The Original Giants' Quarterback from Ole Miss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Football Field, in the Booth, Frank Gifford a Winner

8+11+18 PUBLIC NOTICE AND NOTICE OF SPECIAL ROAD DISTRICT ELECTION MARINA PARK ROAD DISTRICT I, Patty Hojem, Yankton Coun- ty Auditor, as provided by SDCL have by August 11, 2015, caused to be posted at 102 Marina Park Drive Yankton, SD, in the pro- posed road district area, the Peti- tion for Organization and Incor- poration of the Marina Park Road District. The area requesting organiza- tion to be effective for the 2016 Tax Year is as follows: Property located in The North 300.00 of the South 633.00 of the East 230.00 of the West 460.00 of the SE1/4 of the NE1/4 of Section 7, Township 93 North, Range 56 West of the 5th P.M., Yankton County, South Dakota, commonly referred to as Lot 10, Marina Park Estates. The North 300.00 of the South 633.00 of the East 196.00 of the West 656.00 of the SE1/4 of the NE1/4 of Section 7, Township 93 North, Range 56 West of the 5th P.M., Yankton County, South Dakota, commonly referred to as Lot 11, Marina Park Estates. The North 300.00 of the South 633.00 of the East 205.00 of the West 861.00 of the SE1/4 of the NE1/4 of Section 7, Township 93 North, Range 56 West of the 5th P.M., Yankton County, South Dakota, commonly referred to as Lot 12, Marina Park Estates. The North 300.00 of the South 333.00 of the East 205.00 of the West 1066.00 of the SE1/4 of the NE1/4 of Section 7, Township 93 North, Range 56 West of the 5th P.M., Yankton County, South Dakota, commonly referred to as Lot 4, Marina Park Estates. -

1-1-17 at Los Angeles.Indd

WEEK 17 GAME RELEASE #AZvsLA Mark Dalton - Vice President, Media Relations Chris Melvin - Director, Media Relations Mike Helm - Manag er, Media Relations Matt Storey - Media Relations Coordinator Morgan Tholen - Media Relations Assistant ARIZONA CARDINALS (6-8-1) VS. LOS ANGELES RAMS (4-11) L.A. Memorial Coliseum | Jan. 1, 2017 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S GAME ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2016 SCHEDULE The Cardinals conclude the 2016 season this week with a trip to Los Ange- Regular Season les to face the Rams at the LA Memorial Coliseum. It will be the Cardinals Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time fi rst road game against the Los Angeles Rams since 1994, when they met in Sep. 11 NEW ENGLAND+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 21-23 Anaheim in the season opener. Sep. 18 TAMPA BAY Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 40-7 Last week, Arizona defeated the Seahawks 34-31 at CenturyLink Field to im- Sep. 25 @ Buff alo New Era Field L, 18-33 prove its record to 6-8-1. The victory marked the Cardinals second straight Oct. 2 LOS ANGELES Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 13-17 win at Sea le and third in the last four years. QB Carson Palmer improved to 3-0 as Arizona’s star ng QB in Sea le. Oct. 6 @ San Francisco# Levi’s Stadium W, 33-21 Oct. 17 NY JETS^ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 28-3 The Cardinals jumped out to a 14-0 lead a er Palmer connected with J.J. Oct. 23 SEATTLE+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium T, 6-6 Nelson on an 80-yard TD pass in the second quarter and they held a 14-3 lead at the half. -

Are You Ready for Some Super-Senior Football?

Oldest living players Are you ready for some super-senior football? Starting East team quarterback Ace Parker (Information was current as of May 2013 when article appeared in Sports Collectors Digest magazine) By George Vrechek Can you imagine a tackle football game featuring the oldest living NFL players with some of the guys in their 90s? Well to tell the truth, I can’t really imagine it either. However that doesn’t stop me from fantasizing about the possibility of a super-senior all-star game featuring players who appeared on football cards. After SCD featured my articles earlier this year about the (remote) possibility of a game involving the oldest living baseball players, you knew it wouldn’t be long before you read about the possibility of a super-senior football game. Old-timers have been coming back to baseball parks for years to make cameo appearances. Walter Johnson pitched against Babe Ruth long after both had retired. My earlier articles proposed the possibility of getting the oldest baseball players (ranging in age from 88 to 101) back for one more game. While not very likely, it is at least conceivable. Getting the oldest old-timers back for a game of tackle football, on the other hand, isn’t very likely. We can probably think about a touch game, but the players would properly insist that touch is not the same game. If the game were played as touch football, the plethora of linemen would have to entertain one another, while the players in the skill positions got to run around and get all the attention, sort of like it is now in the NFL, except the linemen are knocking themselves silly. -

My Emlen Tunnell Story by David Lyons

My Emlen Tunnell Story By David Lyons I grew up listening to stories told by my father, Bill Lyons, about his friend Emlen Tunnell, and we were both always amazed that a biography was never written about him. After considerable reflection and a push from my dad, I decided that I would take that journey and write about our local legend’s life, so that more people would know about his remarkable life story. The American public knows plenty about sports heroes like Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron, but few remember or have even heard of Emlen Tunnell. He is a forgotten star who pioneered his way into the NFL in an uncharacteristic way at the time; he went to the New York Giants office and asked for a tryout. Dozens of books have been written about Jackie Robinson and Vince Lombardi, but none have ever been written about the great Emlen “the Gremlin” Tunnell, who most friends called “Em.” Emlen Tunnell wasn’t merely a legendary football player, he was a highly charismatic real person who was kind to his family and friends. He became a part of my childhood because my dad would share delightful stories around our dinner table with me and my six brothers. Dad was a neighbor and friend of Emlen’s. One of the stories Dad shared with us was how Emlen was moved to tears when a group of homeless guys took up a collection for him when the New York Giants held an Emlen Tunnell Day in 1958. The money collected was less than $30, but Emlen said, “These guys probably gave me all the money they had, and who can ever be more generous than that?” Emlen was a very sensitive and sentimental guy who wore his heart on his sleeve and would tear up rather easily when he felt moved. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

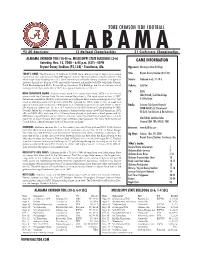

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist 1 Norm Van Brocklin 2 Otto Graham 3 Doak Walker 4 Steve Owen 5 Frankie Albert 6 Laurie Niemi 7 Chuck Hunsinger 8 Ed Modzelewski 9 Joe Spencer 10 Chuck Bednarik 11 Barney Poole 12 Charley Trippi 13 Tom Fears 14 Paul Brown 15 Leon Hart 16 Frank Gifford 17 Y.A. Tittle 18 Charlie Justice 19 George Connor 20 Lynn Chandnois 21 Bill Howton 22 Kenneth Snyder 23 Gino Marchetti 24 John Karras 25 Tank Younger 26 Tommy Thompson 27 Bob Miller 28 Kyle Rote 29 Hugh McElhenny 30 Sammy Baugh 31 Jim Dooley 32 Ray Mathews 33 Fred Cone 34 Al Pollard 35 Brad Ecklund 36 John Lee Hancock 37 Elroy Hirsch 38 Keever Jankovich 39 Emlen Tunnell 40 Steve Dowden 41 Claude Hipps 42 Norm Standlee 43 Dick Todd Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Babe Parilli 45 Steve Van Buren 46 Art Donovan 47 Bill Fischer 48 George Halas 49 Jerrell Price 50 John Sandusky 51 Ray Beck 52 Jim Martin 53 Joe Bach 54 Glen Christian 55 Andy Davis 56 Tobin Rote 57 Wayne Millner 58 Zollie Toth 59 Jack Jennings 60 Bill McColl 61 Les Richter 62 Walt Michaels 63 Charley Conerly 64 Howard Hartley 65 Jerome Smith 66 James Clark 67 Dick Logan 68 Wayne Robinson 69 James Hammond 70 Gene Schroeder 71 Tex Coulter 72 John Schweder 73 Vitamin Smith 74 Joe Campanella 75 Joe Kuharich 76 Herman Clark 77 Dan Edwards 78 Bobby Layne 79 Bob Hoernschemeyer 80 Jack Carr Blount 81 John Kastan 82 Harry Minarik 83 Joe Perry 84 Ray Parker 85 Andy Robustelli 86 Dub Jones 87 Mal Cook 88 Billy Stone 89 George Taliaferro 90 Thomas Johnson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

Sportsnews1961january Dece

" UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND ATHLETICS MINNEAPOLIS 14 i-~'HHHHHHHHHHHHH'~-lHHHHHHHHHHl* 1961 GOIF BROCHURE "The Gophers" The Schedule March 2(}.21 Rice at Houston, Texas April 26 Carleton Here May 6 Iowa, Wisconsin at Iowa City May 19-20 Conference Meet at Bloomington, Ind. June 19-24 NCAA Meet at Lafayette, Ind. 1960 Minnesota Golf Results Minn. Opp. 23t St. Thomas 3} 16~ Maca1ester l~ 17 Hamline 1 29 Iowa 25 15 Wisconsin 21 27 Wisconsin 201. 22 Northwestern 13 181 Iowa 171 20 Alumni 10 21 Minneapolis Golf Club 15 Placed Fourth in Conference Meet *****i'MHHHh\~<iHHHH.YHHP,******",HHHHHHHfo This brochure was prepared by the Sports Information Office, University of Minnesota. For further information contact Otis'J. Dypwick, Sports Information Director, Room 208 Cooke Hall, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis 14, Minnesota. - 2·- 1961 MINNESOTA GOLF PROSPECTS "Minnesota's golf outlook is the brightest in years.IV That optimistic statement is how veteran Gopher coach Les Bolstad views his team's prospects for the 1961 season. riAnything can happen in the Big 10, but we're aiming for as high as we can go,a Bolstad declares. Biggest factors in the rosy outlook, according to Bolstad, are experience and balance. The Gophers top four men, Gene Hansen, Capt. Carson Herron, Rolf Deming, and Jim Pfleider are extremely well matched, and Bolstad says he can't chose between them as to excellence. The other members of the squad's top six are Harry Newby and Les Peterson. Bolstad hopes his squad will continue the great improvement demonstrated last year when the Gophers catapulted from ninth to fourth place and almost finished second. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

1961 Fleer Football Set Checklist

1961 FLEER FOOTBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Ed Brown ! 2 Rick Casares 3 Willie Galimore 4 Jim Dooley 5 Harlon Hill 6 Stan Jones 7 J.C. Caroline 8 Joe Fortunato 9 Doug Atkins 10 Milt Plum 11 Jim Brown 12 Bobby Mitchell 13 Ray Renfro 14 Gern Nagler 15 Jim Shofner 16 Vince Costello 17 Galen Fiss 18 Walt Michaels 19 Bob Gain 20 Mal Hammack 21 Frank Mestnik RC 22 Bobby Joe Conrad 23 John David Crow 24 Sonny Randle RC 25 Don Gillis 26 Jerry Norton 27 Bill Stacy 28 Leo Sugar 29 Frank Fuller 30 Johnny Unitas 31 Alan Ameche 32 Lenny Moore 33 Raymond Berry 34 Jim Mutscheller 35 Jim Parker 36 Bill Pellington 37 Gino Marchetti 38 Gene Lipscomb 39 Art Donovan 40 Eddie LeBaron 41 Don Meredith RC 42 Don McIlhenny Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 L.G. Dupre 44 Fred Dugan 45 Billy Howton 46 Duane Putnam 47 Gene Cronin 48 Jerry Tubbs 49 Clarence Peaks 50 Ted Dean RC 51 Tommy McDonald 52 Bill Barnes 53 Pete Retzlaff 54 Bobby Walston 55 Chuck Bednarik 56 Maxie Baughan RC 57 Bob Pellegrini 58 Jesse Richardson 59 John Brodie RC 60 J.D. Smith RB 61 Ray Norton RC 62 Monty Stickles RC 63 Bob St.Clair 64 Dave Baker 65 Abe Woodson 66 Matt Hazeltine 67 Leo Nomellini 68 Charley Conerly 69 Kyle Rote 70 Jack Stroud 71 Roosevelt Brown 72 Jim Patton 73 Erich Barnes 74 Sam Huff 75 Andy Robustelli 76 Dick Modzelewski 77 Roosevelt Grier 78 Earl Morrall 79 Jim Ninowski 80 Nick Pietrosante RC 81 Howard Cassady 82 Jim Gibbons 83 Gail Cogdill RC 84 Dick Lane 85 Yale Lary 86 Joe Schmidt 87 Darris McCord 88 Bart Starr 89 Jim Taylor Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com©