Baseball Explained This Page Intentionally Left Blank Baseball Explained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Ran Into Pete Rose in Philly Airport a Couple of Months Ago

I ran into Pete Rose in Philly airport a couple of months ago. Not like he ran into Ray Fosse in the 1970 All-Star game though - because that would hurt. More about that game later. Pete was at his gate waiting for a flight to Cincinnati. (Naturally) But he was wearing a Phillies ball cap. (Interesting!). As a Canadian, I saw no need to approach him for any reason whatsoever. Canadians and Americans deal with celebrities differently. I went back to the restaurant and informed my American wife of nearby celebrity, evidently also informing the eavesdropping lady at the next table, and both of them practically dropped their forks to head over to the Cincy gate. I had actually met Rose before, as he signed baseball cards in a Vegas sport collectibles store. I remembered feeling sad for him. Which was odd, because his life has been such an incredible story - the fluky way he first got to the Majors; how he became one the greatest players ever, and still holds Major League records for games (3562), at-bats (14053), hits (4256), and singles (3215). Three World Series wins later he gets accused of betting on baseball games, including ones involving the Reds - while managing the Reds. He denies, denies....and then, 15 years later, admits to it in his biography. He got a life-time ban from baseball, and from consideration for the Hall of Fame. He was then relegated to a life of card signing, reality shows, and stunts. There were allegations of sexual relations with a minor, and he also did 5 months of jail time for failing to report income from memorabilia signings, receiving a conviction for tax evasion. -

Defensive Responsibilities

DEFENSIVE RESPONSIBILITIES http://www.baseballpositive.com/ "Baseball is a Game of Movement". This is a foreign concept for most youth baseball and softball players. If we could dig into the brain of ballplayers ages 5-12 right next to the idea of 'Baseball' we would find the phrase 'a game where you stand around a lot and don't do anything' (and we wonder why participation is dwindling). When the game is played properly each player on defense is moving (sprinting) the moment the ball comes off the bat. We can do a better job of teaching kids how to play the game. This section is dedicated to helping coaches teach kids their defensive responsibilities on each play regardless of where the ball is hit or where the runners are. Before digging in, let's add something to the old coaching comment, "Be sure you know what to do if the ball is hit to you". But the ball is hit to one player; what about the other eight? The must also teach our players, "Know what you are going to do when the ball is NOT hit to you". The first part of this section outlines in clear and simple terms, the 'Rules for Defensive Movement'. These rules form the foundation for the drills and concepts in the rest of this section. Some of the plays found here are not consistent with player responsibilities on the larger 80' or 90' diamonds. The game on the smaller diamond is slower and the players are not as strong. These facts combined with the shorter distance between the players and the bases makes this game quite different than the one played on the large diamond. -

Xvi: 3-Man Mechanics Standard Operating Procedures

XVI: 3-MAN MECHANICS STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES – 3-MAN CREWS ABBREVIATIONS: The plate umpire will be referred to as U1, the first-base umpire as U2, and the third-base umpire will be referred to as U3. It is assumed that in all play situations, U1 will start out behind the plate. There are four basic positions for the base umpires: positions A, B, C and D. These positions are described as follows, and will remain unchanged, regardless of the number of outs: Position A — Both feet in foul territory, approximately 10 feet behind the first baseman. Position B — At the infield cutout near second base, first-base side of the infield, feet parallel to the pitcher's plate, able to move to cover a pickoff attempt at second base. Position C — Halfway between the mound and second base, third-base side of the infield, feet parallel to the pitcher's plate, able to move to cover a pickoff attempt or attempted steal at either second base or third base. Position D — Both feet in foul territory, approximately 10 feet behind the third baseman. If covering a base with runners on, Positions A and D are modified somewhat in that the umpire on the baseline will move up closer to the base, still in foul territory, in order to get an angle on the pickoff attempt and line up the pitcher's foot crossing over the back edge of the pitcher's plate. GENERAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES: U1: 1. Call balls and strikes. 2. Rule fair/foul on any batted ball that is played on or comes to rest in front of the front edge of the base down the first-base line with U2 in Position A and down the third-base line with U3 in position D. -

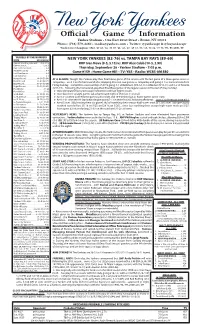

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr & @losyankeespr World Series Champions: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2013 (2012) NEW YORK YANKEES (82-76) vs. TAMPA BAY RAYS (89-69) Current Standing in AL East: . T3rd, -13 .5 RHP Ivan Nova (9-5, 3.13) vs. RHP Alex Cobb (10-3, 2.90) Current Streak: . .. Lost 3 Current Homestand: . 2-3 Thursday, September 26 • Yankee Stadium • 7:05 p.m. Recent Road Trip: . 4-6 Last Five Games: . 2-3 Game #159 • Home Game #81 • TV: YES • Radio: WCBS-AM 880 Last 10 Games: . 3-7 Home Record: . 46-34 (51-30) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play their final home game of the season with the last game of a three-game series vs . Road Record: . .36-42 (44-37) Tampa Bay… are 2-3 on the homestand after dropping their first two games vs . Tampa Bay and going 2-1 vs . San Francisco from Day Record: . .. 31-24 (32-20) Night Record: . 51-52 (63-47) Friday-Sunday… completed a 4-6 road trip on 9/19 going 3-1 at Baltimore (9/9-12), 0-3 at Boston (9/13-15) and 1-2 at Toronto Pre-All-Star . 51-44 (9/17-19)… following this homestand, play their final three games of the regular season at Houston (Friday-Sunday) . Post-All-Star . -

Blocking the Plate

Rule 7.13: COLLISIONS AT HOME PLATE. (1) A runner attempting to score may not deviate from his direct pathway to the plate in order to initiate contact with the catcher (or other player covering home plate). If, in the judgment of the umpire, a runner attempting to score initiates contact with the catcher (or other player covering home plate) in such a manner, the umpire shall declare the runner out (even if the player covering home plate loses possession of the ball). In such circumstances, the umpire shall call the ball dead, and all other base runners shall return to the last base touched at the time of the collision. • Score as Offensive Interference, per rule 10.09(c)(6) (2) Unless the catcher is in possession of the ball, the catcher cannot block the pathway of the runner as he is attempting to score. If, in the judgment of the umpire, the catcher without possession of the ball blocks the pathway of the runner, the umpire shall call or signal the runner safe. Notwithstanding the above, it shall not be considered a violation of this Rule 7.13 if the catcher blocks the pathway of the runner in order to field a throw, and the umpire determines that the catcher could not have fielded the ball without blocking the pathway of the runner and that contact with the runner was unavoidable. • Obstruction (Decisive Error) may be scored, but only if the blocking of the plate call changed what was going to happen – in the opinion of the scorer – if there had been no blocking of the plate, per rule 10.12(c) Comment. -

Traveling Skills & Drills

HUDSON BOOSTER CLUB Hudson Boosters TRAVELING TEAM SKILLS LIST COMPETITIVE TEAM SKILLS 1 COMPETITIVE TEAM SKILLS AND CONCEPTS The skills and concepts listed are the minimum skills that a person coming out of each program should possess. This list is not meant to limit the amount of skills that can be taught and demonstrated, rather, it is meant to provide a base of instruction for coaches. TEACHING SKILLS When you introduce a new skill, you should practice the IDEA method. I – Introduce the skill. Explain what you’re trying to accomplish D – Demonstrate the skill. E – Explain the mechanics of the skill. A – Activate the drill that reinforces the skill. HITTING SKILLS Stance / Swing Hitting the Pitch Bunting BASE RUNNING SKILLS Base running rules Proper running techniques Leading off base Sliding FIELDING SKILLS General Information Set Position Fielding Catching Throwing Infield Skills Infield Positions Outfield Skills Catcher Position PITCHING SKILLS Throwing Wind up and Delivery Pitching from the Set (stretch) position Fielding after the throw COMPETITIVE TEAM SKILLS 2 HITTING SKILLS Stance: Proper bat size Stand so that bat can reach the far side of Home plate Feet apart at a comfortable distance Swing Eyes on the ball Step towards the pitcher on the swing, drive with back leg. Keep both hands on the bat during the follow-through Level swing Hitting the Pitch Inside pitch - Pull the ball down the line Middle pitch - Hit straight away Outside pitch - Drive to opposite field Bunt (Sacrifice) Move upper hand towards end of bat Square to the pitcher during wind-up Know where to bunt on any situation BASE RUNNING SKILLS Base running rules LISTEN TO THE COACH After hitting the ball: Locate ball half way to 1st base Overrun 1st base on a hit to the infield "Flaring out" on a base hit half way to 1st base Rounding the base on a base hit Touching the inside of the bases when going extra bases On base: Taking a primary and secondary lead Primary lead is before ball is pitched. -

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book Table of Contents Lugnuts Media Guide Staff Directory ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Executive Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Midwest League Midwest League Map and Affiliation History .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bowling Green Hot Rods / Dayton Dragons ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Fort Wayne TinCaps / Great Lakes Loons ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Lake County Captains / South Bend Cubs ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 West Michigan Whitecaps ............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Youth Baseball Rules 8U, 10U, 12U Revised 3/24/2021 A

Youth Baseball Rules 8U, 10U, 12U Revised 3/24/2021 A. Ground Rules 1. Line up cards should always be exchanged before pregame during ground rules meeting. 2. The Home Team is the “official” scorebook for the game. Coaches are encouraged to check in every half inning to ensure accuracy of score, and pitch counts. 3. Only the Head Coach, a maximum of 2 assistant coaches and players on the roster are permitted in the dugout. In 8U only, an additional parent may be in the dugout controlling the team if the coach is needed to pitch. 4. The defensive players presently in the game, the batter, and two base coaches (1st and 3rd base) are the only personnel permitted on the field. In 8U, the coach pitcher/machine operator is allowed. All other coaches and players must remain in the dugout. The only exception would be in 8U where a coach is using the pitching machine. 5. Equipment must be kept in the dugout and off the field of play. PENALTY: For violation of Rules C3 – C4, obstruction or interference may be called against the offending team, and the umpire may impose appropriate penalties. 6. A ball thrown out of play is an immediate dead ball. The results of the play are the following: A. If it is the first throw by an infielder, the result will be two (2) bases from the runner’s position at the time of the pitch. B. If it is on any other throw (i.e. – 2nd or 3rd throw or a throw from the outfield), the result will be two bases from the base runners position at the time of release. -

Stepping Into Coaching 3 Coach and a Parent, and Think About How Those Roles Relate to Each Other

chapter 1 SteppingStepping IntoInto CoachingCoaching If you are like most youth league coaches, you have probably been recruited from the ranks of concerned parents, sport enthusiasts, or com- munity volunteers. Like many rookie and veteran coaches, you prob- ably have had little formal instruction on how to coach. But when the call went out for coaches to assist with the local youth baseball pro- gram, you answered because you like children and enjoy baseball, and perhaps because you wanted to be involved in a worthwhile commu- nity activity. Your initial coaching assignment may be difficult. Like many volun- teers, you may not know everything there is to know about baseball or about how to work with children. Coaching Youth Baseball will help you learn the basics of coaching baseball effectively. To start, let’s take a look at what’s involved in being a coach. What are your responsibilities? We’ll also talk about how to handle the situa- tion when your child is on the team you coach, and we’ll examine five tools for being an effective coach. 1 2 Coaching Youth Baseball Your Responsibilities As a Coach As a baseball coach, you’ll be called upon to do the following: 1. Provide a safe physical environment. Playing baseball holds an inherent risk, but as a coach you’re responsible for regularly inspecting the practice and competition fields (see the checklists for facilities and equipment in chapter 6). 2. Communicate in a positive way. You’ll communicate not only with your players but also with parents, umpires, and administrators. -

Shetland Division (4-, 5-, & 6-Year-Olds)

Meadows Place PONY Baseball Ground Rules Shetland Division (4-, 5-, & 6-year-olds) Managers are required to have a copy of the rules in their possession for each game. PONY Baseball rules (https://www.pony.org/Default.aspx?tabid=1026027) and MLB rules shall apply unless otherwise specified. Objectives . Shetland Division focuses on instruction of beginning players. Managers and coaches will teach players to properly swing a bat, catch, throw and run the bases. Players are encouraged to experience different positions throughout the season. Sportsmanship . Unsportsmanlike behavior will not be tolerated. Umpires will maintain control and have the authority to eject or remove players, coaches, or fans from the facility. Umpires should not be approached after the game under any circumstances. Any manager, coach, player, or fan demonstrating unsportsmanlike behavior may be ejected from the game and may be suspended for additional games. Razzing, heckling, chanting, or making disparaging remarks or noises directed at opponents in any manner is prohibited. Shakers or noise makers are not allowed. For the safety of all players and to maintain integrity of the game, organized cheering or chanting is not allowed while the batter is preparing to hit the ball. Like all rules, enforcement is subject to umpire judgment. Foul and abusive language will not be tolerated under any circumstances. Cursing or throwing equipment is grounds for an automatic ejection. There is a zero-tolerance policy for making threats or taking physical action. Any occurrence will be immediately reported to the Board and the proper authorities. Declared League Age . As part of the League registration, each player MUST declare a league age (determined by their age on May 1) for the up coming season. -

356 Baseball for Dummies, 4Th Edition

Index 1B. See fi rst–base position American Association, 210 2B. See second–base position American League (AL), 207. 3B. See third–base position See also stadiums 40–40 club, 336 American Legion Baseball, 197 anabolic steroids, 282 • A • Angel Stadium of Anaheim, 280 appeal plays, 39, 328 Aaron, Hank, 322 appealing, 328 abbreviations appearances, defi ned, 328 player, 9 Arizona Diamondbacks, 265 scoring, 262 Arizona Fall League, 212 across the letters, 327 Arlett, Buzz, 213 activate, defi ned, 327 around the horn, defi ned, 328 adjudged, defi ned, 327 artifi cial turf, 168, 328 adjusted OPS (OPS+), 243–244 Asian leagues, 216 advance sale, 327 assists, 247, 263, 328 advance scouts, 233–234, 327 AT&T Park, 272, 280 advancing at-balls, 328 hitter, 67, 70, 327 at-bats, 8, 328 runner, 12, 32, 39, 91, 327 Atlanta Braves, 265–266 ahead in the count, defi ned, 327 attempts, 328. See also stealing bases airmailed, defi ned, 327 automatic outs, 328 AL (American League) teams, 207. away games, 328 See also stadiums alive balls, 32 • B • alive innings, 327 All American Amateur Baseball Babe Ruth League, 197 Association, 197 Babe Ruth’s curse, 328 alley (power alley; gap), 189, 327, 337 back through the box, defi ned, 328 alley hitters, 327 backdoor slide, 328 allowing, defi ned, 327COPYRIGHTEDbackdoor MATERIAL slider, 234, 328 All-Star, defi ned, 327 backhand plays, 178–179 All-Star Break, 327 backstops, 28, 329 All-Star Game, 252, 328 backup, 329 Alphonse and Gaston Act, 328 bad balls, 59, 329 aluminum bats, 19–20 bad bounces (bad hops), 272, 329 -

3 Fielder Drills by Position

3 FIELDER DRILLS BY POSITION 42 Chapter 3 3-1 PITCHER FIELDING DRILLS The pitcher is the fifth infielder covering the middle of the diamond. The highest percentage of batted balls go through the center of the diamond. Hitters are told when they fall behind in the count, shorten the bat and think "middle." If the hitters are thinking middle and are hitting that way, the pitcher must work hard at being that fifth infielder. It is scary to think that the pitcher is only 60 feet from the hitter, consequently, his reaction time to the batted ball has to be better than that of the third baseman. The third baseman's position is called the "hot corner," the pitcher's defensive position probably should be called "suicide alley." In pitching mechanics drills we placed a great deal of emphasis on the pitcher's glove hand and the finish position in the delivery of the ball. The glove hand must be in front and ready for the ball. If pitchers are careless and let their glove hands fly behind them, they are going to get seriously hurt somewhere along the way. Pitching absolutes are: • have good control • keep the runners on 1st base by having a great pick-off move • be an outstanding fielder • concentrate • concentrate some more These "absolutes" can be taught by emphasizing the following drills. P-1. DRILL: TWO MAN PEPPER Purpose: To continually play the ball off the bat. I believe that if it is played properly pepper is the best drill in baseball. Players and Equipment Needed: Two pitchers, gloves, a bat and several baseballs.