The Effectiveness of Preparatory Tracks in Jewish Day Schools 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evreiskiye Uroki: Resources, Contacts, and Strategies in Jewish Education for Russian-Speaking Jews

Evreiskiye Uroki: Resources, Contacts, and Strategies in Jewish Education for Russian-Speaking Jews October 2003 UJA-Federation Leadership President Secretary Larry Zicklin* Esther Treitel Chair of the Board Executive Committee at Large Morris W. Offit* Froma Benerofe* Roger W. Einiger* Executive Vice President & CEO Matthew J. Maryles* John S. Ruskay Merryl Tisch* Chair, Caring Commission Marc A. Utay* Cheryl Fishbein* Erika Witover* Roy Zuckerberg* Chair Commission on Jewish Identity and Renewal Vice President for Strategic Planning Scott A. Shay* and Organizational Resources Alisa Rubin Kurshan Chair, Commission on the Jewish People Liz Jaffe* Vice President for Agency and External Relations Chair Louise B. Greilsheimer Jewish Communal Network Commission Stephen R. Reiner* Senior Vice President Paul M. Kane General Campaign Chair Jerry W. Levin* Chief Financial Officer Irvin A. Rosenthal Campaign Chairs Philip Altheim Executive Vice Presidents Emeriti Marion Blumenthal* Ernest W. Michel Philip L. Milstein Stephen D. Solender Daniel S. Och Managing Director of the Commission on Jodi J. Schwartz Jewish Identity and Renewal Lynn Tobias* Rabbi Deborah Joselow Treasurer *Executive Committee member Paul J. Konigsberg* EVREISKIYE UROKI: RESOURCES, CONTACTS, AND STRATEGIES IN JEWISH EDUCATION FOR RUSSIAN-SPEAKING JEWS ABBY KNOPP AND NADYA STRIZHEVSKAYA THE COMMISSION ON JEWISH IDENTITY AND RENEWAL UJA-FEDERATION OF NEW YORK 2003 Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 A Brief Survey of Jewish -

Dfw Private Schools Private Schools

DFW PRIVATE SCHOOLS PRIVATE SCHOOLS COLLIN COUNTY All Saints Catholic School 7777 Osage Plaza Parkway, Dallas, TX 75252 214.217.3300 PK-8 Ann & Nate Levine Academy 18011 Hillcrest Road, Dallas, TX 75252 972.248.3032 PK-8 Bethany Christian School 3300 W Parker Road, Plano, TX 75075 972.596.5811 K-12 Bridge Builder Academy 520 Central Pkwy East #101, Plano, TX 75074 972.516.8844 K-12 Canyon Creek Christian Academy 2800 Custer Parkway, Richardson, TX 75080 972.231.4890 PK-12 Castle Montessori of McKinney 6151 Virginia Parkway, McKinney, TX 75070 972.592.1222 PK-3 Celina Christian Academy PO Box 389, Celina, TX 75009 972.382.2930 K-6 Centennial Montessori Academy 7508 W Eldorado Parkway, McKinney, TX 75070 972.548.9000 K-4 Children’s Carden Montessori 8565 Gratitude Tr, Plano, TX 75024 972.334.0980 NS-3 Christian Care Academy PO Box 1267, Anna, TX 75409 214.831.1383 PK-4 Coram Deo Academy of Collin County 2400 State Highway 121, Plano, TX 75025 972.268.9434 K-11 Cornerstone Christian Academy 808 S. College Street, McKinney, TX 75069 214.491.5700 PK-12 Faith Christian Academy 115 Industrial Blvd A, McKinney, TX 75069 972.562.5323 PK-12 Faith Lutheran School 1701 East Park Boulevard, Plano, TX 75074 972.243.7448 PK-12 Frisco Montessori Academy 8890 Meadow Hill Dr, Frisco, TX 75033 972.712.7400 PK-5 Good Shepherd Montessori School 7701 Virginia Pkwy, McKinney, TX 75071 972.547.4767 PK-5 Great Lakes Aademy (Special Ed) 6000 Custer Rd, Bldg 7, Plano, TX 75023 972.517.7498 1-12 Heritage Montessori Academy 120 Heritage Parkway, Plano, TX 75094 972.424.3137 -

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

Jointorah Education Revolution

the JOIN TORAH EDUCATION REVOLUTION Afikei Torah • Ahavas Torah • Ahava V'achva • Aish HaTorah of Cleveland • Aish HaTorah of Denver • Aish HaTorah of Detroit • Aish HaTorah of Jerusalem • Aish HaTorah of Mexico • Aish HaTorah of NY • Aish HaTorah of Philadelphia • Aish HaTorah of St Louis • Aish HaTorah of Thornhill • Ateres Yerushalayim • Atlanta Scholars Kollel • AZ Russian Programs • Bais Yaakov of Boston • Bais Yaakov of LA • Bar Ilan University • Batya Girls / Torah Links • Bay Shore Jewish Center Be'er Miriam • Belmont Synagogue • Beth Din • Beth Jacob • Beth Jacob Congregation • Beth Tfiloh Upper School Library • Bnei Shalom Borehamwood & • Elstree Synagogue • Boston's Jewish Community Day School • Brandywine Hills Minyan • Calabasas Shul • Camp Bnos Agudah • Chabad at the Beaches • Chabad Chabad of Montreal • Chai Center of West Bay • Chaye Congregation Ahavat Israel Chabad Impact of Torah Live Congregation Beth Jacob of Irvine • Congregation Light of Israel Congregation Derech (Ohr Samayach) Organizations that have used Etz Chaim Center for Jewish Studies Hampstead Garden Suburb Synagogue • Torah Live materials Jewish Community Day Jewish FED of Greater Atlanta / Congregation Ariel • Jewish 600 Keneseth Beth King David Linksfield Primary and High schools • King 500 Mabat • Mathilda Marks Kennedy Jewish Primary School • Me’or 400 Menorah Shul • Meor Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya 206 MTA • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • 106 Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • 77 Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 46 Shapell's College • St. John's Wood Synagogue • The 14 Tiferes High Machon Shlomo 1 Me’or HaTorah Meor • Me'or Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya College • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 2011 2014 2016 2010 2015 2013 2012 2008 2009 Shapell's College St. -

Private Schoolprivate Guideschools COMPLIMENTS of CHICAGO TITLE DFW

GREATER DALLAS-FT. WORTH AREA Private SchoolPRIVATE GuideSCHOOLS COMPLIMENTS OF CHICAGO TITLE DFW DFW DFW CHICAGOTITLEDFW.COM Grades Student/ Addison Phone Max Tuition Enrollment Comments Taught Teacher Ratio Greenhill School 1 972-628-5400 $31,675 1,318 PreK-12 18:1 Co-ed 4141 Spring Valley Trinity Christian Academy Co-ed; uniforms; 2 972-931-8325 $20,600 1,530 PreK-12 17001 Addison Christian Grades Student/ Allen Phone Max Tuition Enrollment Comments Taught Teacher Ratio Co-ed; uniforms; 3 Heritage Montessori Academy 972-908-2463 168 PreK-3 18:1 1222 N Alma Montessori Co-ed; uniforms; 4 Montessori School at Starcreek 972-649-5890 14 PreK-6 915 Ridgeview Montessori Grades Student/ Anna Phone Max Tuition Enrollment Comments Taught Teacher Ratio Christian Care Academy 5 214-831-1383 31 PreK-4 6:1 Co-ed; Christian 13202 N Hwy 5 Grades Student/ Argyle Phone Max Tuition Enrollment Comments Taught Teacher Ratio Liberty Christian Academy Co-ed; uniforms; 6 940-294-2000 $18,480 1,300 PreK-12 18:1 1301 S Hwy 377 Christian Grades Student/ Carrollton Phone Max Tuition Enrollment Comments Taught Teacher Ratio Carrollton Christian Academy Co-ed; uniforms; 7 972-242-6688 14,250 200 K-12 2205 E Hebron Christian Castle Hills Montessori Co-ed; uniforms; 8 972-492-5555 290 PreK-3 1416 W Hebron Montessori Co-ed; uniforms; 9 King Arthur Montessori Academy 972-395-0527 42 PreK-2 10:1 4537 N Josey Montessori Oak Crest 10 1200 E Jackson 214-483-5400 $11,700 45 PreK-8 Co-ed Prince of Peace Christian School Co-ed; uniforms; 11 972-447-0532 $15,580 961 PreK-12 4004 Midway Christian St. -

2,500+ Maimonides Jewish Day School, Portland, OR Students Represented Bnot Yaakov Kol Yaakov Schools, Great Neck, NY Pre-School – High School Torah Prep School of St

LEADERSHIP: JULIS PRINCIPAL TRAINING INSTITUTE (PTI) GOALS · to train the next generation of school leaders in a comprehensive program led by experienced school administrators · to provide ongoing coaching and mentoring to graduates of the Principal Training Institute during their initial years on the job · to provide placement services to schools, including head of school searches and follow-through after placement 2018 PTI BY THE NUMBERS PTI MEMBERS COMPRISE Chaviva High School, Cleveland, OH 25 SCHOOL LEADERS Mazel Day School, Brooklyn, NY FROM AROUND THE COUNTRY: Cincinnati Hebrew Day School, Cincinnati, OH Torah Academy, Brookline, MA Vancouver Hebrew Academy, Vancouver, BC Beren Academy, Houston, TX Las Vegas Jewish High, Las Vegas, NV Maayan Torah Day School, Portland, OR Ganeinu Learning Center, Fresh Meadows, NY Jewish Institute of Queens, Elmhurst, NY Mesivta Yam HaTorah, Far Rockaway, NY Yeshiva Shaarei Zion, Forest Hills, NY Torah Academy for Girls, Far Rockaway, NY Hebrew Academy of Huntington Beach, Huntington Beach, CA Yeshiva of Central Queens, Flushing, NY Esformes Hebrew Academy, Ormond Beach, FL Lubavitch Educational Center, Miami, FL United Lubavitch Yeshivoth, Brooklyn, NY Cheder Chabad of Long Island, Lynnbrook, NY 2,500+ Maimonides Jewish Day School, Portland, OR students represented Bnot Yaakov Kol Yaakov Schools, Great Neck, NY Pre-School – High School Torah Prep School of St. Louis, St. Louis, MO The Julis PTI began its fourth cohort July 2018 with 25 school leaders from around the US and Canada ∙ ∙ ∙ WHAT’S NEW ∙ ∙ ∙ 44 CONSORTIUM OF JEWISH DAY SCHOOLS 51% of survey respondents reported that their expectations were exceeded at the 2018 CoJDS national conference Mentors Mrs. -

Downtown Jewish Chicago” SUNDAY, AUGUST 26 1:00 PM — 3:30 PM Meet in the Chicago Cultural Center Lobby • 78 East Washington Street Guide: Herbert Eiseman

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 36, No. 1, Spring 2012 Errors throughout the print edition corrected chicago jewish historical societ y here, August 29, 2012 chicago jewish history Rae Silverman: West Side Basketball Star ast year , in March, the Society Lreceived a donation of memor- abilia from the collection of the late Rae Silverman Levine Margolis. The collection was mailed to us from Omaha, Nebraska, by Rae’s daughter-in-law, Rayna Levine, the wife of Rae’s son, Daniel. Among the items were cut-out and wood-mounted photographs of Marshall High School basketball stars of the early 1940s—“Whitey” Siegel, Izzy Acker, Morry Kaplan, and Seymour “Chickie” Zomlefer. Rae’s first husband, Nathan “Boscoe” Levine, was a longtime JPI and ABC coach and gym teacher, as well as a gym teacher, coach, and JPI Girls’ Basketball Team (undated, 1920s). athletic director at Marshall. The Standing: far left, Rose Rodkin, manager; far right, Emil Gollubier, coach. photos might have been decorations, Kneeling: far left, Rose Olbur Winston. Seated: second from left, Gertrude Goldfein perhaps from a party in Boscoe’s Edelcup; third, Anna Goldstein; far right, Rae Silverman Levine Margolis. honor. (Boscoe, Lou Weintraub, Spertus Special Collections. Gift of Daniel U. and Rayna F. Levine. Continued on page 20 Mollie Alpiner Netcher Newbury: The Jewish Merchant Princess of State Street Conclusion of the report on “Jewish Merchant Princes of State Street,” the program presented by Herb Eiseman at our open meeting on April 2, 2011. ollie Alpiner was the knit underwear buyer at the Boston Store in 1891 M when she married her boss, Charles Netcher, owner of the store. -

2013-Dallas Summary Highlights.Pdf

www.dallasjewishcommunityscan.org RepoRt to the community presented by thank you to paRticipants The Dallas Jewish Community Scan: Awareness, Perceptions, and Needs Fifty Jewish agencies, congregations, and organizations in our Greater dallas community came together for a joint effort of discovery. Thank you to our many community leaders and participants who over the past year made that possible. the dallas Jewish Community scan drew honest and thoughtful responses from almost 5,000 individuals, representing one of the largest surveys of a major Jewish community in the country! this process was truly about our Jewish Community with emphasis on the word “Jewish”. What are Jews in dallas aware of when it comes to their Jewish options? What perceptions do we have about those options and do we use them? Lastly, what needs do we have, and are they being met by Jewish service providers? Our community’s responses to the scan are shedding light on the answers. Already, each of the participating organizations has received valuable information about their constituencies and where we have challenges and opportunities going forward. • February through March 2013: Fifty community groups were educated and recruited to participate in the scan, indicating their commitment through signed Letters of Understanding. • April into May: the scan was drafted and tested using multiple focus groups, while agency databases were collected and refined resulting in 25,000 valid email addresses and new information appended for agency’s use (e.g., age, income, etc.) • Through May: the scan was marketed through each of the participating agencies, as well as through targeted media, to drive up participation following the May 27 launch. -

Simcha Guide

2 Stores/Restaurants Bakeries Tel Aviv Kosher Bakery: 2944 W. Devon Ave., Chicago ……………………….…773-764-8877 Bookstores Kesher Stam: 2817 W. Touhy Ave., Chicago .................................................................. 773-973-7826 Rosenblum’s World of Judaica: 9153 Gross Point Road., Skokie ............................... 773-262-1700 Candy Trays Lolipop .................................................................................................................................. 773-956-3397 Florists A Gentle Wind: 2744 W. Touhy Ave., Chicago ............................................................. 773-761-1365 Honey’s Bunch .................................................................................................................... 773-338-9166 Food Markets Hungarian Kosher Supermarket: 4020 Oakton St., Skokie ........................................... 847-674-8008 Jewel: 2485 Howard St., Evanston .................................................................................... 847-328-9791 Kol Tuv Kosher Foods: 2938 W. Devon Ave., Chicago ............................................... 773-764-1800 Mariano’s: 3358 W. Touhy Ave., Skokie .......................................................................... 847-763-8801 Romanian Kosher Sausage: 7200 N. Clark St., Chicago ................................................ 773-761-4141 Restaurants The main Chicago Hechsher for restaurants is the CRC. Please call 773-465-3900 with questions. Dunkin Donuts (dairy): 3132 W. Devon, Chicago ........................................................ -

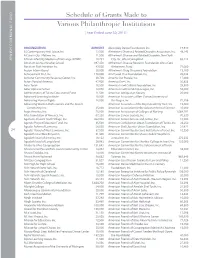

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

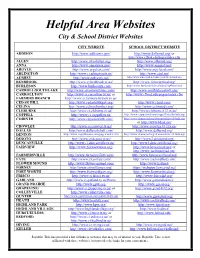

Helpful Area Websites

Helpful Area Websites City & School District Websites CITY WEBSITE SCHOOL DISTRICT WEBSITE ADDISON http://www.addisontx.gov/ http://www.dallasisd.org/ or http://www.cfbisd.edu/pages/index.cfm ALLEN http://www.cityofallen.org/ http://www.allenisd.org/ ANNA http://www.annatexas.gov/ http://www.annaisd.net/ ARGYLE http://www.argyletx.com/ http://www.argyleisd.com/ ARLINGTON http://www.ci.arlington.tx.us/ http://www.aisd.net/ AUBREY http://www.aubreytx.net/ http://www.aubreyisd.net/aubreyisd/site/default.asp BENBROOK http://www.ci.benbrook.tx.us/ http://www.fortworthisd.org/ BURLESON http://www.burlesontx.com/ http://www.burlesonisd.net/home/?q=bisd/bisd CARROLL/SOUTHLAKE http://www.cityofsouthlake.com/ http://www.southlakecarroll.edu/ CARROLLTON/ http://www.ci.carrollton.tx.us/ or http://www.cfbisd.edu/pages/index.cfm FARMERS BRANCH http://www.ci.farmers-branch.tx.us/ CEDAR HILL http://www.cedarhilltxgov.org/ http://www.chisd.com/ CELINA http://www.celinachamber.org/ http://www.celinaisd.com/ CLEBURNE http://www.ci.cleburne.tx.us/ http://www.cleburne.k12.tx.us/ COPPELL http://www.ci.coppell.tx.us/ http://www.coppellisd.com/coppell/site/default.asp CORINTH http://www.cityofcorinth.com/ http://www.dentonisd.org/dentonisd/site/default.asp or http://www.ldisd.net/ CROWLEY http://www.ci.crowley.tx.us/ http://www.crowley.k12.tx.us/ DALLAS http://www.dallascityhall.com/ http://www.dallasisd.org/ DENTON http://www.cityofdenton.com/pages/index.cfm http://www.dentonisd.org/dentonisd/site/default.asp DESOTO http://www.ci.desoto.tx.us/ http://www2.desotoisd.org/