Endpoints of Stellar Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasma Physics and Pulsars

Plasma Physics and Pulsars On the evolution of compact o bjects and plasma physics in weak and strong gravitational and electromagnetic fields by Anouk Ehreiser supervised by Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia as part of an internship at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy, Bonn March 2010 2 This composition was written as part of two internships at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in April 2009 at the Radiotelescope in Effelsberg and in February/March 2010 at the Institute in Bonn. I am very grateful for the support, expertise and patience of Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia, who supervised my internship and introduced me to the basic concepts and the current research in the field. Contents I. Life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure 2. Gravitational collapse and supernova 3. Star remnants II. Properties of Compact Objects 1. White Dwarfs 2. Neutron Stars 3. Black Holes 4. Hypothetical Quark Stars 5. Relativistic Effects III. Plasma Physics 1. Essentials 2. Single Particle Motion in a magnetic field 3. Interaction of plasma flows with magnetic fields – the aurora as an example IV. Pulsars 1. The Discovery of Pulsars 2. Basic Features of Pulsar Signals 3. Theoretical models for the Pulsar Magnetosphere and Emission Mechanism 4. Towards a Dynamical Model of Pulsar Electrodynamics References 3 Plasma Physics and Pulsars I. The life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure Stars are formed in molecular clouds in the interstellar medium, which consist mostly of molecular hydrogen (primordial elements made a few minutes after the beginning of the universe) and dust. -

Beyond the Solar System Homework for Geology 8

DATE DUE: Name: Ms. Terry J. Boroughs Geology 8 Section: Beyond the Solar System Instructions: Read each question carefully before selecting the BEST answer. Use GEOLOGIC VOCABULARY where APPLICABLE! Provide concise, but detailed answers to essay and fill-in questions. Use an 882-e scantron for your multiple choice and true/false answers. Multiple Choice 1. Which one of the objects listed below has the largest size? A. Galactic clusters. B. Galaxies. C. Stars. D. Nebula. E. Planets. 2. Which one of the objects listed below has the smallest size? A. Galactic clusters. B. Galaxies. C. Stars. D. Nebula. E. Planets. 3. The Sun belongs to this class of stars. A. Black hole C. Black dwarf D. Main-sequence star B. Red giant E. White dwarf 4. The distance to nearby stars can be determined from: A. Fluorescence. D. Stellar parallax. B. Stellar mass. E. Emission nebulae. C. Stellar distances cannot be measured directly 5. Hubble's law states that galaxies are receding from us at a speed that is proportional to their: A. Distance. B. Orientation. C. Galactic position. D. Volume. E. Mass. 6. Our galaxy is called the A. Milky Way galaxy. D. Panorama galaxy. B. Orion galaxy. E. Pleiades galaxy. C. Great Galaxy in Andromeda. 7. The discovery that the universe appears to be expanding led to a widely accepted theory called A. The Big Bang Theory. C. Hubble's Law. D. Solar Nebular Theory B. The Doppler Effect. E. The Seyfert Theory. 8. One of the most common units used to express stellar distances is the A. -

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

A Star Is Born

A STAR IS BORN Overview: Students will research the four stages of the life cycle of a star then further research the ramifications of the stage of the sun on Earth. Objectives: The student will: • research, summarize and illustrate the proper sequence in the life cycle of a star; • share findings with peers; and • investigate Earth’s personal star, the sun, and what will eventually come of it. Targeted Alaska Grade Level Expectations: Science [9] SA1.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the processes of science by asking questions, predicting, observing, describing, measuring, classifying, making generalizations, inferring, and communicating. [9] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by recognizing that a star changes over time. [10-11] SA1.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the processes of science by asking questions, predicting, observing, describing, measuring, classifying, making generalizations, analyzing data, developing models, inferring, and communicating. [10] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by recognizing phenomena in the universe (i.e., black holes, nebula). [11] SD4.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the theories regarding the origin and evolution of the universe by describing phenomena in the universe (i.e., black holes, nebula). Vocabulary: black dwarf – the celestial object that remains after a white dwarf has used up all of its -

The Endpoints of Stellar Evolution Answer Depends on the Star’S Mass Star Exhausts Its Nuclear Fuel - Can No Longer Provide Pressure to Support Itself

The endpoints of stellar evolution Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Low mass stars (< 8 Msun or so): End up with ‘white dwarf’ supported by degeneracy pressure. Wide range of structure and composition!!! Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Higher mass stars (8-25 Msun or so): get a ‘neutron star’ supported by neutron degeneracy pressure. Wide variety of observed properties Answer depends on the star’s mass Star exhausts its nuclear fuel - can no longer provide pressure to support itself. Gravity takes over, it collapses Above about 25 Msun: we are left with a ‘black hole’ Black holes are astounding objects because of their simplicity (consider all the complicated physics to set all the macroscopic properties of a star that we have been through) - not unlike macroscopic elementary particles!! According to general relativity, the black hole properties are set by two numbers: mass and spin change of photon energies towards the gravitating mass the opposite when emitted Pound-Rebka experiment used atomic transition of Fe Important physical content for BH studies: general relativity has no intrisic scale instead, all important lengthscales and timescales are set by - and become proportional to the mass. Trick… Examine the energy… Why do we believe that black holes are inevitably created by gravitational collapse? Rather astounding that we go from such complicated initial conditions to such “clean”, simple objects! . -

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) my views are evolving on the subject Today’s Topics Stellar Evolution • An alien visits Earth for a day • A star’s mass controls its fate • Low-mass stellar evolution (M < 2 M) • Intermediate and high-mass stellar evolution (2 M < M < 8 M; M > 8 M) • Novae, Type I Supernovae, Type II Supernovae An Alien Visits for a Day • Suppose an alien visited the Earth for a day • What would it make of humans? • It might think that there were 4 separate species • A small creature that makes a lot of noise and leaks liquids • A somewhat larger, very energetic creature • A large, slow-witted creature • A smaller, wrinkled creature • Or, it might decide that there is one species and that these different creatures form an evolutionary sequence (baby, child, adult, old person) Stellar Evolution • Astronomers study stars in much the same way • Stars come in many varieties, and change over times much longer than a human lifetime (with some spectacular exceptions!) • How do we know they evolve? • We study stellar properties, and use our knowledge of physics to construct models and draw conclusions about stars that lead to an evolutionary sequence • As with stellar structure, the mass of a star determines its evolution and eventual fate A Star’s Mass Determines its Fate • How does mass control a star’s evolution and fate? • A main sequence star with higher mass has • Higher central pressure • Higher fusion rate • Higher luminosity • Shorter main sequence lifetime • Larger -

SHAPING the WIND of DYING STARS Noam Soker

Pleasantness Review* Department of Physics, Technion, Israel The role of jets in the common envelope evolution (CEE) and in the grazing envelope evolution (GEE) Cambridge 2016 Noam Soker •Dictionary translation of my name from Hebrew to English (real!): Noam = Pleasantness Soker = Review A short summary JETS See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A very short summary JFM See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • Jets: Can be launched outside and Secondary inside the envelope star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets Jets Jets: And on its surface Secondary star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • When the jets mange to eject the envelope outside the orbit of the secondary star, the system avoids a common envelope evolution (CEE). This is the Grazing Envelope Evolution (GEE). Points to consider (P1) The JFM (jet feedback mechanism) is a negative feedback cycle. But there is a positive ingredient ! In the common envelope evolution (CEE) more mass is removed from zones outside the orbit. -

Features in Cosmic-Ray Lepton Data Unveil the Properties of Nearby Cosmic Accelerators

Prepared for submission to JCAP Features in cosmic-ray lepton data unveil the properties of nearby cosmic accelerators O. Fornieri,a;b;d;1 D. Gaggerod and D. Grassob;c aDipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, della Terra e dell'Ambiente, Universit`adi Siena, Via Roma 56, 53100 Siena, Italy bINFN Sezione di Pisa, Polo Fibonacci, Largo B. Pontecorvo 3, 56127 Pisa, Italy cDipartimento di Fisica, Universit`adi Pisa, Polo Fibonacci, Largo B. Pontecorvo 3 dInstituto de F´ısicaTe´oricaUAM-CSIC, Campus de Cantoblanco, E-28049 Madrid, Spain E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. We present a comprehensive discussion about the origin of the features in the leptonic component of the cosmic-ray spectrum. Working in the framework of a up-to-date CR transport scenario tuned on the most recent AMS-02 and Voyager data, we show that the prominent features recently found in the positron and in the all-electron spectra by several experiments are compatible with a scenario in which pulsar wind nebulae (PWNe) are the dominant sources of the positron flux, and nearby supernova remnants (SNRs) shape the high-energy peak of the electron spectrum. In particular we argue that the drop-off in positron spectrum found by AMS-02 at 300 GeV can be explained | under different ∼ assumptions | in terms of a prominent PWN that provides the bulk of the observed positrons in the 100 GeV domain, on top of the contribution from a large number of older objects. ∼ Finally, we turn our attention to the spectral softening at 1 TeV in the all-lepton spectrum, ∼ recently reported by several experiments, showing that it requires the presence of a nearby arXiv:1907.03696v2 [astro-ph.HE] 6 Mar 2020 supernova remnant at its final stage. -

Equation of State of a Dense and Magnetized Fermion System Israel Portillo Vazquez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2011-01-01 Equation Of State Of A Dense And Magnetized Fermion System Israel Portillo Vazquez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Portillo Vazquez, Israel, "Equation Of State Of A Dense And Magnetized Fermion System" (2011). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2365. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2365 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EQUATION OF STATE OF A DENSE AND MAGNETIZED FERMION SYSTEM ISRAEL PORTILLO VAZQUEZ Department of Physics APPROVED: Efrain J. Ferrer , Ph.D., Chair Vivian Incera, Ph.D. Mohamed A. Khamsi, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Acting Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Israel Portillo Vazquez 2011 EQUATION OF STATE OF A DENSE AND MAGNETIZED FERMION SYSTEM by ISRAEL PORTILLO VAZQUEZ, MS THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physics THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO August 2011 Acknowledgements First, I would like to acknowledge the advice and guidance of my mentor Dr. Efrain Ferrer. During the time I have been working with him, the way in which I think about nature has changed considerably. -

Supernova Environmental Impacts

Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union IAU Symposium No. 296 IAU Symposium IAU Symposium 7–11 January 2013 New telescopes spanning the full electromagnetic spectrum have enabled the study of supernovae (SNe) and supernova remnants 296 Raichak on Ganges, (SNRs) to advance at a breath-taking pace. Automated synoptic Calcutta, India surveys have increased the detection rate of supernovae by more than an order of magnitude and have led to the discovery of highly unusual supernovae. Observations of gamma-ray emission from 7–11 January 296 7–11 January 2013 Supernova SNRs with ground-based Cherenkov telescopes and the Fermi 2013 Supernova telescope have spawned new insights into particle acceleration in Raichak on Ganges, supernova shocks. Far-infrared observations from the Spitzer and Raichak Environmental Herschel observatories have told us much about the properties on Ganges, Calcutta, India Environmental and fate of dust grains in SNe and SNRs. Work with satellite-borne Calcutta, India Chandra and XMM-Newton telescopes and ground-based radio Impacts and optical telescopes reveal signatures of supernova interaction with their surrounding medium, their progenitor life history and of Impacts the ecosystems of their host galaxies. IAU Symposium 296 covers all these advances, focusing on the interactions of supernovae with their environments. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union Editor in Chief: Prof. Thierry Montmerle This series contains the proceedings of major scientifi c meetings held by the International Astronomical Union. Each volume contains a series of articles on a topic of current interest in Supernova astronomy, giving a timely overview of research in the fi eld. With contributions by leading scientists, these books are at a level Environmental Edited by suitable for research astronomers and graduate students. -

Stellar Evolution

Stellar Astrophysics: Stellar Evolution 1 Stellar Evolution Update date: December 14, 2010 With the understanding of the basic physical processes in stars, we now proceed to study their evolution. In particular, we will focus on discussing how such processes are related to key characteristics seen in the HRD. 1 Star Formation From the virial theorem, 2E = −Ω, we have Z M 3kT M GMr = dMr (1) µmA 0 r for the hydrostatic equilibrium of a gas sphere with a total mass M. Assuming that the density is constant, the right side of the equation is 3=5(GM 2=R). If the left side is smaller than the right side, the cloud would collapse. For the given chemical composition, ρ and T , this criterion gives the minimum mass (called Jeans mass) of the cloud to undergo a gravitational collapse: 3 1=2 5kT 3=2 M > MJ ≡ : (2) 4πρ GµmA 5 For typical temperatures and densities of large molecular clouds, MJ ∼ 10 M with −1=2 a collapse time scale of tff ≈ (Gρ) . Such mass clouds may be formed in spiral density waves and other density perturbations (e.g., caused by the expansion of a supernova remnant or superbubble). What exactly happens during the collapse depends very much on the temperature evolution of the cloud. Initially, the cooling processes (due to molecular and dust radiation) are very efficient. If the cooling time scale tcool is much shorter than tff , −1=2 the collapse is approximately isothermal. As MJ / ρ decreases, inhomogeneities with mass larger than the actual MJ will collapse by themselves with their local tff , different from the initial tff of the whole cloud. -

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

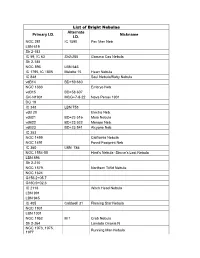

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var.