Medieval Trade Routes in the Kadapa Basin: a Study of Chitvel Taluka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geomorphological Studies of the Sedimentary Cuddapah Basin, Andhra Pradesh, South India

SSRG International Journal of Geoinformatics and Geological Science (SSRG-IJGGS) – Volume 7 Issue 2 – May – Aug 2020 Geomorphological studies of the Sedimentary Cuddapah Basin, Andhra Pradesh, South India Maheswararao. R1, Srinivasa Gowd. S1*, Harish Vijay. G1, Krupavathi. C1, Pradeep Kumar. B1 Dept. of Geology, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa-516005, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract: The crescent shaped Cuddapah basin located Annamalai Surface - at an altitude of over 8000’ (2424 mainly in the southern part of Andhra Pradesh and a m), ii. Ootacamund Surface – at 6500’-7500’ (1969- little in the Telangana State is one of the Purana 2272 m) on the west and at 3500’ (1060m) on the east basins. Extensive work was carried out on the as noticed in Tirumala hills, iii. Karnataka Surface - stratigraphy of the basin, but there is very little 2700’-3000’ (Vaidynathan, 1964). 2700-3300 reference (Vaidynathan,1964) on the geomorphology of (Subramanian, 1973) 2400-3000 (Radhakrishna, 1976), the basin. Hence, an attempt is made to present the iv. Hyderabad Surface – at 1600’ – 2000’v. Coastal geomorphology of the unique basin. The Major Surface – well developed east of the basin.vi. Fossil Geomorphic units correspond to geological units. The surface: The unconformity between the sediments of the important Physiographic units of the Cuddapah basin Cuddapah basin and the granitic basement is similar to are Palakonda hill range, Seshachalam hill range, ‘Fossil Surface’. Gandikota hill range, Velikonda hill range, Nagari hills, Pullampet valley and Kundair valley. In the Cuddapah Basin there are two major river systems Key words: Topography, Land forms, Denudational, namely, the Penna river system and the Krishna river Pediment zone, Fluvial. -

Hand Book of Statistics

HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS Y.S.R. DISTRICT 2018 CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER Y.S.R. DISTRICT Sri C. Hari Kiran,I.A.S., Collector & DistrictMagistra te, Y.S.R.District P R E F A C E The District Hand Book of Statistics 2018 in its 30th edition contains information of various Departments in the District including data relating to Agriculture, Rainfall and Land Utilization etc., I hope this book will be useful to the Public, Planners, Research Scholars, Bankers, Administrators and Non-Governmental Organizations. The continuous and generous co-operation extended by the District Officers in supplying the data for bringing out this publication is specially acknowledged. The Officers and Staff of the Chief Planning Office working in the District have done a commendable job in bringing out this publication. District Admi nistration welcomes the constructive suggestions and additional information for improvement of this Hand Book. DISTRICTCOLLECTOR, Y.S.R. DISTRICT, KADAPA. OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION Sl.No Name of the Officer Designation 1 Sri. V. THIPPESWAMY CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER 2 T. BASAVARAJU DEPUTY DIRECTOR 2 Sri. G.V. SWARUP KUMAR STATISTICAL OFFICER 3 Sri. R.PRABHAKAR RAO DY. STATISTICAL OFFICER I N D E X TABLE CONTENTS PAGE Nos. NO. A SALIENT FEATURES OF THE DISTRICT : NARRATIVE PART I – XXIII B COMPARISION OF THE DISTRICT WITH THE STATE 2017-18 XXIV – XXVIII C ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS IN THE DISTRICT – 2017-18 XXIX – XXX C (1) MUNICIPAL INFORMATION IN THE DISTRICT - 2017-18 XXXI D PUBLIC REPRESENTATIVES / NON-OFFICIALS XXXII – XXXVII PROFILE OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY / ASSEMBLY E XXXVIII - XLIII CONSTITUENCY 1 - POPULATION 1.1 VARIATION IN POPULATION, 1901 TO 2011 1 1.2 POPULATION STATISTICS, SUMMERY 2001 AND 2011 2 MANDAL WISE NO. -

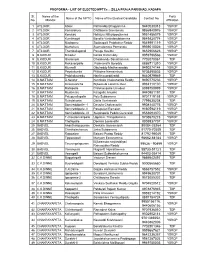

Sl. No. Name of the Mandal Name of the MPTC Name of the Elected

PROFORMA - LIST OF ELECTED MPTCs :: ZILLA PRAJA PARISHAD, KADAPA Sl. Name of the Party Name of the MPTC Name of the Elected Candidate Contact No No. Mandal Affiliation 1 ATLOOR Atloor Pothireddy Bhagyamma 9440030313 YSRCP 2 ATLOOR Kamalakuru Chittiboina Sreeramulu 9866940976 YSRCP 3 ATLOOR Konduru Nelaturu Nithyapoojamma 9951486079 YSRCP 4 ATLOOR Kumbhagiri Bandila Venkatasubbamma 9849828774 YSRCP 5 ATLOOR Madapuru Sodinapalli Prabhakar Reddy 9849991119 YSRCP 6 ATLOOR Muthukuru Syamalamma Ponnavolu 9959010026 YSRCP 7 ATLOOR Thamballagondi Perugu Savithri 9652906623 YSRCP 8 B.KODUR B.Kodur Konda Ramireddy 9959796566 YSRCP 9 B.KODUR Itharampet Chatakondu Sanathamma 7702070061 TDP 10 B.KODUR Mekavaripalle Padmavathi Boreddy 8886711310 YSRCP 11 B.KODUR Munnelli Obulreddy Madhavareddy 9490274144 YSRCP 12 B.KODUR Payalakuntla Pilliboina Narasimhulu 9703490503 YSRCP 13 B.KODUR Prabhalaveedu Neelima peddireddi 9440979949 TDP 14 B.MATTAM D.Nelatur Kunchala Vivekananda Reddy 9490770236 YSRCP 15 B.MATTAM Dirasavancha Bijivemula Lakshmi Devi 9963110130 YSRCP 16 B.MATTAM Mallepalle Chilekampalle Umadevi 8099750999 YSRCP 17 B.MATTAM Mudamala Kalagotla Anusha 9440981191 TDP 18 B.MATTAM Palugurallapalle Polu Subbamma 9701719158 YSRCP 19 B.MATTAM Rekalakunta Obilla Venkataiah 7799630208 TDP 20 B.MATTAM Somireddipalle -1 Devarla Chakravarthi 9908140775 YSRCP 21 B.MATTAM Somireddipalle -II Pasupuleti Ramaiah 9160594119 YSRCP 22 B.MATTAM Somireddipalle -III Sugalapalle Pedda Guravaiah 9553693370 YSRCP 23 B.MATTAM T.choudarivaripalle Uppaluri. Thirupalamma -

Are You Suprised ?

Chapter 2 Physical features 2.1 Geographical Disposition The Pennar (Somasila) – Palar - Cauvery (Grand Anicut) link canal off takes from the existing Somasila reservoir located across the Pennar River near Somasila village in Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh state. The link canal is proposed to pass through the Kaluvaya, Rapur, Dakkili, Venkatagiri mandals of Nellore district; Srikalahasti, Thottambedu, Pitchattur and Nagari mandals of Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh state, Tiruttani taluk of Tiruvallur district; Arakonam taluk of Vellore district; Cheyyar and Vandavasi taluks of Tiruvannamalai district; Kancheepuram, Uthiramerur taluks of Kancheepuram district; Tindivanam, Gingee, Villupuram, Tirukoilur taluks of Villupuram district; Ulundurpettai, Vridhachalam, Tittagudi taluks of Cuddalore district; Udaiyarpalayam, Ariyalur taluk of Perambalur district; and Lalgudi taluk of Tiruchchirappalli district of Tamil Nadu state.The link canal alignment passes through Pennar basin, Streams between Pennar and Palar basins, Palar basin and streams between Palar and Cauvery basins. The link canal takes off from the right flank of Somasila dam with a full supply level of 95.420 m. and runs parallel on right side of the Kandaleru flood flow canal, upto RD 10 km. The canal generally runs in south direction till it out-falls into Grand Anicut across Cauvery River at RD 529.190 km. The major rivers that would be crossed by the canal are Swarnamukhi, Arani Ar, Nagari, Palar, Cheyyar, Ponnaiyar, and Vellar. The districts that would be benefited by the link canal through enroute irrigation are Nellore, Chittoor of Andhra Pradesh state and Tiruvallur, Kancheepuram, Vellore, Tiruvannamalai, Villupuram, Cuddalore districts of Tamil Nadu state and Pondicherry (U.T). -

Village Statistics, Cuddapah District, Andhra Pradesh

OENSUS OF 1921 VILLAGE STATISTICS CUDDAPAH DISTRICT MADRAS PRESIDENOY MADRAS PRINTED 'SY THE BUPERINTE~DENTf GOVERNMENT PRESS 1921 CENSUS OF 1921. VILLAGE STATEMEN1". B.ADVEl.l TJ\LUK. 2 POPULATION. RELIGION _._--;-__-;- __ I------~---~~ Namea of villages. GOvernment. 1 1 Akkalareddipalle 193 945 497 448 719 121 105 2 .AkkemgundJa ... Uninha bited. 3 .Ankanagodugunlll' 55 251 121 130 198 15 88 4 Anantal'iijapul'am 373 ],825 934 I 891 1,815 9 1 6 Badvel (Rural) 130' 512 243 269 495 17 6 Badvel Town ... 1,153 5,246 2,6191 2,627 4,069 1,158 19 Baa.l/et 961 4,:362 2,193 I 2,169 3,236 1,112 G_tapaZZi 192 884 426 I 45'3 833 46 , .- 525::' 257 406' -38 7 Biiliiyapalle ... '.', 111 268 _. :t ~ .~:: -- 8 Bayyanapalli '" 44 209 102 I 107 209 9 Boppapuram 34 172 84 I 88 121 51 10 Budaveda 29 142 76 . 66 107 35 11 Chennupalli '" 97 463 245 218 331 5 127 12 Ohennamapalli 372 1,685 862 823 1,592 82 11 13 Oherlopalli ... 764 3,671 _1,835 1,836 3,143 42; ]01 140 Chinna Erasala 328 1,505 741 764 1,341 148 ]6 15 Ohintalachel'uvn 121 501 I 266 235 412 89 16 Dammanapalli .. 174 722 350 I 372 705 2 15 17 Diguvanelatul' .. 197 769 371 398 720 15 34 IS DiguvatambaUapaUi ... 49 233 no 123 197 13 23 19 Diraslloyantsa ... 303 1,449 751 698 1,258 129 62 20 Dulamvaripalli .... 54 224 114- 110 134 90 I .. -

Integrated Hydrological Data Book

INTEGRATED HYDROLOGICAL DATA BOOK (NON-CLASSIFIED RIVER BASINS) HYDROLOGICAL DATA DIRECTORATE INFORMATION SYSTEMS ORGANISATION WATER PLANNING & PROJECTS WING CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION NEW DELHI September, 2006 INTEGRATED HYDROLOGICAL DATA BOOK (NON-CLASSIFIED RIVER BASINS) HYDROLOGICAL DATA DIRECTORATE INFORMATION SYSTEMS ORGANISATION WATER PLANNING & PROJECTS WING CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION NEW DELHI SEPTEMBER, 2006 ABBREVIATIONS G : Gauge Sites GD : Gauge & Discharge sites GDS : Gauge, Discharge & Sediment sites GDQ : Gauge, Discharge and Water Quality Sites GDSQ : Gauge, Discharge, Sediment and Water Quality Sites Sq Km : Square Kilometers 0C : Degree Centigrade mm : Millimeters MCM : Million Cubic Meter N.A. : Not Applicable W YEAR : Water Year cumec : Cubic Meter per Second mhos/cm : Micro mhos per Centimeter + : Cation - : Anion ppm : Part per million m.e./litre : Milli equivalent per Litre pH : Negative logarithm of hydrogen ion concentration DO : Dissolved Oxygen BOD : Bio-Chemical Oxygen Demand Sod % age : Sodium percentage SAR : Sodium Absorption Ratio RSC : Residual Sodium Carbonate MPN : Most Probable Number mg/l : Milligram per Litre max : Maximum min : Minimum WQ : Water Quality m : Meter TDS : Total Dissolved Solids SNR : Sample Not received NF : No flow RD : River Dry Q : Water Discharge per Second CWC : Central Water Commission C O N T E N T S Sl.No. Table No. Topics Page No. 1 Section-I Description of Different River Basins Table No. 1.1 Salient Features of Different River Basins. Table No. 1.2 Number of Hydrological Observation Sites in Different River Basins. Table No. 1.3 Live Storage Capacity in Respect of Different River Basins. Table No. 1.4 Sitewise Important Historical Observations for Different River Basins. -

Dr. Ranjana Gupta M.A., B.Ed., Ph.D

The Elementary Geography Class 5 Based on the Syllabus Prepared by INTER-STATE BOARD FOR ANGLO-INDIAN EDUCATION, NEW DELHI The Elementary Geography Class 5 Dr. Ranjana Gupta M.A., B.Ed., Ph.D. (C.U.) S. CHAND SCHOOL BOOKS (An imprint of S. Chand Publishing) A Division of S. Chand & Co. Pvt. Ltd. 7361, Ram Nagar, Qutab Road, New Delhi-110055 Phone: 23672080-81-82, 9899107446, 9911310888; Fax: 91-11-23677446 www.schandpublishing.com; e-mail : [email protected] Branches : Ahmedabad : Ph: 27541965, 27542369, [email protected] Bengaluru : Ph: 22268048, 22354008, [email protected] Bhopal : Ph: 4274723, 4209587, [email protected] Chandigarh : Ph: 2725443, 2725446, [email protected] Chennai : Ph. 28410027, 28410058, [email protected] Coimbatore : Ph: 2323620, 4217136, [email protected] (Marketing Office) Cuttack : Ph: 2332580; 2332581, [email protected] Dehradun : Ph: 2711101, 2710861, [email protected] Guwahati : Ph: 2738811, 2735640, [email protected] Haldwani : Mob. 09452294584 (Marketing Office) Hyderabad : Ph: 27550194, 27550195, [email protected] Jaipur : Ph: 2219175, 2219176, [email protected] Jalandhar : Ph: 2401630, 5000630, [email protected] Kochi : Ph: 2378740, 2378207-08, [email protected] Kolkata : Ph: 22367459, 22373914, [email protected] Lucknow : Ph: 4076971, 4026791, 4065646, 4027188, [email protected] Mumbai : Ph: 22690881, 22610885, [email protected] Nagpur : Ph: 2720523, 2777666, [email protected] Patna : Ph: 2300489, 2302100, [email protected] Pune : Ph: 64017298, [email protected] Raipur : Ph: 2443142, Mb. : 09981200834, [email protected] (Marketing Office) Ranchi : Ph: 2361178, Mob. 09430246440, [email protected] Siliguri : Ph: 2520750, [email protected] (Marketing Office) Visakhapatnam : Ph: 2782609 (M) 09440100555, [email protected] (Marketing Office) ©Dr. -

Jurisdiction of Nellore Central Excise and Service Tax Commissionerate

Page 1 Annexure-A to Trade Notice No: 1 /2014 dated 07/10/2014 of Visakhapatnam Zone Jurisdiction of Nellore Central Excise and Service Tax Commissionerate Commissionerate Jurisdiction In the Revenue Districts of Dr.Y.S.Rajasekhara Reddy Kadapa District, Sri Potti Sriramulu NELLORE Nellore District and Prakasam District in the State of Andhra Pradesh Sl. Name of the Jurisdiction of the Division Name of the Jurisdiction of the Range No. Division Range The revenue Mandals of Kadapa, Brahmamgari matam, Chintakommadinne, Chennur, Khazipet, Badvel, Porumamilla, KADAPA Kalasapadu, Kasinayana, Sidhout, Gopavaram, Atluru, Ontimitta, Valluru, B.Koduru and Pendlimarri of Kadapa District The revenue Mandals of Proddatur, Rayachoti, T.Sundupalli, Lakkireddypalli, Ramapuram, Chakrayapet, Galivedu, Peddamudium, PRODDATUR Vempalli, Duvvuru, Sambepalli, Vemula, Jammalamadugu, Mylavaram, Chapadu, Mydukur, Kamalapuram, Veerapunayunipalli, In the Revenue District of Veeraballi, Rajupalem and Chinnamandem of Kadapa District Kadapa Division Dr.Y.S.Rajasekhara Reddy 1 (Central Excise Kadapa in the State of Andhra The revenue Mandals of Pulivendula, Lingala, Tonduru, Muddanuru, & Service Tax) CHILAMKUR Pradesh Simhadripuram, Kondapuram of Kadapa District. The revenue Mandals of Nandalur, Rajampet, Chitvel, Kodur, NANDALUR Pullampeta, Obulavaripalli and Penagaluru of Kadapa District. YERRAGUNTLA The entire Yerraguntla revenue Mandal of Kadapa District SERVICE TAX Entire Dr.Y.S.Rajasekhara Reddy Kadapa Revenue District RANGE Page 2 Annexure-A to Trade Notice No: -

Global Journal of Engineering Science And

[Babu, 5(12): December2018] ISSN 2348 – 8034 DOI- 10.5281/zenodo.2531469 Impact Factor- 5.070 GLOBAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCE AND RESEARCHES SUBSURFACE DAMS ON RIVER BEDS AS ECO FRIENDLY AND ECONOMY FRIENDLY, A CASE STUDY IN THE RIVER BASINS OF YSR DISTRICT OF RAYALASEEMA, A.P., INDIA K. Raghu Babu*1 & P. L. K. Kiran Kumar2 *1Asst. Professor, Dept. of Geology, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa 2Senior Research Fellow, Dept. of Geology, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa ABSTRACT World present scenario needs a multitasking technology that provides safety to living beings, environment and cost effective. One such technology attracting interest of Engineering scientists is construction of subsurface dams. Arid and semi-arid regions in general and YSR district of Rayalaseema region of Andhra Pradesh, India in particular have seasonal rivers which flow during monsoons and get dried during the other seasons. The salient principle behind the subsurface dams is that the flood water is trapped within the voids between the sand particles. Hence location having more coarse grained sand is suitable for the construction of such dams across the sand rivers. Subsurface dams trap water in the sand upstream of the dam wall, built across a sandy dry riverbed to a height of 0.4 m below the surface of the sand because, the sand beds have evaporation losses until the water sinks below 0.4 m below the sand surface. The coarse grained sand store more water than the fine grained sand, as the coarse sand could produce upto 350 litres of water per cubic meter space resulting an extraction rate of 35% of the total volume of the sand.In the present study dry river beds of Papaghni river near Gandi village, Penneru river near Siddavatam village and Cheyyeru river course between Rayachoti-Rajampeta villages were mapped to locate suitable location for the subsurface dams. -

Badvel Assembly Andhra Pradesh Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/AP-124-0118 ISBN : 978-93-87415-11-9 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 168 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-17 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 18-19 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

Punjab Board Class 9 Social Science Textbook Part 1 English

SOCIAL SCIENCE-IX PART-I PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION BOARD Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar © Punjab Government First Edition : 2018............................ 38406 Copies All rights, including those of translation, reproduction and annotation etc., are reserved by the Punjab Government. Editor & Co-ordinator Geography : Sh. Raminderjit Singh Wasu, Deputy Director (Open School), Punjab School Education Board. Economics : Smt. Amarjit Kaur Dalam, Deputy Director (Academic), Punjab School Education Board. WARNING 1. The Agency-holders shall not add any extra binding with a view to charge extra money for the binding. (Ref. Cl. No. 7 of agreement with Agency-holders). 2. Printing, Publishing, Stocking, Holding or Selling etc., of spurious Text- book qua text-books printed and published by the Punjab School Education Board is a cognizable offence under Indian Penal Code. Price : ` 106.00/- Published by : Secretary, Punjab School Education Board, Vidya Bhawan Phase-VIII, Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar-160062. & Printed by Tania Graphics, Sarabha Nagar, Jalandhar City (ii) FOREWORD Punjab School Education Board, has been engaged in the endeavour to prepare textbooks for all the classes at school level. The book in hand is one in the series and has been prepared for the students of class IX. Punjab Curriculum Framework (PCF) 2013 which is based on National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005, recommends that the child’s life at school must be linked to their life outside the school. The syllabi and textbook in hand is developed on the basis of the principle which makes a departure from the legacy of bookish learning to activity-based learning in the direction of child-centred system. -

Pennar (Somasila) to Cauvery (Grand Anicut) Inter Basin Water Transfer Impact Assessment on Land Use/Land Cover Environment

Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2017, 9, 393-409 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jwarp ISSN Online: 1945-3108 ISSN Print: 1945-3094 Pennar (Somasila) to Cauvery (Grand Anicut) Inter Basin Water Transfer Impact Assessment on Land Use/Land Cover Environment S. V. J. S. S. Rajesh, B. S. Prakasa Rao, K. Niranjan Dept. of Physics, Dr. L. B. College, Dept. of Geo-engineering, Andhra University College of engineering, Department of Physics, Andhra University, Visakhapatanam, Andhra Pradesh, India How to cite this paper: Rajesh, S.V.J.S.S., Abstract Prakasa Rao, B.S. and Niranjan, K. (2017) Pennar (Somasila) to Cauvery (Grand Ani- As a part of the National Water Development Authority (NWDA) proposal, cut) Inter Basin Water Transfer Impact the linking between Pennar and Cauvery is put forth with a single purpose of Assessment on Land Use/Land Cover Envi- conserving water to the maximum extent possible. The present study covers ronment. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 9, 393-409. with land use/land cover (LU/LC) along the alignment study area 17215.68 https://doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2017.94026 sq∙km. All the details of these features have been studied using IRS-P6, LISSIII data to analyze the effect of land use and land cover. The land use and land Received: February 11, 2017 cover data are classified into 9 categories such as crop land, current fallow, Accepted: March 28, 2017 Published: March 31, 2017 forest, plantations, built-up land, water bodies, scrub land, sandy area and others. The total area going to be capsized is 17215.68 sq∙km out of which Copyright © 2017 by authors and 10105.96 sq∙km is proposed command area.