Digibooklet Mozart Complete String Trios Jacques Thibaud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludwig Van Beethoven: the String Trios

Ludwig van Beethoven: The String Trios Sinae Baek, violin Cesia Corrales, viola Paul Christopher, cello Program Notes by Jackson Harmeyer Tonight’s program centers on the trios of Beethoven, and we hear two of these—numerically the first and the last in The genre of string trio was one which occupied Ludwig his catalogue. The String Trio in E-flat major, Opus 3, is van Beethoven for only a few years. All five of his trios for Beethoven’s earliest, published in 1796. Much like the trio violin, viola, and cello were written in the 1790s and by Mozart, which he had titled “Divertimento,” published in Vienna. Beethoven would write no further Beethoven’s Opus 3 is in six movements and follow his string trios after starting his impressive cycle of sixteen same pattern. Both trios begin with a fast first movement string quartets in 1798. Yet, alongside the one string trio which applies sonata principle; they continue with a slow produced by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the five created second movement, a minuet, another slow movement, and by Beethoven are regarded as the greatest works of their another minuet; and finally conclude with a fast sixth genre produced in the eighteenth century. Together they movement in rondo form. Beethoven even snatches mark the first pinnacle in this genre’s history, as Mozart’s conspicuous key signature of E-flat major, one Beethoven’s turn away from the string trio would prove which would have posed difficulties for string players of symptomatic of a larger trend: though the eighteenth that era. -

Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM BY LAURIE SHULMAN, ©2019 Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony ONE-MINUTE NOTES Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta This work demonstrates the enormous spectrum of sound color possible without woodwinds or brass. Treating piano, xylophone and celesta as pitched percussion and harp as part of the string family, Bartók mesmerizes us with hazy washes of sound and brilliant cloudbursts of exuberant joy. Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 A slow march in the first movement of this beloved symphony gains passion and momentum as it unfolds. The unforgettable Andante cantabile horn solo will touch your heart. Tchaikovsky’s waltz reminds us he was a great ballet composer, while his triumphant finale brings satisfying closure. BARTÓK: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sz. 106, BB 114 BÉLA BARTÓK Born: March 25, 1881, in Nagyszentmiklós, Transylvania (Hungary) Died: September 26, 1945, in New York, New York Composed: June to 7 September 1936 World Premiere: January 21, 1937, in Basel, Switzerland. Paul Sacher conducted the Basel Chamber Orchestra. NJSO Premiere: 1985–86 season. George Manahan conducted. Duration: 27 minutes As the shadow of Nazism lengthened over Europe in the mid-1930s, Béla Bartók dug in his heels philosophically. A fierce opponent of fascism, he categorically refused to perform concerts in Nazi Germany, and he declined even radio broadcast performances of his compositions in either Germany or Italy. At the same time, his fierce loyalty to his own country, and his love of Central Europe’s rich musical heritage, 2 resurfaced in his composition. Early in his career, he and his countryman Zoltán Kodály had conducted important ethnomusicological research into the folk music of remote sectors in Hungary, Slovakia and Romania. -

Triofenix String Trio Prograamme Suggestions

Photo Isabelle Pateer / Otherweyes Photo Isabelle Pateer TRIOFENIX STRING TRIO PROGRAAMME SUGGESTIONS In 2006, Shirly Laub (violin), Tony Nys (viola) and Karel Stey- invited to play with various eminent orchestras in Europe and Beethoven Trio, op. 9 n°1 laerts (cello) founded TrioFenix to bring to a wider public Asia. As first violin of the Oxalys Ensemble she plays at the Weiner Trio opus 6 (1908) through concert performance the seldom-played repertoire most prestigious international venues. She is professor at the Dohnanyi Serenade, op. 10 for string trio. As well as the great masterpieces, TrioFenix Conservatoire Royale de Musique de Bruxelles. explore and perform lesser-known and contemporary works written in this genre. From the start, they have had the sup- Tony Nys studied at the Koninklijk Conservatorium Brussel Schubert Allegro D. 471 port of Klara, the Flanders Festival, the Ostbelgian Festival with Clemens Quatacker and Philippe Hirschhorn. As a violist Cras String Trio (1925) and the Musiques en Ecrins Festival among many others. in the Danel Quartet from 1998 till 2005 he played world- Jongen Trio op. 135 wide in numerous festivals, recordings and performances of Beethoven Trio, op. 9 n°3 Their first CD was recorded in 2010 on the Fuga Libera la- newly composed pieces. Since 2005 he has regularly worked bel. The well-known Divertimento KV 563 and the six Adagio as a freelance musician with ensembles such as Prometheus, and Fugues KV 404a by W.A.Mozart became their musical Ictus, Ensemble Modern, Explorations. He is currently member Bach Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 calling card and a significant step for TrioFenix. -

VON DITTERSDORF Six String Trios VAŇHAL Divertimento in G J.M. HAYDN Divertimento in C

Divertimenti Viennesi VON DITTERSDORF Six String Trios VAŇHAL Divertimento in G J.M. HAYDN Divertimento in C Musica Elegentia Matteo Cicchitti conductor Divertimenti Viennesi “Divertimenti Viennesi” It is the name of a musical genre intended for two, three, four or more solo parts. The Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf 1739-1799 Jan Krˇtitel Vanˇhal 1739-1813 movements in which a Divertimento is articulated are not conceived in polyphonic Six String Trios Divertimento in G style nor are they as elaborate as in the Sonata. They do not have a very accentuated for two Violins and Violone for Violin, Viola and Violone character, as they are sound images that aim to give pleasure in hearing, rather than Trio I 13. Allegro 3’13 expressing a given feeling in all its facets. 1. Allegro 4’30 14. Minuetto 3’04 2. Minuetto 4’36 15. Adagio 4’03 This is how Heinrich Christoph Koch defined the instrumental genre of 16. Minuetto 4’24 “Divertimento” in the Musikalische Lexicon (1802). In fact, Koch’s definition refers Trio II 17. Allegro 2’32 to what we might consider the second season of the divertimento genre, starting 3. Andante 4’59 around 1780. Before this date, in fact, ‘Divertimento’ was an all-encompassing 4. Minuetto 2’15 Johann Michael Haydn 1737-1806 term, and designated all non-orchestral instrumental music, including sonatas and Trio III Divertimento in C quartets (the quartets of Franz J. Haydn, until Op.20, bear the title ‘Divertimento’). 5. Presto 4’22 for Violin, Viola and Violone Only after 1780 this term designated a music in a lighter style compared with the 6. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

Symphony No.1, Op.7: 30 Minutes + (Cpo Cd) 1922-23: Symphony No.2, Op.12: 57 Minutes + (Cpo Cd) 1922: Concerto Grosso No

ERNST KRENEK: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1921: Symphony No.1, op.7: 30 minutes + (cpo cd) 1922-23: Symphony No.2, op.12: 57 minutes + (cpo cd) 1922: Concerto grosso No. 1 for six instruments and string orchestra, op. 10 (withdrawn) Symphony No.3, op.16: 43 minutes + (cpo cd) 1923: Piano Concerto No.1, op.18: 30 minutes Symphonic Music No.2/Divertimento for chamber orchestra, op. 23 (withdrawn) 1924: Concerto grosso for violin, viola, cello and orchestra, op.25: 26 minutes + (cpo cd) Concertino for Flute, Violin, Harpsichord and Strings, op.27: 20 minutes Violin Concerto No.1, op.29: 22 minutes + (Koch cd) Seven Orchestral Pieces, op.31: 20 minutes 1924-25: Symphony for winds and percussion, op.34 1924-26: Three Merry Marches for wind band, op.44: 10 minutes 1925: Ballet “Mammon”, op.37: 40 minutes Ballet “Der vertauschte Cupido”, op.38 1926: Suite “Triumph der Empfindsamkeit” for soprano and orchestra, op.43a: 17 minutes 1927/54: “Potpourri” for orchestra, op.54: 16 minutes + (cpo cd) 1928: “Monolog der Stella” for soprano and orchestra, op.57a: 10 minutes Little Symphony, op.58: 15 minutes 1929/73: “Travel Book from the Austrian Alps” for voice and orchestra, op. 62b: 75 minutes 1931: “Durch die nacht” for soprano and orchestra, op.67a: 18 minutes “Die Nachtigall” for soprano and chamber orchestra, op. 68a: 8 minutes + (Toccata Classics cd) Theme and Thirteen Variations for orchestra, op.69: 20 minutes Little Music for winds, op.70a: 14 minutes 1936/66: Adagio and Fugue for string orchestra, op.78: 15 minutes + (Capriccio cd) 1937: Overture “Campo marzio” for small orchestra, op. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

The Evolution of Sonata Form in the Wind Music of W.A. Mozart

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digital Commons / Institutional Repository Information Digital Commons - Information and Tools March 2006 The Evolution of Sonata Form in the Wind Music of W.A. Mozart Brian Alber University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ir_information Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Alber, Brian , "The Evolution of Sonata Form in the Wind Music of W.A. Mozart" (2006). Digital Commons / Institutional Repository Information. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ir_information/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Commons - Information and Tools at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Commons / Institutional Repository Information by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is held up as the pinnacle of Classical ideals. The numerous writings on his life and music are extensive and represent a large body of research into one of the most prolific composers to ever live. Embodying all major genres such as the string quartet, the symphony, the solo concerto and opera, Mozart confidently displayed his mastery in all instrumental and vocal combinations. Through his music, we can see a clear development in formal concepts starting with established schemes such as rondo and minuet forms from the Baroque period, to sonata forms that were cemented during the Classical period. A survey of Mozart’s symphonies and concerti clearly demonstrate his development and mastery of sonata form. It is within his wind music that a similar maturation occurs, although on a smaller scale. -

New Look. New Season. Same World-Class Music

New Look. New Season. Same World-Class Music. JOIN US FOR OUR 2017-2018 SEASON! Lexington Symphony is a professional orchestra of cele- brated musicians who share a passion for classical music and understand the power of music to build community. Founded in 1995, Lexington Symphony’s dual mission combines performance of six affordable and accessible world-class concerts in the heart of MetroWest with award- winning educational outreach programs introducing clas- sical music to audiences of all ages and reaching thousands of area youth annually. Named one of the “busiest conductors in the world”* for the second year in a row, Maestro Jonathan McPhee’s tireless focus and penchant for innovative programming entertains and enlightens audiences. A catalyst for Lexington Sympho- ny’s organizational and artistic growth, McPhee has led “The conductor has the pulse of the audience orchestras around the globe. He currently serves as Music and created a remarkable movie music concert Director for Symphony New Hampshire and is the Music geared to all of us—old, young, and in-between. Director Emeritus for Boston Ballet, where he served as Music Director and Principal Conductor for 27 years. The solo instrumentalists were fabulous. The orchestra was terrific. A night to remember.” *bachtrack.com CONDUCTOR’S TALKS Join Maestro Jonathan McPhee for SEPTEMBER 23, 2017 | SATURDAY, 8PM his Conductor’s Talk, an up-close Musical Mosaics and informal discussion prior to Glass | Concerto Grosso each regular season program**. Elgar | Cello Concerto Mr. McPhee brings classical Nathaniel Taylor, Soloist Schumann | Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish) music to life with relatable insights into composers, com- In the season’s opening concert, we explore the mosaics of music and feature positions, and classical music in Nathaniel Taylor, 2017 Boston Conservatory Concerto Competition Winner, general. -

Program Otes

Object 1 PROGRAM OTES Béla Bartók – Divertimento for String Orchestra Béla Bartók Born March 25, 1881, Nagyszentmiklós, Transylvania (now part of Romania). Died September 26, 1945, New York City. Composition History Bartók composed this work in Saanen, Switzerland, between August 2 and 17, 1939; the first performance was given on June 11, 1940, by the Basle Chamber Orchestra (for which it was written) under the direction of Paul Sacher. The score calls for a minimum of six first and six second violins, four violas, four cellos, and two basses. Performance time is approximately twenty-seven minutes. Performance History The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bartók’s Divertimento for String Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 21 and 22, 1957, with Fritz Reiner conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on December 4, 5, and 7, 2003, with Pierre Boulez conducting. Divertimento for String Orchestra After Bartók’s death in 1945, Paul Sacher wrote: “Whoever met Bartók, thinking of the rhythmic strength of his work, was surprised by his slight, delicate figure.” Bartók was sickly from early childhood. By the time he began writing music at the age of nine, he had already suffered a number of ailments, including eczema, pneumonia, and curvature of the spine. When Paul Sacher met him in 1929, the power of Bartók’s music was widely recognized. Sacher would soon add to the composer’s catalog by commissioning two major works for his own Basle Chamber Orchestra. The young Swiss conductor and this delicate giant of twentieth-century music remained close friends till Bartók’s death. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

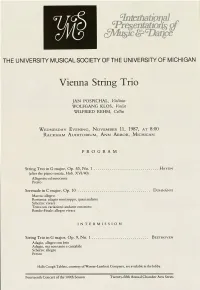

Vienna String Trio

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Vienna String Trio JAN POSPICHAL, Violinist WOLFGANG KLOS, Violist WILFRIED REHM, Cellist WEDNESDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 11, 1987, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM String Trio in G major, Op. 53, No. 1 ................................ HAYDN (after the piano sonata, Hob. XVI/40) Allegretto ed innocente Presto Serenade in C major, Op. 10 .................................... DOHNANYI Marcia: allegro Romanza: adagio non troppo, quasi andante Scherzo: vivace Tema con variazioni: andante con moto Rondo-Finale: allegro vivace INTERMISSION String Trio in G major, Op. 9, No. 1 ............................ BEETHOVEN Adagio, allegro con brio Adagio, ma non tanto e cantabile Scherzo: allegro Presto Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Fourteenth Concert of the 109th Season Twenty-fifth Annual Chamber Arts Series Program Notes Trio in G major, Op. 53, No. 1 ........... FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) The trios of Haydn, Mozart, and Schubert have their origins in the music of the divertimento. Haydn was a leader in the development of the string trio at that time, as in that of the string quartet. About 80 trios by him for various combinations are known, as well as some 126 trios with baryton composed by Haydn for his patron Prince Esterhazy, who loved to play the baryton (an 18th-century bowed stringed instrument similar to the bass viol). The three trios of Opus 53 are identical with the piano sonatas Hob. XVI/40-42, which Haydn wrote in 1784. It is not known which version was original, nor who made the transcription whether Haydn himself or an associated musician.