Aug. 2008 Report, Coleman DE 3170/Plata DE 1662

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 29, 2015 Neurocognition in Major

Date Title Speaker Name Degree/ Rank Affiliation October 29, 2015 Neurocognition in Major Psychiatric Katherine Burdick PhD Associate Professor of Psychiatry; Associate Professor of Neuroscience, Icahn Medical Institute, Disorders: A Cross-Diagnostic Dimension Mount Sinai Hospital, New York October 22, 2015 Recent Advances in the Assessment and Terence Keane PhD Professor of Psychiatry and Assistant Dean for Research, Director, Behavioral Science Divison at Treatment of Combat Related PTSD National Center for PTSD, Boston VA HealthCare System October 08, 2015 Sex Therapy, Sexuality and the Aline Zoldbrod PhD AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and Diplomate, Private Practice, Lexington, MA Milestones of Sexual Development: Redefining Sexual Trauma October 01, 2015 Autoimmunity, Inflammation and Erik Istre MD PGY-6 Neuropsychiatry Resident, UMass Medical School/UMass Memorial Healthcare Psychosis September 24, 2015 Medical Treatment of the Transgender Norman Spack MD Co-Director, Gender Management Service, Endocrine Division, Associate Clinical Professor of Adolescent: No Longer Just the Pediatrics, Boston Children's Hospital/Harvard "Caboose" on the LGBT Train Medical School September 17, 2015 Managing Antipsychotic-Associated L. Fredrik Jarskog MD Professor and Research Director, North Carolina Psychiatric Research Center, University of North Weight Gain and Metabolic Deficits Carolina at Chapel Hill September 10, 2015 Transforming Mentorship Through Douglas Ziedonis MD, MPH Professor and Chair, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts -

Jeffrey L. Geller, MD, MPH HOME ADDRESS

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Jeffrey L. Geller, M.D., M.P.H. HOME ADDRESS: BUSINESS ADDRESS: Department of Psychiatry University of Massachusetts Medical School 55 Lake Avenue North Worcester, MA 01655 (508) 856-6527 BIRTH DATE: BIRTH PLACE: New York, NY CITIZENSHIP: U.S.A. EDUCATION AND TRAINING UNDERGRADUATE September 1966- B.A. 1970 June 1970 Psychology Williams College Williamstown, MA January 1969- Exchange Student June 1969 Vassar College Poughkeepsie, NY GRADUATE September 1970- M.D. 1973 December 1973 University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Philadelphia, PA Rotation at the Austen Riggs Center Stockbridge, MA, June, 1971-August, 1971 Rotation at Kaimosi Friends Hospital, Kisumu, Kenya, May, 1973-August, 1973 September 1976- M.P.H. 1978 June 1978 Harvard School of Public Health Boston, MA POST GRADUATE January 1974- Internship June 1974 Philadelphia General Hospital Philadelphia, PA July 1974- Psychiatric Residency June 1977 Beth Israel Hospital Boston, MA July 1977- N.I.M.H. Fellowship June 1978 Psychiatry in Primary Care Medicine Beth Israel Hospital Boston, MA APPOINTMENTS AND POSITIONS ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1974-1978 Fellow Harvard Medical School Boston, MA 1979-1983 Assistant Professor University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester, MA 1982-1984 Clinical Assistant Professor Smith School for Social Work Northampton, MA 1983-1984 Assistant Professor Harvard Medical School Cambridge, MA 1984, 1987, 1989 Adjunct Winter Study Faculty Williams College Williamstown, MA 1984-1986 Assistant Professor University of Pittsburgh, -

Top U.S. Hospitals, 2005

Top U.S. hospitals, 2005 U.S. News & World Report published its annual list of America’s “top” hospitals, featuring 176 hospitals that ranked high enough in at least one of the 17 medical specialties to make the grade. Among them, 16 hospitals earned “Honor Roll” status (shown below in bold type) by achieving top ratings in at least six specialties. Many of these facilities are also on the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s list of Magnet hospitals (shown below in red type), which are recognized for their excellence in nursing service. Only six hospitals turn up on both lists, as shown below in bold red type. State Hospital State Hospital Alabama University of Alabama Hospital at Birmingham Georgia Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Arizona John C. Lincoln Health Network, Phoenix Emory University Hospital, Atlanta Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix St. Joseph’s Hospital of Atlanta St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix Shepherd Center, Atlanta University Medical Center, Tucson Illinois Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge Arkansas Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock Alexian Brothers Medical Center, Elk Grove Village California Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles Centegra Memorial Medical Center, Woodstock Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte Christ Hospital and Medical Center, Oak Lawn Doheny Eye Institute, USC University Hospital, Los Angeles F.G. McGaw Hospital at Loyola University, Maywood Jules Stein Eye Institute, UCLA Medical -

Massachusetts Association of Behavioral Health Systems

Massachusetts Association of Testimony to the Health Policy Commission Behavioral Re: Health Care Cost Growth Benchmark Health Systems Presented by: David Matteodo, Executive Director Massachusetts Association of Behavioral Health Systems 115 Mill Street March 29, 2018 Belmont, MA 02478 Phone: 617-855-3520 On behalf of the Massachusetts Association of Behavioral Health Systems (MABHS), I Michele Gougeon,MSS,MSC appreciate the opportunity to offer this testimony to the Health Policy Commission Chairman regarding the Health Care Cost Growth Benchmark. The MABHS represents 44 inpatient David Matteodo mental health and substance abuse facilities in the Commonwealth, which collectively Executive Director admit over 60,000 patients annually. Our hospitals provide the overwhelming majority of acute inpatient mental health and substance abuse services in the Commonwealth. Members: AdCare Hospital Current Status for Inpatient Behavioral Health: There has been a great deal of activity Arbour Hospital Bournewood Hospital regarding new initiatives in Behavioral Health over the past few years. Including: Fuller Hospital HRI Hospital Beginning in June, 2015 there have been four new freestanding psychiatric hospitals McLean Hospital Southcoast Behavioral Health which opened in Massachusetts. The private sector licensed beds have increased by 419 Steward Health Care System beds during this period, from 2,433 beds to 2,852 (this figure does not include the 671 Pembroke Hospital state hospital beds operated by the Department of Mental Health). Each of these hospitals, Associate Members: located in various parts of the state, are seeking to help address Emergency Department Anna Jaques Hospital Boarding and provide better access to mentally ill and substance use patients. The four Austen Riggs Center new hospitals as well as the expansion of several current facilities, represent Bayridge Hospital Baystate Health System unprecedented developments for inpatient behavioral health in Massachusetts. -

Austen Riggs Implementation Strategy.Pdf

CHNA IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 2019 Assembled by the Austen Riggs Center 25 Main Street 1.800.51.RIGGS Stockbridge, MA 01262 [email protected] June 24, 2019 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 About the Austen Riggs Center ...................................................................... 4 Definition of the Community Served ............................................................... 5 Summary of Significant Community Health Needs ......................................... 6 Implementation Strategy to Address Significant Health Needs ....................... 7 Needs that Austen Riggs Plans to Address Directly ....................................... 8 Needs that Austen Riggs Plans to Address Indirectly ................................... 17 Needs that the Austen Riggs Center Will Not Address ................................. 21 Implementation Strategy Adoption ............................................................... 21 Addendum A - Educational Programs via the Erikson Institute ................. 22 Addendum B – Riggs Staff Grand Rounds Presentations (2016-2018) ...... 28 Austen Riggs Center / CHNA Implementation Strategy 2019 3 Introduction This document describes how the Austen Riggs Center (“Riggs” or “the Center”) plans to address needs found in the Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA). See the CHNA report at www.austenriggs.org/community-health-needs-assessment. The implementation strategy describes how the Center plans to address -

A Patient's Perspective

A Patient’s Perspective The purpose of this folio is to portray a patient’s experience of treatment at the Austen Riggs Center. The work done at Riggs is best illustrated and explained with examples. However, examples must be provided in ways that protect patient confidentiality. Our solution to communicate an authentic patient experience was to create a composite of vignettes, stitched together in one voice. This amalgam of patient stories reflects real and individual experiences culled from interviews with many of our clinicians who work with patients struggling to make or find meaning in their lives. This composite might seem too tidy for some and it is not meant to suggest that life is easy for individuals who complete treatment at Riggs. Nor is this composite meant to be a substitute for aggregate data across the experience of many patients, which can be found on the outcomes section of our website. We hope you read this story to learn about the complexity of treatment at Riggs, the power and value of discovering one’s own voice and take the story as illustrative of a typical Riggs experience. Foreword No one sets out to be a patient in apsychiatric hospital, but some of us endupthere. For me, the Austen Riggs Center was the place that taught me how to acknowledge my troubles and access my strengths in a way that made it possible to move forward with my life. This is the story of my journey to Riggs and through the six months I spent there. It would not have been possible for me to write about any of this while I was at Riggs because it was a very turbulent and, at times, difficult process. -

America's Best Hospitals 2008 Methodology

America’s Best Hospitals 2008 Methodology Emily McFarlane Joe Murphy Murrey G. Olmsted Edward M. Drozd Craig Hill To Whom it May Concern: U.S. News & World Report’s “America’s Best Hospitals” study is the sole and exclusive property of U.S. News & World Report, which owns all rights, including but not limited to copyright, in and to the attached data and material. Any party wishing to cite, reference, publish, or otherwise disclose the information contained herein may do so only with the prior written consent of U.S. News. Any U.S. News-approved reference or citation must identify the source as “U.S. News & World Report’s America’s Best Hospitals” and, with the exception of academic journals, must include the following credit line: “Data reprinted with permission from U.S. News & World Report.” For permission to cite or use in any other way, contact [email protected] or send a written request to Permissions Department, c/o Mary Lu Meixell, U.S. News & World Report, 1050 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW, Washington, DC 20007-3837. For custom reprints, please contact Wright's Reprints at 877.419.5725 or email [email protected]. Table of Contents I. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 A. Index of Hospital Quality........................................................................................... 2 Structure..................................................................................................................... 3 Process -

Ed 042 007 Institution Spons Agency Pub Date Edrs Price

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 042 007 VT 011 028 TITLE Helping All the Handicapped; The Report of the Massachusetts Vocational Rehabilitation Planning Commission. INSTITUTION Medical Foundation, Inc., Boston, Mass. SPONS AGENCY Oregon State Univ., Corvallis, Div. of Vocational, Adult, and Community Coll. Education.; Rehabilitation Services Administration (DREW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 31 Oct 68 NOTE 222p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MP-S1.00 HC-S11.20 DESCRIPTORS Disadvantaged Groups, *Handicapped, Job Placement, *Program Planning, State Federal Aid, *State Programs, *Vocational Rehabilitation IDENTIFIERS Massachusetts ABSTRACT This report by the Planning Commission culminates 2 years of public hearings and the investigations of 10 task forces on vocational rehabilitation. A broader definition of the disabled,one which includes the disadvantaged, is gaining acceptance, resulting in the need for expanded rehabilitation programs. This study provides the necessary guidelines for that expansion. Principal recommendations among the 200 made by the Commission include: (1) administrative reorganization at both state and community level, (2) increased services on a regional level through cooperation of qualified agencies, (3) improved placement efforts, including sheltered employment, (4) extension of the architectural barriers board to cover all buildings open to the public, (5) expanded services for the public offender, (6) adjustment to technological change, (7) strengthened research units, and (8) increased male recruitment and training of personnel. (BH) /IN HELPING ALL THE HANDICAPPED THE REPORT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION PLANNING COMMISSION ,k. *4- ' iR ci6e, 1,7 LOOM003 THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION PLANNING COMMISSION BOSTON, MASS. 02116 His Excellency John A. Volpe October 31, 1968 Governor of the Commonwealth State House Boston, Massachusetts Dear Governor Volpe: On behalf of the members of the Vocational Rehabilitation Planning Commission, appointed in accordance with your Executive Order No. -

Here Are Some Organizations That You Can Turn to for Mental

Aftercare Resource Referral List Here are some Organizations that You can Turn to for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services Emergency services- 911 Advocates Emergency Line- helps families obtain emergency services and psychiatric services (508)872-3333 Samaratis Suicide Hotline (508)875-4500 Massachusetts Substance Abuse Referral Helpline (800) 327-5050 211- Like a 411 for community services and will list all agencies Food and Clothing: your local food pantry, your local church, Good Will Stores, YMCA, Red Cross, Project Bread, Salvation Army, Span Inc For Mental Health Services, Family, and Independent Learning Services: Bamsi,- HIV, counseling, Hep C, Community Based Flexible Support Worker, Housing (508)580-8700 Advocates Inc.- developmental delays, crisis, counseling, in home therapy (508) 628-6300 Riverside Community Care –have special schools, counseling, afterschool programs, mental health respite programs, brain injury program, Substance Abuse, Mental Health Issues, Clubhouse job training (781)329-0909 Aftercare Resource Referral List The Home for Little Wanderers- Foster care, Respite for adolescents, adoption and family support (671)267-3700 Bournewood Health Systems- Substance abuse center, inpatient and ambulatory systems Justice Resource Institute- services for children adult and family, Mental health and substance abuse services. Locations are in Needham or Framingham. (781)559-4900 Edinburg Center-Adult, child and adolescent mental Health issues, Developmental Disabilities, help with employment and Community Based -

October 27, 2016 Risk Management With

Date Title Speaker Name Degree/ Rank Affiliation October 27, 2016 Risk Management With Suicidal Patients: Mark Schechter, MD MD Psychiatry/Psychology, Mass General Hospital/North Shore Medical Center for Helping others while protecting ourselves Outpatient Care October 20, 2016 From Liberia To Lowell: Addressing David C. Henderson MD Psychiatrist in Chief, Division of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine/Boston Medical Unmet Mental Health Needs Center October 13, 2016 The Evidence Base for Family John Sargent MD Chief, Child and Adolescent Psych, Vice Chair Child Adolescent Psych, Professor, Tufts University Interventions in Child and Adolescent School of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Floating Psychiatry Hospital for Children October 06, 2016 Social Motor Coordination as a Means for 1) Paula Fitzpatrick 1) PhD 1) Professor, Chair, Psychology Department, 2) PhD Assumption College Understanding Social Competence in 2) Richard C Schmidt 2) E.A. O'Rourke Professor in Liberal Arts, College Psychological Disorders of the Holy Cross September 29, 2016 Modulation of Cingulate Cortex L. Elliot Hong MD Professor, Director, Neuroimaging Research Program, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, Connectivity: Influence of Nicotine, Dept. of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School Genetics and Schizophrenia of Medicine September 22, 2016 Supported Employment for Persons with Kim T. Meuser PhD Executive Director, Center for Rehabilitation, Boston University Severe Mental Illness: Clinical and Research Update September 08, 2016 Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment Anthony Rothschild MD Irving S and Betty Brudnick Endowed Chair, Professor of Psychiatry, University of of Psychotic Depression Massachusetts Medical School, UMass Memorial Health Care June 16, 2016 Doctors Medicating Badly: Aberrant Steve Adelman MD Clinical Associate Professor, UMass Dept. -

Austen Riggs Admissions Brochure.Pdf

Welcome to the Austen Riggs Center Intensive psychotherapy in an open and voluntary residential setting Treatment Approach THE AUSTEN RIGGS CENTER (Riggs) is widely recognized for a unique Every life treatment approach offering intensive psychotherapy in a completely has meaning. open and voluntary setting. Founded in 1919, Riggs today offers adults with complex psychiatric problems a hospital-based continuum of care that includes inpatient, residential, and day-treatment services. We treat the individual, not the diagnosis. Patients come to us with multiple diagnoses, often including personality and mood disorders; but we understand that these labels do not necessarily capture the essence of their struggles or strengths. We offer intensive psychodynamic psychotherapy within a therapeutic community dedicated to the idea of examined living, in which patients and staff discuss the meanings of behaviors, choices, and interactions with one another in open, collaborative ways. Our work is grounded in the perspective that every life has meaning, every person can be understood within a network of relationships, and treatment leads to a more fulfilling life when the sources of suffering are addressed. We treat Our goal is to help our patients expand their capacity for work, play, and the individual, love by helping them acknowledge and come to terms with psychological not the diagnosis. Our goal is to help and biological impediments to development, and by fostering improved our patients expand self-esteem and resilience. their capacity for Many of our patients have not benefited from other forms of treatment, and work, play, and love. may be described as “treatment resistant” by the wider psychiatric community. -

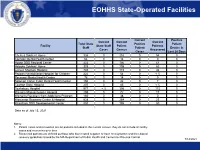

EOHHS Data Dashboard July 14, 2021

EOHHS State-Operated Facilities Current Positive Current Current Current Total State Positive Patient Facility State Staff Patient Patients Staff Patient Deaths in Cases Census Recovered Cases Last 28 Days Chelsea Soldiers' Home 326 0 216 0 54 0 Corrigan Mental Health Center 64 0 14 0 0 0 Hogan DDS Regional Center 422 0 106 0 61 0 Holyoke Soldiers' Home 325 0 105 0 63 0 Lemuel Shattuck Hospital 740 0 172 0 44 0 Pappas Rehabilitation Hospital for Children 222 0 54 0 < 5 0 Pocasset Mental Health Center 78 0 14 0 0 0 Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center 194 0 42 0 7 0 Taunton State Hospital 207 0 45 0 < 5 0 Tewksbury Hospital 977 < 5 306 0 115 0 Western Massachusetts Hospital 295 0 72 0 17 0 Women's Recovery from Addictions Program 160 0 38 0 0 0 Worcester Recovery Center & Hospital 828 0 264 0 25 0 Wrentham DDS Developmental Center 850 0 195 0 80 0 Data as of July 13, 2021 Notes: 1. Patient cases and recoveries are for patients included in the current census, they do not include all facility cases and recoveries over time 2. Recovered patients are defined as those who have tested negative or have met symptom and time-based recovery guidelines issued by the MA Department of Public Health and Centers for Disease Control 7/14/2021 Updated: 7/14/2021 Draft for Discussion Purposes Only 1 EOHHS Congregate Care Sites State-Operated Sites Vendor-Operated Sites Current Current Positive Current Current Current Current Total State Positive Current Positive Client Deaths Agency State Staff Client Clients Clients Staff Client Client Census Client