The Euro-Dollar Market: an Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Version: July 6, 2017 MY PAPERS in ECONOMICS: an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Edmar Bacha1

1 This version: July 6, 2017 MY PAPERS IN ECONOMICS: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Edmar Bacha1 1. Introduction Since the mid-1960s, I have written extensively on development economics, the economics of Latin America and Brazil’s economic problems. My papers include essays on persuasion and reflections on economic policy-making experiences. I review these contributions roughly in chronological order not only because of the variety of topics but also because they tend to come together in specific periods. There are seven periods to consider, identified according to my main institutional affiliations: Yale University, 1964- 1968; ODEPLAN, Chile, 1969; IPEA-Rio, 1970-71; University of Brasilia and Harvard University, 1972-1978; PUC-Rio, 1979-1993; Academic research interregnum, 1994-2002; and IEPE/Casa das Garças since 2003. 2. Yale University, 1964-1968 My first published text was originally a term paper for a Master’s level class in international economics at Yale University. In The Strategy of Economic Development, Albert Hirschman suggested that less developed countries would be relatively more efficient at producing goods that required “machine-paced” operations. Carlos Diaz-Alejandro interpreted machine-paced as meaning capital-intensive 1 Founding partner and director of the Casa das Garças Institute of Economic Policy Studies, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. With the usual caveats, I am indebted for comments to André Lara- Resende, Alkimar Moura, Luiz Chrysostomo de Oliveira-Filho, and Roberto Zahga. 2 technologies, and tested the hypothesis that relative labor productivity in a developing country would be higher in more capital-intensive industries. He found some evidence for this. I disagreed with his argument. -

Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

risks Article Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data Long Hai Vo 1,2 and Duc Hong Vo 3,* 1 Economics Department, Business School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration, Quy Nhon University, Binh Dinh 560000, Vietnam 3 Business and Economics Research Group, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City 7000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Long-range dependency of the volatility of exchange-rate time series plays a crucial role in the evaluation of exchange-rate risks, in particular for the commodity currencies. The Australian dollar is currently holding the fifth rank in the global top 10 most frequently traded currencies. The popularity of the Aussie dollar among currency traders belongs to the so-called three G’s—Geology, Geography and Government policy. The Australian economy is largely driven by commodities. The strength of the Australian dollar is counter-cyclical relative to other currencies and ties proximately to the geographical, commercial linkage with Asia and the commodity cycle. As such, we consider that the Australian dollar presents strong characteristics of the commodity currency. In this study, we provide an examination of the Australian dollar–US dollar rates. For the period from 18:05, 7th August 2019 to 9:25, 16th September 2019 with a total of 8481 observations, a wavelet-based approach that allows for modelling long-memory characteristics of this currency pair at different trading horizons is used in our analysis. -

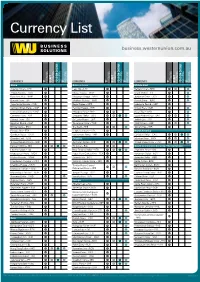

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

The Conflicting Developments of RMB Internationalization: Contagion

Proceeding Paper The Conflicting Developments of RMB Internationalization: Contagion Effect and Dynamic Conditional Correlation † Xiangqing Lu and Roengchai Tansuchat * Center of Excellence in Econometric, Faculty of Economics, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Presented at the 7th International Conference on Time Series and Forecasting, Gran Canaria, Spain, 19–21 July 2021. Abstract: As the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer, China has made exchange rate stability a top priority for its economic growth. With development over decades, however, China now holds excess dollar reserves that have suffered a huge paper loss because of quantitative easing in the United States. In this reality, China has been provoked into speeding RMB internationalization as a strategy to reduce the cost and get rid of the excessive dependence on the US dollar. Thus, this study attempts to investigate the volatility contagion effect and dynamic conditional correlation among four assets, namely China’s onshore exchange rate (CNY), China’s offshore exchange rate (CNH), China’s foreign exchange reserves (FER), and RMB internationalization level (RGI). Considering the huge changes before and after China’s “8.11” exchange rate reform in 2015, we separate the period of study into two sub-periods. The Diagonal BEKK-GARCH model is employed for this analysis. The results exhibit large GARCH effects and relatively low ARCH effects among all periods and evidence that, before August 2015, there was a weak contagion effect among them. However, after September 2015, the model validates a strengthened volatility contagion within CNY and CNH, CNY and RGI, Citation: Lu, X.; Tansuchat, R. -

British Banks in Brazil During an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930)* Prepared For: European Banks in Latin America During

British Banks in Brazil during an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930)* Prepared for: European Banks in Latin America during the First Age of Globalization, 1870-1914 Session 102 XIV International Economic History Congress Helsinki, 21 August 2006 Gail D. Triner Associate Professor Department of History Rutgers University New Brunswick NJ 08901-1108 USA [email protected] * This paper has benefited from comments received from participants at the International Economic History Association, Buenos Aires (2002), the pre-conference on Doing Business in Latin America, London (2001), the European Association of Banking History, Madrid (1997), the Conference on Latin American History, New York (1997) and the Anglo-Brazilian Business History Conference, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (1997) and comments from Rory Miller. British Banks in Brazil during an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930) Abstract This paper explores the impact of the British-owned commercial banks that became the Bank of London and South America in the Brazilian financial system and economy during the First Republic (1889-1930) coinciding with the “classical period” of globalization. It also documents the decline of British presence during the period and considers the reasons for the decline. In doing so, it emphasizes that globalization is not a static process. With time, global banking reinforced development in local markets in ways that diminished the original impetus of the global trading system. Increased competition from privately owned banks, both Brazilian and other foreign origins, combined with a static business perspective, had the result that increasing orientation away from British organizations responded more dynamically to the changing economy that banks faced. -

The Renminbi's Ascendance in International Finance

207 The Renminbi’s Ascendance in International Finance Eswar S. Prasad The renminbi is gaining prominence as an international currency that is being used more widely to denominate and settle cross-border trade and financial transactions. Although China’s capital account is not fully open and the exchange rate is not entirely market determined, the renminbi has in practice already become a reserve currency. Many central banks hold modest amounts of renminbi assets in their foreign exchange reserve portfolios, and a number of them have also set up local currency swap arrangements with the People’s Bank of China. However, China’s shallow and volatile financial markets are a major constraint on the renminbi’s prominence in international finance. The renminbi will become a significant reserve currency within the next decade if China continues adopting financial-sector and other market-oriented reforms. Still, the renminbi will not become a safe-haven currency that has the potential to displace the U.S. dollar’s dominance unless economic reforms are accompanied by broader institutional reforms in China. 1. Introduction This paper considers three related but distinct aspects of the role of the ren- minbi in the global monetary system and describes the Chinese government’s actions in each of these areas. First, I discuss changes in the openness of Chi- na’s capital account and the degree of progress towards capital account convert- ibility. Second, I consider the currency’s internationalization, which involves its use in denominating and settling cross-border trades and financial transac- tions—that is, its use as an international medium of exchange. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used. -

How One Dollar Grew Over Time

MFS ADVISOR EDGESM INVESTING BASICS How One Dollar Grew Over Time mfs.com Stocks — historically, a good place for long-term investors Worldwide Despite the many national and international crises throughout the past 30 years, COVID-19 investing in stocks has kept investors on track in pursuing their long-term goals. pandemic N. Korea STOCK defies $21.11 world with missile testing Oil prices Oil prices War plunge at record to 5-year with Iraq levels 9/11 begins Looming US low Y2K terrorist S&P 500 and “Fiscal Cliff” concerns attacks Hurricanes Dow fall to crisis on US Corporate Katrina and 10-year lows Wilma Dow Asian accounting breaks economic scandals President turmoil US BONDS 5000, $5.53 Bush Soviet market signs Union “too high” CASH NAFTA $2.14 collapses INFLATION $1 $1.95 1/91 1/96 1/01 1/06 1/11 1/16 12/20 Source: SPAR, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Important risk considerations MARKET SEGMENT REPRESENTED BY IMPORTANT RISK CONSIDERATIONS Stocks Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Index1 Stocks: Common stocks generally provide an opportunity for more capital appreciation than fixed-income investments US Bonds Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index2 but are also subject to greater market fluctuations. US Bonds and Cash: Corporate bonds, US Treasury bills, and US Cash FTSE 3-month Treasury Bill Index3 government bonds fluctuate in value, but if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and a fixed principal value. Inflation Consumer Price Index4 Keep in mind that all investments, including mutual funds, carry a certain amount of risk including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. -

Foreign Exchange Training Manual

CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY BARCLAYS SOURCE: LEHMAN LIVE LEHMAN BROTHERS FOREIGN EXCHANGE TRAINING MANUAL Confidential Treatment Requested By Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc. LBEX-LL 3356480 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY BARCLAYS SOURCE: LEHMAN LIVE TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................... PAGE FOREIGN EXCHANGE SPOT: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 FXSPOT: AN INTRODUCTION TO FOREIGN EXCHANGE SPOT TRANSACTIONS ........... 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 2 WJ-IAT IS AN OUTRIGHT? ..................................................................................................... 3 VALUE DATES ........................................................................................................................... 4 CREDIT AND SETTLEMENT RISKS .................................................................................. 6 EXCHANGE RATE QUOTATION TERMS ...................................................................... 7 RECIPROCAL QUOTATION TERMS (RATES) ............................................................. 10 EXCHANGE RATE MOVEMENTS ................................................................................... 11 SHORTCUT ............................................................................................................................... -

Relationship Between Share Market and Foreign Exchange Market in India (A Brief Study) Raj Kumar, Research Scholar, [email protected] Contact-9728157609

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 12, December-2013 1070 ISSN 2229-5518 Relationship between share market and foreign Exchange market in India (A brief study) Raj Kumar, research Scholar, [email protected] Contact-9728157609 Abstract- St ock exchange and i nt er est rat e ar e t wo cruci al factors of economi c growth of a country. The impacts of interest rate on stock exchange provide important implications for monitory policy, risk management practices, financial securities valuation and government policy towards financial markets. Index terms- Ef f i ci ent market , M arket r et urn, I nt er est rat e, I nvest ment 1 Introduction THIS share market and foreign exchange market both are vital elements of a financial system. Stock market is a place where shares are issued and traded either through exchange or over the counter markets. Also known as Equity market, it is one of the most vital areas of market economy as it provides companies with access to capital and investors with a slice of ownership in the company and the potential of gains based on the company’s future performance, whereas the foreign exchange market in which participants are able to buy, sell, exchange and speculate on currencies. Foreign exchange markets are made up of banks, commercial companies, central banks, investment management firms, hedge funds and retail forex brokers and investors. The forex market is considered to be the largest market in the world. India’s first Stock exchange was Bombay stock exchange established in 1875 in Bombay. -

Information Flows in Foreign Exchange Markets: Dissecting Customer Currency Trades

BIS Working Papers No 405 Information Flows in Foreign Exchange Markets: Dissecting Customer Currency Trades by Lukas Menkhoff, Lucio Sarno, Maik Schmeling and Andreas Schrimpf Monetary and Economic Department March 2013 (revised March 2016) JEL classification: F31, G12, G15 Keywords: Order Flow, Foreign Exchange Risk Premia, Heterogeneous Information, Carry Trades BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2016. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISSN 1020-0959 (print) ISSN 1682-7678 (online) Information Flows in Foreign Exchange Markets: Dissecting Customer Currency Trades LUKAS MENKHOFF, LUCIO SARNO, MAIK SCHMELING, and ANDREAS SCHRIMPF⇤ ABSTRACT We study the information in order flows in the world’s largest over-the-counter mar- ket, the foreign exchange market. The analysis draws on a data set covering a broad cross-section of currencies and di↵erent customer segments of foreign exchange end- users. The results suggest that order flows are highly informative about future ex- change rates and provide significant economic value. We also find that di↵erent customer groups can share risk with each other e↵ectively through the intermedia- tion of a large dealer, and di↵er markedly in their predictive ability, trading styles, and risk exposure.