State of the Geotags: Motivations and Recent Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geotagging: an Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision

Geotagging: An Innovative Tool To Enhance Transparency and Supervision Transparency through Geotagging Noel Sta. Ines Geotagging Geotagging • Process of assigning a geographical reference, i.e, geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) + elevation - to an object. • This could be done by taking photos, nodes and tracks with recorded GPS coordinates. • This allows geo-tagged object or SP data to be easily and accurately located on a map. WhatThe is Use Geotagging and Implementation application in of the Geo Philippines?-Tagging • A revolutionary and inexpensive approach of using ICT + GPS applications for accurate visualization of sub-projects • Device required is only a GPS enabled android cellphone, and access to freely available apps • Easily replicable for mainstreaming to Government institutions & CSOs • Will help answer the question: Is the right activity implemented in the right place? – (asset verification tool) Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geotagging Example No. 1: Visualization of a farm-to-market road in a conflict area: showing specific location, ground distance, track / alignment, elevation profile, ground photos (with coordinates, date and time taken) of Farm-to-market Road, i.e. baseline information + Progress photos + 3D visualization Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geotagging Example No. 2: Location and Visualization of rehabilitation of a city road in Earthquake damaged-area in Tagbilaran, Bohol, Philippines by the auditors and the citizen volunteers Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geo-tagging Example No. 3 Visualization of a water supply project showing specific location, elevation profile from the source , distribution lines and faucets, and ground photos of community faucets Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geo-tagging Example No. -

Geotagging Photos to Share Field Trips with the World During the Past Few

Geotagging photos to share field trips with the world During the past few years, numerous new online tools for collaboration and community building have emerged, providing web-users with a tremendous capability to connect with and share a variety of resources. Coupled with this new technology is the ability to ‘geo-tag’ photos, i.e. give a digital photo a unique spatial location anywhere on the surface of the earth. More precisely geo-tagging is the process of adding geo-spatial identification or ‘metadata’ to various media such as websites, RSS feeds, or images. This data usually consists of latitude and longitude coordinates, though it can also include altitude and place names as well. Therefore adding geo-tags to photographs means adding details as to where as well as when they were taken. Geo-tagging didn’t really used to be an easy thing to do, but now even adding GPS data to Google Earth is fairly straightforward. The basics Creating geo-tagged images is quite straightforward and there are various types of software or websites that will help you ‘tag’ the photos (this is discussed later in the article). In essence, all you need to do is select a photo or group of photos, choose the "Place on map" command (or similar). Most programs will then prompt for an address or postcode. Alternatively a GPS device can be used to store ‘way points’ which represent coordinates of where images were taken. Some of the newest phones (Nokia N96 and i- Phone for instance) have automatic geo-tagging capabilities. These devices automatically add latitude and longitude metadata to the existing EXIF file which is already holds information about the picture such as camera, date, aperture settings etc. -

Geotag Propagation in Social Networks Based on User Trust Model

1 Geotag Propagation in Social Networks Based on User Trust Model Ivan Ivanov, Peter Vajda, Jong-Seok Lee, Lutz Goldmann, Touradj Ebrahimi Multimedia Signal Processing Group Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Motivation 2 We introduce users in our system for geotagging in order to simulate a real social network GPS coordinates to derive geographical annotation, which are not available for the majority of web images and photos A GPS sensor in a camera provides only the location of the photographer instead of that of the captured landmark Sometimes GPS and Wi-Fi geotagging determine wrong location due to noise http: //www.pl acecas t.net Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Motivation 3 Tag – short textual annotation (free-form keyword)usedto) used to describe photo in order to provide meaningful information about it User-provided tags may sometimes be spam annotations given on purpose or wrong tags given by mistake User can be “an algorithm” http://code.google.com/p/spamcloud http://www.flickr.com/photos/scriptingnews/2229171225 Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Goal 4 Consider user trust information derived from users’ tagging behavior for the tag propagation Build up an automatic tag propagation system in order to: Decrease the anno ta tion time, and Increase the accuracy of the system http://www.costadevault.com/blog/2010/03/listening-to-strangers Multimedia -

UC Berkeley International Conference on Giscience Short Paper Proceedings

UC Berkeley International Conference on GIScience Short Paper Proceedings Title Tweet Geolocation Error Estimation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0wf6w9p9 Journal International Conference on GIScience Short Paper Proceedings, 1(1) Authors Holbrook, Erik Kaur, Gupreet Bond, Jared et al. Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.21433/B3110wf6w9p9 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California GIScience 2016 Short Paper Proceedings Tweet Geolocation Error Estimation E. Holbrook1, G. Kaur1, J. Bond1, J. Imbriani1, C. E. Grant1, and E. O. Nsoesie2 1University of Oklahoma, School of Computer Science Email: {erik; cgrant; gkaur; jared.t.bond-1; joshimbriani}@ou.edu 2University of Washington, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Email: [email protected] Abstract Tweet location is important for researchers who study real-time human activity. However, few studies have examined the reliability of social media user-supplied location and description in- formation, and most who do use highly disparate measurements of accuracy. We examined the accuracy of predicting Tweet origin locations based on these features, and found an average ac- curacy of 1941 km. We created a machine learning regressor to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the textual content of these fields, and obtained an average accuracy of 256 km. In a dataset of 325788 tweets over eight days, we obtained city-level accuracy for approximately 29% of users based only on their location field. We describe a new method of measuring location accuracy. 1. Introduction With the rise of micro-blogging services and publicly available social media posts, the problem of location identification has become increasingly important. -

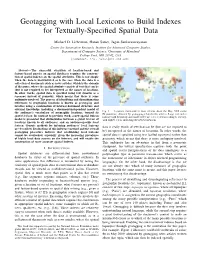

Geotagging with Local Lexicons to Build Indexes for Textually-Specified Spatial Data

Geotagging with Local Lexicons to Build Indexes for Textually-Specified Spatial Data Michael D. Lieberman, Hanan Samet, Jagan Sankaranarayanan Center for Automation Research, Institute for Advanced Computer Studies, Department of Computer Science, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742, USA {codepoet, hjs, jagan}@cs.umd.edu Abstract— The successful execution of location-based and feature-based queries on spatial databases requires the construc- tion of spatial indexes on the spatial attributes. This is not simple when the data is unstructured as is the case when the data is a collection of documents such as news articles, which is the domain of discourse, where the spatial attribute consists of text that can be (but is not required to be) interpreted as the names of locations. In other words, spatial data is specified using text (known as a toponym) instead of geometry, which means that there is some ambiguity involved. The process of identifying and disambiguating references to geographic locations is known as geotagging and involves using a combination of internal document structure and external knowledge, including a document-independent model of the audience’s vocabulary of geographic locations, termed its Fig. 1. Locations mentioned in news articles about the May 2009 swine flu pandemic, obtained by geotagging related news articles. Large red circles spatial lexicon. In contrast to previous work, a new spatial lexicon indicate high frequency, and small circles are color coded according to recency, model is presented that distinguishes between a global lexicon of with lighter colors indicating the newest mentions. locations known to all audiences, and an audience-specific local lexicon. -

Geotagging Tweets Using Their Content

Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference Geotagging Tweets Using Their Content Sharon Paradesi Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract Harnessing rich, but unstructured information on social networks in real-time and showing it to relevant audi- ence based on its geographic location is a major chal- lenge. The system developed, TwitterTagger, geotags tweets and shows them to users based on their current physical location. Experimental validation shows a per- formance improvement of three orders by TwitterTag- ger compared to that of the baseline model. Introduction People use popular social networking websites such as Face- book and Twitter to share their interests and opinions with their friends and the online community. Harnessing this in- formation in real-time and showing it to the relevant audi- ence based on its geographic location is a major challenge. Figure 1: Architecture of TwitterTagger The microblogging social medium, Twitter, is used because of its relevance to users in real-time. The goal of this research is to identify the locations refer- Pipe POS tagger1. The noun phrases are then compared with enced in a tweet and show relevant tweets to a user based on the USGS database2 of locations. Common noun phrases, that user’s location. For example, a user traveling to a new such as ‘Love’ and ‘Need’, are also place names and would place would would not necessarily know all the events hap- be geotagged. To avoid this, the system uses a greedy ap- pening in that place unless they appear in the mainstream proach of phrase chunking. -

TAGGS: Grouping Tweets to Improve Global Geotagging for Disaster Response Jens De Bruijn1, Hans De Moel1, Brenden Jongman1,2, Jurjen Wagemaker3, Jeroen C.J.H

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2017-203 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 13 June 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC BY 3.0 License. TAGGS: Grouping Tweets to Improve Global Geotagging for Disaster Response Jens de Bruijn1, Hans de Moel1, Brenden Jongman1,2, Jurjen Wagemaker3, Jeroen C.J.H. Aerts1 1Institute for Environmental Studies, VU University, Amsterdam, 1081HV, The Netherlands 5 2Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, World Bank Group, Washington D.C., 20433, USA 3FloodTags, The Hague, 2511 BE, The Netherlands Correspondence to: Jens de Bruijn ([email protected]) Abstract. The availability of timely and accurate information about ongoing events is important for relief organizations seeking to effectively respond to disasters. Recently, social media platforms, and in particular Twitter, have gained traction as 10 a novel source of information on disaster events. Unfortunately, geographical information is rarely attached to tweets, which hinders the use of Twitter for geographical applications. As a solution, analyses of a tweet’s text, combined with an evaluation of its metadata, can help to increase the number of geo-located tweets. This paper describes a new algorithm (TAGGS), that georeferences tweets by using the spatial information of groups of tweets mentioning the same location. This technique results in a roughly twofold increase in the number of geo-located tweets as compared to existing methods. We applied this approach 15 to 35.1 million flood-related tweets in 12 languages, collected over 2.5 years. In the dataset, we found 11.6 million tweets mentioning one or more flood locations, which can be towns (6.9 million), provinces (3.3 million), or countries (2.2 million). -

An Introduction to Georss: a Standards Based Approach for Geo-Enabling RSS Feeds

Open Geospatial Consortium Inc. Date: 2006-07-19 Reference number of this document: OGC 06-050r3 Version: 1.0.0 Category: OpenGIS® White Paper Editors: Carl Reed OGC White Paper An Introduction to GeoRSS: A Standards Based Approach for Geo-enabling RSS feeds. Warning This document is not an OGC Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an OGC Standard. Recipients of this document are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting do Document type: OpenGIS® White Paper Document subtype: White Paper Document stage: APPROVED Document language: English OGC 06-050r3 Contents Page i. Preface – Executive Summary........................................................................................ iv ii. Submitting organizations............................................................................................... iv iii. GeoRSS White Paper and OGC contact points............................................................ iv iv. Future work.....................................................................................................................v Foreword........................................................................................................................... vi Introduction...................................................................................................................... vii 1 Scope.................................................................................................................................1 -

From RDF to RSS and Atom

From RDF to RSS and Atom: Content Syndication with Linked Data Alex Stolz Martin Hepp Universität der Bundeswehr München Universität der Bundeswehr München E-Business and Web Science Research Group E-Business and Web Science Research Group 85577 Neubiberg, Germany 85577 Neubiberg, Germany +49-89-6004-4277 +49-89-6004-4217 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT about places, artists, brands, geography, transportation, and related facts. While there are still quality issues in many sources, For typical Web developers, it is complicated to integrate content there is little doubt that much of the data could add some value from the Semantic Web to an existing Web site. On the contrary, when integrated into external Web sites. For example, think of a most software packages for blogs, content management, and shop Beatles fan page that wants to display the most recent offers for applications support the simple syndication of content from Beatles-related products for less than 10 dollars, a hotel that wants external sources via data feed formats, namely RSS and Atom. In to display store and opening hours information about the this paper, we describe a novel technique for consuming useful neighborhood on its Web page, or a shopping site enriched by data from the Semantic Web in the form of RSS or Atom feeds. external reviews or feature information related to a particular Our approach combines (1) the simplicity and broad tooling product. support of existing feed formats, (2) the precision of queries Unfortunately, consuming content from the growing amount of against structured data built upon common Web vocabularies like Semantic Web data is burdensome (if not prohibitively difficult) schema.org, GoodRelations, FOAF, SIOC, or VCard, and (3) the for average Web developers and site owners, for several reasons: ease of integrating content from a large number of Web sites and Even in the ideal case of having a single SPARQL endpoint [2] at other data sources of RDF in general. -

![Arxiv:1810.03067V1 [Cs.IR] 7 Oct 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1412/arxiv-1810-03067v1-cs-ir-7-oct-2018-1771412.webp)

Arxiv:1810.03067V1 [Cs.IR] 7 Oct 2018

Geocoding Without Geotags: A Text-based Approach for reddit Keith Harrigian Warner Media Applied Analytics Boston, MA [email protected] Abstract that will require more thorough informed consent processes (Kho et al., 2009; European Commis- In this paper, we introduce the first geolocation sion, 2018). inference approach for reddit, a social media While some social platforms have previously platform where user pseudonymity has thus far made supervised demographic inference dif- approached the challenge of balancing data access ficult to implement and validate. In particu- and privacy by offering users the ability to share lar, we design a text-based heuristic schema to and explicitly control public access to sensitive at- generate ground truth location labels for red- tributes, others have opted not to collect sensitive dit users in the absence of explicitly geotagged attribute data altogether. The social news website data. After evaluating the accuracy of our la- reddit is perhaps the largest platform in the lat- beling procedure, we train and test several ge- ter group; as of January 2018, it was the 5th most olocation inference models across our reddit visited website in the United States and 6th most data set and three benchmark Twitter geoloca- tion data sets. Ultimately, we show that ge- visited website globally (Alexa, 2018). Unlike olocation models trained and applied on the real-name social media platforms such as Face- same domain substantially outperform models book, reddit operates as a pseudonymous website, attempting to transfer training data across do- with the only requirement for participation being mains, even more so on reddit where platform- a screen name. -

A Patent for Geotagging IP Packets Raises Important Internet Law Questions

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Media & Informal Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-15-2018 A Patent For Geotagging IP Packets Raises Important Internet Law Questions Marketa Trimble University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facmedia Part of the Communications Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Trimble, Marketa, "A Patent For Geotagging IP Packets Raises Important Internet Law Questions" (2018). Media & Informal Publications. 14. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facmedia/14 This Blog Post is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Browse: Home » 2018 » January » A Patent For Geotagging IP Packets Raises Important Internet Law Questions (Guest Blog Post) A Patent For Geotagging IP Packets Raises Important Internet Law Questions (Guest Blog Post) January 15, 2018 · by Eric Goldman · in Content Regulation, Internet History, Patents by guest blogger Marketa Trimble Enter Destination On September 12, 2017, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued a patent on a technology that Check in Check out could significantly affect the functioning of the internet and the course of internet-related law and mm/dd/yy m policy, and achieve an ultimate territorialization[FN] of the internet. SEARCH NOW [FN: “Territorialization” -

Camera User Guide Playback Mode Wi-Fi Functions

Before Use Basic Guide Advanced Guide Camera Basics Auto Mode Other Shooting Modes P Mode Camera User Guide Playback Mode Wi-Fi Functions Setting Menu Accessories • Make sure you read this guide, including the “Safety • Click the buttons in the lower right to access other pages. Appendix ENGLISH Precautions” (= 6) section, before using the camera. : Next page • Reading this guide will help you learn to use the camera : Previous page Index properly. : Page before you clicked a link • Store this guide safely so that you can use it in the • To jump to the beginning of a chapter, click the chapter future. title at right. From chapter title pages, you can access topics by clicking their titles. © CANON INC. 2016 CT0-D050-000-F101-B 1 Before Use Package Contents Preliminary Notes and Legal Basic Guide Before use, make sure the following items are included in the package. Information If anything is missing, contact your camera retailer. Advanced Guide • Take and review some test shots initially to make sure the images were recorded correctly. Please note that Canon Inc., its subsidiaries and Camera Basics affiliates, and its distributors are not liable for any consequential damages arising from any malfunction of a camera or accessory, including memory Auto Mode cards, that result in the failure of an image to be recorded or to be Other Shooting recorded in a way that is machine readable. Camera Battery Pack Battery Charger Modes NB-11L* CB-2LF/CB-2LFE Images recorded by the camera shall be for personal use. Refrain from • P Mode unauthorized recording that infringes on copyright law, and note that even for personal use, photography may contravene copyright or other Playback Mode legal rights at some performances or exhibitions, or in some commercial Printed Matter settings.