Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS RELEASE Six Top Law Firms Give

NEWS RELEASE Media Contact: Leslie Hatamiya Executive Director (415) 856-0780 ext. 303 [email protected] Six Top Law Firms Give $180,000 to California Bar Foundation Scholarship Program 2007 Awards Benefit 39 Future Public Interest Lawyers San Francisco – September 24, 2007 – The California Bar Foundation today announced gifts totaling $180,000 from six of California’s top law firms in support of the Foundation’s flagship Law School Scholarship Program. Scholarship awards to outstanding California law students intending to pursue public interest law careers have been named after the six participating firms – Cox, Castle & Nicholson LLP, Dreier, Stein & Kahan LLP, Fulbright & Jaworski L.L.P., Milstein, Adelman & Kreger LLP, Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP, and Seyfarth Shaw LLP – each of which have pledged $30,000 to the Scholarship Program over three years. “Our firm is privileged to participate in the California Bar Foundation's Scholarship Program, which, by supporting future public interest lawyers, helps ensure full and equal access to justice,” said Bradley S. Phillips, a partner at Munger, Tolles & Olson and a member of the Foundation’s Board of Directors. “We are thrilled to invest in impressive law students committed to giving back to their communities. It is an investment in human capital that will benefit the justice system for years to come.” This year, the Foundation is distributing $187,500 in Law School Scholarships to 39 students from 17 California law schools. Recipients, who are nominated by their law schools and demonstrate a commitment to public service, academic excellence, and financial need, receive scholarships of up to $7,500 to assist with tuition and related education expenses. -

PATHWAY to LAW Building a Diversity Pipeline Into the Law

PATHWAY TO LAW Building a Diversity Pipeline into the Law A PARTNERSHIP OF: The State Bar of California The California Lawyers Association The California Department of Education The California Community College Chancellor’s Office’ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School The University of California Undergraduate and Law School @ Davis, Berkeley, UCLA, and Irvine Santa Clara University and School of Law University of San Francisco and School of Law University of Southern California and School of Law Pepperdine University and School of Law State Bar of California 2004 Long Term Strategic Plan Values Statement: The State Bar of California believes in Diversity and Broad Participation in Bar Membership and Leadership. Mission: The State Bar of California's mission is to protect the public and includes the primary functions of licensing, regulation and discipline of attorneys; the advancement of the ethical and competent practice of law; and support of efforts for greater access to, and inclusion in, the legal system. Assembly Bill 3249 Signed by Governor Brown September 2018 The bill requires the State Bar to develop and implement a plan to meet certain goals relating to access, fairness, and diversity in the legal profession and the elimination of bias in the practice of law. The bill would require the State Bar to prepare and submit a report on the plan and its implementation to the Legislature, by March 15, 2019, and every 2 years thereafter. The first Diversity Report to the Legislature was submitted by the State Bar of California in March 2019. COUNCIL ON ACCESS AND FAIRNESS Created in 2007 Think Tank for diversity in the legal profession Supported creation of law academies in 2010 as the first “Boots on the Ground” diversity program Launched the Pathway to Law Initiative in 2014 The California Lawyers Association The California Lawyers Association, formed in 2018, included Diversity and Inclusion in their Mission Statement. -

Loyola Lawyer Law School Publications

Loyola Lawyer Law School Publications Fall 9-1-1990 Loyola Lawyer Loyola Law School - Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/loyola_lawyer Repository Citation Loyola Law School - Los Angeles, "Loyola Lawyer" (1990). Loyola Lawyer. 24. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/loyola_lawyer/24 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola Lawyer by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALUMNI DINNER SET FOR NOVEMBER 15 he Loyola Law School Alumni Friedlander; John]. Karmelich, Charles Dinner honoring distinguished H. Kent, ]ames H. Kindel, Harry V T alumnus Professor William Leppek, Stanley P. Makay. Angus D. Coskran '59 and The Class of 1940 will be McDonald, John R. Morris, Hon. Thomas held Thursday. November 15, 1990 at the c. Murphy. P.E Rau, George R. Stene, Sheraton Grande Hotel in downtown Steven Wixon and Jack E. Woods. Los Angeles. Tickets for the dinner are $75 each or The Distinguished Service Award will $750 for a table of ten. For reservations be presented to Coskran by the Loyola and ticket information, contact the Law School Alumni Association for de Loyola Alumni Office at (213) 736-1096. dicated and humanitarian service to his Cocktails will be served at 6:00p.m., and school, profession and community Past dinner at 7:30p.m., in the Sheraton's recipients ofthe Loyola Law School Grande Ballroom. -

SIG Client List

SIG Client List Since 1987, SIG has completed hundreds of assignments at colleges and universities across the United States and internationally. Engagements have ranged from ERP procurements, implementations, assessments, DBA support, and programming to consulting and training, project management, temporary IT staffing, business process analysis, and IT planning. The following list does not include individual colleges within a client college district. ◼ Abilene Christian University, Texas ◼ Central State University, Ohio ◼ Aims Community College, Colorado ◼ Cerritos College, California ◼ Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University, ◼ Chabot-Las Positas Community College District, Alabama California ◼ Alamo Community College District, Texas ◼ Chaffey College, California ◼ Albany State University, Georgia ◼ Chapman University, California ◼ Albion College, Michigan ◼ Chattanooga State Community College, ◼ Alfred University, New York Tennessee ◼ Allan Hancock Community College District, ◼ Chicago State University, Illinois California ◼ Chippewa Valley Technical College, Wisconsin ◼ Alliant International University, California ◼ Christian Brothers University, Tennessee ◼ American University of Beirut, Lebanon ◼ Christopher Newport University, Virginia ◼ Angelo State University, Texas ◼ Citrus College, California ◼ Antelope Valley College, California ◼ City College of San Francisco, California ◼ Appalachian State University, North Carolina ◼ City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong ◼ Arkansas State University - Jonesboro, Arkansas ◼ Clackamas -

Sande Lynn Buhai

SANDE LYNN BUHAI Loyola Law School 213 – 736 1156 919 Albany Street [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90041 EDUCATION: Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, CA, J.D. 1982, cum laude (top 6%) Loyola International Law Journal, Note and Comment Editor Loyola Reporter, Staff Western State Scholarship Recipient Mabel Wilson Richards Scholarship Recipient St. Thomas More Law Honor Society Scott Moot Court Kings College of Law, University of London, UK, Summer 1981 University of California at Los Angeles, CA, B.A., English 1979 Daily Bruin, Staff PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, CA Clinical Professor, 1994-present Visiting Professor, 1989-1994 Director, Public Interest Law Department, 1994-present Coordinator, Appellate Advocacy Program, 2000-2016 Chair, Admissions Committee, 2013-15 Member, Admissions Committee, Clinics and Externships Committee, Advocacy Committee Courses taught: Ethical Lawyering, Administrative Law, Trial Advocacy, Appellate Advocacy, Disability Rights, Legal Drafting, Law Practice Management, Public Interest Seminar, Animal Law, Introduction to Negotiation, Torts, and Legal Writing Southwestern University School of Law, Los Angeles, CA Visiting Professor, Sum 2005, 2006, 2007, Fall 2007, Sum 2008, Fall 2010 Courses taught: Disability Law, Animal Law University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China Visiting Professor, Sum 1991 Course taught: U.S. Corporations 2019 – Sande Buhai CV Page 1 Western Law Center for Disability Rights, Los Angeles, CA Executive Director, 1989-1994 Responsible for managing the organization, supervising staff and students, and serving as lead attorney on complex disability rights litigation. Increased staff and budget by 100% over five years. Deputy Attorney General, State of California, 1984-1989 Represented the California Department of Consumer Affairs in civil and administrative actions. -

Brenda M. Simon

BRENDA M. SIMON Associate Professor, Thomas Jefferson School of Law Non-Resident Fellow, Stanford Law School Edison Innovation Fellow, George Mason University 1155 Island Avenue, San Diego, CA 92101 • (619) 961-4307 • [email protected] http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/cf_dev/AbsByAuth.cfm?per_id=1022067 EDUCATION University of California, Berkeley, School of Law (Boalt Hall) J.D., 2000, with Intellectual Property Law Specialization Prosser Award in Intellectual Property Executive Editor, Berkeley Technology Law Journal Chair, Moot Court Board University of California, Los Angeles B.S., 1997, General Chemistry, summa cum laude Phi Beta Kappa President, UCLA Mortar Board, National Community Service Organization Talk Show Host and Disc Jockey, KLA Radio FELLOWSHIPS AND CLERKSHIP Stanford Law School, Stanford, CA Non-Resident Fellow, Center for Law and the Biosciences, July 2010-present Teaching Fellow, Law, Science and Technology LLM program, May 2008-July 2010 Fellow, Center for Law and the Biosciences, May 2008-July 2010 Researched intellectual property, technology, and biosciences related issues. Designed and taught Law, Science and Technology course, both semesters. Participated in faculty and fellow workshops. Responsible for all aspects of the Law, Science and Technology LLM program, including teaching, grading, student advising, and admissions. Coordinated Center for Law and Biosciences Speaker Series, conferences, and journal clubs. Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA Fellow, 2017-2018 Research intellectual property and technology related issues; participate in workshops. Draft paper describing research findings; review and comment on other fellows’ projects. Interact with industry leaders and innovators. U.S. District Court, Central District of California, Los Angeles, CA Law Clerk to the Honorable Mariana R. -

2007-2009 College Catalog

WWHITTIERWHITTIER CCOLLEGEOLLEGE 2007-2009 ISSUE OF THE WHITTIER COLLEGE CATALOG Volume 89 • Spring 2007 Published by Whittier College, Offi ce of the Registrar 13406 E. Philadelphia Street, P.O. Box 634, Whittier, CA 90608 • (562) 907-4200 • www.whittier.edu Accreditation Whittier College is regionally accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges. You may contact WASC at: 985 Atlantic Avenue, SUITE 100 Alameda, CA 94501 (510) 748-9001 The Department of Education of the State of California has granted the College the right to recommend candidates for teaching credentials. The College’s programs are on the approved list of the American Chemical Society, the Council on Social Work Education, and the American Association of University Women. Notice of Nondiscrimination Whittier College admits students of any race, color, national or ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, marital status, sexual orientation, national or ethnic origin in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, or athletic and other school-administered programs. Whittier College does not discriminate on the basis of disability in admission or access to its programs. Fees, tuition, programs, courses, course content, instructors, and regulations are subject to change without notice. 2 TTABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW ..................................................................................Inside -

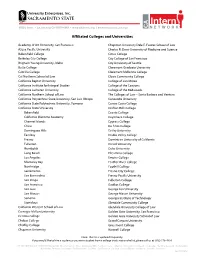

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

Introduction

Introduction I. Structure and Context for the Capacity and Preparatory Review: Whittier College is a small private liberal arts institution, founded in 1887 by members of the Society of Friends. Though the college no longer has any formal association with that society, our identity today is tied closely with our history. Quaker values deriving from that association still influence our ideals and practices. Located on a 75 acre campus seventeen miles east of downtown Los Angeles, Whittier’s primary mission is undergraduate education, but we also offer graduate programs in education. Additionally, like a select group of liberal arts colleges, Whittier has a law school. In 1975, Whittier Law School became part of Whittier College and it is now – with a beautiful stand-alone campus in Costa Mesa - the oldest Law School fully-accredited by the American Bar Association and the Association of American Law Schools in Orange County, California. It offers a full-time day program, a part-time day program, and a part-time evening program leading to the Doctor of Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree. Foreign law students may also earn an LL.M. in U.S. Legal Studies. The School’s strengths include Business Law, Criminal Law, Public Interest Law, Trial and Appellate Law, and the burgeoning fields of Intellectual Property Law, International Law, and Children's Rights. Whittier College’s 2009 Institutional Proposal describes the academic and social principles upon which the college was founded, and the ways that our Mission Statement provides a framework for defining the academic, co- curricular, and administrative elements of the College. -

Q&A with Baylor Law Judges

SPRING ‘15 SCHOOL OF LAW One Bear Place #97288 Waco, TX 76798-7288 Baylor Law is committed to being one of the smallest law schools in the nation. With a total Established in 1857, student body of 383 (fall 2014), we are able to Baylor Law School offer more personalized attention to each student. is ranked third TOTAL PROFILE OF in the nation for STUDENT BODY ENTERING CLASS advocacy by U.S.News FALL 2014 FALL 2014 & World Report. TOTAL ENTERING STUDENTS STUDENTS Every year, Baylor Law 383 83 students achieve one of 58% 42% 75th/25th the highest bar passage MEN WOMEN GPA - 3.71/3.38 (Median 3.55) rates in the country and 75th/25th enjoy an excellent career LSAT - 163/158 placement rate. (Median 160) WITH Q&A WITH BAYLOR LAW JUDGES + BAYLOR LAW JUDGES ACROSS THE NATION VOLUME 127 | SPRING ‘15 BAYLOR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW MAGAZINE 4 Dean’s Letter 16 Alumni Notes 18 Student Notes 21 Commencement Photos 22 Faculty Notes 23 Adjunct Faculty Profiles 26 Obituaries 28 Out & Abouts 30 Back in Time © Baylor University School of Law. All Rights Reserved. VOLUME 127 | SPRING ‘15 BAYLOR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW MAGAZINE 4 Dean’s Letter 16 Alumni Notes 18 Student Notes 21 Commencement Photos 22 Faculty Notes 23 Adjunct Faculty Profiles 26 Obituaries 28 Out & Abouts 30 Back in Time © Baylor University School of Law. All Rights Reserved. A Message Docket Call is published by the Baylor University from Dean Toben School of Law for its alumni, faculty, staff, students, supporters, and friends. -

Applicants to Accredited Law Schools

Applicants to Accredited Law Schools, 2012-2013 WFU National Seniors All Seniors All Number of Applicants 47 107 19,576 59,384 Average LSAT Score 156.4 157.9 153.8 153.1 Percentile 67th 71st 56th 56th Undergraduate GPA 3.34 3.22 3.37 3.26 Admitted to ABA Law School(s) Number 42 94 16,769 45,700 Percent 89% 88% 86% 77% Enrolled at a Law School Number 36 83 14,672 37,936 Percent 77% 78% 75% 64% Admissions per Applicant 3.85 3.58 3.48 2.82 Law Schools Admitting Wake Forest Applicants, 2012-2013 An asterisk (*) indicates that a student from Wake Forest enrolled at the school. Albany Law School of Union University* Michigan State University College of Law University of Chicago Law School American University Washington College of Law* Mississippi College of Law University of Cincinnati College of Law Appalachian School of Law New England Law – Boston University of Connecticut School of Law* Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School* New York Law School University of Denver School of Law Baylor University School of Law New York University School of Law University of the District of Columbia Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law* North Carolina Central University* University of Florida* Boston College Law School Northeastern University School of Law University of Georgia School of Law Boston University School of Law* Northern Kentucky University University of Houston Law Center Brooklyn Law School* Northwestern University School of Law University of Idaho School of Law* Campbell University* Notre Dame Law School University of Illinois College of Law Charleston -

LMU at a Glance 2020-21

LMU at a Glance 2020-21 Student Life Enrollment LMU in L.A. Academics LMU offers60 major and 56 minor Undergraduate 6,564 LMU generates more than $1 billion Loyola Marymount University is undergraduate degrees and programs. The Graduate 1,869 annually for the U.S. economy, with a direct designated a National University/High Graduate Division offers49 master’s degree Law School 1,144 economic impact of more than $850 million Research Activity (R2) by the Carnegie programs, one education doctorate, one juris Total 9,577 in California and more than 5,400 jobs Classifications. This description reflects doctorate, one doctorate of juridical science in California. LMU’s teacher-scholar model; the national and 14 credential/authorization programs. Undergraduate tuition and fees: $52,577 reputation of our Doctorate in Educational (2020-21) Employs more than 2,000 faculty and staff. Leadership program; Loyola Law School’s 20 student housing facilities for Graduate tuition: $1,100-$1,733 Students volunteer nearly 200,000 innovative Doctor of Juridical Science 3,684 students (2020-21, per unit/by program) service hours a year with 250 community program; and the strength of our scholarly Average room and board: $15,550 organizations. productivity and institutional commitment 20 Division I and varsity sports Member (2020-21) to research. LMU shelters a Phi Beta Kappa of West Coast Conference Loyola Law School was the first ABA- chapter and an Alpha Sigma Nu chapter. Average undergraduate class size: 19 accredited law school in California with 202 registered student organizations Average graduate class size: 14 a mandatory pro bono requirement, and Colleges and Schools 26 Inter/National Greek fraternities Student-to-faculty ratio: 10:1 students completed 40,000 hours of pro LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts and sororities bono work.