Hippies, Feminists, and Neocons: Using the Big Lebowski to Find the Political in the Nonpolitical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-6-2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Semenza, Timothy, ""The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen" (2012). Honors Scholar Theses. 241. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/241 Semenza 1 Timothy Semenza "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Semenza 2 Timothy Semenza Professor Schlund-Vials Honors Thesis May 2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Preface Choosing a topic for a long paper like this can be—and was—a daunting task. The possibilities shot up out of the ground from before me like Milton's Pandemonium from the soil of hell. Of course, this assignment ultimately turned out to be much less intimidating and filled with demons than that, but at the time, it felt as though it would be. When you're an English major like I am, your choices are simultaneously extremely numerous and severely restricted, mostly by my inability to write convincingly or sufficiently about most topics. However, after much deliberation and agonizing, I realized that something I am good at is writing about film. -

Elijah Siegler, Coen. Framing Religion in Amoral Order Baylor University Press, 2016

Christian Wessely Elijah Siegler, Coen. Framing Religion in Amoral Order Baylor University Press, 2016 I would hardly seem the most likely candidate to review a book on the Coen brothers. I have not seen all of their films, and the ones I saw … well, either I did not understand them or they are really as shallow as I thought them to be. With one exception: I did enjoy O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000). And I like A Serious Man (2009). So, two exceptions. And, of course, True Grit (2010) – so, all in all three exceptions1 … come to think of it, there are more that have stuck in my mind in a positive way, obfuscated by Barton Fink (1991) or Burn After Reading (2008). Therefore, I was curious wheth- er Elijah Siegler’s edited collection would change my view on the Coens. Having goog- led for existing reviews of the book that might inspire me, I discovered that none are to be found online, apart from the usual flattery in four lines on the website of Baylor University Press, mostly phrases about the unrivalled quality of Siegler’s book. Turns out I have do all the work by myself. Given that I am not familiar with some of the films used to exemplify some of this book’s theses, I will be brief on some chapters and give more space to those that deal with the films I know. FORMAL ASPECTS Baylor University Press is well established in the fields of philosophy, religion, theol- ogy, and sociology. So far, they have scarcely published in the media field, although personally I found two of their books (Sacred Space, by Douglas E. -

Et Tu, Dude? Humor and Philosophy in the Movies of Joel And

ET TU, DUDE? HUMOR AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE MOVIES OF JOEL AND ETHAN COEN A Report of a Senior Study by Geoffrey Bokuniewicz Major: Writing/Communication Maryville College Spring, 2014 Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Faculty Supervisor Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Division Chair Abstract This is a two-part senior thesis revolving around the works of the film writer/directors Joel and Ethan Coen. The first seven chapters deal with the humor and philosophy of the Coens according to formal theories of humor and deep explication of their cross-film themes. Though references are made to most of their films in the study, the five films studied most in-depth are Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and A Serious Man. The study looks at common structures across both the Coens’ comedies and dramas and also how certain techniques make people laugh. Above all, this is a study on the production of humor through the lens of two very funny writers. This is also a launching pad for a prospective creative screenplay, and that is the focus of Chapter 8. In that chapter, there is a full treatment of a planned script as well as a significant portion of written script up until the first major plot point. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter - Introduction VII I The Pattern Recognition Theory of Humor in Burn After Reading 1 Explanation and Examples 1 Efficacy and How It Could Help Me 12 II Benign Violation Theory in The Big Lebowski and 16 No Country for Old Men Explanation and Examples -

She's Baa-Aack!

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 17, 2018 5:15:56 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of March 25 - 31, 2018 She’s Roseanne Barr stars in baa-aack! “Roseanne” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Roseanne (Roseanne Barr, “The Roseanne Barr Show”) and Dan Conner (John Goodman, “The Big Lebowski, 1998”) return to the airwaves in the premiere of “Roseanne,” airing Tuesday, March 27, on ABC. A reboot of the classic comedy of the same name, the new series once again takes a look at the struggles of working class Americans. The rest of the original main cast returns as well, including Emmy winner Laurie Metcalf (“Lady Bird,” 2017). WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIES YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA We Need: SALES & SERVICE SPRING ALLERGIES ARE HERE! Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Alleviate your mold allergy this season! We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA www.newenglandallergy.com at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Thomas F. Johnson, MD, FACP, FAAAAI, FACAAI Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 17, 2018 5:15:57 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights CHANNEL Kingston (27) Atkinson Sunday 9:30 p.m. -

The Dude Abides": How the Big Lebowski Bowled Its Way from a Box Office Bombo T Nation-Wide Fests

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 2 Marginalia/Marginalities Article 6 12-4-2012 "The Dude Abides": How The Big Lebowski Bowled Its Way from a Box Office Bombo t Nation-Wide Fests Katarzyna Małecka University of Management, Łódź Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Małecka, Katarzyna. ""The Dude Abides": How The Big Lebowski Bowled Its Way from a Box Office Bomb to Nation-Wide Fests." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.2, 2020, pp. 76-93, doi:10.2478/v10231-012-0056-5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Volume 2 Number 2, 2012 DOI: 10.2478/v10231-012-0056-5 Katarzyna Małecka University of Management, Łódź “The Dude Abides”: How The Big Lebowski Bowled Its Way from a Box Office Bomb to Nation-Wide Fests A BSTRACT Since Blood Simple, the first film they wrote and directed together, the Coen Brothers have been working their way up in the film world and, in spite of their outside-the-mainstream taste for the noir and the sur- real, have earned a number of prestigious prizes. -

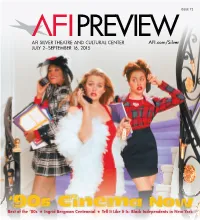

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Age 46

ISSUE 72 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER AFI.com/Silver JULY 2–SEPTEMBER 16, 2015 ‘90s Cinema Now Best of the ‘80s Ingrid Bergman Centennial Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York Tell It Like It Is: Contents Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 ........................2 July 4–September 5 Keepin’ It Real: ‘90s Cinema Now ............4 In early 1968, William Greaves began shooting in Central Park, and the resulting film, SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM: TAKE ONE, came to be considered one of the major works of American independent cinema. Later that year, following Ingrid Bergman Centennial .......................9 a staff strike, WNET’s newly created program BLACK JOURNAL (with Greaves as executive producer) was established “under black editorial control,” becoming the first nationally syndicated newsmagazine of its kind, and home base for a Best of Totally Awesome: new generation of filmmakers redefining documentary. 1968 also marked the production of the first Hollywood studio film Great Films of the 1980s .....................13 directed by an African American, Gordon Park’s THE LEARNING TREE. Shortly thereafter, actor/playwright/screenwriter/ novelist Bill Gunn directed the studio-backed STOP, which remains unreleased by Warner Bros. to this day. Gunn, rejected Bugs Bunny 75th Anniversary ...............14 by the industry that had courted him, then directed the independent classic GANJA AND HESS, ushering in a new type of horror film — which Ishmael Reed called “what might be the country’s most intellectual and sophisticated horror films.” Calendar ............................................15 This survey is comprised of key films produced between 1968 and 1986, when Spike Lee’s first feature, the independently Special Engagements ............12-14, 16 produced SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT, was released theatrically — and followed by a new era of studio filmmaking by black directors. -

The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Popular Culture American Studies 12-12-2008 The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers Mark T. Conard Marymount College Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Conard, Mark T., "The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers" (2008). American Popular Culture. 5. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_popular_culture/5 conard_coen_dj2:Layout 1 9/29/08 6:18 PM Page 1 CONARD (continued from front flap) FILM/PHILOSOPHY THE PHILOSOPHY OF systems. The tale of love, marriage, betrayal, and divorce THE PHILOSOPHY OF in Intolerable Cruelty transcends the plight of the charac- “The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers offers a very ters to illuminate competing theories of justice. Even in smart, provocative, and stylishly written set of lighter fare, such as Raising Arizona and The Big Lebowski, essays on the films of the Coen brothers. The THE COEN the comedy emerges from characters’ journeys to the volume makes a convincing case for reading their brink of an amoral abyss. However, the Coens often films within a wide array of philosophical contexts knowingly and gleefully subvert conventions and occa- and persuasively demonstrates that the films of sionally offer symbolic rebirths and other hopeful out- BROTHERS the Coen brothers often implicitly and sometimes comes. -

COLOURSOURS Surge in the Use of Strong and Playful Longer Purely to Serve As a Function, 2 Colours, Instead of Just Using Greys

31 John Goodman, Helen Mirren BRYANBRYANTATAKESKES and Bryan THETHE LEAD LEAD Cranston Not that anyone had any doubts Really, though, Trumbo’s over Bryan Cranston’s acting troubles are more significant and talents after five breathtaking not just for historical reasons. In Trumbo, Breaking Bad’s seasons on Breaking Bad, but now Cranston added: “The story of In Trumbo, Breaking Bad’s he has finally got a leading film Trumbo is really one of what BrBryayann Cranston Cranston stars starsasasaa role that shows them off. would you do to retain your civil His portrayal of school teacher liberties in a society that prides HollyHollywowoodod screenwriter screenwriter Walter White’s descent into a itself on its enlightenment and whose beliefs meant he wasn’t drugs kingpin while suffering advancement? whose beliefs meant he wasn’t from cancer earned him four “To all of a sudden have those creditedcreditedfoforr Oscar Oscar winning winning Golden Globe nominations, in- liberties taken away and demand cluding one win, and now his lead- under the penalty of incarcera- moviesmovies.V.Vibeibe’s’s JIMJIMPAPALMERLMER ing role in biopic Trumbo has tion, what affiliations do you have caughtcaught up up with with its its stars. stars... given the 59-year-old actor his politically, if you are religious FOOTLOOSE CLASSES first Oscar nod. what do you practice, are you gay, Fans of Footloose will be able to cut Released on February 5, Trumbo are you straight? unlike what happened then.” He said: “He tended to whip me, Gareth loose with a free line-dancing work- is the true story of screenwriter “The Nazis used that – where are You would be mistaken to think except he’d do it where he would- Gates shop in north Kent to tie in with the Dalton Trumbo whose left-wing all the Jews? – to persecute, to Trumbo is a straight-laced, stony- n’t show the marks.He was great. -

"You See, My Wife's Dad Is Real Well Off" -- Money Obscured in the Coen Brothers" (2019)

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2019 "You see, my wife's dad is real well off " -- Money Obscured in the Coen Brothers Sarah Mae Fleming [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fleming, Sarah Mae, ""You see, my wife's dad is real well off" -- Money Obscured in the Coen Brothers" (2019). Honors Projects Overview. 153. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/153 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “You see, my wife’s dad is real well off” – Money Obscured in the Coen Brothers Sarah Mae Fleming Undergraduate Honors Thesis Film 492 2 I am very interested in money. Not so much in the pursuit of large amounts of it, but more in the study of how money shapes our culture. Money is a crucial component to American identity. How we navigate our economic situation shapes us; it is deeply tied to important questions about race, gender, sexuality, religion, and citizenship. Particularly, I am drawn to the portrayal of money in film. In cinema, money can seem like it does not exist, such as in comedies or dramas, where characters have fully furnished, chic apartments with no sense of how these items could be afforded. Other times it is the driving force behind all narrative action; in crime or heist films that often center on large sums of money or a valuable artifact. -

On the Set Twitter Is Like... the Michael Cera Syndrome

01 29 10 | reportermag.com On The Set Of indie thriller, “Second Story Man” Twitter is Like... Six ways to describe the indescribable The Michael Cera Syndrome How long before he starts getting creepy? TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 29 10 | VOLUME 59 | ISSUE 17 NEWS PG. 06 Earthquake Hits Home For Rosmy Darisme A Haitian resident speaks about the tragedy in his homeland. RIT/ROC Forecast Go out there and be somebody. SG Update Freeze Fest is just around the corner. LEISURE PG. 10 The Psychology of Michael Scott What is that man thinking? Reviews Watch out pop music, The Dead Weather is coming for you. At Your Leisure Alex Rogala is in the house. FEATURES PG. 16 On the Set of “Second Story Man” An indie flick in the making. Twitter is like... Six ways to describe the indescribable. SPORTS PG. 22 Swim and Dive The Tigers take on two foes. Sarah Dagg Keep an eye out for #21. VIEWS PG. 27 The Michael Cera Syndrome How long before he starts getting creepy? RIT Rings Get a room! Rich Odlum (‘10) looks up to the summit of Mount Jo (Elevation 2876 ft) a peak in the Adirondak Park, while fellow students climb behind him. The students took part in a wellness class this past weekend named Adirondak Snowing, a part of RIT’s new Interactive Adventures program. | photograph by Steve Pfost Cover photograph by Chris Langer EDITOR’S NOTE EDITOR IN CHIEF Andy Rees | [email protected] HEISENBERG’S UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE MANAGING EDITOR Madeleine Villavicencio While doing research for this week’s feature (see pg. -

The Big Lebowski: the Dude's Lessons in Law and Leadership For

Pace Law Review Volume 37 Issue 1 Fall 2016 Article 6 March 2017 The Big Lebowski: The Dude’s Lessons in Law and Leadership for Military and National Security Attorneys Ryan A. Little Judge Advocate, United States Army Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Ryan A. Little, The Big Lebowski: The Dude’s Lessons in Law and Leadership for Military and National Security Attorneys, 37 Pace L. Rev. 191 (2017) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol37/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Big Lebowski: The Dude’s Lessons In Law And Leadership For Military And National Security Attorneys Major Ryan A. Little1 ABSTRACT The Big Lebowski is a cultural phenomenon that has prompted academic research into the nature of cult cinema, provided fodder for a host of law review quotes, and motivated a tradition of fan festivals and midnight screenings. However, most viewers do not realize that The Big Lebowski also serves as an engaging training tool for military and national security attorneys. Disguised as an impish play on film noir and hard-boiled detective fiction, The Big Lebowski’s unpretentious treatment of delicate topics contains poignant lessons for military and national security attorneys that include: (1) the risks facing national security attorneys when they lose focus on their professional and moral responsibilities, (2) the unexpected ways military attorneys should expect to encounter mental health concerns and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), (3) the importance of values and how they impact the success of a national security legal office, and (4) the role of the attorney in military operations.