Immutability and Innateness Arguments About Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Book Spring 2007:Book Winter 2007.Qxd.Qxd

Anne Fausto-Sterling Frameworks of desire Genes versus choice. A quick and dirty tain unalienable Rights . ” Moreover, search of newspaper stories covering sci- rather than framing research projects in enti½c research on homosexuality shows terms of the whole of human desire, we that the popular press has settled on this neglect to examine one form, heterosex- analytic framework to explain homosex- uality, in favor of uncovering the causes uality: either genes cause homosexuality, of the ‘deviant’ other, homosexuality. or homosexuals choose their lifestyle.1 Intellectually, this is just the tip of the The mischief that follows such a for- iceberg. When we invoke formulae such mulation is broad-based and more than as oppositional rather than developmen- a little pernicious. Religious fundamen- tal, innate versus learned, genetic versus talists and gay activists alike use the chosen, early-onset versus adolescent genes-choice opposition to argue their experience, a gay gene versus a straight case either for or against full citizenship gene, hardwired versus flexible, nature for homosexuals. Biological research versus nurture, normal versus deviant, now arbitrates civil legal proceedings, the subtleties of human behavior disap- and the idea that moral status depends pear. on the state of our genes overrides the Linear though it is, even Kinsey’s scale historical and well-argued view that we has six gradations of sexual expression; are “endowed by [our] Creator with cer- and Kinsey understood the importance of the life cycle as a proper framework for analyzing human desire. Academics Anne Fausto-Sterling is professor of biology and –be they biologists, social scientists,2 or gender studies in the Department of Molecular cultural theorists–have become locked and Cell Biology and Biochemistry at Brown Uni- into an oppositional framework. -

Section 377 IPC ……………………….…………………………

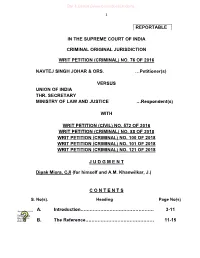

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) 1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 76 OF 2016 NAVTEJ SINGH JOHAR & ORS. …Petitioner(s) VERSUS UNION OF INDIA THR. SECRETARY MINISTRY OF LAW AND JUSTICE …Respondent(s) WITH WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 572 OF 2016 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 88 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 100 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 101 OF 2018 WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 121 OF 2018 J U D G M E N T Dipak Misra, CJI (for himself and A.M. Khanwilkar, J.) C O N T E N T S S. No(s). Heading Page No(s) A. Introduction………………………………………… 3-11 B. The Reference……………………………………… 11-15 Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) 2 C. Submissions on behalf of the petitioners…… 15-30 D. Submissions on behalf of the respondents and other intervenors.………………………….… 31-44 E. Decisions in Naz Foundation and Suresh Koushal………………..…………………………….. 45-48 F. Other judicial pronouncements on Section 377 IPC ……………………….………………………….. 48-57 G. The Constitution – an organic charter of progressive rights………………………………… 57-64 H. Transformative constitutionalism and the rights of LGBT community………………………. 65-74 I. Constitutional morality and Section 377 IPC…. 74-81 J. Perspective of human dignity…………………… 81-89 K. Sexual orientation…………………………………. 89-96 L. Privacy and its concomitant aspects…………... 96-111 M. Doctrine of progressive realization of rights…………………………………………………. 111-118 N. International perspective…………………………. 118 (i) United States……………………………… 118-122 (ii) Canada…………………………………….. 123-125 (iii) South Africa………………………………. 125 (iv) United Kingdom…………………………. 126-127 (v) Other Courts/Jurisdictions…………….. 127-129 Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) 3 O. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Practitioner, and Community Leader Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu to UH West Oʻahu for a Film Screening and a Series of Presentations This February

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Julie Funasaki Yuen, (808) 689-2604 Feb. 9, 2015 [email protected] Public Information Officer UH West Oʻahu Distinguished Visiting Scholar Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu to discuss Pacific Islander culture and transgender identity Free film screening of “Kumu Hina” Feb. 23 KAPOLEI --- The University of Hawai‘i – West O‘ahu welcomes Distinguished Visiting Scholar and Kanaka Maoli teacher, cultural practitioner, and community leader Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu to UH West Oʻahu for a film screening and a series of presentations this February. Wong-Kalu is a founding member and outreach specialist for Kulia Na Mamo, a community organization with a mission to improve the quality of life for māhū wahine (transgender women) and cultural director for Hālau Lōkahi public charter school. All events are free and open to the public, and sponsored by the UHWO Distinguished Visiting Scholars Program. The program brings seasoned scholars and practitioners in the humanities, social sciences, and indigenous arts, traditions and cultures to UH West Oʻahu for the benefit of students, faculty, staff and the community. “Kumu Hina” reception, film screening and discussion Monday, Feb. 23, 4-7 p.m. UH West Oʻahu, Campus Center Multi-purpose Room, C208 UH West Oʻahu will host a film screening of the documentary “Kumu Hina” followed by a discussion with Distinguished Visiting Scholar Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu and “Kuma Hina” Director/Producers Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer. “Kumu Hina” is told through the lens of Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, an extraordinary Native Hawaiian who is both a proud and confident māhū (transgender woman) and an honored and respected kumu (teacher) and community leader. -

Cynthia Nixon Ambassador, Susan G. Komen for the Cure®

Cynthia Nixon Ambassador, Susan G. Komen for the Cure® Emmy and Tony Award-winner Cynthia Nixon has been a critically acclaimed and sought-after actress since the age of twelve. And now she has joined Susan G. Komen for the Cure®, using her talents as an ambassador to help raise awareness and encourage others to join the breast cancer movement. Nixon was last in New Regency's feature Little Manhattan opposite Bradley Whitford as well as in Alex Steyermark's One Last Thing, which premiered at the 2005 Toronto Film Festival and was screened at the 2006 Tribeca Film Festival. The actress also starred in HBO's telepic Warm Springs, in which she plays Eleanor Roosevelt opposite Kenneth Branagh's Franklin Roosevelt. This role earned Nixon a Golden Globe nomination, a SAG Award nomination, and an Emmy nomination for Best Actress in a Miniseries or Movie Made for Television. In 2004 she starred in the mini-series Tanner on Tanner, directed by Robert Altman and written by Garry Trudeau. For six seasons Nixon appeared in HBO's much celebrated series, Sex and the City, in which she played Miranda, a role that garnered her an Emmy Award in 2004 for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series, two other Emmy nominations, and four consecutive Golden Globe nominations. Nixon was honored with the 2001 and 2004 SAG Award for Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Comedy Series. Nixon was last seen off-Broadway in the title role of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. In 2006 the actress completed a successful run in the Manhattan Theatre Club production of David Lindsay-Abair's Pulitzer Prize winning play Rabbit Hole for which she won a Tony Award as well as a Drama League nomination and an Outer Critics Circle Award. -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us. -

(917) 626-1300 Susan Lucci, Star Of

Contact: Paul Nugent at JGPR: [email protected] or (917) 626-1300 Susan Lucci, star of “Devious Maids,” Emmy® award-winner for “All My Children,” and former Women Who Care award honoree & Liza Huber, Founder & CEO of Sage Spoonfuls to Co-Host The 15th Annual UCP of NYC Women Who Care Awards Luncheon benefitting United Cerebral Palsy of New York City on Monday, May 9, 2016 Tamsen Fadal, Robin Givens, Donna Hanover, Ali Stroker & Paula Zahn to Co-Chair the Awards Luncheon NEW YORK, NEW YORK (January 25, 2016) – Edward R. Matthews, CEO of United Cerebral Palsy of New York City (UCP of NYC), and Loreen Arbus, Founder & Chair of Women Who Care, announced today that Susan Lucci, now in her fourth season as star of the hit series “Devious Maids,” Emmy® award-winning actress from “All My Children,” and New York Times best-selling author, will return for the fourth consecutive year as host of The 15th Annual Women Who Care Awards Luncheon. For the first time, Liza Huber, Founder & CEO of Sage Spoonfuls and past star of the hit TV series “Passions,” will co-host the awards luncheon with her mother Ms. Lucci, for the event taking place May 9th, the day after Mother's Day. This will mark the first time a mother and daughter team have co-hosted Women Who Care. Ms. Huber has a son, Brendan, with Cerebral Palsy, and was recently featured in People Magazine and on TV shows including “The Dr. Oz Show,” “The Meredith Vieira Show,” and “Entertainment Tonight” to help raise awareness for Cerebral Palsy and the work of UCP of NYC. -

A Correlational Study on the Neurodevelopemental

A CORRELATIONAL STUDY ON THE NEURODEVELOPEMENTAL THEORIES OF HUMAN SEXUALITY HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College By Keimche P. Wickham San Marcos, Texas May 2016 A CORRELATIONAL STUDY ON THE NEURODEVELOPMEMENTAL THEORIES OF HUMAN SEXUALITY by Keimche P. Wickham Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Natalie Ceballos, Ph.D. Department of Psychology Second Reader: __________________________________ Judith Easton, Ph.D. Department of Psychology Approved: ____________________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College TABLE OF CONTENTS . LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………vii LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………..…viii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………..….……….…...…viiii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………..…..…..…...1 History of Homosexuality ……......…………… ………..….….…2 Social and Psychological issues of Homosexuality...…..................4 Scientific Studies of Homosexuality.………………..………….... 5 Fraternal Birth Order Effect……………………………………….6 The Kin Selection Theory……………………………......………..7 II. METHOD…………………..………………………..…………..……8 Questionnaires………………....………….………………………9 Data Analysis ………………………………….…….…………..10 Birth Order……………………………….....….………………...11 Parent-Child Relationships………………………………..……..11 III. RESULTS……………………………………………………………12 Birth Order Effects……………......………………………….…..13 Parent-Child Relationships………......………………………......14 IV. DISCUSSION…………………………………………………….….16 Strengths and Limitations……………………………………..…19 -

Key Terms LGBTQ

KEY TERMS Sex (Sex Assigned at Birth): A biological construct that refers to our physical attributes and our genetic makeup. This includes determines birth-assigned male or female sex. Gender Identity: A person’s internal, deeply-felt sense of being male, female, something other, or in between. Gender identity is not determined by genitals or Sex Assigned at Birth Gender Expression: An individual’s characteristics and behaviors such as appearance, dress, mannerisms, speech patterns, and social interactions that are perceived as masculine or feminine. Gender Nonconformity (gender creative, gender expansive): Gender expressions that fall outside of societal expectations for one’s sex assigned at birth • May (or may not) impact gender identity: Natal male: “I am a girl and I like to express femininity.” Natal male: “I am a boy and I like to express femininity.” Non-Binary Gender: An umbrella term that reflects gender identities that don’t fit within the accepted binary of male and female. Individuals can feel they are both genders, neither or some mixture thereof. Terms under this umbrella: genderqueer, gender fluid, agender, bigender, etc. Non-binary folks may use they/them/theirs or other neutral pronouns. Gender diverse/fluid/expansive/creative: Conveys a wider, more flexible range of gender identity and/or expression. It reinforces the notion that gender is not binary, but a continuum; and that many children and adults express their gender in multiple ways. Sexual Orientation: The gender to which one is romantically and/or sexually attracted Transgender or Trans : Individuals with an affirmed gender identity different than their sex-assigned-at-birth. -

THE 71St ANNUAL TONY AWARDS LIVE and ONLY on Foxtel Arts, Monday, June 12 from 10Am AEST with a Special Encore Screening Monday June 12 at 8.30Pm AEST

Media Release: Monday June 5, 2017 THE 71st ANNUAL TONY AWARDS Stars from stage and screen join host Kevin Spacey LIVE AND ONLY ON FOXTEL ARTS NEXT MONDAY JUNE 12 AT 10AM Or stream it on Foxtel Play Foxtel Arts channel will broadcast Broadway’s ultimate night of nights the 71st Annual Tony® Awards live and exclusive from Radio City Music Hall in New York City on Monday June 12 from 10am. Marking 71 years of excellence on Broadway, The Tony Awards honour theatre professionals for distinguished achievement on Broadway and has been broadcast on CBS since 1978 and are presented by The Broadway League and the American Theatre Wing. For the first time, Tony and Academy Award winning actor Kevin Spacey will host the Tonys and will be joined by some of the biggest stars from theatre, television, film and music who will take to the stage at the 71st Annual Tony Awards. Broadway’s biggest night will feature appearances by Orlando Bloom, Stephen Colbert, Tina Fey, Josh Gad, Taraji P. Henson, Scarlett Johansson, Anna Kendrick, Keegan-Michael Key, Olivia Wilde, and 2017 Tony Nominees Josh Groban, Bette Midler and Ben Platt. Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812, an offbeat pop opera based on a slice of Tolstoy’s “War and Peace”, which stars Josh Groban leads with 12 nominations, including the category for Best Musical alongside Come From Away, about a Canadian town that sheltered travellers after the terrorist attacks of 2001, Dear Evan Hansen, about an anxiety-ridden adolescent who insinuates himself into the life of a grieving family and Groundhog Day The Musical, an adaptation of the Bill Murray Film. -

1 Introducing LGBTQ Psychology

1 Introducing LGBTQ psychology Overview * What is LGBTQ psychology and why study it? * The scientific study of sexuality and ‘gender ambiguity’ * The historical emergence of ‘gay affirmative’ psychology * Struggling for professional recognition and challenging heteronormativity in psychology What is LGBTQ psychology and why study it? For many people it is not immediately obvious what lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) psychology is (see the glossary for defini- tions of words in bold type). Is it a grouping for LGBTQ people working in psychology? Is it a branch of psychology about LGBTQ people? Although LGBTQ psychology is often assumed to be a support group for LGBTQ people working in psychology, it is in fact the latter: a branch of psychology concerned with the lives and experiences of LGBTQ people. Sometimes it is suggested that this area of psychology would be more accurately named the ‘psychology of sexuality’. Although LGBTQ psychology is concerned with sexuality, it has a much broader focus, examining many different aspects of the lives of LGBTQ people including prejudice and discrimination, parenting and families, and com- ing out and identity development. One question we’re often asked is ‘why do we need a separate branch of psychology for LGBTQ people?’ There are two main reasons for this: first, as we discuss in more detail below, until relatively recently most psychologists (and professionals in related disciplines such as psychiatry) supported the view that homosexuality was a mental illness. ‘Gay affirmative’ psychology, as this area was first known in the 1970s, developed to challenge this perspective and show that homosexuals are psychologically healthy, ‘normal’ individuals.