Volume 39 2012 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10000 Meters

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s 10000m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Kenyan woman never won the W10000m in the OG. Will H Obiri be the first? 2) Showdown between Hassan & Gidey. Can Hassan become first from NED to win the Olympic 10000m? 3) Can Tsehay Gemechu become second (after Tulu) All African Games champion to win the Olympics. 4) Can Gezahegne win first medal for BRN? 5) Can Eilish McColgan become second GBR runner (after Liz, her mother) to win an Olympic medal? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 29:17.45 Almaz Ayana ETH 1 Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 2 29:32.53 Vivian Cheruiyot KEN 2 Rio de Jane iro 2016 3 3 29:42.56 Tirunesh Dibaba ETH 3 Rio de Janeiro 2016 4 4 29:53.51 Al ice Aprot Nawowuna KEN 4 Rio de Janeiro 2016 5 29:54.66 Tirunesh Dibaba ETH 1 Beijing 2008 6 5 30:07.78 Betsy Sa ina KE N 5 Rio de Jane iro 2016 7 6 30 :13.17 Molly Huddle USA 6 Rio de Jan eiro 2016 8 7 30:17.49 Derartu Tulu ETH 1 Sydney 2000 Slowest winning time: 31:06.02 by Derartu Tulu (ETH) in 1992 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 15.08 29:17.45 Alm az Ayana ETH Rio de Janeiro 2016 5.73 31:06.02 Derartu Tulu ETH Barcelona 1992 Min 0.62 30:24.36 Xing Huina CHN Athinai 2004 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 29:17.45 Almaz Ayana ETH Rio de Janeiro 2016 29:54.66 Ti runesh Dibaba ETH Beijing 2008 2 29:32.53 Vivian Cheruiyot KEN Rio de Janeiro 2016 30:22.22 Shalane Flanagan USA Beijing 2008 -

10000 Meters

World Rankings — Women’s 10,000 © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN 1956–1980 2-time No. 1 Almaz Ayana broke (rankings not done) an unbreakable WR in Rio. 1981 1982 1 ............Yelena Sipatova (Soviet Union) 1 ...................................Mary Slaney (US) 2 ......... Olga Bondarenko (Soviet Union) 2 .... Anna Domoratskaya (Soviet Union) 3 ............. Yelena Tsukhlo (Soviet Union) 3 .....Raisa Sadreydinova (Soviet Union) 4 ....................Anna Oyun (Soviet Union) 4 ...... Lyudmila Baranova (Soviet Union) 5 ...............Lidia Klyukina (Soviet Union) 5 ...... Svetlana Ulmasova (Soviet Union) 6 ........ Natalya Boborova (Soviet Union) 6 ......... Galina Zakharova (Soviet Union) 7 ............Mariya Danilyuk (Soviet Union) 7 ...... Gabriele Riemann (East Germany) 8 ......... Galina Zakharova (Soviet Union) 8 ........................... Nanae Sasaki (Japan) 9 .... Anna Domoratskaya (Soviet Union) 9 ............................ Kim Schnurpfeil (US) 10 ....................... Akemi Masuda (Japan) 10 ............. Anne-Marie Malone (Canada) © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 10,000 1983 1987 1 .....Raisa Sadreydinova (Soviet Union) 1 ................. Ingrid Kristiansen (Norway) 2 ...... Lyudmila Baranova (Soviet Union) 2 .........Yelena Zhupiyeva (Soviet Union) 3 ......... Olga Bondarenko (Soviet Union) 3 ...........Kathrin Wessel (East Germany) 4 ...................... Aurora Cunha (Portugal) 4 ......... Olga Bondarenko (Soviet Union) 5 ......... Charlotte Teske (West Germany) 5 ................Liz McColgan (Great -

Men's 200M Final 04.09.2020

Men's 200m Final 04.09.2020 Start list 200m Time: 20:42 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Marcus LAWLER IRL 20.30 20.40 20.95 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 20.08.09 2 Jiří POLÁK CZE 20.46 20.63 20.63 AR 19.72 Pietro MENNEA ITA Ciudad de México 12.09.79 3 Kojo MUSAH DEN 20.52 20.67 20.67 NR 20.19 Patrick STEVENS BEL Roma 05.06.96 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Ján VOLKO SVK 20.24 20.24 20.74 MR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM 16.09.11 5 Jonathan BORLÉE BEL 20.19 20.31 21.18 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Boudewijnstadion, Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Eseosa Fostine DESALU ITA 19.72 20.13 20.35 SB 19.76 Noah LYLES USA Stade Louis II, Monaco 14.08.20 7 Richard KILTY GBR 19.94 20.34 20.99 8 Julien WATRIN BEL 20.19 20.80 21.00 2020 World Outdoor list 19.76 +0.7 Noah LYLES USA Stade Louis II, Monaco (MON) 14.08.20 19.80 +1.0 Kenneth BEDNAREK USA Montverde, FL (USA) 10.08.20 Medal Winners Bruxelles previous 19.96 +1.0 Steven GARDINER BAH Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 20.22 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics Winners 20.23 +0.1 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria (RSA) 13.03.20 1. Noah LYLES (USA) 19.83 19 Noah LYLES (USA) 19.74 20.24 +0.8 André DE GRASSE CAN Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2. -

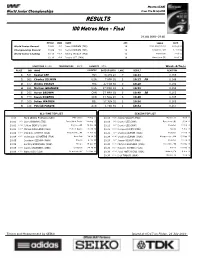

RESULTS 100 Metres Men - Final

Moncton (CAN) World Junior Championships From 19 to 25 July 2010 RESULTS 100 Metres Men - Final 21 JUL 2010 - 21:45 RESULT WIND NAME AGE VENUE DATE World Junior Record 10.01 0.0 Darrel BROWN (TRI) 19 Paris Saint-Denis 24 Aug 03 Championship Record 10.09 -0.6 Darrel BROWN (TRI) 18 Kingston, JAM 17 Jul 02 World Junior Leading 10.16 +0.8 Jimmy VICAUT (FRA) 18 Mannheim 3 Jul 10 10.16 -0.9 Dexter LEE (JAM) 19 Barcelona (O) 9 Jul 10 START TIME 21:48 TEMPERATURE 22°C HUMIDITY 87% Wind: -0.7m/s PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE OF BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION 1 531 Dexter LEE JAM 18 JAN 91 7 10.21 0.166 2 902 Charles SILMON USA 7 APR 91 5 10.23 PB 0.146 3 377 Jimmy VICAUT FRA 27 FEB 92 3 10.28 0.192 4 881 Michael GRANGER USA 17 MAR 91 4 10.32 0.154 5 206 Aaron BROWN CAN 27 MAY 92 6 10.48 SB 0.165 6 774 Jason ROGERS SKN 31 AUG 91 8 10.49 0.185 7 166 Julien WATRIN BEL 27 JUN 92 2 10.56 0.165 8 124 Patrick FAKIYE AUS 1 FEB 91 1 10.62 0.157 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST 9.97 Mark LEWIS-FRANCIS (GBR) Edmonton 4 Aug 01 10.16 +0.8 Jimmy VICAUT (FRA) Mannheim 3 Jul 10 10.01 0.0 Darrel BROWN (TRI) Paris Saint-Denis 24 Aug 03 10.16 -0.9 Dexter LEE (JAM) Barcelona (O) 9 Jul 10 10.01 +1.6 Jeffery DEMPS (USA) Eugene, OR 28 Jun 08 10.21 -0.7 Dexter LEE (JAM) Moncton 21 Jul 10 10.03 +0.7 Marcus ROWLAND (USA) Port-of-Spain 31 Jul 09 10.23 +2.0 Kukyoung KIM (KOR) Daegu 7 Jun 10 10.04 +1.7 D'Angelo CHERRY (USA) Fayetteville, AR 10 Jun 09 10.23 -0.7 Charles SILMON (USA) Moncton 21 Jul 10 10.04 +0.2 Christophe LEMAÎTRE (FRA) Novi Sad 24 Jul 09 10.24 +1.4 Charles SILMON -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

CRBR-Press-Book-2017.Pdf

2017 Elite Runner Highlights 2 Olympians o Shadrack Kipchirchir – represented the U.S.A. at the 2016 Olympics in the 10k o Jen Rhines – represented the U.S.A. at the 2000, 2004, and 2008 Games in the 10k, marathon, and 5k Two-time (2015 & 2016) defending men’s champion – Dominic Ondoro Defending women’s champion – Monicah Ngige 2014 men’s champion – Birhan Nebebew 2011 New York City Marathon Women’s Champion – Firehiwot Dado Male Overall Bib #1 Dominic Ondoro Kenya, 29 Dominic is the two-time defending CRBR Champion (2015 & 2016). He recently conquered the 2017 Houston Marathon, finishing as the champion with a time of 2:12:05. He also won the 2016 Twin Cities Marathon and 2014 Grandma’s Marathon. He clocks a 10k personal best of 28:13, 10 mile personal best of 47:05, and half marathon personal best of 1:01:45. Bib #3 Shadrack Kipchirchir Colorado Springs, CO, 28 Shadrack is a Kenyan-born American distance runner who represented the U.S. at the 2016 nd Olympics in the 10k. He placed 2 at the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials in the 10k, which earned him a spot on Team USA for the Olympics. He is a graduate of Oklahoma State University and enlisted in the US Army in October of 2015 before joining the U.S. Army World Class Athlete Program. Bib #4 Birhan Nebebew Ethiopia, 22 Birhan was the champion of the 2014 CRBR. In 2014, he also won the Hy-Vee Road Races 10k. A year later, he became the runner-up at the 2015 SPAR Great Ireland Run 10k. -

Doha 2018: Compact Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 04.05.2018 Start list 200m Time: 20:36 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Rasheed DWYER JAM 19.19 19.80 20.34 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 20.08.09 2 Omar MCLEOD JAM 19.19 20.49 20.49 AR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 NR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 3 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE GBR 19.94 19.95 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Andre DE GRASSE CAN 19.80 19.80 MR 19.85 Ameer WEBB USA 06.05.16 5 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.88 19.88 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 19.77 19.97 20.12 SB 19.69 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 7 Noah LYLES USA 19.32 19.90 8 Aaron BROWN CAN 19.80 20.00 20.18 2018 World Outdoor list 19.69 -0.5 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 19.75 +0.3 Steven GARDINER BAH Coral Gables, FL 07.04.18 Medal Winners Doha previous Winners 20.00 +1.9 Ncincihli TITI RSA Columbia 21.04.18 20.01 +1.9 Luxolo ADAMS RSA Paarl 22.03.18 16 Ameer WEBB (USA) 19.85 2017 - London IAAF World Ch. in 20.06 -1.4 Michael NORMAN USA Tempe, AZ 07.04.18 14 Nickel ASHMEADE (JAM) 20.13 Athletics 20.07 +1.9 Anaso JOBODWANA RSA Paarl 22.03.18 12 Walter DIX (USA) 20.02 20.10 +1.0 Isaac MAKWALA BOT Gaborone 29.04.18 1. -

Brussels 2020: Full Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 200m Final 04.09.2020 Start list 200m Time: 20:42 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Marcus LAWLER IRL 20.30 20.40 20.95 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 20.08.09 2 Jiří POLÁK CZE 20.46 20.63 20.63 AR 19.72 Pietro MENNEA ITA Ciudad de México 12.09.79 3 Kojo MUSAH DEN 20.52 20.67 20.67 NR 20.19 Patrick STEVENS BEL Roma 05.06.96 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Ján VOLKO SVK 20.24 20.24 20.74 MR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM 16.09.11 5 Jonathan BORLÉE BEL 20.19 20.31 21.18 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Boudewijnstadion, Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Eseosa Fostine DESALU ITA 19.72 20.13 20.35 SB 19.76 Noah LYLES USA Stade Louis II, Monaco 14.08.20 7 Richard KILTY GBR 19.94 20.34 20.99 8 Julien WATRIN BEL 20.19 20.80 21.00 2020 World Outdoor list 19.76 +0.7 Noah LYLES USA Stade Louis II, Monaco (MON) 14.08.20 19.80 +1.0 Kenneth BEDNAREK USA Montverde, FL (USA) 10.08.20 Medal Winners Bruxelles previous 19.96 +1.0 Steven GARDINER BAH Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 20.22 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics Winners 20.23 +0.1 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria (RSA) 13.03.20 1. Noah LYLES (USA) 19.83 19 Noah LYLES (USA) 19.74 20.24 +0.8 André DE GRASSE CAN Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2. -

2009 New York Marathon Statistical Information Men New York Marathon All Time List

2009 New York Marathon Statistical Information Men New York Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:07:43 1 Tesfaye Jifar ETH 1 4 Nov 2001 2 2:08:01 2 Juma Ikangaa TAN 1 5 Nov 1989 3 2:08:07 3 Rodger Rop KEN 1 3 Nov 2002 4 2:08:12 4 John Kagwe KEN 1 2 Nov 1997 5 2:08:17 5 Christopher Cheboiboch KEN 2 3 Nov 2002 6 2:08:20 6 Steve Jones GBR 1 6 Nov 1988 7 2:08:39 7 Laban Kipkemboi KEN 3 3 Nov 2002 8 2:08:43 8 Marilson Gomes dos Santos BRA 1 2 Nov 2008 9 2:08:45 John Kagwe 1 1 Nov 1998 10 2:08:48 9 Joseph Chebet KEN 2 1 Nov 1998 11 2:08:51 10 Zebedayo Bayo TAN 3 1 Nov 1998 12 2:08:53 11 Mohamed Ouaadi FRA 4 3 Nov 2002 13 2:08:59 12 Rod Dixon NZL 1 23 Oct 1983 14 2:09:04 13 Martin Lel KEN 1 5 Nov 2007 15 2:09:07 14 Abderrahim Goumri MAR 2 2 Nov 2008 16 2:09:08 15 Geoff Smith GBR 2 23 Oct 1983 17 2:09:12 16 Stefano Baldini ITA 5 3 Nov 2002 18 2:09:14 Joseph Chebet 1 7 Nov 1999 19 2:09:16 Abderrahim Goumri 2 4 Nov 2007 20 2:09:19 17 Japhet Kosgei KEN 2 4 Nov 2001 21 2:09:20 18 Domingos Castro POR 2 7 Nov 1999 22 2:09:27 Joseph Chebet 2 2 Nov 1997 23 2:09:28 19 Salvador Garcia MEX 1 3 Nov 1991 24 2:09:28 20 Hendrick Ramaala RSA 1 7 Nov 2004 25 2:09:29 21 Alberto Salazar USA 1 24 Oct 1982 26 2:09:29 22 Willie Mtolo RSA 1 1 Nov 1992 27 2:09:30 23 Paul Tergat KEN 1 6 Nov 2005 28 2:09:31 Stefano Baldini 3 2 Nov 1997 29 2:09:31 Hendrick Ramaala 2 6 Nov 2005 30 2:09:32 24 Shem Kororia KEN 3 7 Nov 1999 31 2:09:33 25 Rodolfo Gomez MEX 2 24 Oct 1982 32 2:09:36 26 Giacomo Leone ITA 4 7 Nov 1999 33 2:09:38 27 Ken Martin -

Men's 200M Diamond Discipline 03.05.2019

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 03.05.2019 Start list 200m Time: 19:56 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Owaab BARROW QAT 19.97 21.87 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 20.08.09 2 Leon REID IRL 20.27 21.04 AR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 3 Jaber Hilal AL MAMARI QAT 19.97 21.74 21.90 NR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Alex QUIÑÓNEZ ECU 19.93 19.93 20.28 MR 19.83 Noah LYLES USA 04.05.18 5 Aaron BROWN CAN 19.80 19.98 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.76 19.76 SB 19.76 Divine ODUDURU NGR Waco, TX 20.04.19 7 Alonso EDWARD PAN 19.81 19.81 8 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE GBR 19.94 19.95 9 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 19.77 19.97 20.45 2019 World Outdoor list 19.76 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Waco, TX 20.04.19 20.04 +1.4 Steven GARDINER BAH Coral Gables, FL 13.04.19 20.08 +0.9 Bernardo BALOYES COL Bragança Paulista 28.04.19 Medal Winners Doha previous Winners 20.16 +1.0 Miguel FRANCIS GBR St. George's 13.04.19 20.20 +1.0 Andre DE GRASSE CAN St. George's 13.04.19 2019 - Doha Asian Ch. 18 Noah LYLES (USA) 19.83 20.20 +2.0 Nick GRAY USA Columbia, SC 13.04.19 16 Ameer WEBB (USA) 19.85 20.21 +0.9 Gabriel CONSTANTINO BRA Bragança Paulista 28.04.19 1. -

World Championships Statistics - Women’S 5000M

World Championships Statistics - Women’s 5000m All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 14:38.59 Tirunesh Dibaba ETH 1 Helsinki 2005 2 2 14:39.54 Meseret Defar ETH 2 Helsinki 2005 3 3 14:41.82 Gabriela Szabo ROU 1 Sevilla 1999 4 4 14:42.47 Ejegayehu Dibaba ETH 3 Helsinki 2005 5 5 14:43.15 Zahra Ouaziz MAR 2 Sevilla 1999 6 6 14:43.47 Meselech Melkamu ETH 4 Helsinki 2005 7 7 14:43.64 Xing Huina CHN 5 Helsinki 2005 8 8 14:43.87 Zakia Mrisho TAN 6 Helsinki 2005 9 9 14:44.00 Priscah Jepleting KEN 7 Helsinki 2005 10 10 14:44.22 Ayelech Worku ETH 3 Sevilla 1999 11 11 14:45.14 Isabella Ochichi KEN 8 Helsinki 2005 12 12 14:45.35 Edith Masai KEN 1h1 Paris 2003 13 14:45.96 Tirunesh Dibaba 2h1 Paris 2003 14 13 14:46.47 Sonia O’Sullivan IRL 1 Göteborg 1995 15 14 14:46.73 Sun Yingjie CHN 3h1 Paris 2003 16 15 14:47.07 Liliya Shobkhova RUS 9 Helsinki 2005 17 16 14:47.75 Olga Kravtsova BLR 10 Helsinki 2005 18 17 14:48.33 Marta Dominguez ESP 4h1 Paris 2003 19 18 14:48.54 Fernanda Ribeiro POR 2 Göteborg 1995 20 19 14:50.17 Irina Mikitenko GER 4 Sevilla 1999 21 14:50.98 Tirunesh Dibaba 1h1 Helsinki 2005 22 14:51.19 Sun Yingjie 11 Helsinki 2005 23 14:51.49 Meselech Melkamu 2h1 Helsinki 2005 24 20 14:51.69 Ebru Kavaklioglu TUR 5 Sevilla 1999 25 14:51.72 Tirunesh Dibaba 1 Paris 2003 26 14:52.26 Marta Dominguez 2 Paris 2003 27 14:52.30 Edith Masai 3 Paris 2003 28 21 14:52.36 Yelena Zadorozhnaya RUS 4 Paris 2003 29 14:52.66 Zhara Ouaziz 5h1 Paris 2003 30 22 14:53.56 Elvan Abeylegesse TUR 5 Paris