plans are critical for achieving decentralisation, interdepartmental convergence, capacity building of health system and most importantly facilitating people’s participation in the health system’s programmes. District Health Action Planning provides opportunity and space to creatively design and utilise various NRHM initiatives such as flexi –financing, Rogi Kalyan Samiti, Village Health and Sanitation Committee to achieve our goals in the socio-cultural context of Patna. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) is a comprehensive health programme launched by Government of India to bring about architectural corrections in the health care delivery systems of India. The NRHM seeks to address existing gaps in the national public health system by introducing innovation, community orientation and decentralisation. The mission aims to provide quality health care services to all sections of society, especially for those residing in rural areas, women and children, by increasing the resources available for the public health system, optimising and synergising human resources, reducing regional imbalances in the health infrastructure, decentralisation and district level management of the health programmes and community participation as well as ownership of the health initiatives. -

Sch Code School Name Dist Name 11001 Zila School

BIHAR SCHOOL EXAMINATION BOARD PATNA DISTRICTWISE SCHOOL LIST 2013(CLASS X) SCH_CODE SCHOOL_NAME DIST_NAME 11001 ZILA SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11002 URSULINE CONVENT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11003 B B M HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11004 GOVT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11005 MAA KALI HIGH SCHOOL MADHUBANI PURNEA 11006 JLNS HIGH SCHOOL GULAB BAGH PURNEA 11007 PARWATI MANDAL HIGH SCHOOL HARDA PURNEA 11008 ANCHIT SAH HIGH SCHOOL BELOURI PURNEA 11009 HIGH SCHOOL CHANDI RAZIGANJ PURNEA 11010 GOVT HIGH SCHOOL SHRI NAGAR PURNEA 11011 SIYA MOHAN HIGH SCHOOL SAHARA PURNEA 11012 R P C HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA CITY PURNEA 11013 HIGH SCHOOL KASBA PURNEA 11014 K D GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KASBA PURNEA 11015 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL RANI PATRA PURNEA 11016 K G P H/S BHOGA BHATGAMA PURNEA 11017 N D RUNGTA H/S JALAL GARH PURNEA 11018 KALA NAND H/S GARH BANAILI PURNEA 11019 B N H/S JAGNICHAMPA NAGAR PURNEA 11020 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL GOKUL PUR PURNEA 11021 ST THOMAS H S MUNSHIBARI PURNEA PURNEA 11023 PURNEA H S RAMBAGH,PURNEA PURNEA 11024 HIGH SCHOOL HAFANIA PURNEA 11025 HIGH SCHOOL KANHARIA PURNEA 11026 KANAK LAL H/S SOURA PURNEA 11027 ABUL KALAM HIGH SCHOOL ICHALO PURNEA 11028 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL AMOUR PURNEA 11029 HIGH SCHOOL RAUTA PURNEA 11030 HIGH SCHOOL AMOUR PURNEA 11031 HIGH SCHOOL BAISI PURNEA 11032 HIGH SCHOOL JHOWARI PURNEA 11033 JANTA HIGH SCHOOL BISHNUPUR PURNEA 11034 T N HIGH SCHOOL PIYAZI PURNEA 11035 HIGH SCHOOL KANJIA PURNEA 11036 PROJECT KANYA H S BAISI PURNEA 11037 UGRA NARAYAN H/S VIDYAPURI PURNEA 11038 BALDEVA H/S BHAWANIPUR RAJDHAM -

World Bank Document

MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS (Government of India) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT (Main Report) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Project Report for Rehabilitation and Up-gradation to 2-Lane/2-Lane with Paved Shoulders and Strengthening of Fathua-Harnaut-Barh Section (km 0 to km 69) of NH 30 A in the State of Bihar. (Package No. SP/A/7) February 2014 C O N S U L T I N G Engineers Group Ltd. Public Disclosure Authorized An ISO 9001 : 2000 Company CEG Tower, B-11 (G), Malviya Industrial Area, JAIPUR – 302 017 (INDIA) Phone: +91 (141) 275 1801 – 806 (6 lines); Fax: +91 (141) 252 1348 Email: [email protected] Rehabilitation and upgrading to 2 lane/2 lane with paved shoulder of EIA/EMP Report NH-30A in the State of Bihar TABLE OF CONTENTS S. No. Description Page No FORM -1 ABBREVIATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES-1 Introduction E1 ES-2 Project Description E2 ES-2.1 Existing and Proposed the Project Road E3 ES-3 Regulatory Framework and Institutional Regime E4 ES-4 Description of Existing Environment E5 ES-4.1.1 Meteorology E8 ES-4.1.2 Ambient Air Quality E8 ES-4.2 Ambient Noise Level E9 ES-5 Analysis of Alignment Alternatives E10 ES-6 Impact Assessment and Mitigation Measures E10 ES-7 Environmental Monitoring Programme E14 ES-8 Additional Studies E15 ES-9 Environmental Management Plan E16 ES-10 Conclusion E17 ES-11 Disclosures of Consultant Engaged E17 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Project 1 1.2 Project Proponent 3 1.3 Objective and Need of Environmental Impact Assessment 4 Consulting Engineers Group Ltd i MoRTH Rehabilitation and upgrading to 2 lane/2 lane with paved shoulder of EIA/EMP Report NH-30A in the State of Bihar S. -

Evaluation of Hydrogeology of the Lower Son Valley Based on Remote Sensing Data

Journal of Geographic Information System, 2010, 2, 220-227 doi:10.4236/jgis.2010.24031 Published Online October 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jgis) Evaluation of Hydrogeology of the Lower Son Valley Based on Remote Sensing Data Manas Banerjee1*, Debolin Bhattacharya1, Hriday Narain Singh1, Daya Shanker2 1Department of Geophysics, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India 2Department of Earthquake Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee, India E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received July 31, 2010; revised September 2, 2010; accepted September 8, 2010 Abstract Remote sensing, one of the most important reconnaissance and feature identifying tools generally applied for surface and groundwater investigation, was used for water resources mapping for the lower Son Valley in this study. The mapping was done with the help of Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellite imagery IRS-LISS- 1-B1 for January 29, 1991 obtained during the day transit time. The area under study comprises adjoining parts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states of India and extends over the seven districts, namely Bhojpur, Rohtas, Patna, Jahanabad, Aurangabad, Ballia and Chapra. Geology of the study area is quite complex, tectonically disturbed and shows four major cycles of depositions after erosions during last one billion years (since Cre- taceous). Two lineaments mapped by GSI (Geological Survey of India) in western side of river Son in the Bhojpur district can also be identified by the satellite imagery. In the present study, apart from these linea- ments, two new lineaments have been investigated, which run almost parallel to river Ganga in northwest parts of the area in Ballia district. -

Case Studies Chapter-Iii

SECTION - II CASE STUDIES CHAPTER-III BIHAR EXPERIMENT 3.1 Introduction 3.1.1 In Bihar the experiment with farmers participation in canal irrigation management has been of recent origin. Till October 1998 farmers' associations were formed in 37 channels and distributaries in the State. Farmers of 13 more distributaries had since agreed to take over management of their channels anxc d applied for registration. Of the 37 Associations already formed, Paliganj Distributary on Sone Canal System is the oldest. Here management transfer has already taken place. It was, therefore, selected for the study. 3.1.2 Immediately after getting some experience on PIM in Paliganj, the state government introduced similar experiments in other distributaries as stated above. This too was in collaboration with WALMI. One such medium irrigation project namely Asarganj distributory of Badua canal in Bhagalpur district was also taken up for detailed study in consultation with state level authorities and WALMI's experts. 3.1.3 Bihar had a large number of tubewells most of which did not function for one reason or the other. Attempts made in the pest to transfer them to Panchayati did not succeed. Hardly 50 percent of the tubewells were taken over by Panchayats. Meanwhile under the requirement of the World Bank Bihar Plateau Development Projects WUAs were under formation within the area covered by this Project. Another significant development, was the passing of a resolution by the state government on 14th May 1998 whereby it was decided to transfer state tubewells to WUAs to be formed under the State Cooperative Act 1996. -

BIHAR STATE POWER TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED (Reg

BIHAR STATE POWER TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED (Reg. Office: 4th Floor, Vidyut Bhawan, Bailey Road, Patna-800021) (CIN- U40102BR2012SGC018889) (Department of Power Management Cell) BSPTCL has revised the Business Plan, the copy of the same is attached herewith for ready reference also the revised para-wise in respect of earlier reply vide letter no.- 379 dated – 20/12/2018 regarding Business Plan (BP) for FY 2019-20 to FY 2021-22 submitted to Hon’ble BERC vide Letter No.- 330 dated – 02.11.2018 1. (a) The mentioned are indicated as below with units: S. No. of 3.5.1 of BP Units of Amount 11 to 13 In Crore 29 to 31 In Crore 32 In Rupees 39 In Crore 53 to 60 In Rupees 70 to 74 In Crore 75 to 77 In Rupees 78 to 80 In Crore (b) At Sl. No.- 7 & 22 of 3.6 of Business plan claimed twice which may treated as same and Sl. No.- 22 may be deleted. (c) Also at Sl. No.- 65 & 66 of 3.5.1 of Business plan : It is not a type of repetition, these are of two different transmission lines: S.No. Name of Element (Transmission line, Commissioning COST(Rs.) Scheme Substation, Bay Extension, etc.) Date/LDOC) Procurement and Construction of 33KV line bays in form of Indoor VCB panels at 14 65 30.11.2018 33.02 Crore ADB nos. of AIS Sub-station under Transmission Circle Gaya Procurement and Construction of 33KV line bays in form of Indoor VCB panels at 14 66 30.11.2018 40.25 Crore ADB nos. -

Valuation of Irrigation Water for Two Principal Crops in Paliganj Distributary of Bihar, India

Water Utility Journal 25: 31-39, 2020. © 2020 E.W. Publications Valuation of irrigation water for two principal crops in Paliganj distributary of Bihar, India A. Upadhyaya1* and L.B. Roy2 1 Division of Land and Water Management, ICAR Research Complex for Eastern Region, Patna – 800014, India 2 Department of Civil Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Patna – 800005, India * e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: A lot of investment has been done in creating irrigation potential in India. On account of this, it increased more than five times since 1951. But recovery from the created irrigation potential is very low, leading to poor performance of irrigation sector. Highly subsidised irrigation water price, which does not reflect true irrigation water supply cost, is the main cause of slow revenue recovery. Low irrigation water pricing results in indiscriminate and unscrupulous use of irrigation water in upper, middle and tail reaches of a canal, leading to either waterlogging or water deficit situations. Since more than two decades, irrigation water charges have not been revised in many states and as a result revenue from water is not increasing. In the future, agriculture is going to face a new challenge of producing more from less water available, because more water is being diverted towards industries, urban and domestic sectors. Under such an alarming situation, it was thought to assess the price of irrigation water for producing a kilogram of rice and wheat in the command of Paliganj distributary located in Bihar under Sone canal system in India. Data about price of tube well water and canal water to be paid by farmers as decided by State Water Resources Department were collected and data about agricultural inputs applied and outputs produced by the farmers were collected through a developed questionnaire.