A Region in Transition Politics and Power in the Pacific Island Countries S E I R T N U O C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picture As Pdf Download

MJA Centenary — History of Australian Medicine A history of health and medical research in Australia Timothy Dyke ealth and medical research has signifi cantly con- BVSc, PhD, MBA Summary Executive Director, tributed to improvements in human health and Health and medical research has played an important Strategic Policy Group H wellbeing throughout the world, and Australia has role in improving the life of Australians since before Warwick P Anderson played its part. As a result of this research, Australians have the 20th century, with many Australian researchers PhD benefi ted by remaining healthier for longer through better contributing to important advances both locally and Chief Executive Officer internationally. treatments and improved health care, and from contribu- National Health and Medical tions to national wealth through the development of in- The establishment of the National Health and Medical Research Council, Research Council (NHMRC) to support research and Canberra, ACT. novative industries. Despite the signifi cant role of research to work to achieve the benefi ts of research for the timothy.dyke@ in Australia, there have been few specifi c compilations on community was signifi cant. nhmrc.gov.au the Australian history of health and medical research. This The NHMRC has also provided guidance in research and article is a brief overview of Australian health and medical health ethics. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00347 research, with the role of the National Health and Medical Australian research has broadened to include basic Research Council (NHMRC) as a main focus. biomedical science, clinical medicine and science, public health and health services. The early years In October 2002, the NHMRC adopted Indigenous health research as a strategic priority. -

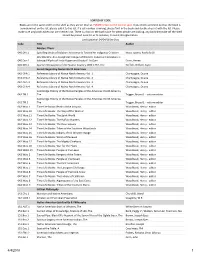

Ranching Catalogue

Catalogue Ten –Part Four THE RANCHING CATALOGUE VOLUME TWO D-G Dorothy Sloan – Rare Books box 4825 ◆ austin, texas 78765-4825 Dorothy Sloan-Rare Books, Inc. Box 4825, Austin, Texas 78765-4825 Phone: (512) 477-8442 Fax: (512) 477-8602 Email: [email protected] www.sloanrarebooks.com All items are guaranteed to be in the described condition, authentic, and of clear title, and may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Purchases are shipped at custom- er’s expense. New customers are asked to provide payment with order, or to supply appropriate references. Institutions may receive deferred billing upon request. Residents of Texas will be charged appropriate state sales tax. Texas dealers must have a tax certificate on file. Catalogue edited by Dorothy Sloan and Jasmine Star Catalogue preparation assisted by Christine Gilbert, Manola de la Madrid (of the Autry Museum of Western Heritage), Peter L. Oliver, Aaron Russell, Anthony V. Sloan, Jason Star, Skye Thomsen & many others Typesetting by Aaron Russell Offset lithography by David Holman at Wind River Press Letterpress cover and book design by Bradley Hutchinson at Digital Letterpress Photography by Peter Oliver and Third Eye Photography INTRODUCTION here is a general belief that trail driving of cattle over long distances to market had its Tstart in Texas of post-Civil War days, when Tejanos were long on longhorns and short on cash, except for the worthless Confederate article. Like so many well-entrenched, traditional as- sumptions, this one is unwarranted. J. Evetts Haley, in editing one of the extremely rare accounts of the cattle drives to Califor- nia which preceded the Texas-to-Kansas experiment by a decade and a half, slapped the blame for this misunderstanding squarely on the writings of Emerson Hough. -

The American West C1835-C1895

Ecclesfield School History Department The American West c1835-c1895 History GCSE (9-1) Revision Booklet This topic is tested on Paper 2, with the Elizabeth topic The exam lasts for 1 hour and 45 minutes There are 32 marks for American West (Section A) You should spend 50 minutes on this section Paper 2 1h45: American West and Elizabeth (8th June, PM) Name:________________________ History Teacher: ________________ 1 The American West, c1835-c1895 What do I need to know for this topic? Key Details Red Amber Green topic (Need to (Nearly (Nailed revise a there) it) lot) • Plains Indians: beliefs and way of life (survival, land and war) • The Permanent Indian Frontier (Indian Removal Act 1830) and the Indian Appropriations Act (1851) • Migration: Oregon Trail (1836 onwards), California Gold Rush (1849) • Migration: Donner Party and Mormons (1846-7) • The development and problems of white settlement farming • Reasons for conflict and tension between settlers and Indians – the Fort Laramie 62 Treaty (1851) - The early settlement of the West, of the settlement early The • Problems of lawlessness and attempts to tackle this 1. 1. c1835 • Significance of the Civil War and post-war reconstruction (Homestead Act 1862, Pacific Railroad Act 1862, First Transcontinental Railroad 1869) • Homesteaders’ solutions to problems: new technology, the Timber Culture Act 1873 and spread of the railroad • Continued problems of law and order • The cattle industry (Iliff, McCoy, 76 - Goodnight, the significance of Abilene) • The impact of changes in ranching -

SORTED by CODE Books Are in the Same Order on the Shelf As They Are on This List

SORTED BY CODE Books are in the same order on the shelf as they are on this list. PLEASE return to the correct spot. If you check someone out but the book is somehow not on the list, please add it to this list. If a call number is wrong, please fix it in the book and double check it with the list. Please make sure any books taken out are checked out. There is a box on the back table for when people are looking, any book they take off the shelf should be placed here for us to reshelve, to avoid disorganization. Last Updated: 04/04/18 by Grey Code Title Author Masters Thesis 040.DIN.1 Spiralling Webs of Relation: Movements Toward An Indigenist Criticism Nova, Joanne Rochelle Di Worldeaters: An Ecosophical Critique of Western Industrial Civilization in 040.Dun.1 Selected Works of Linda Hogan and Ursula K. Le Guin Dunn, Aimee 040.GRI.1 Spanish Occupation of the Hasinai Country 1690-1737, The Griffith, William Joyce Serials Regarding Native North Americans 042.CHA.1 Reference Library of Native North America Vol. 1 Champagne, Duane 042.CHA.2 Reference Library of Native North America Vol. 2 Champagne, Duane 042.CHA.3 Reference Library of Native North America Vol. 3 Champagne, Duane 042.CHA.4 Reference Library of Native North America Vol. 4 Champagne, Duane Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas: North America, 042.TRI.1 The Trigger, Bruce G. - volume editor Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas: North America, 042.TRI.2 The Trigger, Bruce G. -

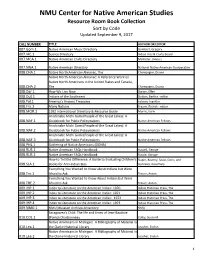

NMU Center for Native American Studies Resource Room Book Collection Sort by Code Updated September 9, 2017

NMU Center for Native American Studies Resource Room Book Collection Sort by Code Updated September 9, 2017 CALL NUMBER TITLE AUTHOR OR EDITOR 007.Gom.1 Native American Music Directory Gombert, Gregory 007.IAC.1 Source Directory Indian Arts & Crafts Board 007.MCA.1 Native American Crafts Directory McAlister, Diane L. 007.NNA.1 Native American Directory National Native American Coorperative 008.CHA.1 Native North American Almanac, The Champagne, Duane Native North American Almanac: A Reference Work on Native North Americans in the United States and Canada, 008.CHA.2 The Champagne, Duane 008.Dar.1 How We Live Now Darion, Ellen 008.Dut.1 Indians of the Southwest Dutton, Bertha - editor 008.Fol.1 America's Ancient Treasures Folsom, Franklin 008.Fra.1 Many Nations Frazier, Patrick - editor 008.MOR.1 1992 International Directory & Resource Guide Morris, Karin Anishinabe Michi Gami (People of the Great Lakes): A 008.NAF.1 Guidebook for Public Policymakers Native American Fellows Anishinabe Michi Gami (People of the Great Lakes): A 008.NAF.2 Guidebook for Public Policymakers Native American Fellows Anishinabe Michi Gami (People of the Great Lakes): A 008.NAF.3 Guidebook for Public Policymakers Native American Fellows 008.PHS.1 Gathering of Native Americans (GONA) 008.RUS.1 Native American FAQs Handbook Russell, George 008.RUS.2 Native American FAQs Handbook Russle, Geroge How to Tell the Difference: A Guide to Evaluating Children's Slapin, Beverly, Seale, Doris, and 008.SLA.1 Books for Anti-Indian Bias Gonzales, Rosemary Everything You Wanted -

Annual Review LETTER of TRANSMITTAL

2016 annual review LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL The Hon Susan Close MP Minister for Education and Child Development Minister for Higher Education and Skills Level 9, 31 Flinders Street Adelaide SA 5000 30 May 2017 Dear Minister, In accordance with the requirements of regulations under Part 4, Section 18 – Annual Report of the University of South Australia Act 1990, it gives me great pleasure to submit for your information and presentation to Parliament the University of South Australia 2016 Annual Review and the University of South Australia 2016 Financial Statements, for the year ending 31 December 2016. The University Council approved the Annual Review and the Financial Statements at its meeting on 13 April 2017. Yours sincerely, Mr Jim McDowell / Chancellor COMPANION VOLUME The University’s complete annual financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2016, adopted by the University Council are contained in the University of South Australia 2016 Financial Statements, a companion volume to this report. YOUR FEEDBACK We welcome any comments or suggestions on the content or layout of this report. Please contact the Corporate Communications Manager on: Telephone: +618 8302 9136 Email: [email protected] FURTHER INFORMATION This report and the University of South Australia 2016 Financial Statements, as well as past annual reports, are available on our website unisa.edu.au/publications ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY UniSA respects the Kaurna, Boandik and For hard copies of this report or the University of South Australia Barngarla peoples’ spiritual relationship 2016 Financial Statements, please contact: with their country. We also acknowledge Telephone: +618 8302 0657 the diversity of Aboriginal peoples, past Or write to: and present. -

Florey Medal Gene Therapy Tackles Leading Cause of Blindness in the Elderly

Vision News Autumn 2018 Florey Medal Gene therapy tackles leading cause of blindness in the elderly The pioneering scientist behind a potential new gene therapy treatment for a leading cause of blindness has won national recognition for her work. Professor Elizabeth Rakoczy has been awarded the 2017 CSL Florey Medal for significant lifetime achievement in biomedical science and/or human health advancement. She joins an elite list of past Florey Medallists including Nobel Laureates Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, Ian Frazer and Graeme Clark. Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt congratulates Professor Rakoczy at the Florey Medal presentation Professor Rakoczy, head of the Lions Eye (Photo credit: AAMRI/Brad Cummings Photography) Institute’s Molecular Ophthalmology research group, helped develop a new gene therapy for “The new gene therapy promises to replace wet age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD), monthly injections with a one-off treatment,” which leads to rapid vision loss and affects more Professor Rakoczy said. than 110,000 older Australians. “The gene therapy involves a single injection Wet AMD occurs when there is an overproduction of a modified and harmless version of a virus of the protein vascular endothelial growth factor containing a specific gene that stimulates supply (VEGF) in the retina. VEGF helps support oxygen of a protein which then blocks over-production supply to tissue when circulation is inadequate. of VEGF. The eye becomes a ‘bio-factory’ – When too much VEGF is produced it can cause producing its own treatment for wet AMD.” disease, including blood vessel disease in The gene therapy is not commercially available the eye. -

January 2015, There Was Also a Steampunk Vehicle May 2016, September 2016)

CONTENTS 3-4 COVER FEATURE Southern Missouri Rangers Fifth Annual Women’s Wild West Shootout 6-7 EDITORIALS How do we Stop the Loss of Members and Expand our Membership? Another Perspective Another Way of Looking at This SASS Divisional Championships Single Action Shooting Society® 8-9 COSTUMING CORNER 215 Cowboy Way, Edgewood, NM 87015 Wild Wild West and a Steampunk Convention 505-843-1320 • Fax 877-770-8687 © 2019 10-11 WILD BUNCH All rights reserved Oklahoma State Wild Bunch Championship 2018 The Cowboy Chronicle Magazine is Designed and Printed by 12-16 GUNS & GEAR The Single Action Shooting Society® Visit the SASS web site at: Dispatches From Camp Baylor—The Legend of “Heaven” and “Hell” www.sassnet.com BAMM Rifles 17-29 ANNUAL MATCHES EDITORIAL STAFF Rattlesnake Gulch Roundup 2018 Cowford Regulators 2018 Annual Match EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A Dark Day on The Santa Fe 2018 Skinny First Annual Shootout at The OK Corral SASS Pennsylvania State Championship 2018 MANAGING EDITOR Michigan State Championship Range War 2018 Misty Moonshine Appalachian Showdown XXVII EDITORS EMERITUS 30-35 PRODUCT REVIEW Cimarron’s Uberti 1858 Conversion Tex & Cat Ballou Swab-Its® Bore-Sticks™ ADVERTISING MANAGER 36-44 FICTION Square Deal Jim Small Creek: Kid Galena Rides—Chapter 9 410-531-5456 | [email protected] 45 HEALTH & FITNESS GRAPHIC DESIGN Stretching for Cowboy Action Shooters™ Mac Daddy 46-48 PROFILES 2018 Scholarship Recipient Diamond Kate, SASS #95104 STAFF WRITERS The Beginning of the End - Essay by Diamond Kate, SASS #95104 Big Dave, The Capgun Kid, Capt. George SASS Alias — Possibly the Best Part of the Game! Baylor, Col. -

Calls for Special Australian of the Year Award for Our Nation's Health Workers

Media Release Public Health Association of Australia 29 July 2020 Calls for special Australian of the Year Award for our nation’s health workers As Australia continues to battle our biggest-ever health crisis, The Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA) is calling for the Prime Minister to consider a special one-off award to recognise the life-saving work of our nation’s front-line health care workers and public health workers. Nominations for the 2021 Australian of the Year Awards close this week (Friday 31 July), and each year thousands of worthy individuals are nominated for going above and beyond in their chosen field or pursuits. PHAA CEO, Terry Slevin, says the events of the past six months have demonstrated the incredibly selfless work of the many thousands of people who have turned up for work every day – putting their own lives on the line in many cases – to help save the lives of so many fellow Australians. ‘It is in times like these that we see the best of people. People who dedicate their lives to the wellbeing of others in these times of terrible distress and tragic loss,’ Mr Slevin said. ‘The majority of our health workforce are not highly-paid. Few seek recognition or reward. They make so many personal sacrifices to keep us safe and well. And in the process, many hundreds have themselves succumbed to COVID-19,’ Mr Slevin said. ‘Our public health workers deserve a significant acknowledgement – the tireless work this year by contact tracers, researchers, epidemiologists, outbreak investigators and policy experts has been invaluable. -

Central Oregon Range Wars

Central Oregon Range Wars By Unknown Following the forced re-settlement of the region’s Indian groups onto reservations after the Civil War, the grasslands of Eastern and Central Oregon became available for agriculture and livestock. As “open ranges,” these lands were traditionally available for all locals to share. The 1880s and 1890s proved particularly suited to the development of large cattle herds and sheep flocks as new rail lines allowed producers to ship both wool and cattle to the expanding markets across the United States. As a result, the number of sheep and cattle east of the Cascades increased dramatically. Since no legal statutes existed at the time to restrict usage, the rapid, unregulated exploitation of the grasslands resulted in overgrazing. Between 1885 and 1910 the number of sheep in Wasco County was approximately 130,000. Given such numbers, the range was unable to regenerate itself, and became increasingly degraded. By the late 1890s, growing tensions between cattle ranchers and sheepmen over control of the open ranges led to a series of disputes known as the “range wars.” Cattlemen themselves held sheepmen in contempt for two specific reasons. Unlike cattle, sheep will eat weeds, also known as forbs, in addition to native grasses. As a result, the sheep stripped a landscape of its plant life, leaving nothing edible behind. Additionally, the equestrian culture of the cattlemen viewed sheepherders with disdain because the herdsmen tended animals on foot rather than on horseback. The expansion of wheat farming in Central and Eastern Oregon during this same period exacerbated competition for the range lands. -

In This Issue: Meet Our 2015 Alumni Award Recipients Women in Science Tribute to the Chancellor CONTACT

FOR ALUMNI AND COMMUNITY SUMMER 2015 In this issue: Meet our 2015 Alumni Award recipients Women in science Tribute to the Chancellor CONTACT CONTACT is produced by the Office of Marketing and Communications and UQ Advancement, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia Telephone: +61 (0)7 3346 7886 Email: [email protected] Website: uq.edu.au/uqcontact Advertising: Tina Cupitt Email: [email protected] Editorial Board: Shane Rodgers (Chair) – Queensland Editor, The Australian Graham Bethune – Director, Office of Marketing and Communications Colleen Clur – Senior Director, Communications and Engagement, Children’s Health Queensland Doctor John Desmarchelier AM ED – Former General Manager, Sugar Terminals Limited Clare Pullar – Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Advancement) Editors: Prue McMillan and Mark Schroder Project coordinators: Michael Jones and Stacey King Design: Paul Thomas Contributors: Bronwyn Adams, Meredith Anderson, Sally Belford, Renae Bourke, Amanda Briggs, Patricia Danver, Joseph Diskett, Reggie Dutt, Dr Maggie Hardy, Bruce CELEBRATING Ibsen, Fiona Kennedy, Danielle Koopman, Martine Kropkowski, EXCELLENCE Professor Jenny Martin, Dr John Montgomery, Associate Professor Meet the outstanding and inspirational Neil Paulsen, Katrina Shimmin- recipients of The University of Clarke, Professor Maree Smith, John Queensland Alumni Awards 2015. Story AO, Matthew Taylor, Professor Ranjeny Thomas, Evan Williams, 12 Genevieve Worrell. Material in this publication does not necessarily reflect the policies of The University of Queensland. CHANGE OF ADDRESS: + REGULARS + FEATURES Please telephone: +61 (0)7 3346 3900 Facsimile: +61 (0)7 3346 3901 Email: [email protected] UPDATE Printing: DAI Rubicon New Director of Alumni and FOR ALUMNI AND COMMUNITY WINTER 2015 07 LEADING THE WORLD Community Relations PatriciaWITH Danver RESEARCH This product is printed on PEFC BREAKTHROUGHS Ranked well inside the world’s top 100, The University of Queensland (UQ) is one of Australia’s leading teaching discusses strengthening UQ’sand research institutions. -

Health Care Professionals' Perceptions of Treatments for Co-Occurring Disorders

THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu B.S., Brigham Young University, Hawaii, 2008 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in EDUCATION (Multicultural Education) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO FALL 2010 THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT A Project by Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Forrest Davis, Ph.D. Date ii Student: Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. , Graduate Coordinator Dr. Maria Mejorado Date Department of Bilingual and Multicultural Education iii Abstract of THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT by Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu This project was oriented towards a study of the emic worldview of the Tongan population in Sacramento. The data that was collected in this study was utilized as a frame of reference for the curriculum. The lesson plans in the project are based upon the Single Study approach in multicultural education. This approach was utilized because the members of the Tongan populations have specific educational needs to be addressed in the process of acculturation into American Society. __________________________________, Committee Chair Forrest Davis, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to say “MALO ‘AUPITO” to Dr. Forrest Davis for his continual encouragement, refining, and persistency in following up my project.