Urbis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

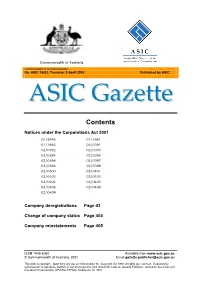

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002

= = `çããçåïÉ~äíÜ=çÑ=^ìëíê~äá~= = Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002 Published by ASIC ^^ppff``==dd~~òòÉÉííííÉÉ== Contents Notices under the Corporations Act 2001 00/2496 01/1681 01/1682 02/0391 02/0392 02/0393 02/0394 02/0395 02/0396 02/0397 02/0398 02/0399 02/0400 02/0401 02/0402 02/0403 02/0404 02/0405 02/0406 02/0408 02/0409 Company deregistrations Page 43 Change of company status Page 404 Company reinstatements Page 405 ISSN 1445-6060 Available from www.asic.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia, 2001 Email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 5179AA, Melbourne Vic 3001 Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC Gazette ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002 Company deregistrations Page 43= = CORPORATIONS ACT 2001 Section 601CL(5) Notice is hereby given that the names of the foreign companies mentioned below have been struck off the register. Dated this nineteenth day of March 2002 Brendan Morgan DELEGATE OF THE AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Name of Company ARBN ABBOTT WINES LIMITED 091 394 204 ADERO INTERNATIONAL,INC. 094 918 886 AEROSPATIALE SOCIETE NATIONALE INDUSTRIELLE 083 792 072 AGGREKO UK LIMITED 052 895 922 ANZEX RESOURCES LTD 088 458 637 ASIAN TITLE LIMITED 083 755 828 AXENT TECHNOLOGIES I, INC. 094 401 617 BANQUE WORMS 082 172 307 BLACKWELL'S BOOK SERVICES LIMITED 093 501 252 BLUE OCEAN INT'L LIMITED 086 028 391 BRIGGS OF BURTON PLC 094 599 372 CANAUSTRA RESOURCES INC. -

Risk Assessments in Heritage Planning in New South Wales

The Johnstone Centre Report Nº 184 Risk Assessments in Heritage Planning in New South Wales A Rapid Survey of Conservation Management Plans written in 1997–2002 by Dirk HR Spennemann Albury 2003 © Dirk H.R. Spennemann 2003 All rights reserved. The contents of this book are copyright in all countries sub- scribing to the Berne Convention. No parts of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author, except where permitted by law. CIP DATA Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (1958–) Risk Assessments in Heritage Planning in New South Wales. A Rapid Survey of the Conservation Management Plans written in 1997–2002 / by Dirk H.R. Spennemann Johnstone Centre Report nº 184 Albury, N.S.W.: The Johnstone Centre, Charles Sturt University 1v.; ISBN 1 86467 136 X LCC HV551.A8 S* 2003 DDC 363.34525 1. Emergency Management—Australia—New South Wales; 2. Historic Preservation—Australia—New South Wales; 3. Historic Preservation—Emergency Management ii Contents Contents ...................................................................................................iii Introduction..............................................................................................4 Methodology............................................................................................5 The Sampling Frame.....................................................................5 Methodology..................................................................................5 -

Campbelltown Local Government Area Heritage Review for Campbelltown

CAMPBELLTOWN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA HERITAGE REVIEW FOR CAMPBELLTOWN CITY COUNCIL VOLUME 1: REPORT APRIL 2011 Section 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS Page 1 Executive summary ...................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction .................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Background ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Report structure ................................................................................................. 3 2.3 The study area ................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Sources ............................................................................................................. 8 2.5 Method .............................................................................................................. 8 2.6 Limitations ......................................................................................................... 9 2.7 Background to the investigation of potential heritage items ................................ 9 2.8 Author Identification ......................................................................................... 10 2.9 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 10 3 Historical Context of the Campbelltown LGA ............................................. 11 3.1 Sources and background -

LANDSCAPES at RISK LIST Updated

LANDSCAPES AT RISK LIST Updated 30 October 2020: ’Watch & Action’ List Namadgi National Park, south of Canberra, on fire, seen from Mt. Ainslie 1/2020 (photo: Anne Claoue-Long) ACT/Monaro/Riverina Branch WATCH • Berry township and landscape setting, Shoalhaven – historic town Berry was part of the 1822 Coolangatta Estate formed by Alexander Berry and partner, Edward Wollstonecraft. Its 40,000- acre holding was prime dairy land, which much of the landscape remains. However rising tourist trade, day and weekend visitors/owners from Sydney, highway bypass upgrades and a Council that seems to under-value its real ‘asset’ – this lush farming landscape, as sharp contrast to its town boundaries, are eroding its integrity. There is a risk of precedent in approvals, leading to piecemeal strip development south to Bomaderry and ‘sprawl’ as rural blocks are bought, and subdivisions not-otherwise-permitted in zonings are approved, somehow. Similar pressures beset Milton and Kangaroo Valley townships in their respective landscape settings. The National Trust of Australia (NSW) have classified the Berry District Landscape Conservation Area for its heritage values, but it lacks legal protection, serious planning and heritage leadership, vigilance and active management. English ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’ classification is one option – strict zoning as ‘rural’ with non-variable minimum lot size, strict urban boundaries; • Australian War Memorial $498m expansion – near-doubling its floor space, with building bulk intruding into the (above) vista from Mt. Ainslie south over the lake to the parliamentary AUSTRALIAN GARDEN HISTORY SOCIETY LANDSCAPES AT RISK 30 October 2020 1 triangle. Approval based on insufficient study, analysis and assessment of its surrounding landscape and a poor heritage listing description has led to inadequate protection for its landscape. -

LANDSCAPES at RISK LIST Updated 15 May 2021: 'Watch & Action'

LANDSCAPES AT RISK LIST Updated 15 May 2021: ’Watch & Action’ List Namadgi National Park, south of Canberra, on fire, 1/2020 seen from Mt. Ainslie (photo: Anne Claoue-Long) ACT/Monaro/Riverina Branch WATCH o Yarralumla former Forestry School 1926+ campus of the Australian Forestry School, located in Westbourne Woods to capitalise on dendrology, mensuration, surveying and soils instruction using differing tree species planted 1914-24 by Charles Weston. Many of those trees are now ending their lifespans, but still serve as link to this early stage of ‘modern’ Canberra. In 1965 Forestry transferred to ANU, but the Commonwealth Forestry & Timber Bureau and the Forest Research Institute stayed here until CSIRO took over the site in 1975. CSIRO withdrew from forest research c2008. In 2002 the lease on the now 11ha precinct was sold by the Howard government to the Shepherd Foundation, who provide services to deaf children. CSIRO was allowed to sub-lease for 20 years, until 2022. The Shepherd Foundation have begun exploring ways to re-develop the land as a source of finance. Consultations with residents and community groups are underway. ACT Branch of AGHS will tour the site in February 2021. o Bungendore Diggers’ pines (?1920s), Gibraltar Street, Mick Sherd Oval Monterey pines (Pinus radiata) grown from seed brought back by Diggers. Issue with Queanbeyan Palerang Council cutting down over 13 that over the last 5 years. The trees are acknowledged in the War AUSTRALIAN GARDEN HISTORY SOCIETY LANDSCAPES AT RISK 7 Feb. 2021 1 Memorial registers. There has never been any acknowledgement by council of their significance or purpose and no replacement option or plans other than a few Japanese elms. -

Function and Exterior Design of Verandaed Colonial Houses in New South Wales

The Otemon Journal of Australian Studies, vol. ῑ῎,pp.῏ΐ῏ ῌ ῏ῐ, ῐ῎῎ῒ ῌ῍ῌ Function and Exterior Design of Verandaed Colonial Houses in New South Wales Miki Watanabe Ashikaga Institute of Technology ῌ ῌ Purpose and Methods Verandaed houses are the most “Australian” of all colonialῌtime architecture, re- flecting distinct characteristics closely associated with its climate and environments. We certainly get the impression looking at the exterior views. And in Australia, Ve- randaed colonial house have acquired their originality through gradual development. Although Australians have been active in conducting research, measurement sur- veys, and renovation or conservation of historic buildings+῍, few analysis have been done comparing specific case examples. Thus it is important in the sense that we reῌdiscover the identity of colonial houses in Australia, which has been generally overlooked. This is a study on houses of the early colonial period ῌbetween ῏ and ῏ΐ῎῍ in New South Wales. The purpose of this study is to clarify their specific charac- teristics from the following key points : ῏ ῍ To analyze the role of the veranda by classifying floor plan shapes based on how verandas are connected to the main building. ῐ ῍ To analyze the role of exterior design by classifying roof style based on the relationship between house and veranda. For the analysis subjects, I used ῒ῏ case examples of verandaed houses from a ῏ ῍ Dr. James Broadbent remarked in his doctoral thesis “Aspect of Domestic Architectures in NSW ῏ ῌ ῏ῒῑ” on the characteristic examples of Australian colonial houses : The main conditions are French doors, smallῌscale, symmetry, hipped roof, oneῌstory building, sin- gle housing, a mildlyῌinclined roof, the building unified with the veranda roof or roof of the main house and minimum use of decoration. -

Fernhill Estate

Fernhill Estate Conservation Management Plan October 2019 Prepared for NSW Department of Planning, Industry & Environment Suite C2.09 22-36 Mountain Street Ultimo NSW 2007 Tel: (02) 9211 2212 www.jpad.com.au Nominated Architect Jennifer Preston. Registration number 6596. Registered Business Name JPA&D Australia Pty Ltd. ACN 100 865 585 ABN 32 100 865 585 Fernhill Estate Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 6 1.1 Sites for this Study 6 1.2 Summary Statement of Significance 6 1.3 Key Findings 7 1.4 Critical Recommendations 7 2.0 Introduction 9 2.1 Outline of Tasks Required to be Undertaken in Brief 9 2.2 Definition of the Study Area/Item 9 2.3 Methodology 11 2.4 Limitations 11 2.5 Identification of Authors 11 2.6 Acknowledgments 11 3.0 Documentary Evidence 12 3.1 Thematic History 12 3.2 Chronology of Development 61 3.3 Historical Themes 67 3.4 Ability to Demonstrate 69 4.0 Physical Evidence 70 4.1 Identification of Existing Fabric 70 4.2 Analysis of Existing Fabric 142 4.3 Assessment of Archaeological Potential 145 4.4 Assessment of Views and Vistas 146 5.0 Assessment of Cultural Significance 150 5.1 Comparative Analysis 150 5.2 Definition of Curtilage 154 5.3 Statement of Significance 156 5.4 Review against State Heritage Register Criteria 157 5.5 Grading of Significance 160 6.0 Constraints and Opportunities 192 6.1 Issues arising from the Statement of Significance 192 6.2 Issues Arising from the Physical Condition 192 6.3 Heritage Management Framework 193 6.4 Opportunities for Use 199 6.5 Statutory and Non-Statutory Listings 204 6.6 Conserving the Natural Environment 204 6.7 Managing the Cultural Landscape 205 7.0 Development of Conservation Policy 211 7.1 Introduction 211 8.0 Conservation Policies and Guidelines 215 8.1 Definitions 215 8.2 Policies 215 9.0 Implementing the Plan 235 9.1 Policy Implementation 235 10.0 References 237 10.1 Heritage advice 237 10.2 Unpublished sources 237 10.3 Internet sources 237 JPA&D Australia Pty Ltd. -

Camden Historic Cultural Heritage Assessment 20.09.12

BIOSIS R E S E A R C H Camden Gas Project Amended Northern Expansion: Historic Cultural Heritage Assessment Report for AGL Upstream Investments Pty. Ltd. October 2012 Natural & Cultural Heritage Consultants 8 Tate Street Wollongong 2500 BIOSIS R E S E A R C H Ballarat: 506 Macarthur Street Ballarat, VIC, 3350 Ph: (03) 5331 7000 Fax: (03) 5331 7033 email: [email protected] Brisbane: 72A Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, QLD, 4006 Ph: (07) 3831 7400 Fax: (07) 3831 7411 email: [email protected] Canberra: Unit 16 / 2 Yallourn Street, Fyshwick, ACT, 2609 Ph: (02) 6228 1599 Fax: (02) 6280 8752 email: [email protected] Melbourne: 38 Bertie Street, Port Melbourne, VIC, 3207 Ph: (03) 9646 9499 Fax: (03) 9646 9242 email: [email protected] Sydney: 18-20 Mandible Street, Alexandria, NSW, 2015 Ballarat: Ph: (02) 9690 2777 Fax: (02) 9690 2577 email: [email protected] 449 Doveton Street North Ballarat3350 Wangaratta: 26a Reid Street, Wangaratta, VIC, 3677 Ph: (03) 5331 7000 Fax: (03) 5331 7033 Ph: (03) 5721 9453 Fax: (03) 5721 9454 Email: [email protected] Queanbeyan: Wollongong: 8 Tate Street Wollongong, NSW, 2500 Ph: (02) 4229 5222 Fax: (02) 4229 5500 55 Lorn Road Queanbeyan 2620 email: [email protected] Ph: (02) 6284 4633 Fax: (02) 6284 4699 Project no: s5252 / 11944/13343/14975 BIOSIS RESEARCH Pty. Ltd. A.C.N. 006 075 197 Author: Fenella Atkinson Pamela Kottaras Asher Ford Reviewer: Melanie Thomson Peter Woodley Mapping: Robert Suansri Ashleigh Pritchard Biosis Research Pty. Ltd. This document is and shall remain the property of Biosis Research Pty. -

S60666 V3 Cover.Cdr

Camden Gas Project, Northern Expansion: Part 3A Historic Cultural Heritage Assessment, NSW 2010 FINAL FIGURES BIOSIS RESEARCH 98 MountMount WilsonWilsonBilpinBilpin TaranaTarana MountMount WilsonWilsonBilpinBilpin WoyWoy WoyWoy HartleyHartley MountMount VictoriaVictoria WindsorRichmondWindsorRichmond WindsorWindsor BerowraBerowra HamptonHampton BlackheathBlackheath OberonOberon KatoombaKatoomba MonaMona ValeVale HornsbyHornsby PenrithPenrith BlacktownBlacktown BlacktownBlacktown EppingEpping ChatswoodChatswoodManlyManly BlackBlack SpringsSprings JenolanJenolan CavesCaves ParramattaParramatta MulgoaMulgoa WallaciaWallacia StrathfieldStrathfield SydneySydney BankstownBankstownLiverpoolLiverpool SydneySydney HurstvilleHurstville .. SutherlandSutherland NarellenNarellen CamdenCamden CampbelltownCampbelltown MenangleMenangle PictonPicton AppinAppin BuxtonBuxton BargoBargo BellambiBellambi PointPoint Bioregions (IBRA ver. 6.1) TaralgaTaralga Sydney Basin WollongongWollongong South Eastern Highlands MyrtlevilleMyrtleville MittagongMittagong BowralBowral PortPort KemblaKembla MossMoss ValeVale 00 1010 2020 3030 4040 kilometreskilometres (((( (((( (((( (((( LEPPINGTONLEPPINGTON (( (( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( (((( MDENMDENMDEN VALLEY VALLEYVALLEY WAY WAYWAY MDENMDENMDEN VALLEY VALLEYVALLEY WAY WAYWAY (((( (((( (((( CACACA (((( CACACA (((( GEORGESGEORGESGEORGESGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVER RIVER RIVER RIVER CACACA GEORGESGEORGESGEORGESGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVERGEORGES RIVER RIVER RIVER RIVER CACACA GEORGESGEORGESGEORGESGEORGES -

Macarthur Memorial Park 166-176 St Andrews Road, Varroville

Development Application Macarthur Memorial Park 166-176 St Andrews Road, Varroville Visual Assessment Report prepared for: Catholic Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust by: Dr. Richard Lamb September, 2017 1/134 Military Road, Neutral Bay, NSW 2089 PO Box 1727 Neutral Bay NSW 2089 T 02 99530922 F 02 99538911 E [email protected] W www.richardlamb.com.au Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 3 1.1 Background and purpose of this report 3 1.2 Documents consulted 4 1.3 Signifi cance of the Scenic Hills to this report 5 1.4 Study by Paul Davies and Geoff rey Britton 7 2.0 Visual exposure of the Site 9 2.1 Long range views 9 2.2 Medium range views 9 2.3 Close range views: roads 9 2.4 Close range views: residential areas 17 2.5 Summary of visual exposure 17 2.6 Visual sensitivity 18 2.7 Opportunities 19 3.0 Photomontages and certifi cation 20 3.1 Purpose of this section of the report 20 3.2 Visual impact study by Virtual Ideas 20 3.3 Role of RLA in reviewing View Impact Study by VI 22 3.4 Specifi c objectives for RLA in this report 22 3.5 Limitations 22 3.6 Principles of verifi cation of photomontages 23 3.7 Focal length of lens for photographs 23 3.8 Checking the montage accuracy 24 3.9 Assumptions made in rendering photorealistic images 24 3.9 View location documentation 25 3.10 Certifi cation of photomontages 25 3.11 Analysis of the photomontages 25 4.0 The DA in relation to visual impacts 28 4.1 Staging of the proposed development 28 4.2 Visual resources 29 4.3 How does the DA protect the visual resources? 29 4.4 Summary on principles for conserving -

Heritage Council Report 2000

Heritage Council of NSW Annual Report 1999 - 2000 FROM THE CHAIR In December 1999 I completed my first term as Chair of the Heritage Council. I was very pleased to agree to the Minister’s request to extend the appointment for a further two years. I have visited many more parts of the State in this role during the past year - places like Dubbo, Coolah, Cowra, Canowindra, Newcastle, Macquarie Marshes and Port Macquarie. I have also spoken to groups as diverse as the Royal Australian Historical Society, the Newcastle City Council and the National Trust. I have also attended launches and functions organised by the Heritage Office. And of course there have been many opportunities to spread the heritage message through the media. These visits, and the conversations and discussions that go with them, constantly reinforce my conviction that heritage does matter to most people. Most of us understand that we need to maintain and build on our connections with the past. Not for sentimental reasons, but because it is those connections that ground us in the here and now. We need them to make sense of our lives and our aspirations. I have been particularly pleased this year to see all the work in preparing the Heritage Curriculum Materials Project finally come to fruition with the distribution of these innovative units to all primary schools in the State. It is vital that cultural heritage forms a normal part of the school curriculum so that the rising generation of school students has a better understanding of the need to conserve and pass on to future generations the places and objects that are important to us. -

LANDSCAPES at RISK LIST Updated 16 April 2020

LANDSCAPES AT RISK LIST Updated 16 April 2020: ’Watch & Action’ List Namadgi National Park, south of Canberra, on fire, seen from Mt. Ainslie 1/2020 (photo: Anne Claoue-Long) ACT/Monaro/Riverina Branch WATCH • Australian Capital Territory Plan variation 369 – Living Infrastructure Plan tree cover controls – the territory government proposes 30% tree canopy cover and 30% permeable surfaces in urban areas. While laudable, plan detail says 15% (not 30) for medium density areas – precisely where green space and trees are the most precious. The branch made a submission recommending redrafting at 30% for all urban land. • Wingello Park, nr. Marulan – NSW Land & Environment Court appeal against refused DA to alter/extend – and local and state heritage listing nominations to NSW Heritage Council and Goulburn-Mulwaree Council. The branch has written supporting proposed local listing. • Australian National Botanic Garden, Acton – impacted by a dramatic hailstorm in January 2020, causing considerable damage and leaving parts of the garden closed to the public. • Namadgi Nature Reserve, south of Canberra – over half of its area was burnt in recent bushfires. AUSTRALIAN GARDEN HISTORY SOCIETY LANDSCAPES AT RISK 16 April 2020 1 • Eurobodalla Regional Botanic Gardens, S. of Batemans Bay – 1/3 burnt by wildfires in 1/2020. Buildings including recently expanded visitors’ centre unharmed. • Namadgi Nature Reserve, south of Canberra – over half of its area burnt in recent bushfires. • Bendora Arboretum, south of Canberra – burnt in recent bushfires – one of the few government- planted arboreta (experimental forestry planting trials) left after previous bushfire seasons. • Wandella Woods Arboretum, Cobargo – burnt out in December-January wildfire, house saved.