Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 09:25:52PM Via Free Access 1 of 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London 2012- Schedule by Sport

LONDON- 2012 Schedule by sport Opening Ceremony Closing Ceremony Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Dates: Friday 27 July Dates: Sunday 12 August Archery Gymnastics – Trampoline Venue: Lord’s Cricket Ground Venue: North Greenwich Arena Dates: Friday 27 July – Friday 3 August Dates: Friday 3 – Saturday 4 August Athletics Handball Venue: Olympic Park – Olympic Stadium Venue: Olympic Park – Handball Arena; Olympic Park – Dates: Friday 3 – Saturday 11 August Basketball Arena Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Athletics – Marathon Hockey Venue: London Venue: Olympic Park – Hockey Centre Date: Sunday 5 and Sunday 12 August Dates: Sunday 29 July – Saturday 11 August Athletics - Race Walk Judo Venue: London Venue: ExCel Dates: Saturday 4 and Saturday 11 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Friday 3 August Badminton Modern Pentathlon Venue: Wembley Arena Venue: Olympic Park and Greenwich Park Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 5 August Dates: Saturday 11 – Sunday 12 August Basketball Rowing Venue: Olympic Park – Basketball Arena and North Venue: Eton Dorney Greenwich Arena Dates: Saturday 28 July – Saturday 4 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Beach Volleyball Sailing Venue: Horse Guards Parade Venue: Weymouth and Portland Dates: Saturday 28 July – Thursday 9 August Dates: Sunday 29 July – Saturday 11 August Boxing Shooting Venue: ExCeL Venue: The Royal Artillery Barracks Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 12 August Dates: Saturday 28 July – Sunday 5 August Canoe Slalom Swimming Venue: Lee -

Smash Hits Volume 52

-WjS\ 35p USA $175 27 November -10 December I98i -HITLYRtCS r OfPER TROUPER TMCOMINgOUT EMBARRASSMENT MOTORHEAD NOT THE 9 O'CLOCK NEWS FRAMED BLONDIE PRINTS to be won 3 (SHU* Nov 27 — Dec 10 1980 Vol.2 No.24 ^gTEW^lSl TO CUT A LONG STORY SHORT Spandau Ballet 3 ELSTREE Buggies .....10 EMBARRASSMENT Madness 10 SUPER TROUPER Abba 11 I'M COMING OUT Diana Ross 17 BOURGIEBOURGIE Gladys Knight & The Pips 17 I LIKE WHAT YOU'RE DOING TO ME Young & Co ...23 WOMEN IN UNIFORM Iron Maiden 26 I COULD BE SO GOOD FOR YOU Dennis Waterman 26 SPENDING THE NIGHT TOGETHER Dr. Hook 32 LONELY TOGETHER Barry Manilow 32 TREASON The Teardrop Explodes 35 DO YOU FEEL MY LOVE Eddy Grant 38 THE CALL UP The Clash 38 LOOKING FOR CLUES Robert Palmer 47 TOYAH: Feature 4/5/6 NOT THE 9 O'CLOCK NEWS: Feature 18/19 UB40: Colour Poster 24/25 MOTORHEAD: Feature 36/37 MADNESS: Colour Poster 48 CARTOON 9 HIGHHORDSE 9 BITZ 12/13/14 INDEPENDENT BITZ 21 DISCO 22 CROSSWORD 27 REVIEWS 28/29 STAR TEASER 30 FACT IS 31 BIRO BUDDIES 40 BLONDIE COMPETITION 41 LETTERS 43/44 BADGE & CALENDAR OFFERS 44 GIGZ 46 Editor Editorial Assistants Contributors Ian Cranna Bev Hillier Robin Katz Linda Duff Red Starr Fred DeMar Features Editor David Hepworth Advertisement Manager Mike Stand Rod Sopp JiH Furmanovsky (Tel: 01-4398801) Mark Casto Design Editor Steve Taylor Assistant Steve Bush Mark Ellen Adte Hegarty Production Editor Editorial Consultant Publisher Kasper de Graaf Nick Logan Peter Strong Editorial and Advertising address: Smash Hits. -

London 2012 Venues Guide

Olympic Delivery Authority London 2012 venues factfi le July 2012 Venuesguide Contents Introduction 05 Permanent non-competition Horse Guards Parade 58 Setting new standards 84 facilities 32 Hyde Park 59 Accessibility 86 Olympic Park venues 06 Art in the Park 34 Lord’s Cricket Ground 60 Diversity 87 Olympic Park 08 Connections 36 The Mall 61 Businesses 88 Olympic Park by numbers 10 Energy Centre 38 North Greenwich Arena 62 Funding 90 Olympic Park map 12 Legacy 92 International Broadcast The Royal Artillery Aquatics Centre 14 Centre/Main Press Centre Barracks 63 Sustainability 94 (IBC/MPC) Complex 40 Basketball Arena 16 Wembley Arena 64 Workforce 96 BMX Track 18 Olympic and Wembley Stadium 65 Venue contractors 98 Copper Box 20 Paralympic Village 42 Wimbledon 66 Eton Manor 22 Parklands 44 Media contacts 103 Olympic Stadium 24 Primary Substation 46 Out of London venues 68 Riverbank Arena 26 Pumping Station 47 Map of out of Velodrome 28 Transport 48 London venues 70 Water Polo Arena 30 Box Hill 72 London venues 50 Brands Hatch 73 Map of London venues 52 Eton Dorney 74 Earls Court 54 Regional Football stadia 76 ExCeL 55 Hadleigh Farm 78 Greenwich Park 56 Lee Valley White Hampton Court Palace 57 Water Centre 80 Weymouth and Portland 82 2 3 Introduction Everyone seems to have their Londoners or fi rst-time favourite bit of London – visitors – to the Olympic whether that is a place they Park, the centrepiece of a know well or a centuries-old transformed corner of our building they have only ever capital. Built on sporting seen on television. -

Standard Resolution 19MB

The e-journal of analog and digital sound. no.24 2009 NOTHING BUT ANALOG! MoMA’s New York Clearaudio, Lyra, Air Tight and More NEW Punk Exhibit Grateful Dead Book By Ben Fong-Torres STYLE: We Ride Ducati’s Newest Supermotard At Indy! Box Sets: AC/DC and Thelonius Monk Perreaux Returns to the US Bob Gendron Goes To NYC to View Punk’s Past at MoMA TONE A 1 NO.24 2 0 0 9 PUBLISHER Jeff Dorgay EDITOR Bob Golfen ART DIRECTOR Jean Dorgay r MUSIC EDITOR Ben Fong-Torres ASSISTANT Bob Gendron MUSIC EDITOR M USIC VISIONARY Terry Currier STYLE EDITOR Scott Tetzlaff C O N T R I B U T I N G Tom Caselli WRITERS Kurt Doslu Anne Farnsworth Joe Golfen Jesse Hamlin Rich Kent Ken Kessler Hood McTiernan Rick Moore Jerold O’Brien Michele Rundgren Todd Sageser Richard Simmons Jaan Uhelszki Randy Wells UBER CARTOONIST Liza Donnelly ADVERTISING Jeff Dorgay WEBSITE bloodymonster.com Cover Photo: Blondie, CBGB’s. 1977. Photograph by Godlis, Courtesy Museum of Modern Art Library tonepublications.com Editor Questions and Comments: [email protected] 800.432.4569 © 2009 Tone MAGAZIne, LLC All rights reserved. TONE A 2 NO.24 2 0 0 9 55 (on the cover) MoMA’s Punk Exhibit features Old School: 1 0 The Audio Research SP-9 By Kurt Doslu Journeyman Audiophile: 1 4 Moving Up The Cartridge Food Chain By Jeff Dorgay The Grateful Dead: 29 The Sound & The Songs By Ben Fong-Torres A BLE Home Is Where The TURNta 49 FOR Record Player Is EVERYONE By Jeff Dorgay Here Today, Gone Tomorrow: 55 MoMA’s New York Punk Exhibit By Bob Gendron Budget Gear: 89 How Much Analog Magic Can You Get for Under $100? By Jerold O’Brien by Ben Fong-Torres, published by Chronicle Books 7. -

Gary Numan - Hammersmith Apollo, London - November 28, 2014

1 Gary Numan - Hammersmith Apollo, London - November 28, 2014 by Mireille Beaulieu Original French version © Obsküre magazine - http://www.obskuremag.net http://www.obskuremag.net/articles/gary-numan-live-hammersmith-apollo-londres- 28112014/ Gary Numan’s recent concert at London’s Hammersmith Apollo had long been announced as a major event. This show was the crowning moment of the world tour Numan had undertaken in October 2013, as he was promoting his new album Splinter (Songs from a broken mind ). Undoubtedly one of the artist’s major works, Splinter garnered unparalleled public and critical acclaim. It even entered the UK Top 20 – the first Numan album to do so since Warriors in 1983. Gary Numan started this long tour in the US before visiting the UK, Ireland, Israel, continental Europe (but sadly not Paris), Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Photos: Louise Barnes and Jim Napier © Jim Napier 2 But it was also a “homecoming concert”, a return to his roots for Numan, who currently resides in Los Angeles. For the first time since 1996, he was to take over the Hammersmith Apollo, the legendary UK venue formerly known as the Hammersmith Odeon. This is where David Bowie killed off his Ziggy Stardust character in 1973... Around the same period, a teenage Gary (then still Gary Webb) would often attend gigs there. Then, with the explosion of the Numan phenomenon in 1979, the “Hammy” became for many years the London venue of his choice when he was touring. Gary, who was born in Hammersmith, obviously has a deep connection with the place. -

Spire July & August 2010.Pdf

The American Church in Paris Tel.: 01.40.62.05.00 Fax: 01.40.62.05.11 www.acparis.org 65, quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris, France July/August 2010 From Rev. Scott Herr we also should take the coming months as Senior Pastor an opportunity to spend more time reflecting on God’s presence in all of creation, even in the city? Remember at Rest is good for all of Dear Members and Friends of the ACP, us, all of creation. Summer is a wonderful time to rediscover Some might say that the gift of Sabbath rest and refreshment. Summer is a time when nature reminds us resting might have that so much life and beauty happens helped avoid despite all of our worry and toil. The countless heart sunshine, grass, trees and flowers are all so beautiful, no thanks to us! We can attacks, divorces, simply behold, admire and absorb the wars, oil spills. beauty of God’s creation. Artists seem to understand Jesus’ invitation to “Consider the lilies…” Impressionist painter Claude Monet spent much time savoring the the root of the word contemplate is the reflections of color at his garden in word “temple.” We don’t have to have to Giverny. One of his practices was “visual be in a literal temple to realize God’s meditation.”1 presence and peace. We can stop and see again (re-spect?) the glory of the Lord wherever we are, even in the faces of a Remember, at the root crowd of tourists walking along the quai… Paradoxically, rest and refreshment of the word require intentionality. -

2007 Europe Spring Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 2007 EUROPE SPRING TOUR MARCH 27 Stockholm, Sweden Debaser Medis 28 Washington, D.C. Theme Time Radio Hour, Episode 47: Fools 28 Stockholm, Sweden Globe Arena 30 Oslo, Norway Spektrum APRIL Gothenburg, Sweden Scandinavium 1 2 Copenhagen, Denmark Forum Washington, D.C. Theme Time Radio Hour, Episode 48: New York 4 Hamburg, Germany Colorline Arena 5 Münster, Germany Halle Münsterland 6 Brussels, Belgium Vorst Nationaal 8 Amsterdam, The Netherlands Heineken Music Hall 9 Amsterdam, The Netherlands Heineken Music Hall 11 Washington, D.C. Theme Time Radio Hour, Episode 49: Death & Taxes 11 Glasgow, Scotland Scottish Exhibition And Conference Center 12 Newcastle, England Metro Radio Arena 14 Sheffield, England Hallam FM Arena 15 London, England Wembley Arena 16 London, England Wembley Arena 17 Birmingham, England National Indoor Arena (NIA) 18 Washington, D.C. Theme Time Radio Hour, Episode 50: Spring Cleaning 19 Düsseldorf, Germany Philipshalle 20 Stuttgart, Germany Porsche Arena 21 Frankfurt, Germany Jahrhunderthalle 23 Paris, France Palais Omnisports de Paris 25 Geneva, Switzerland Geneva Arena 26 Turin, Italy Palaolimpico Isozaki 27 Milan, Italy Forum di Assago 29 Zürich, Switzerland Hallenstadion 30 Mannheim, Germany SAP Arena MAY 2 Leipzig, Germany Leipzig Arena 3 Berlin, Germany Max Schmeling Halle 5 Herning, Denmark Herninghalle Bob Dylan: Still On The Road – 2007 Europe Spring Tour Bob Dylan: Still On The Road – 2007 Europe Spring Tour 28958 Debaser Medis Stockholm, Sweden 27 March 2007 1. Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I'll Go Mine) 2. Not Dark Yet 3. I'll Be Your Baby Tonight 4. It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) 5. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Consolidated Financial Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2006

6-7-35 Kitashinagawa Shinagawa-ku News & Information Tokyo 141-0001 Japan No: 06-035E 3:00 P.M. JST, April 27, 2006 Consolidated Financial Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2006 Tokyo, April 27, 2006 -- Sony Corporation today announced its consolidated results for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2006 (April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2006). (Billions of yen, millions of U.S. dollars, except per share amounts) Fiscal Year ended March 31 Change in 2005 2006 Yen 2006* Sales and operating revenue ¥7,159.6 ¥7,475.4 +4.4% $63,893 Operating income 113.9 191.3 +67.9 1,635 Income before income taxes 157.2 286.3 +82.1 2,447 Equity in net income of affiliated 29.0 13.2 -54.6 113 companies Net income 163.8 123.6 -24.5 1,057 Net income per share of common stock — Basic ¥175.90 122.58 -30.3% $1.05 — Diluted 158.07 116.88 -26.1 1.00 * U.S. dollar amounts have been translated from yen, for convenience only, at the rate of ¥117=U.S.$1, the approximate Tokyo foreign exchange market rate as of March 31, 2006. Unless otherwise specified, all amounts are on the basis of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in the U.S. (“U.S. GAAP”). Consolidated Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2006 Sales and operating revenue (“sales”) increased 4.4% compared with the previous fiscal year; on a local currency basis sales increased slightly. (For all references herein to results on a local currency basis, see Note I on page 9.) Sales within the Electronics segment increased 1.7% (a 3% decrease on a local currency basis). -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Audience Hears Recorded Music at Il Divo Concert | Artsatl 8/21/12 1:10 PM

Silenced: ASO used as musical “prop,” audience hears recorded music at Il Divo concert | ArtsATL 8/21/12 1:10 PM SEARCH ? ? ? ? FOLLOW US ABOUT US/CONTACT SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER SHARING THIS ARTICLE Silenced: ASO used as musical “prop,” audience hears recorded music at Il Divo concert AUTHOR August 14, 2012 Mark Gresham TEXT SIZE MORE ARTICLES BY AUTHOR By MARK GRESHAM Will ASO musicians be “locked out”? As deadline looms, union offers to take 11 percent pay cut Atlanta Chamber Players announce semi-finalists in national Rapido! contest The ArtsATL Q&A (Part 2): Joe Bankoff on creativity, community, Midtown and Atlanta’s future Il Divo's management preferred prerecorded music to live ASO musicians. Sunday night’s concert at the Verizon Wireless Amphitheatre was billed as “Il Divo and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra,” but what the audience heard over the sound system was not the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Instead, it heard prerecorded audio tracks by an entirely different orchestra. The Il Divo singers were live, but the orchestra was relegated to the role of visual window dressing. According to sources, the musicians were informed at the beginning of a three-hour rehearsal in the afternoon that another orchestra’s audio tracks would be heard by the audience. The tracks included instruments that were not present on stage, such as a synthesized bass guitar. Melissa Sanders, the ASO’s senior director of communications, confirmed late Monday that the ASO management on site at Verizon also didn’t find out until the rehearsal that while the orchestra would perform the music live, the audience would hear the prerecorded http://www.artsatl.com/2012/08/atlanta-symphony-forced-pantomime-pre-recorded-tracks-sunday’s-il-divo-concert/ Page 1 of 12 Silenced: ASO used as musical “prop,” audience hears recorded music at Il Divo concert | ArtsATL 8/21/12 1:10 PM orchestra. -

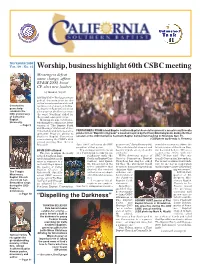

Worship, Business Highlight 60Th CSBC Meeting Messengers Defeat Name Change, Affirm BF&M 2000, Boost CP, Elect New Leaders by Mark A

DECEMBER 2000 VOL. 59 • NO. 15 Worship, business highlight 60th CSBC meeting Messengers defeat name change, affirm BF&M 2000, boost CP, elect new leaders by Mark A. Wyatt RIVERSIDE — The largest evan- gelical denomination in the nation’s most populous state will Convention- continue to be known as Califor- goers help nia Southern Baptist Convention celebrate the after a vote on whether to remove 50th anniversary the word “Southern” failed for of California the second consecutive year. Baptist Messengers also voted over- University. whelmingly to affirm the latest — Page 9 version of “The Baptist Faith and Message” statement of doc- trinal beliefs and to increase Co- PERFORMERS FROM Inland Empire Southern Baptist Association present a massive multi-media operative Program giving to production of “Experiencing God,” a musical inspired by the Henry Blackaby book, during the final Southern Baptist Convention session of the 2000 California Southern Baptist Convention meeting in Riverside Nov. 15. causes during the CSBC’s 60th (CSB photo by Brenda S. Flowers) annual meeting, Nov. 14-15 in Riverside. June 2000” and notify the SBC go on record,” Spradlin insisted. vored the motion to affirm the president of that action. “It is a doctrinal statement and latest version of Southern Bap- BF&M 2000 affirmed “It’s an important time for us doesn’t impede on any church’s tist doctrinal beliefs. “We are a The vote to affirm the newly as a Convention to express our authority.” cooperating entity with the revised Southern Bap- solidarity with the Willie Simmons, pastor of SBC,” Nelson said. “Our (na- tist doctrinal statement Southern Baptist Con- Greater Cornerstone Baptist tional) Convention has spoken.