Longevity and Displacement Records from the South African Bird Ringing Scheme for Ardeidae, Threskiornithidae and Ciconiidae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bear River Refuge

Bear River Refuge MIGRATION MATTERS Summary Student participants increase their understanding of migration and migratory birds by playing Migration Matters. This game demonstrates the main needs Grade Level: (habitat, food/water, etc.) for migratory birds, and several of the pitfalls and 1 - 6 dangers of NOT having any of those needs readily available along the migratory flyway. Setting: Outside – pref. on grass, or large indoor Objectives - “Students will…” space with room to run. ● understand the concept of Migration / Migratory birds and be able to name at least two migratory species Time Involved: 20 – 30 min. ● indentify three reasons/barriers that explain why “Migration activity, 5 – 10 min. setup isn’t easy” (example: loss of food, habitat) Key Vocabulary: Bird ● describe how invasive species impact migratory birds Migration, Flyways, Wetland, Habitat, Invasive species Materials ● colored pipe-cleaners in rings to represent “food” Utah Grade Connections 5-6 laminated representations of wetland habitats 35 Bird Name tags (1 bird per student; 5 spp / 7 ea) 2 long ropes to delineate start/end of migration Science Core Background Social Studies Providing food, water, and habitat for migratory birds is a major portion of the US FWS & Bear River MBR’s mission. Migratory birds are historically the reason the refuge exists, and teaching the students about the many species of migratory birds that either nest or stop-off at the refuge is an important goal. The refuge hosts over 200 migratory species including large numbers of Wilson’s phalaropes, Tundra swans and most waterfowl, and also has upwards of 70 species nesting on refuge land such as White-faced ibis, American Avocet and Grasshopper sparrows. -

The Cuckoo Sheds New Light on the Scientific Mystery of Bird Migration 20 November 2015

The cuckoo sheds new light on the scientific mystery of bird migration 20 November 2015 Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen led the study with the use of miniature satellite tracking technology. In an experiment, 11 adult cuckoos were relocated from Denmark to Spain just before their winter migration to Africa was about to begin. When the birds were released more than 1,000 km away from their well-known migration route, they navigated towards the different stopover areas used along their normal route. "The release site was completely unknown to the cuckoos, yet they had no trouble finding their way back to their normal migratory route. Interestingly though, they aimed for different targets on the route, which we do not consider random. This individual and flexible choice in navigation indicates an ability to assess advantages and disadvantages of different routes, probably based on their health, age, experience or even personality traits. They evaluate their own condition and adjust their reaction to it, displaying a complicated behavior which we were able to document for the first time in migratory birds", says postdoc Mikkel Willemoes from the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen. Previously, in 2014, the Center also led a study mapping the complete cuckoo migration route from Satellite technology has made it possible for the first Denmark to Africa. Here they discovered that time to track the complete migration of a relocated during autumn the birds make stopovers in different species and reveal individual responses. Credit: Mikkel areas across Europe and Africa. -

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small Seabird in a Changing Environment Renata Jorge Medeiros Mirra September 2010 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University UMI Number: U516649 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516649 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declarations & Statements DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed j K>X).Vr>^. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 1 This thasjs is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree o f ..................... (insertMCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed . .Ate .^(candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledgedjjy explicit references. Signe .. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

Migratory Bird Day Educator's Supplement

Dear Educator, elcome to the International Migratory Bird Day Educator’s Supplement. The Supplement provides activities and direction to Wadditional resources needed to teach students about migratory birds. The activities are appropriate for grade levels three through eight and can be used in classrooms as well as in informal educational settings. Birds offer virtually endless opportunities to teach and learn. For many, these singing, colorful, winged friends are the only form of wildlife that students may experience on a regular basis. Wild birds seen in backyards, suburban neighborhoods, and urban settings can connect children to the natural world in ways that captive animals cannot. You may choose to teach one activity, a selection of activities, or all five activities. If you follow the complete sequence of activities, the Supplement is structured to lead students through an Adopt-a-Bird Project. Detailed instruc- tions for the Adopt-a-Bird Project are provided (Getting Started, p. 9). Your focus on migratory birds may be limited to a single day, to each day of IMBD week, or to a longer period of time. Regardless of the time period you choose, we encourage you to consider organizing or participating in a festival for your school, organization, or community during the week of International Migratory Bird Day, the second Saturday of May. The IMBD Educator’s Supplement is a spring board into the wondrous, mysterious, and miraculous world of birds and their migration to other lands. There are many other high quality migratory bird curriculum products currently available to support materials contained in the Supplement. -

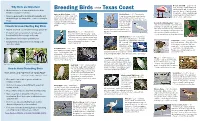

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and Area

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and area Reproduced with kind permission of Etienne Marais of Indicator Birding Visit www.birding.co.za for more info and details of birding tours and events Endemic birds KEY: SA = South African Endemic, SnA = Endemic to Southern Africa, NE = Near endemic (Birders endemic) to the Southern African Region. RAR = Rarity Status KEY: cr = common resident; nr = nomadic breeding resident; unc = uncommon resident; rr = rare; ? = status uncertain; s = summer visitor; w = winter visitor r Endemicity Numbe Sasol English Status All Scientific p 30 Little Grebe cr Tachybaptus ruficollis p 30 Black-necked Grebe nr Podiceps nigricollis p 56 African Darter cr Anhinga rufa p 56 Reed Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax africanus p 56 White-breasted Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax lucidus p 58 Great White Pelican nr Pelecanus onocrotalus p 58 Pink-backed Pelican ? Pelecanus rufescens p 60 Grey Heron cr Ardea cinerea p 60 Black-headed Heron cr Ardea melanocephala p 60 Goliath Heron cr Ardea goliath p 60 Purple Heron uncr Ardea purpurea p 62 Little Egret uncr Egretta garzetta p 62 Yellow-billed Egret uncr Egretta intermedia p 62 Great Egret cr Egretta alba p 62 Cattle Egret cr Bubulcus ibis p 62 Squacco Heron cr Ardeola ralloides p 64 Black Heron uncs Egretta ardesiaca p 64 Rufous-bellied Heron ? Ardeola rufiventris RA p 64 White-backed Night-Heron rr Gorsachius leuconotus RA p 64 Slaty Egret ? Egretta vinaceigula p 66 Green-backed Heron cr Butorides striata p 66 Black-crowned Night-Heron uncr Nycticorax nycticorax p -

Front Cover.Jpg

African Openbill (Openbilled Near Threatened to Least Concern in South Africa (Taylor Stork) | Anastomus lamelligerus et al. in press), where it breeds only sporadically. Woolly-necked Stork | Ciconia episcopus © Ken Oake Game Studios (Botswana) Pty Ltd Game Studios Oake © Ken and Lake Liambezi. On rare occasions it is recorded as a vagrant to dams and coastal wetlands among the more common Great White Pelican P. onocrotalus. Only four breeding colonies are known: one in the Salambala Conservancy on the Chobe River floodplain, where about 25 birds were recorded in August 1998 (RE Simmons, M Paxton pers. obs.) and 125 birds in September 2001 (Ward 2001), and two from the Linyanti Swamps. The average number of nests per colony was 26 (22 to 34) and eggs were laid in Endemic to sub-Saharan wetlands, avoiding forests © Ken Oake Game Studios (Botswana) Pty Ltd Game Studios Oake © Ken July and August (Brown et al. 2015). The global population, (del Hoyo et al. 1992), this species is found in northern spread across sub-Saharan Africa and the southern Red Widespread in Africa south of the Sahara, this species Namibia, mainly along perennial rivers and floodplains, Sea, is estimated at 50,000 to 100,000 birds (Dodman occurs mainly in the Okavango Delta in Botswana and as well as in the Cuvelai drainage system, sometimes This is a widespread species throughout sub-Saharan 2002). The Namibian population is less than 1% of the on rivers and large protected areas in Zimbabwe and in large flocks when pans such as Etosha are flooded. Africa and India, through to the Philippines (del Hoyo et African population. -

Great Egret Ardea Alba

Great Egret Ardea alba Joe Kosack/PGC Photo CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the great egret is listed state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migra- tory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: The Pennsylvania Game Commission counts active great egret (Ardea alba) nests in every known colony in the state every year to track changes in population size. Since 2009, only two nesting locations have been active in Pennsylvania: Kiwanis Lake, York County (fewer than 10 pairs) and the Susquehanna River’s Wade Island, Dauphin County (fewer than 200 pairs). Both sites are Penn- sylvania Audubon Important Bird Areas. Great egrets abandoned other colonies along the lower Susque- hanna River in Lancaster County in 1988 and along the Delaware River in Philadelphia County in 1991. Wade Island has been surveyed annually since 1985. The egret population there has slowly increased since 1985, with a high count of 197 nests in 2009. The 10-year average count from 2005 to 2014 was 159 nests. First listed as a state threatened species in 1990, the great egret was downgraded to endan- gered in 1999. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS: Great egrets are almost the size of a great blue heron (Ardea herodias), but white rather than gray-blue. From bill to tail tip, adults are about 40 inches long. The wingspan is 55 inches. The plumage is white, bill yellowish, and legs and feet black. Commonly confused species include cattle egret (Bubulus ibis), snowy egret (Egretta thula), and juvenile little blue herons (Egretta caerulea); however these species are smaller and do not nest regularly in the state. -

A Major Waterbird Breeding Colony at Lake Urema, Gorongosa National Park, Moçambique

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279953019 A MAJOR WATERBIRD BREEDING COLONY AT LAKE UREMA, GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, MOÇAMBIQUE Article · January 2015 CITATIONS READS 0 49 4 authors, including: Marc Stalmans Gorongosa National Park, Mocambique 25 PUBLICATIONS 192 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Marc Stalmans on 10 July 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 54 GORONGOSA WATERBIRDS Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 37 A MAJOR WATERBIRD BREEDING COLONY AT LAKE UREMA, GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, MOÇAMBIQUE STALMANS M.1, DAVIES G.B.P.* 2, TROLLIP J. 1 & POOLE G. 1 1 Gorongosa Restoration Project, Chitengo, Sofala Province, Moçambique 2 Ditsong National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 413, Pretoria, South Africa *Author for correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] talmans, M., Davies, G.B.P., Trollip, J. & Poole, G. 2014. A major waterbird breeding colony at Lake Urema, Gorongosa National SPark, Moçambique. Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 37: 54-57. A very large breeding colony of eight waterbird species, comprising 5003 nests and active over March and April 2014 in flooded (0.5-1 m deep), open Faidherbia-Acacia woodland, is described from Lake Urema, Gorongosa National Park, Moçambique. The colony contained breeding Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis (983 nests), African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus (531 nests), Reed Cormorant Phalacrocorax africanus (2276 nests), African Darter Anhinga rufa (547 nests), Great Egret Egretta alba (330 nests), White-breasted Cormorant (230 nests), Grey Heron Ardea cinerea (82 nests) and African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus (24 nests). -

MADAGASCAR: the Wonders of the “8Th Continent” a Tropical Birding Set Departure

MADAGASCAR: The Wonders of the “8th Continent” A Tropical Birding Set Departure November 3—28, 2013 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken during this trip. All photos by Ken Behrens unless noted otherwise. TOUR SUMMARY Madagascar has long been a core destination for Tropical Birding, and with last year’s opening of a satellite office in the country, we have further solidified our expertise in the “Eighth Continent.” This was another highly successful set-departure tour to this special island. It included both the Northwestern Endemics Pre-Trip at the start and the Helmet Vanga extension to the Masoala Peninsula at the end. Although Madagascar poses some logistical challenges, especially in the form of the national airline Air Madagascar, we had no problems on this tour, not even a single delayed flight! The birding was great, with 196 species recorded, including almost all of the island’s endemic birds. As usual, the highlight was seeing all five of the incredible ground-rollers, from the roadrunner-like Long-tailed of the spiny forest to the wonderful rainforest-dwelling Scaly. There was a strong cast of vangas, including Helmet, Bernier’s, and Sickle-billed. In fact, we saw every member of the family save the mysterious Red-tailed Newtonia which is only regularly seen in the far south. As normal, the couas were also a favorite. From the shy and beautiful Red-breasted of Madagascar Set Departure Tour Nov. 3-28, 2013 the eastern rainforest to the huge Giant Coua of the dry western forest, we were looking for and at couas virtually every day! The bizarre mesites form a Malagasy endemic family, and we had superb extended views of all three members of the family. -

Bird Migration in South Florida

BIRD MIGRATION IN SOUTH FLORIDA Many gardeners appreciate the natural world beyond plants and create landscapes with the intention of attracting and sustaining wildlife, particularly birds. Birds provide added interest, and often color, to the garden. In Miami-Dade county, there are familiar birds who reside here year round including the ubiquitous Northern Cardinal, Blue Jay and Northern Mockingbird, while others visit only during periods of migration. The fall migration of birds heading south to warmer climates for the winter usually begins in September and lasts well into November. The relatively warm weather of south Florida means that some bird species returning to their spring breeding grounds to the north can begin to be seen here as early as January, although February is generally regarded as the start of the spring migratory season. For some birds south Florida is a way station on their flight south to take advantage of warmer winter weather in the southern hemisphere. Others, such as the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher and the Palm WarBler, migrate to south Florida and make our area their winter home. The largest grouping of migratory birds seen here are the warBlers. While many have the word “warbler” in their names, others do not. They do share the distinction of being rather small birds – from the 4 ½ inch Northern Parula to the 6 inch Ovenbird – with most warblers measuring around 5 inches in length. Many warbler names reflect the color of their feathers, e.g., the Black-throated Blue Warbler and the Black-and-white Warbler. The Ovenbird gets its name from the dome shape of its nest built on the ground. -

Cattle Egret Bubulcus Ibis the Cattle Egret Has Enjoyed the Most Explosive Natural Range Expansion of Any Bird in Recorded His- Tory

Herons and Bitterns — Family Ardeidae 139 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis The Cattle Egret has enjoyed the most explosive natural range expansion of any bird in recorded his- tory. In 25 years it went from being a new arrival to the most abundant bird in southeastern California’s Imperial Valley. In San Diego County, however, it has seen a reversal as well as an advance. Since the spe- cies first nested in 1979, colonies have formed and vanished in quick succession; from 1997 through 2001 the only important one was that at the Wild Animal Park. After a peak in the 1980s the popula- tion has been on the decline; the conversion of pas- tures and dairies to urban sprawl spells no good for this bird whose lifestyle is linked to livestock. Breeding distribution: The Cattle Egret colony at the Wild Animal Park (J12) is part of the mixed-species heronry in the Heart of Africa exhibit—a site eminently Photo by Anthony Mercieca suitable for this species of African origin. Maximum numbers reported here in the breeding season during the Beyond a 15-mile radius of the Wild Animal Park, the atlas period were 100 individuals on 15 June 1998 (D. and Cattle Egret is uncommon and irregular, especially during D. Bylin) and 43 nests on 9 May 1999 (K. L. Weaver). the breeding season. It is still rather frequent in the San Luis In 2001, one or two pairs nested in the multispecies Rey River valley between Oceanside and Interstate 15 (up to heronry at Lindo Lake, Lakeside (P14).