The New Palestinian Curriculum 2018–19 Update—Grades 1–12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

The Pouce Eit\Ltftion in Belsstine

, . / \ ! the pouce eit\ltftion In Belsstine Bescher Biuad of ths ~cret@xlat //I It coA%13t3 of a iTleadqua.rtsr8 (iA JerumlEB) aAd SIX police alstrlcte In cacc~8 with the admninestr8tivo dlviaio~ of the country. The dlstrfcts ~Of'tb pouch e&Q the fol&owlng: J+wuss~, udd.a (E.Q.Jaffa), Glfa, &z&r, Gazmr~~(R,Q.lBIeLblus), Oallle% (Hd.Q.&zts~etb). The p&sonael serving et 3kidq&~sre it3 app3mx3mately 400-500. Of th8sei about fifty per cent are polohe persayl, the other fifty per cent nuomb& Of pt3rSOaXre~ fo a dbtrict 8.Q. 1% 100-150, of w$ich tie prOpO~lOn of poll08 p8re~nxselconp3di wilt23 eiv%liasle is 75-25. Of the police personnel eerv~ at police X.Q.,md dietrict ltP.Q.'e, aza.the average about fifty per cent ar% BzWileh, tvmty-flv% par cent Arab, adi twmty-five per cent Jwieh, c ~ccordAx@'to whether the axxm of the distrfct lra premtily Arab ok Jewlah. IA moth mixed area8 Arexbe.and Jews work to@iber. * The'Dletrlct H.Q& have urider thels c- police divielcms, of which ' there are between two &l oev$rn in each dktrlct, The dlvlelone qaln have md5r their cm a number of police stat;o~s, police paste, frontier control poets and coast guard atatfom, varying In nur&sr in the different dletrlctf3 fro& about YXtea3;n to thlrty . The totd&b%P of poUc% personza%3.,~nPaX%etin% b&s varied coxmlderably I during the period of the kindate, according to the general security eltuatlon IA the OOuAtry. -

F-Dyd Programme

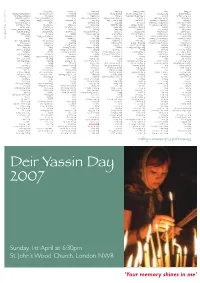

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

Palestine Village Statistics

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION' COMMISSION FOR PAIESTINE RES TR IC TED Com,Tech/7/Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX B NON - JEWISH POPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARIES HBLD BY THE ISRAEL DEFENCE ARMY ON Urn IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SubfMARY * a . * . * . a. , , . 1 ACRESUBDISTRICT ft . l ft. (I 2-3 SAFAD 11 *wb*a*.e+4u 4-6 T IBER IAS I I .a7 NAZARETH 11 *a**ea+*aaq 8 BE ISAN I I a 9-10 HA IPA I I . v. 11-12 JENIN tt 13 TULKAREM t I aaaa14 JAFFA II .a~I? RAMIE ~t , 16-18 JERUSALEM It 19-20 HEBRON t1 21 GAZA ~t baua22-23 BEERSHEBA .24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH POPULATION Within the boundaries held by the Israel Defence Army . on 1.5.49 AS ON 1.4.45 In accordance with the Palestine Government Village * Statistics, April 1945. S UB DISTRICT MOS LEMS CHRIS TIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11 ,150 6,940 65,380 ' . SAFAD W-t, 510 19630 780 46,920 TIBER IAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 l19@t0 W 38,500 BE ISAN 15,920 650 20 16 590 HA IFA 83,590 30,200 4,330 120,120 JENIN 89390 60 m 8,450 TULKAREM 22,310 10 22,320' JAFFA 93 9 070 16,300 330 109,700 RAMLE 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 M 47,740 HEBR ON 19,810 10 ..R 19,820 GAZA 69,230 l60 69,390 TOTAL 621,030 92 060 13 710 726,800 NON - JEWISH POPULATION ACRE SUB - DISTRICT VILLAGE M OS LEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ABU S INAN ACRE AMQA ARRABA BASSA BEIT JANN & EIN EL ASAD B INA B IRWA BUQEIA DAMUN DEIR EL ASSAD DEIR EL HATO. -

Page 219-248

HOLY SITES INDEX Page/ Page/ Page/ Page/ Page/ Name Grid Name Grid Name Grid Name Grid Name Grid Esh Sh. el Qureishi 21 C3 Sh. Saleem Abu Sh. Shu'eib 117 A3 Sh. Wushah 33 A2 Sitt esh Shamiya 106 C1 Qusatin 127 B2 Mussalem 132 B2 Shukr 22 B2 Yahya 34 B3 Sitt Fattouma 87 B2 el Qutati 132 A2 Saleh Cem 15 C3 Shukr 26 C3 el Yamani 89 B2 Haniya 97 A2 Qutteina 50 C1 Salem 156 B1 Siddiq 18 A3 Ya'qub 86 B1 Laila 48 A2 Rabi' 40 C2 Salem 156 B1 Siddiq 31 A1 Ya'qub 118 B1 Mariam 65 B3 Rabi' 23 B1 es Salhi 117 B1 es Sidrah 104 A1 Yasin 105 A1 Mariam 79 A2 Rabia 25 B2 Salih 31 C1 es Siri 71 B2 Yasin 109 A1 el Mella 26 A1 Radgha 60 B1 Salih 55 C1 Smad 53 C2 Yasin 96 C3 Mona 97 A2 Radhi 37 B1 Salih 64 A3 Subeih 40 B1 Yihya 20 C3 Mu'mina 88 B1 Radwan 132 A2 Salih 64 B3 Subh 80 A3 Yusuf 86 B3 Nasa 18 B3 Radwan 133 C2 Salih 83 B2 Subh 80 A3 Yusuf 88 B3 Nasa 80 A1 Radwan 56 B1 Salih 87 B3 Suleiman 14 B3 Yusuf 95 B2 Nasa 90 A2 Radwan 87 B1 Salih 87 C3 Suleiman 97 A2 Yusuf 14 A2 Najla 116 C3 er Rafa'i 88 B1 Salih 96 B2 Suleiman 42 A1 Yusuf 86 A3 Qadria 17 A3 Rahhal 88 C1 Salih 98 C3 Suleiman 157 B2 Yusuf 88 C3 Qadria 18 C3 Rakein 65 C1 Salih 105 B3 Suleiman el Yusuf 96 C1 Qamra 87 B2 Ramadan 97 C3 Salih 137 C1 Farsi 105 C2 Yusuf 96 B3 Sakeena 30 B2 Ramadan 23 C3 Salih 15 C3 Suleiyib 155 B1 Yusuf 116 C3 Sara 25 B1 Rashid 144 C1 Salih 51 C2 Suliyman 98 B2 Yusuf & Isma'il 17 A3 Shamsa 26 C1 Raslan 29 A2 Salih 52 A1 Suliyman 107 B3 Yusuf el 'Ateiq 88 B2 Sidrat esh er Rifai 78 C2 Salih 55 A2 Suliyman 120 A2 Yusuf el Shuyukh 21 B3 Rihab 53 C3 Salih 57 A1 Sultan Badr 106 A2 Barbarawi 121 C3 Skuna - Sakina 33 A1 Rihan 49 A1 Salih 86 A3 Sumeit 70 C1 Sh. -

Meet Handala

Welcome. Meet Handala Handala is the most famous of Palestinian political cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s characters. Depicted as a ten- year old boy, he first appeared in 1969. In 1973, he turned his back to the viewer and clasped his hands behind his back. The artist explained that the ten-year old Handala represented his age when he was forced to leave Palestine and would not grow up until he could return to his homeland; his turned back and clasped hands symbolised the character’s rejection of “outside solutions.” He wears ragged clothes and is barefoot, symbolising his allegiance to the poor. Handala remains an iconic symbol of Palestinian identity and defiance. Let him share his story with you. This series of educational panels is offered as an introduction to a deeper understanding of both the history and present realities of the Palestinian struggle for justice. We believe that the facts have been largely presented in a biased and misleading way in the mainstream media, leaving many people with an incomplete and often incorrect understanding of the situation. Please take a few minutes to stroll through our exhibit. Please open your hearts and minds to a larger picture of the conflict. Zionism: the root of the Israeli - Palestinian conflict. Zionism, in its political manifestation, is committed to the belief that it is a good idea to establish, in the country of Palestine, a sovereign Jewish state that attempts to guarantee, both in law and practice, a demographic majority of ethnic Jews in the territories under its control. Political Zionism claims to offer the only solution to the supposedly intractable problem of anti-Semitism: The segregation of Jews outside the body of non-Jewish society. -

![The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9550/the-birth-of-the-palestinian-refugee-problem-revisited-2nd-edition-6959550.webp)

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]

THE BIRTH OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM REVISITED Benny Morris’ The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, was first published in 1988. Its startling reve- lations about how and why 700,000 Palestinians left their homes and became refugees during the Arab–Israeli war in 1948 undermined the conflicting Zionist and Arab interpreta- tions; the former suggesting that the Palestinians had left voluntarily, and the latter that this was a planned expulsion. The book subsequently became a classic in the field of Middle East history. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited represents a thoroughly revised edition of the earlier work, compiled on the basis of newly opened Israeli military archives and intelligence documentation. While the focus of the book remains the 1948 war and the analysis of the Palestinian exodus, the new material con- tains more information about what actually happened in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, and how events there eventually led to the collapse of Palestinian urban society. It also sheds light on the battles, expulsions and atrocities that resulted in the disintegration of the rural communities. The story is a harrowing one. The refugees now number some four million and their existence remains one of the major obstacles to peace in the Middle East. Benny Morris is Professor of History in the Middle East Studies Department, Ben-Gurion University.He is an outspo- ken commentator on the Arab–Israeli conflict, and is one of Israel’s premier revisionist historians. His publications include Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist–Arab Conflict, 1881–2001 (2001), and Israel’s Border Wars, 1949–56 (1997). -

List of 418 Villages

The 418 Destroyed Villages of Palestine during Nakba District of Acre — 26 villages District of Bisan — Cont'd 1 Amqa 36 al-Hamidiyya 2 Arab al-Samniyya 37 al-Hamra 3 al-Bassa 38 Jabbul 4 al-Birwa 39 Kafra 5 al-Damun 40 Kawkab al-Hawa 6 Dayr al-Qasi 41 Arab al-Khunayzir 7 al-Gabisiyya 42 Masil al-Jizl 8 Iqrit 43 al-Murassas 9 Khirbat Iribbin 44 Qumya 10 Khirbat Jiddin 45 al-Sakhina 11 al-Kabri 46 al-Samiriyya 12 Kufr Inan 47 Sirin 13 Kuwaykat 48 Tall al-Shawk 14 al-Manshiyya 15 al-Mansura 49 Khirbat al-Taqa 16 Miar 50 al-Tira 17 al-Nabi Rubin 51 Umm ‘Ajra 18 al-Nahr 52 Umm Sabuna 19 al-Ruways 53 Yubla 20 Suhmata 54 Zab’a 21 al-Sumayriyya 55 Khirbat al-Zawiya. 22 Suruh 23 al-Tall District of Beersheba — 3 villages 24 Tarbikha 56 Al-’Imara 25 Umm al-Faraj 57 al-Jammama 26 al-Zib 58 al-Khalasa District of Bisan — 29 villages District of Gaza — 45 villages 27 Arab al-’Arida 59 Arab Suqrir 28 Arab al-Bawati 60 Barbara 29 Arab al-Safa 61 Barqa 30 al-Ashrafiyya 62 al-Batani al-Gharbi 31 al-Birra 63 al-Batani al-Sharqi 32 Danna 64 Bayt ‘Affa 33 Farwana 65 Bayt Daras 34 al-Fatur 66 Bayt Jirja 35 al-Ghazzawiyya 67 Bayt Tima Source: "All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948", Ed. Walid Khalidi, 1991. The 418 Destroyed Villages of Palestine during Nakba District of Gaza — Cont'd District of Haifa — 51 villages 68 Bi’lin 69 Burayr 105 Abu Zurayq 70 Dayr Sunayd 106 Arab al-Fuqara’ 71 Dimra 107 Arab al-Nufay’at 72 al-Faluja 108 Arab Dhahrat al-Dhumayri 73 Hamama 109 Atlit 74 Hatta 110 Ayn Ghazal 75 Hiribya -

Petitions Sent from Palestine to Istanbul from the 1870'S Onwards

Yuval BEN-BASSAT 89 IN SEARCH OF JUSTICE∞: Petitions sent from Palestine to Istanbul from the 1870’s Onwards “∞The rich people in our village have become utterly poor and they need alms, and for the same reason some of the people of the village have even had to leave their original place of birth and flee to other lands.∞” The villagers of Sarafand al-Kubra in a petition to the Grand-Vizier in 1879 M uch of the fast growing body of studies dealing with the history of Palestine at the end of the 19th century focuses either on the political and ideological aspects pertaining to the early Arab — proto-Zionist encoun- ters,1 including the Jewish immigration and colonization activity,2 or the Department of Middle Eastern History, University of Haifa [email protected] 1 To cite only a few of the main works dealing political-ideological issues, see Neville J. MANDEL, The Arabs and Zionism before World War I (Berkeley∞: University of Califor- nia Press, 1976)∞; Kemal KARPAT, “∞Ottoman Immigration Policies and Settlement in Pal- estine,∞” in Abu-Lughod, Ibrahim and Baha Abu-Laban (eds.), Settler Regimes in Africa and the Arab World∞: The Illusion of Endurance (Wilmette∞: Medina University Press International, 1974), p. 57-72∞; Mim Kemal ÖKE, “∞The Ottoman Empire, Zionism and the Question of Palestine (1880-1908),∞” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 14 (1982), p. 329-341∞; Yosef GORNY, Zionism and the Arabs, 1882-1948∞: a Study of Ideology (Oxford∞: Clarendon Press, 1987)∞; Anita SHAPIRA, Land and Power∞: The Zionist Resort to Force, 1881-1948 (New-York∞: Oxford University Press, 1992). -

In Israel, Are Ignorant of the Foundations of the Israeli State

Countdown to Catastrophe Palestine 1948 a daily chronology Hugh Humphries in collaboration with Ross Campbell Published by Scottish Friends of Palestine Copyright: Hugh Humphries and Ross Campbell Published in 2000 by Scottish Friends of Palestine 2000 "no settlement can be just and complete if recognition is not accorded to the right of the Arab refugee to return to the home from which he was dislodged by the hazards and strategy of the armed conflict between Arabs and Jews in Palestine. It would be an offence against the principles of elemental justice if these innocent victims of the conflict were denied the right to return to their homes while Jewish immigrants flow into Palestine, and, indeed, at least offer the threat of permanent replacement of the Arab refugees who have been rooted in the land for centuries." Count Folke Bernadotte,UN Special Mediator to Palestine Progress Report,GAOR,3rd Sess., Supp No.11 at 14, UN Doc A/648 (1948) acknowledgement This book could not have been published without assistance from the The League of Arab States, London Mission. Scottish Friends of Palestine acknowledge this assistance and express their gratitude. ISBN 0 9521210 2 6 This chronology, and the detail contained therein, would not have been possible without the able assistance of my collaborator, Ross Campbell. It was Ross who trawled the pages of the many volumes of books and journals, cross-referencing the events with the dates. No detail was too small, if it could be chronologically identified. I am indebted to his enthusiasm and patience. Any errors or opinion expressed are my responsibility.