The Struggles Faced by Austin Area Professional Sports Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

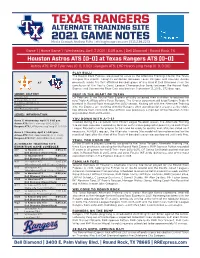

TEXAS RANGERS ALTERNATE TRAINING SITE 2021 GAME NOTES Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213

TEXAS RANGERS ALTERNATE TRAINING SITE 2021 GAME NOTES Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213 Game 1 | Home Game 1 | Wednesday, April 7, 2021 | 6:05 p.m. | Dell Diamond | Round Rock, TX Houston Astros ATS (0-0) at Texas Rangers ATS (0-0) Astros ATS: RHP Tyler Ivey (0-0, 0.00) | Rangers ATS: LHP Hyeon-jong Yang (0-0, 0.00) PLAY BALL! The Round Rock Express are proud to serve as the Alternate Training Site for the Texas Rangers this month. Tonight’s exhibition between Texas Rangers and Houston Astros AT prospects marks the first affiliated baseball game of any kind at Dell Diamond since the conclusion of the Pacific Coast League Championship Series between the Round Rock Express and Sacramento River Cats way back on September 13, 2019... 572 days ago. SERIES HISTORY DEEP IN THE HEART OF TEXAS Overall: 0-0 On February 9, the Round Rock Express officially accepted their invitation to become the In Round Rock: 0-0 new Triple-A affiliate of the Texas Rangers. The 10-year agreement will keep Rangers Triple-A In Corpus Christi: 0-0 baseball in Round Rock through the 2030 season. Kicking off with the Alternate Training Streak: -- Site, the Express are reuniting with the Rangers after spending eight seasons as the club’s One-Run Games: 0-0 top affiliate from 2011-2018. Round Rock was previously a member of the Houston Astros organization from 2019-2020. SERIES INFORMATION YOU DOWN WITH A-T-S? Game 1 | Wednesday, April 7 | 6:05 p.m. -

Mountaineers in the Pros

MOUNTAINEERS IN THE PROS Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Team/League Years Stedman BAILEY ALEXANDER, ROBERT (77-78-79-80) Los Angeles Rams (NFL) 1981-83 Los Angeles Express (USFL) 1985 ANDERSON, WILLIAM (43) Boston Yanks (NFL) 1945 ATTY, ALEXANDER (36-37-38) New York Giants (NFL) 1948 AUSTIN, TAVON (2009-10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAILEY, RUSSELL (15-16-17-19) Akron Pros (APFA) 1920-21 BAILEY, STEDMAN (10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAISI, ALBERT (37-38-39) Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-41,46 Philadelphia Eagles (NFL) 1947 BAKER, MIKE (90-91-93) St. Louis Stampede (AFL) 1996 Albany Firebirds (AFL) 1997 Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Grand Rapids Rampage (AFL) 1998-2002 Team/League Years Team/League Years BARBER, KANTROY (94-95) BRAXTON, JIM (68-69-70) CAMPBELL, TODD (79-80-81-82) New England Patriots (NFL) 1996 Buffalo Bills (NFL) 1971-78 Arizona Wranglers (USFL) 1983 Carolina Panthers (NFL) 1997 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1978 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1998-99 CAPERS, SELVISH (2005-06-07-08) BREWSTER, WALTER (27-28) New York Giants (NFL) 2012 BARCLAY, DON (2008-09-10-11C) Buffalo Bisons (NFL) 1929 Green Bay Packers 2012-13 CARLISS, JOHN (38-39-40) BRIGGS, TOM (91-92) Richmond Rebels (DFL) 1941 BARNUM, PETE (22-23-25-26) Anaheim Piranhas (AFL) 1997 Columbus Tigers (NFL) 1926 CLARKE, HARRY (37-38-39) Portland Forest Dragons (AFL) 1997-99 Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-43 BARROWS, SCOTT (82-83-84) Oklahoma Wranglers (AFL) 2000-01 San Diego Bombers (PCFL) 1945 Detroit Lions (NFL) 1986-87 Dallas Desperados (AFL) 2002-03 Los -

William & Mary Football Record Book

William & Mary CONTENTS & QUICK FACTS Football Record Book as of June 1, 2020 CONTENTS Contents . 1 Tribe in the Pros . 2-3 Honors & Awards . 6-9 Records . 10-11 Individual Single-Season Records . 12-13 Individual Career Records . 14 All-Time Top Performances . 15 Team Game Records . 16 Team Season Records . 17 The Last Time … . 18-22 All-Time Coaches & Captains . 23-24 All-Time Series Results . 25-26 All-Time Results . 27-33 All-Time Assistant Coaches . 34 All-Time Roster . 35-46 WWW.TRIBEATHLETICS.COM 1 TRIBE IN THE PROS B.W. Webb Luke Rhodes DeAndre Houston-Carson Cincinnati Bengals Indianapolis Colts Chicago Bears Name Pro Team Years Dave Corley, Jr . Hamilton Tiger-Cats 2003-04 R .J . Archer Minnesota 2010 Calgary Stampeders 2006 Milwaukee Mustangs 2011 Jerome Couplin III Detroit Lions 2014 Georgia Force 2012 Buffalo Bills 2014 Detroit Lions 2012 Philadelphia Eagles 2014-15 Jacksonville Sharks 2013-14 Los Angeles Rams 2016 Seattle Seahawks 2015 Hamilton Tiger-Cats 2018 Drew Atchison Dallas Cowboys 2008 Orlando Apollos 2019 Bill Bowman Detroit Lions 1954, 1956 Los Angeles Wildcats 2020 Pittsburgh Steelers 1957 Derek Cox Jacksonville Jaguars 2009-12 Tom Brown Pittsburgh Steelers 1942 San Diego Chargers 2013 Russ Brown Honolulu Hawaiians 1974 Minnesota Vikings 2014 New York Giants 1974 Baltimore Ravens 2014 Washington Redskins 1975 New England Patriots 2015 Todd Bushnell Baltimore Colts 1973 Lou Creekmur Detroit Lions 1950-59 David Caldwell Indianapolis Colts 2010-11 Dan Darragh Buffalo Bills 1968-70 New York Giants 2013 DeVonte Dedmon -

Vols in Pro Football

2007 TENNESSEE VOLUNTEERS FOOTBALL Contacts: Bud Ford (cell 865-567-6287) Assoc. AD-Media Relations John Painter (cell 865-414-1143) Assoc. SID P.O. Box 15016 Knoxville, TN 37901 Phone: (865) 974-1212 Fax: (865) 974-1269 [email protected] [email protected] 2007 TEN N ESSEE SC H EDULE Game 13 Date Opponent Time/Result Tennessee Volunteers vs. LSU Tigers Sept. 1 at California (ABC) L 31-45 Sept. 8 Southern Mississippi (PPV) W 39-19 Dec. 1 Georgia Dome (71,250) 4 p.m. ET CBS Sept. 15 *at Florida (CBS) L 20-59 Sept. 22 Arkansas State (PPV) W 48-27 TENNESSEE LSU Oct. 6 *Georgia (CBS) W 35-14 UTsports.com Web Site LSUsports.net Oct. 13 *at Mississippi State (PPV) W 33-21 9-3, 6-2 SEC Record 10-2, 6-2 SEC Oct. 20 *at Alabama (LF) L 17-41 14th AP / 15th USA Today Coaches Ranking 5th AP / 7th USA Today Coaches Oct. 27 *South Carolina (ESPN) (OT) W 27-24 Phillip Fulmer (Tennessee, 1972) Head Coach Les Miles (Michigan, 1976) Nov. 3 Louisiana-Lafayette (HC) W 59-7 146-44 (.768, 16th year) Overall Record 60-27 (.690, Seventh year) Nov. 10 *Arkansas (LF) W 34-13 146-44 (.768, 16th year) Record at School 32-6 (.842, Third year) Nov. 17 *Vanderbilt (PPV) W 25-24 Tennessee leads 20-6-3 All-Time Series Nov. 24 *at Kentucky (CBS) (4OT) W 52-50 Dec. 1 vs. LSU (SEC Champ.) (CBS) 4 p.m. ET DID YOU KNOW? * Southeastern Conference game Tennessee was the only team in the SEC to go undefeated at home this season. -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

Illustrative Plan2

VISION Illustrative Plan2 23 CITY OF ROUND ROCK DOWNTOWN MASTER PLAN JANUARY 2010 24 CITY OF ROUND ROCK DOWNTOWN MASTER PLAN JANUARY 2010 A VISION FOR ROUND ROCK Downtown Round Rock can become a thriving town center featuring a viable mix of residential, commercial, retail, dining, entertainment and public space uses in a walkable and historically- sensitive environment to enhance Round Rock’s economy, quality of life, and sense of place. 25 CITY OF ROUND ROCK DOWNTOWN MASTER PLAN JANUARY 2010 MASTER VISION PLAN In order to achieve an activated and attractive downtown, the Master Public Space Plan proposes a series of physical design interventions that seek a A quarter mile from the town green is a cultural and history museum or vibrant urban realm. Together these proposals seek to create a Round restaurant and galleries in the Nelson-Crier House (a National Register- Rock “brand” and identity. designated historic property currently under private ownership) and ¼ mile from this is the Round Rock Community Foundation property (old Downtown Main Street ball fields), which should be designed as a combination of At the center of the downtown is a new town green around the historic open space and uses for the Round Rock Community Foundation. The Round Rock water tower. The town green, which is created via a property should be comprehensively planned to effectively integrate realignment of Round Rock Avenue, is surrounded by pedestrian-oriented these uses. retail and commercial uses, such as restaurants with outdoor seating. The town green becomes the focal point of downtown, accommodating Brushy Creek is re-programmed with an extended park and Heritage festivals, farmer’s markets, and other events that draw both locals and Trail, connecting to the larger Round Rock trail system and over the visitors. -

Location Overview Texas Round Rock 128739

FIRESTONE COMPLETE AUTO CARE Brand New 15-Year Corp. Absolute NNN Lease Adjacent to HEB, LA Fitness, and St. David’s HIGHLY DESIRABLE N. AUSTIN SUBURB Medical (171 Beds) $4,643,000 | 4.75% CAP 3 Miles From Dell Technologies World HQ (11,100 Employees) 17300 N RM 620, Round Rock, TX 78681 (Austin) Round Rock Ranks #2 Money Magazine Best Places to Live in US - Sept 2019 INVESTMENT OVERVIEW FIRESTONE | ROUND ROCK, TEXAS $4,643,000 | 4.75% CAP CONTACT FOR DETAILS ALEX TOWER $220,519 6,116 SF 0.88 ACRES Senior Associate NOI BUILDING AREA LAND AREA (214) 915-8892 [email protected] 2020 100% ABSOLUTE NNN YR BUILT / RENOVATED OCCUPANCY LEASE TYPE JOE CAPUTO Estimated Store Opening March 2020 Managing Partner (424) 220-6432 Absolute NNN lease with 5% increases every 5-years, in primary term and options. [email protected] Strategically located along RM 620 "Round Rock Ave" (42,000 + VPD), just north of where RM 620 intersects with O'Connor Drive (17,000 + VPD) Avg HH Income & Population (3-Mi. Radius) - $120k/70k The immediate trade area features above-average Household Incomes and population density. Within a 3-mile radius of the site, there are an estimated 70,000 people and average Household incomes exceed $120,000 This information has been secured from sources we believe to be reliable but we make no Close Proximity to Major National Credit Tenants. Nationally recognized credit representations or warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy of the information. Buyer must tenants along the same stretch of RM 620 include HEB, Starbucks, LA Fitness, 7- verify the information and bears all risk for any Eleven, Jiffy Lube and many more inaccuracies. -

2014 Orlando Predators Media Guide

2014 MEDIA GUIDE THIS NEEDS TO BE FIXED TABLE OF CONTENTS AND PLEASE 2013 Season Schedule Orlando Predators History TV Broadcasting Schedule Conference Year by Year History ADD THE Division Alignment Opponents Team Records Administration Team Playoff Records Individual Records BROADCAST- Team Directory Individual Playoff Records Managing Member, Brett Bouchy Top Single Game Performances Rookie Records Department Head Bios Opponent Records Career Leaders ING SCHED- Staff Single Season Leaders Year-By-Year Stats Media Information Series Scores/Records All-Time Roster (’91 – ’12) Covering the Predators Amway Center All-Time Coaches All-Time Awards ULE TO THIS Coaching Staff Ring of Honor Head Coach Doug Plank Arena Football League AF1 Mission Statement PAGE Associate Head Coach Tim Marcum Support Fans Bill of Rights 2012 Teams Map Playoff Staff Format Roster 2012 Composite Schedule Commissioner Jerry Numerical Roster Alphabetical Roster Player Kurz Bios Rules of the Game 2012 Review Final Stats Team/Individual Highs Opponent Highs Game Summaries OPPONENT BREAKDOWN OPPENENT BREAKDOWN OPPENENT BREAKDOWN Orlando Predators Arizona Rattlers Cleveland Gladiators Iowa Barnstormers Jacksonville Sharks Los angeles kiss CFE Arena (10,000) US Airways Center (18,422) Quicken Loans Arena (20,562) Wells Fargo Arena (16,980) Jacksonville Veterans Memorial Arena Honda Center (18,336) 12777 Gemini Blvd. N 201 East Jefferson St One Center Court, 730 3rd Street 300 A. Philip Randolph Boulevard 2695 E Katella Ave Orlando, FL 32816 Phoenix, AZ, 85004 Cleveland, -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational -

2017 Houston Football Media Guide Uhcougars.Com Houstonfootball Media Information

HOUSTONFOOTBALL HOUSTON FOOTBALL 2017 SEASON 2017 >> 2017 OPPONENTS COACHING STAFF SEPTEMBER 2 SEPTEMBER 9 SEPTEMBER 16 SEPTEMBER 23 AT UTSA AT ARIZONA RICE TEXAS TECH Date: Sept. 2, 2017 Date: Sept. 9, 2017 Date: Sept. 16, 2017 Date: Sept. 23, 2017 Location: San Antonio, Texas Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: TDECU Stadium Location: TDECU Stadium THE COUGARS Series: Series tied 1-1 Series: Series tied 1-1 Series: Houston leads 29-11 Series: Houston leads 18-11-1 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: UTSA 27, Houston 7 | 2014 Arizona 37, Houston 3 | 1986 Houston 31, Rice 26 | 2013 Texas Tech 35, Houston 20 | 2010 SEPTEMBER 30 OCTOBER 7 OCTOBER 14 OCTOBER 19 SEASON REVIEW AT TEMPLE SMU AT TULSA MEMPHIS Date: Sept. 30, 2017 Date: Oct. 7, 2017 Date: Oct. 14, 2017 Date: Oct. 19, 2017 Location: Philadelphia, Pa. Location: TDECU Stadium Location: Tulsa, Okla. Location: TDECU Stadium Series: Houston leads 5-0 Series: Houston leads 20-11-1 Series: Houston leads 23-18 Series: Houston leads 15-10 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Houston 24, Temple 13 | 2015 SMU 38, Houston 16 | 2016 Houston 38, Tulsa 31 | 2016 Memphis 48, Houston 44 | 2016 HISTORY & RECORDS HISTORY TM OCTOBER 28 NOVEMBER 4 NOVEMBER 18 NOVEMBER 24 EAST CAROLINA AT USF AT TULANE NAVY Date: Oct. 28, 2017 Date: Nov. 4, 2017 Date: Nov. 18, 2017 Date: Nov. 24, 2017 Location: TDECU Stadium Location: Tampa, Fla. Location: New Orleans, La. Location: TDECU Stadium Series: East Carolina leads 7-5 Series: Series tied 2-2 Series: Houston leads 16-5 Series: Houston leads 2-1 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: East Carolina 48, Houston 28 | 2012 Houston 27, USF 3 | 2014 Houston 30, Tulane 18 | 2016 Navy 46, Houston 40 | 2016 1 @UHCOUGARFB #HTOWNTAKEOVER HOUSTONFOOTBALL MEDIA INFORMATION HOUSTON ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS >> 2017 SEASON 2017 DAVID BASSITY JEFF CONRAD ALLISON MCCLAIN ROMAN PETROWSKI KYLE ROGERS ALEX BROWN SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD ASSISTANT AD DIRECTOR ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR TED NANCE COMMUNICATIONS ASST. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Welcome to Leander Drippinga City Guide Springs, for Locals & New Texas Neighbors

Welcome to Leander DrippingA City Guide Springs, For Locals & New Texas Neighbors Welcome to Leander, Texas, a vibrant community situated on the northern outskirts of Austin just 26 miles from downtown. Leander is a small town with a heart as big as Texas itself. It’s the 4th fastest growing city in the state and an idyllic place for those who seek plenty to do outdoors and a safe community to raise a family or retire. www.TexasNationalTitle.com Fitness Court at Leander, Texas Robin Bledsoe Park General City Information Schools: Leander ISD www.leanderisd.org County: Williamson www.wilco.org Elementary Schools City of Leander www.leandertx.gov Akin Elementary School 3261 Barley Road, Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-8000 Leander Chamber of Commerce 100 N Brushy St, Leander, TX 78641 Bagdad Elementary School (512) 259-1907 | www.leandercc.org 800 Deercreek Ln., Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-5900 Leander Municipal Court Block House Creek Elementary School 201 N Brushy St, Leander, TX 78641 401 Creek Run, Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-7600 (512) 259-1239 | www.leandertx.gov/municipalcourt Camacho Elementary School Leander Public Library 501 Municipal Dr., Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-7800 1011 S. Bagdad, Leander, TX 78641 (512) 259-5259 | www.leandertx.gov/library Larkspur Elementary School 424 Rusk Bluff Avenue, Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-8100 Post Office 801 S US-183, Leander, TX 78641 Plain Elementary School (800) 275-8777 | www.usps.com 501 South Brook Dr., Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-6600 Emergencies: 911 Pleasant Hill Elementary School Police: (512) 260-4600 1800 Horizon Park Blvd., Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-6400 Fire: (512) 539-3400 Whitestone Elementary School 2000 Crystal Fall Pkwy., Leander, TX 78641 | (512) 570-7400 Middle Schools Utilities: Leander Middle School 410 S.