Kunisada's Twelve Month Series, October 10, 2008-February 1, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Object Labels

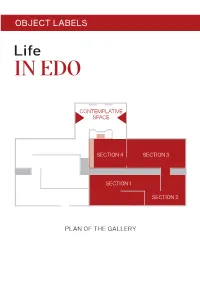

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-E and 20Th Century La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum Fall 2000 Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-E and 20th Century La Salle University Art Museum Caroline Wistar La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum and Wistar, Caroline, "Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-E and 20th Century" (2000). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 23. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAPANESE PRINTS UKIOY-E AND 20TH CENTURY LA SALLE UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM FALL 2000 We are much indebted to Mr. Benjamin Bernstein for his generous donation of Ukiyo-e prints and of Japanese sketch books from which the present exhibits have been drawn. SPECIAL EXHIBITION GALLERY JAPANESE “UKIYO-E” WOODCUT PRINTS This selection of Japanese woodcuts is all by “Ukiyo-e” artists who practiced during the sec ond half of the 19th century. “Ukiyo-e” refers to the “fleeting, floating” world of everyday life in Japan especially as experienced by those who serviced and patronized the licensed pleasure and entertainment districts found in all major cities of Japan. Such genre, which was depicted in paintings and books as well as woodcuts, de veloped in the mid 17th century in response to the need of the elite Samurai lords and the grow ing upper-middle class merchant to escape from the rigid confines of the ruling military dictator ship. -

Issue 3 Spring 2014

Issue 3 Inside this issue: Spring 2014 Editor’s Note 2 Upcoming Events 3 IAJS News: A summary of Japan-related academic events in 6 Israel Special Feature: Voices in Japanese Art Research in Israel 10 Featured Article: The Brush and the Keyboard: On Being an 13 Artist and a Researcher Collecting Japanese Erotic Art: Interview with Ofer Shagan 18 Japanese Art Collections in Israel 21 New Scholar in Focus: Interview with Reut Harari, PhD Candidate 29 at Princeton University New Publications: A selection of publications by IAJS members 32 The Israeli Association for Japanese IAJS Council 2012-2013 The Israeli Association of Studies Newsletter is a biannual Japanese Studies (IAJS) is a non publication that aims to provide Honorary President: -profit organization seeking to information about the latest Prof. Emeritus Ben-Ami encourage Japanese-related developments in the field of Japanese Shillony research and dialogue as well as Studies in Israel. (HUJI) to promote Japanese language education in Israel. We welcome submissions from IAJS Council Members: members regarding institutional news, Dr. Nissim Otmazgin (HUJI) For more information visit the publications and new researches in the Dr. Michal Daliot-Bul (UH) IAJS website at: Dr. Irit Averbuh (TAU) www.japan-studies.org Image: Itsukushima, Aki. Utagawa field of Japanese Studies. Please send Dr. Sigal Ben-Rafael Galanti Hiroshige II (1829-1869). Section of your proposals to the editor at: (Beit Berl College & HUJI) General Editor: Ms. Irit Weinberg emaki-mono, ink and colour on paper, [email protected]. Dr. Helena Grinshpun (HUJI) Language Editor: Ms. Nikki Littman 1850-1858. -

The 25 Most Important Classical Shunga Artists (Vol

Issue 04 12-2019 The 25 Most Important Classical Shunga Artists (Vol. 2) Issue 04 12-2019 The 25 Most The Important Classical Shunga 25 Most Artists (Vol. 2) Important Classical Shunga Artists (Vol. 2) On our forum (will be launched later this year!) and blog you can find much more exciting info about Hokusai. You can also check out other free eBooks in the following section! Issue 04 12-2019 Contents The 25 Most The 25 Most Important Classical Shunga Artists (Vol. 2) 7 Important Chōbunsai Eishi (1756-1829) 9 Classical Shunga Chōkyōsai Eiri (act. c. 1789-1801) 11 Artists Kikugawa Eizan (1787-1867) 13 (Vol. 2) Keisai Eisen ((1790-1848) 15 Yanagawa Shigenobu (1787-1832) 17 Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825 19 Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865) 21 Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) 23 Kawanebe Kyosai (1831-1889) 25 Tomioka Eisen (1864-1905) 27 Ikeda Terukata (1883-1921) 29 Mission 31 Copyright © 2019 On our forum (will be launched later this year!) and Design and lay out: Haags Bureau blog you can find First print: december 2019 much more exciting info about Hokusai. You can also No part of this publication may be reproduced and/or check out other published by means of printing, photocopying, microfilm, free eBooks in the scan, electronic copy or in any other way, without prior following section! permission from the author and publisher. Issue 04 12-2019 The 25 Most Important Classical Shunga Artists (Vol. 2) The 25 Most In our previous volume (both can be downloaded in our eBooks section) Important we examined the first 15 of the 25 most important shunga artists Classical Shunga ending with Kitao Masanobu. -

Japanese Prints of the Floating World

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current Honors College 5-8-2020 Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world Madison Dalton James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029 Part of the Acting Commons, Art Education Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Dalton, Madison, "Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world" (2020). Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current. 10. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savoring the Moon: Japanese Prints of the Floating World _______________________ An Honors College Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Visual and Performing Arts James Madison University _______________________ by Madison Britnell Dalton Accepted by the faculty of the Madison Art Collection, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors College. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Virginia Soenksen, Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Director, Madison Art Collection and Lisanby Dean, Honors College Museum Reader: Hu, Yongguang Associate Professor, Department of History Reader: Tanaka, Kimiko Associate Professor, Department of Sociology Reader: , , PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Honors Symposium on April 3, 2020. -

KABUKI ACTORS Masterpieces of Japanese Woodblock Prillts {Rom the Colleetioll of the Art Illstitute of Chicago

KABUKI ACTORS Masterpieces of japanese Woodblock Prillts {rom the Colleetioll of The Art Illstitute of Chicago abuki theater and Ukiyo-e prints developed side by side during the Edo period (1603-1868 ). Both Kwere designed ro appeal TO the newly prosperous urban merchant class in Edo (now modern-day Tokyo), Sakai, Osaka, and Kyoto. he Tokugawa shogunate (feudal government) had stratified most of Japanese society into four Tclasses: the samurai (warrior elite) at the higheST level, followed by farmers, artisans, and merchants. By the eighteenth century, this theoretical ordering of society no longer corresponded ro economic reality, as the merchant class had come to control a considerable proporrion of the nation's wealth. Denied access to political power, urban merchants spent their money lavishly on both culture and frivolity. This extravagant young culture became a separate world in itself, and was dubbed Ukiyo - tht!' " Floating World:' The word Ukiyo, which originally alluded to the Buddhist term for the transient "Sorrowful World," aptly characterized this e\'er-changing world of fashion and entertainment. oodblock printing, which produced inexpensive and therefore disposable images, was ideal for Wthe depiction of this fashionable and sensual city life. Many artists and publishing houses in the urban centers produced Ukryo-e ("Pictures of the Floating Wo rld") for a public whose tastes differed from, but were no less discriminating than, those of the aristocracy. Entertainment districts filled with brothels wefe licensed by the feudal government. These red-light districTS, along WiTh Kabuki theaters, Sumo wrestling rings, and restaurants, provided all manner of entertainment for the pleasure-seeking bourgeoisie. -

Utagawa Kuniyoshi's Depiction of Beautiful Women

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Depiction of Beautiful Women Nakazawa Mai This essay considers the stylistic characteristics of the bijinga pictures of beauties by the late Edo period ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). This ex- amination consisted of a comparison with the leading ukiyo-e bijinga artist of the day, his older studio mate Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1864), and an examination of how Kuniyoshi’s style was developed by his pupil Tsukio- ka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) who was active in the Meiji period. First, in the section titled 2. Changes in Kuniyoshi’s Bijinga Depiction, I focused on two factors, facial and body depiction, tracking the changes in characteristics and pictorial style across the works in each era, namely the Tenpô, Kôka and Kaei eras. As a result, the uniform depiction found in the Tenpô period was striking, while the Kôka era works show a sense of each woman’s indi- viduality and emotions, and by the Kaei era, there was a sense of a deepening of these features and as such, a broadening of how the beauties were depicted. This study also indicated that many of the women were quite well fleshed, bright in expression and depicted with a sense of vivacity. Continuing, 3. Comparison with Kunisada’s Works, shows that the Tenpô era Kuniyoshi was influenced by the beauty style of Kunisada, which was already popular at the time, and from the Kôka era onwards he established his own distinctive beauty style. Further, considering that Kuniyoshi then became renowned for his warrior prints while Kunisada for his actor prints, then we can indicate the possibility that their respective Kôka era and later bi- jinga were based on their respective specialty genres. -

Review of Amy Reigle Newland, the Commercial and Cultural Climate of Japanese Printmaking

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (History of Art) Department of the History of Art 12-2004 Review of Amy Reigle Newland, The Commercial and Cultural Climate of Japanese Printmaking Julie Nelson Davis University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/histart_papers Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Davis, J. (2004). Review of Amy Reigle Newland, The Commercial and Cultural Climate of Japanese Printmaking. Print Quarterly, 21 (4), 475-476. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/histart_papers/ 8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/histart_papers/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review of Amy Reigle Newland, The Commercial and Cultural Climate of Japanese Printmaking Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Asian Art and Architecture | History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology This review is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/histart_papers/8 Japanese Printmaking in Context JulieNelson Davis TheCommercial andCultural Climate ofJapanese Printmaking} thesixteen book titles and two print series produced by the editedby Amy Reigle Newland,Amsterdam, Hotei publisherUrokogataya Sanzaemon between 1670 and 1683, Publishing,2004, 272 pp., 18 col. and 53 b. & w.ills., €68.50. eight(possibly nine) titles were reissued in wholly or partial- lyreçut versions from 1683 onwards; they were presumably This bookbrings to a wideraudience the full-lengthlost through fire and thepublisher subsequently elected to papersoriginally presented at 'The HoteiPublishing First reissuethem. Yet some of the six publishers were apparent- InternationalConference on JapanesePrints', held at lymore fortunate - none of their inventory needed remanu- LeidenUniversity in January2000. -

Japanese Beauties Prints Exhibition

Japanese Beauties 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Japanese Beauties Japanese Beauties Sotheran’s are very pleased to have had the opportunity to put together this exhibition of Japanese Beauties prints. These are often referred to as Bijin-ga or “beautiful person pictures.” This is the first time we have done an exhibition solely dedicated to this genre. The artist most associated with this area of Japanese printmaking is Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806). There is a large collection of prints by Utamaro in the exhibition (items 34-65). There are both modern 20th Century versions as well as lifetime impressions available. These include a Museum quality piece (item 36) depicting the famous Courtesan Hanaogi. We are fortunate to have one print by Hasui Kawase (1883-1957) in the show (item 33). Kawase is among the most significant artists of the shin-hanga or “new prints” movement. There are some enchanting prints by Narita Morikane (items 77- 79). Very little is known about this artist except that he produced prints for a series titled “Twenty Four Figures of Charming Women.” We do hope you will be able to attend the exhibition which will take place in the Print department from Thursday 2nd May – Thursday 23rd May 2019. Note: All sizes given include acid free mounts unless otherwise stated. The one’s which are unmounted have paper size shown and can be mounted by request at no extra cost. 1. ANON. Maiko and the Yasaka Pagoda. 2. -

Life Is a Highway: Prints of Japan's Tokaido Road May 6, 2014

Life is a Highway: Prints of Japan’s Tokaido Road May 6, 2014 - August 17, 2014 Parallel Images for the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Edo Period (1615-1867), 1843-1847 Color woodcuts Museum purchase, gift of friends of the museum 2005.25.7.1-.58 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Kunisada Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1786 - 1865 Nihonbashi: Courtesan and Attendant Kanagawa: Female Fisher near the Urashima-zuka Utagawa Kuniyoshi Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Shinagawa: Shirai Gompachi Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Hodogaya: Shinozuka Hachiro Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1797-1858 Kawasaki: Nitta Yoshioki Totsuka: Goten-jochu Page 1 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Kuniyoshi Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Fujisawa: Ogura Kojiro and His Wife, Hakone: Soga no Goro Prepares for Vengeance Terute-no-hime Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1797-1858 Utagawa Hiroshige Mishima: Festival Dancers at the Oyama Zumi Japanese, 1797-1858 no Mikoto Temple Hiratsuka: Inage Saburo Shigenari Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Kuniyoshi Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Numazu: Travelers on the Road Oiso: Soga no Juro and the Oiran Tora Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1797-1858 Odawara: Yoritomo Minamoto is Admitted to Hara: Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Taketori the House of Masako monogatari) Page 2 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1798 - 1861 Japanese, 1797-1858 Yoshiwara: Fuji River, Mizushima Eijiri: Hagoromo no Matsu Utagawa Kuniyoshi Utagawa Hiroshige Japanese, 1798 -

Private Collection

private collection DH PRIVATE COLLECTION | Page 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 38. OCHIAI YOSHIIKU: NEWSPAPER - NICHINCHI SHIMBUN NO.978 53 DARYL HOWARD AND CLAUDE HOLEMAN 10 39. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: THE CHILD OF HORISAKA SAHEI 54 DR. RICHARD LANE AND CLAUDE HOLEMAN 11 40. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: MIKI TOYOKICHI 55 41. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: MOON AT SKUJAKU GATE 56 BIJUTSU SEKAI BOOKS AND CLAUDE HOLEMAN 78, 79 42. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: 100 ASPECTS OF THE MOON WITH FAN 57 PAUL JACOULET AND CLAUDE HOLEMAN 166, 167 43. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: KESA GOZEN 58 44. TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI: 100 ASPECTS OF THE MOON WITH GUITAR 59 45. TOYOHARA KUNICHIKA: JUSENRO - THIRTY-SIX MODERN RESTAURANT 60 46. TOYOHARA KUNICHIKA: TOKYO BOASTS SPECIALTY ASSOCIATION 61 CONTENTS 47. KOBAYASHI KIYOCHIKA: CHUSHINGURA, YURANOSUKE IN RETIREMENT 62 1. UNKNOWN: DEATH OF THE BUDDHA (PAINTING) 12 48. ADACHI GINKO: NOBLEMAN AND ROOFTOP GHOST 64 2. UNKNOWN ARTIST : BUDDHIST PRINT, MOUNTAIN GOD 13 49. ADACHI GINKO: SOGA BROTHERS ATTACKING SUKETSUNE 65 3. TORII KYIOMITSU: LACQUER PRINT 14 50. MIYAGAWA SHUNTEI: IRIS GARDEN IN JUNE 66 4. TOSA MITSUOKI 15 51. MIYAGAWA SHUNTEI: APRIL 68 5. SHUNSHO: AN EARLY SHUNSHO PRINT 16 52. OGATA GEKKO: #7: 36 PRINT SERIES 70 6. KATSUKAWA SHUNSHO : ONE HUNDRED POEMS BY ONE HUNDRED POETS 17 53. OGATA GEKKO: BENTEN SHRINE AT INOKASHIRA 71 7. UNKNOWN: KABUKI POSTER 18 54. OGATA GEKKO: THE DIVINE POWER OF FUDO AND THE NOVICE YUTEN 72 8. NAGAHIDE: OSAKA PRINT 19 55. OGATA GEKKO: HAYAMI TOZAEMON MITSUTAKA 73 9. KAWANABE GYOSAI: THE CROW (SUMI YE PAINTING ON PAPER) 20 56. OGATA GEKKO: HARA SOMEONE MOTOTOKI 74 10. -

Ōatari Kyōgen Inuki Tachihara

大 当 狂 言 The Great Master of Ukiyoe Kanshojo Kanshojo Inuki Tachihara Ōatari Kyōgen Inuki Tachihara Inuki Tachihara is recognized as the greatest woodblock artist alive today. A jazz saxophonist-turned-artist. Tachihara came across an ukiyo-e work which deeply moved him when he was 25 years old. For the past 33 years. he has dedicated himself to extensive scientific research on the types of paper and pigments used in the Edo era. and he has so far reproduced more than 70 ukiyo-e prints. In the Edo era, ukiyo-e prints were created by the combined efforts of the artist, the engraver and the printer. But Tachihara executes each laborious step of the process all by Akoya (by Tachihara) himself ̶ something unheard of in the past! Moreover, his reprints are so perfect that they have been assessed as“well- preserved first prints from the Edo era.” and museums around the world are paying close attention to his techniques. He is highly esteemed as an authority on the science of Edo colors and has presented a number of lectures on the colors used in ukiyo-e prints to societies in Japan and abroad. During the last decade. Tachihara has been concentrating his passion more on original works than reproductions. Part of the reason for this was his inability to obtain the types of paper and ink used in the Edo period. Recently, however, the combined efforts of a Japanese paper-making craftsman and an ink specialist have borne fruit: they have successfully reproduced the types of paper and ink used in the twilight years of shogunate rule.