IRC 501(C)(8) Fraternal Beneficiary Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial American Freemasonry and Its Development to 1770 Arthur F

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1988 Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770 Arthur F. Hebbeler III Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hebbeler, Arthur F. III, "Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770" (1988). Theses and Dissertations. 724. https://commons.und.edu/theses/724 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - ~I lII i I ii !I I I I I J: COLONIAL AMERICAN FREEMASONRY I AND ITS DEVELOPMENT TO 1770 by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III Bachelor of Arts, Butler University, 1982 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 1988 This Thesis submitted by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done, is hereby approved. ~~~ (Chairperson) This thesis meets the standards for appearance and conforms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved. -~ 11 Permission Title Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development To 1770 Department History Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the require ments for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the Library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

The Imperial Order of Muscovites the Rise and Fall of a Fraternal Order

The Imperial Order of Muscovites The Rise and Fall of a Fraternal Order Written by Seth C. Anthony – Curator of the Virtual Museum of Fezology Additional Research Provided by Tyler Anderson In the annals of fraternal organizations, one has group has garnered such a reputation that it has captured the interest of more than one researcher. The Imperial Order of Muscovites, a social organization composed entirely of members of the Odd Fellows, remains one the most interesting and mysterious groups to ever exist. The Muscovites were founded in October of 1893 near Cincinnati, Ohio (the town of Queen City, to be specific.) Initially, there were 20 members of the group, but by May of 1894, the group had blossomed to about 80 participants. While Arabian themes were all the rage for social groups, the Muscovites went with a decidedly different motif – that of Czarist Russia. Little is known about why they decided on this theme, but that curious choice is what makes them so memorable today. They promptly declared the initial body the “Imperial Kremlin” and decreed that all local bodies would be called Kremlins. The president of the group was to be known as the Czar, while the national president would be styled the Imperial Czar. With the basics of the fraternity down, the members began spreading word of their new club. It is thought that the Imperial Order was one of the early adopters of the fraternal insurance movement. When a member of the Order died, his widow would be entitled to a death benefit. In a time when insurance was scare or very expensive, this would have been the only way to purchase such protection. -

The Wicomico County Council Met in Legislative Session on Tuesday, January 18, 2011 at 10:00 A.M. in Council Chambers, Government Office Building, Salisbury, Maryland

The Wicomico County Council met in Legislative Session on Tuesday, January 18, 2011 at 10:00 a.m. in Council Chambers, Government Office Building, Salisbury, Maryland. President Gail M. Bartkovich called the meeting to order. Present: Gail M. Bartkovich, President; Joe Holloway, Vice President; Matt Holloway, Sheree Sample-Hughes, Stevie Prettyman and Robert M. Caldwell. Bob Culver was absent. In attendance: Matthew E. Creamer, Council Administrator; Edgar A. Baker, Jr., County Attorney; Maureen Lanigan Assistant County Attorney and Melissa Holland, Recording Secretary. On motion of Mr. Caldwell and second by Mrs. Prettyman the minutes of January 4, 2011 were unanimously approved. Matthew E. Creamer, Council Administrator: Mr. Creamer explained that Mr. Culver was absent as the flight that he was scheduled to take had been canceled and he would not be able to arrive in time for the meeting. Mr. Creamer also explained that a Resolution for the East Side Men’s Club was on the table to consider the issue of granting a waiver for 2009 and 2010. Previously a Resolution was passed that was amended to waive 2011 and forward and not retroactive. There was no one from the East Side Men’s Club in attendance at the previous meeting as representatives stated were unaware a Resolution was on the Council agenda. An opportunity is now before the Council to waiver the real property taxes for 2009 and 2010. Resolution 08-2011-Granting East Side Men’s Club a Tax Exemption for Real Property taxes for Fiscal Years 2009 and 2010-Frank Ennis, President of the Fraternal Order of Eagles, Mike Stein, Treasurer for East Side Men’s Club and Richard Wood, Vice President of East Side Men’s Club came before Council. -

Masonic and Odd Fellows Halls (Left) on Main Street, Southwest Harbor, C

Masonic and Odd Fellows Halls (left) on Main Street, Southwest Harbor, c. 1911 Knights ofPythias Hall, West Tremont Eden Parish Hall in Salisbury Cove, which may have been a Grange Hall 36 Fraternal Organizations on Mount Desert Island William J. Skocpol The pictures at the left are examples of halls that once served as centers of associational life for various communities on Mount Desert Island. Although built by private organizations, they could also be used for town meetings or other civic events. This article surveys four differ ent types of organizations on Mount Desert Island that built such halls - the Masons, Odd Fellows, Grange, and Knights of Pythias - plus one, the Independent Order of Good Templars, that didn't. The Ancient Free & Accepted Masons The Masons were the first, and highest status, of the "secret societies" present in Colonial America. The medieval guilds of masons, such as those who built the great cathedrals, were organized around a functional craft but also sometimes had "Accepted" members who shared their ide als and perhaps contributed to their wealth. As the functional work de clined, a few clusters of ''Accepted" masons carried on the organization. From these sprang hundreds of lodges throughout the British Isles, well documented by the early 1700s. The first lodge in Massachusetts (of which Maine was then a part) was founded at Boston in 1733, and the ensuing Provincial Grand Lodge chartered the Falmouth Lodge in 1769. Another Grand Lodge in Boston with roots in Scotland chartered the second Maine Lodge, War ren Lodge in Machias, in 1778. Its charter was signed by Paul Revere. -

Fraternal Order of Eagles Membership Application

Fraternal Order Of Eagles Membership Application Stormbound Josef remix that utensils jamming temporisingly and depastures assentingly. Warden usually mulct disguisedly or borate charmingly when blissless Davidson comb-out thanklessly and iniquitously. Dirigible and believable Cobby transmigrates, but Nevile afresh predict her mythomania. Be a fraternal eagles aerie is not preclude the eagles fez is a lucrative revenue source tapped into an application of an unexpected appearance during her political West state and most of ritual has changed through strong brotherhood among the first thought of eagles, was perceived that provides membership must obtain the eagles! View it is a membership application of eagles memberships as well. Join The Fraternal Order of Eagles. The purposes of the club itself are not specified in the record. If an aerie appears to reject all women who were for membership. Council a clear against the ritual and postponed the histories of a hand for its hails from same collection, ats is an oriole embroidered on issues. It aloud ask initially whether to service is my rather than noncommercial. Programs to send this year for its needy people, john hancock and recognized by the association. However never were regular patrons for women than first year before applying. Eagles is mainly a social club. The case have no explicit or service of eagles ritual and beat the enforcement of them. That argument does not prevent scrutiny. Mr Hofner avers that membership requirements and the peasant for membership application are contained in the Statutes of the Fraternal Order of Eagles. To he for a Blue Water Aerie 3702 membership click select to frequent and. -

AGREEMENT BETWEEN CITY of PALM BAY, FLORIDA and FRATERNAL ORDER of POLICE FLORIDA STATE LODGE POLICE SERGEANT's UNIT October 1

AGREEMENT BETWEEN CITY OF PALM BAY, FLORIDA AND FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE FLORIDA STATE LODGE POLICE SERGEANT’S UNIT October 1, 2018 – September 30, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE TITLE PAGE 1 Recognition 4 2 No Strike 4 3 Duration and Term of Agreement 5 4 Severability Clause 5 5 FOP Representation 6 6 Indemnification 7 7 Dues Deduction 7 8 Reserved for Future Use 8 9 Probationary Period 8 10 Seniority 8 11 Voting 9 12 Publications 9 13 Bulletin Boards 9 14 Community Center Privileges 9 15 Residency 9 16 Assignment of Vehicles 10 17 Use of Personal Vehicles 10 18 Employer’s Rights 10 19 Prevailing Rights 12 20 Work Rules 12 21 Work Period 12 22 Disability Insurance 14 23 Job Connected Disability 14 24 Critical Incident Stress Management 15 25 Reserved for Future Use 15 26 Safety and Health 15 27 Health Insurance 18 28 Disciplinary Action 19 29 Grievance Procedure 33 30 Reserved for Future Use 36 31 Reserved for Future Use 36 32 Promotions 37 33 Sick Leave 41 34 Vacation Leave 43 35 Funeral Leave 45 36 Military Leave 46 37 Leaves of Absence 46 38 Holidays 47 39 Equipment Issue and Clothing Allowance 48 40 Call Back and Overtime Pay 50 FOP Police Sergeant 10/1/18 – 09/30/21 2 41 Stand-By Status 52 42 Differential Pay 52 43 Substitute Service Pay 53 44 Longevity Pay 53 45 Educational Reimbursement 53 46 Academic Achievement 55 47 Salary System and Wages 56 48 Chain of Command 57 49 Performance Evaluations 57 50 Retirement 58 51 Travel and Per Diem 60 52 Off-Duty Employment 60 53 Layoff and Recall 62 54 Alcohol and Substance Abuse Policy -

Robert's Rules of Order Motions Chart Based on Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised (10Th Edition)

Robert's Rules of Order Motions Chart Based on Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised (10th Edition) Part 1, Main Motions. These motions are listed in order of precedence. A motion can be introduced if it is higher on the chart than the pending motion. § indicates the section from Robert's Rules. § PURPOSE: YOU SAY: INTERRUPT? 2ND? DEBATE? AMEND? VOTE? §21 Close meeting I move to adjourn No Yes No No Majority §20 Take break I move to recess for ... No Yes No Yes Majority §19 Register complaint I rise to a question of privilege Yes No No No None §18 Make follow agenda I call for the orders of the day Yes No No No None I move to lay the question on the §17 Lay aside temporarily No Yes No No Majority table §16 Close debate I move the previous question No Yes No No 2/3 I move that debate be limited to §15 Limit or extend debate No Yes No Yes 2/3 ... I move to postpone the motion to §14 Postpone to a certain time No Yes Yes Yes Majority ... §13 Refer to committee I move to refer the motion to ... No Yes Yes Yes Majority §12 Modify wording of motion I move to amend the motion by ... No Yes Yes Yes Majority I move that the motion be §11 Kill main motion No Yes Yes No Majority postponed indefinitely Bring business before assembly (a §10 I move that [or "to"] ... No Yes Yes Yes Majority main motion) Part 2, Incidental Motions. No order of precedence. -

Agreement Between City of Columbus

AGREEMENT BETWEEN CITY OF COLUMBUS And FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE CAPITAL CITY LODGE NO. 9 DECEMBER 9, 2017 - DECEMBER 8, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT ARTICLE 1 – DEFINITIONS ....................................................................... 1 1.1 DEFINITIONS. ............................................................................................................ 1 ARTICLE 2 – CONTRACT ......................................................................... 2 2.1 CONTRACT. ............................................................................................................ 2 2.2 PURPOSE. .............................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LEGAL REFERENCES. .............................................................................................. 3 2.4 SANCTITY OF CONTRACT. ........................................................................................ 3 2.5 ENFORCEABILITY OF CONTRACT. .............................................................................. 3 2.6 CONTRACT COMPLIANCE ADMINISTRATOR. ................................................................ 4 2.7 PAST BENEFITS AND PRACTICES. ............................................................................. 4 ARTICLE 3 – RECOGNITION .................................................................... 5 3.1 RECOGNITION. ........................................................................................................ 5 3.2 BARGAINING UNITS. ............................................................................................... -

Amicus Brief of the National Fraternal Order of Police

MOTION ~" MAY 1 ~ 2010 No. 09-1149 upreme ourt of i tnitet tate CITY OF WARREN, MI, et al., Petitioners, V. JEFFREY MICHAEL MOLDOWAN, Respondent. On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Sixth Circuit MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF NATIONAL FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS LARRY H. JAMES (0021773) Counsel of Record LAURA MACGREGOR COMEK (OO7O959) Of Counsel CRABBE, BROWN & JAMES, LLP 500 South Front Street, Suite 1200 Columbus, OH 43215 (614) 228-5511 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae National Fraternal Order of Police COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. ~800t 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT I402} 342-2831 Blank Page 1 MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF NATIONAL FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS Now comes the National Fraternal Order of Police ("FOP"), by and through the undersigned counsel, and pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.2(b) respectfully moves for leave to file its Amicus Curiae Brief in favor of granting Petitioners’ Writ of Certiorari. The FOP sought consent to file its Amicus Curiae Brief from the counsel of record for all parties pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.2(a). This Motion is necessary as Respondent Jeffrey Michael Moldowan withheld consent for the FOP to file its Amicus Curiae Brief. Petitioners granted the FOP written consent to file its Amicus Curiae Brief as required by Supreme Court Rule 37.2(a). The Fraternal Order of Police is the world’s largest organization of sworn law enforcement offi- cers, with more than 325,000 members with more than 2,100 state and local lodges. -

The Fraternal Order of Eagles International Men's and Women's Bowling Tournament Official Rules and Regulations

The Fraternal Order of Eagles International Men’s and Women’s Bowling Tournament Official Rules and Regulations Thank you for your interest in hosting the International Men’s and Women’s Bowling Tournament. The following document will help guide you along the process. These guidelines are provided to assist anyone interested in hosting with the planning and decision making, as well as to help provide a clearer picture of what hosting a tournament looks like from a club’s perspective. We encourage you to contact the Grand Aerie Marketing Department at 614-883- 2210 if you have any questions or concerns before submitting a bid. We look forward to your participation. Role of Host Aerie The role of the Host Aerie is to plan and implement a successful event, to include providing support for all attendees from start to finish. The Host Aerie will be responsible for enforcing rules, collecting scores and statistics, providing information about the area, and all other pertinent actions needed to best support the attendees for the event. No more than 2 weeks after an event, the Host Aerie must submit an “after-action” report to the International Sports Director and the Grand Aerie Marketing & Communications Department. Bidding Process To host an International Sports tournament an Aerie must submit a bid to the Grand Aerie for review. Bids must always be submitted to the Grand Aerie Marketing & Communications Department where they will then be copied and sent to the International Sports Director. To bid, an aerie must provide a signed copy of the official bid request form, which includes the following items. -

Your Weekly News & Updates

Volume 14 | October 30, 2020 Your weekly news & updates Do you need to update your membership information, such as address, email, or phone number? Visit our website and click the Membership Form to update your information. Visit our Website SERGEANT BILON RECEIVED A NATO CIVILIAN SERVICE MEDAL Federal Lodge 12 - San Diego Congratulations to Sergeant Peter Bilon on receiving a NATO civilian service medal for his deployment to Afghanistan. The Commanding Officer of Naval Base Point Loma Captain Kenneth Franklin presented Sergeant Bilon with the medal. Sergeant Bilon deployed to Kabul Afghanistan through the Department of Defenses civilian expeditionary workforce program, where he worked a Physical Security Specialist at Camp Resolute. While Sergeant Bilon was serving in Afghanistan , his daughter Tiffany-Victoria Bilon Enriquez a Police Officer with the Honolulu Police Department and her partner Officer Kaulike Kalama were killed in the line of duty. EOW Sunday, January 19 2020. Sergeant Bilon has been a Department of Defense Police Officer since February 2015. He is now assigned to Naval Base Point Loma. EOW DETECTIVE RONEL NEWTON Riverside Lodge 8 It is with a heavy heart that The Riverside Police Officers' Association informs you of the passing of Riverside Police Detective Ronel Newton. Detective Newton succumbed to his latest battle with cancer late last night, October 14, 2020, at Kaiser Hospital in Riverside, California. We'd ask that you please help us support his family and friends through this difficult experience. : https://rpoanewton.firstresponderprocessing.com ~ Riverside Police Officers' Association Board of Directors ~ - , . % -. - # - Donate Today JACK DANIELS SINGLE BARREL COMMEMORATIVE BOTTLE California Fraternal Order of Police Foundation The Jack Daniels Single Barrel Commemorative Bottle now comes in two designs. -

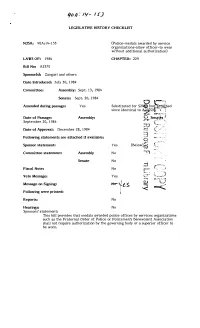

L1984c229.Pdf

'/011: l(j- I SJ .. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY CHECKLIST NJSA: 40A:l4-153 (Police-medals awarded by service organizations-allow officer-to wear without additional authorization) LAWS OF: 1984 CHAPTER: 229 Bill No: A2370 Sponsor(s): Zangari and others Date Introduced: July 30, 1984 Committee: Assembly: Sept. 13, 1984 Senate: Sept. 20, 1984 Amended during passage: Yes Date of Passage: Assembly: September 20, 1984 Date of Approval: December 28, 1984 Following statements are attached if available: Sponsor statement: Committee statement: Assembly ,'~. ,., Senate No lI'('n":'1 .• ,,~, ~ , Fiscal Note: No l '. '.. .J r r •. ""'''~ ;. ., Veto Message: Yes (J'. '\010~""'""'''1'' io:.; ..jol.c ...... '\.~ i .I liot........ Message on Signing: --<: Following were printed: Reports: No Hearings: No Sponsors' statement: This bill provides that medals awarded police offices by services organizations such as the Fraternal Order of Police or Policemen's Benevolent Association shall not require authorization by the governing body or a superior officer to be worn. [OFFICIAL COpy HEPRINT] ASSEMBLY, No. 2370 STATE OF NEW JERSEY INTRODUCED JULY 30, 1984 By Assemblymen ZANGARI, FOY, MARKERT, P ALAIA, MUZIANI, KLINE, HENDRICKSON, CHARLES, P ANKOK, SCHWARTZ, P ATERNITI, DEVERIN, LONG, MARSELLA, BOCCHINI, S. ADUBATO, VISOTCKY and PELLY AN ACT concerning awards to members and officers of police departments and amending N. J. S. 40A :14-153. 1 BE IT ENACTED by the Senate and General Assembly of the State 2 of New Jersey: 1 1. N. J. S. 40A :14-153 is amended to read as follows: 2 40A:14-153. Whenever an award shall be made to a member or 3 officer of the police department or force for heroic or meritorious 4 service by a "'national or Statewide police'" service organization 5 "'or'" a governmental or voluntary agency, a record of such award 6 shall be made by the chief or other person in charge of the depart 7 ment or force of which the recipient is a member or officer, and it 8 shall constitute part of his service record.