CAROL KAYE by P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sugar Shoppe the Sugar Shoppe Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Sugar Shoppe The Sugar Shoppe mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: The Sugar Shoppe Country: UK Released: 2013 Style: Easy Listening, Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1914 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1871 mb WMA version RAR size: 1786 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 264 Other Formats: ADX MMF MP4 ASF AU MPC VQF Tracklist Hide Credits The Original Album Skip-a-long Sam 1 3:00 Written-By – Donovan Leitch* The Attitude 2 2:18 Written-By – Peter Mann Baby Baby 3 3:18 Written-By – Helen Lewis, Kay Lewis Take Me Away 4 2:59 Written-By – Jackie Trent, Tony Hatch Let The Truth Come Out 5 2:57 Written-By – Peter Mann Follow Me (From "Camelot") 6 2:30 Written-By – F. Loewe - A.J. Lerne* Poor Papa 7 2:24 Written-By – Billy Rose, Harry Woods Privilege (From The Film "Privilege") 8 3:08 Written-By – Michael Leander* Papa, Won't You Let Me Go To Town With You 9 3:30 Written-By – Bobbie Gentry The Candy Children Song 10 2:35 Written-By – L. Hood*, P. Mann*, V. Garber* Hangin' Together 11 2:29 Written-By – L. Hood*, P. Mann*, V. Garber* The Bonus Tracks Skip A Long Sam (Mono 45) 12 3:02 Written-By – Donovan Leitch* Let The Truth Come Out (Mono 45) 13 2:59 Written-By – Peter Mann Privilege (From The Film "Privilege") (Mono 45) 14 3:12 Written-By – Michael Leander* Poor Papa (Mono 45) 15 2:26 Written-By – Billy Rose, Harry Woods Save The Country (Acetate) 16 3:04 Written-By – Laura Nyro Easy To Be Hard (Acetate) 17 3:51 Written-By – G. -

Good Vibrations Sessions. from Came Our Way on Cassette from California, and We “Unsurpassed Masters Vol

Disc 2 231. George Fell Into His French Horn 201. Good Vibrations Sessions The longest version yet heard, and in stereo. This Tracks 1 through 28 - Good Vibrations Sessions. From came our way on cassette from California, and we “Unsurpassed Masters Vol. 15”, but presenting only the last, digitally de-hissed it. best and most complete attempt at each segment. 232. Vegetables (Alternate lyric and arrangement) Track 202. Good Vibrations Sessions Another track from the California cassettes. This Track 203. Good Vibrations Sessions version has significant lyric and arrangement Track 204. Good Vibrations Sessions differences. Track 205. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 206. Good Vibrations Sessions 233. Surf’s Up Sessions Track 207. Good Vibrations Sessions While not full fidelity, this has the best sound yet, Track 208. Good Vibrations Sessions and a bit of humorous dialogue between Brian Track 209. Good Vibrations Sessions Wilson and session bassist Carol Kaye. From the Track 210. Good Vibrations Sessions California cassetes, and now digitally de-hissed. Track 211. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 212. Good Vibrations Sessions 234. Wonderful Track 213. Good Vibrations Sessions Beach Boys incomplete vocal attempt. Track 214. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 215. Good Vibrations Sessions 235. Child is Father to The Man Track 216. Good Vibrations Sessions Beach Boys incomplete vocal attempt. Tracks 234 Track 217. Good Vibrations Sessions and 235 are from the Japanese “T-2580” “Smile” Track 218. Good Vibrations Sessions bootleg and now digitally de-hissed. Track 219. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 220. Good Vibrations Sessions 236. Heroes & Villains Part Two (Original mono Track 221. Good Vibrations Sessions mix) Track 222. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

Newsletternewsletter March 2015

NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER MARCH 2015 HOWARD ALDEN DIGITAL RELEASES NOT CURRENTLY AVAILABLE ON CD PCD-7053-DR PCD-7155-DR PCD-7025-DR BILL WATROUS BILL WATROUS DON FRIEDMAN CORONARY TROMBOSSA! ROARING BACK INTO JAZZ DANCING NEW YORK ACD-345-DR BCD-121-DR BCD-102-DR CASSANDRA WILSON ARMAND HUG & HIS JOHNNY WIGGS MOONGLOW NEW ORLEANS DIXIELANDERS PCD-7159-DR ACD-346-DR DANNY STILES & BILL WATROUS CLIFFF “UKELELE IKE” EDWARDS IN TANDEM INTO THE ’80s HOME ON THE RANGE AVAilable ON AMAZON, iTUNES, SPOTIFY... GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 Decatur Street New Orleans, LA 70116 phone: (504) 525-5000 fax: (504) 525-1776 email: [email protected] website: jazzology.com office manager: Lars Edegran assistant: Jamie Wight office hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm entrance: 61 French Market Place newsletter editor: Paige VanVorst contributors: Jon Pult and Trevor Richards HOW TO ORDER Costs – U.S. and Foreign MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter. Also you will be able to buy our products at a discounted price – CDs for $13.00, DVDs $24.95 and books $34.95. Membership continues as long as you order one selection per year. NON-MEMBERS For non-members our prices are – CDs $15.98, DVDs $29.95 and books $39.95. MAILING AND POSTAGE CHARGES DOMESTIC There is a flat rate of $3.00 regardless of the number of items ordered. -

Group: Northwest + 1 Album Title: Minor Suggestions

Group: Northwest + 1 Album Title: Minor Suggestions Personnel Damani (duh-mah-nee) Phillips – Alto Sax Kevin Woods – Trumpet Danny McCollim – Piano John Hamar (hay-mur)– Bass Julian MacDonough - drums Tracks Track Name Track Time Composer PublishinG credit 1. Minor Suggestions 5:43 Kevin Woods SpooM Music (BMI) 2. Clarity 6:26 Jon Hamar Jon Hamar 3. Flotsam and Jetsam 8:13 Kevin Woods SpooM Music (BMI) 4. Sunset’s Last Embrace 8:19 Damani Phillips Damani Phillips Music 5. Lisa 6:22 Victor Feldman/Zito Good Vibes Music 6. Curly 6:42 Jon Hamar Jon Hamar 7. Jump Off Joe 7:47 Jon Hamar Jon Hamar 8. Blues for Mingus 10:52 Danny McCollim 9. BiG Bird 5:37 Kevin Woods SpooM Music (BMI) Album Description It’s funny how 5 stranGers can be brouGht toGether to make music, and unexpectedly find a musical chemistry worth its weiGht in Gold. Our journey toGether beGan as a routine Guest artist appearance at Spokane Falls Community ColleGe in June of 2013, where trumpeter Kevin Woods assembled this Group as part of his Guest artist series. AlonG with his SFCC colleaGue Danny McCollum, Woods assembled an all-star rhythm section of WashinGton’s finest in invitinG Jon Hamar and Julian MacDonouGh to fill out the guest artist Group. Saxophonist Damani Phillips was invited to round out the Group’s horn section. Each of these musicians is active in performance and education, so guest artist invitations of this nature are a fairly common thinG. What was not so common, however, was the natural musical chemistry that the Group felt almost immediately; producing a concert of siGnificant gravity for both musicians and listeners alike. -

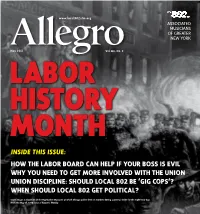

Inside This Issue

www.local802afm.org associated musicians of greater new York AllegroMay 2011 Vol 111, No. 5 labor history month INSIDE THIS ISSUE: how the labor board can help if your boss is evil why you need to get more involved with the union union discipline: should local 802 be ‘gig cops’? when should local 802 get political? Cover image: A depiction of the Haymarket Massacre at which Chicago police fired on workers during a general strike for the eight-hour day. From the May 15, 1886 issue of Harper’s Weekly. n news & views labor History Month calendar LOCal 802 For a complete, downloadable calendar, see www.NewYorkLaborHistory.org oFFiCers UNioN reps ANd orgANizers BeNeFit CoNCert FeAtUriNg pete seeger tino gagliardi, President Claudia Copeland (Theatre) Fri., May 13, 8 p.M. Jay Blumenthal, Bob Cranshaw (Jazz consultant) pete Seeger, peter yarrow, Brooklyn Women’s Chorus, Elise Financial Vice President Bryant, Judy Gorman, Bev Grant & the Dissident Daugh- John o’Connor, Recording Vice President Karen Fisher (Concert) ters, Dave Lippman, George Mann, & the NyC Labor Marisa Friedman (Theatre, Teaching artists) Chorus will perform to raise money for labor singer anne exeCUtiVe BoArd Shane Gasteyer (Organizing) Feeney who is battling small-cell lung cancer. Martin Bud Burridge, Bettina Covo, Patricia Luther King, Jr. Labor Center auditorium, 310 West 43rd Bob Pawlo (Electronic media) Dougherty, Martha Hyde, Gail Kruvand, Street, NyC 10036. $25 suggested minimum (purchase Richard Schilio (Club dates, Hotels) tickets online through paypal at www.annefeeney.com) Tom Olcott, Maxine Roach, Andy David Sheldon (Electronic media) Schwartz, Clint Sharman lABor History BoAt toUrs! Peter Voccola (Long Island) Boat tour of Brooklyn triAl BoArd Todd Weeks (Jazz) TuES. -

Neuzugänge Lieber Kunde, Diese Nachfolgende Liste Haben Wir Neu

Sonderposten https://www.deepgroove-schallplatten.de/web/de/sonderposten.afp Neuzugänge Lieber Kunde, diese nachfolgende Liste haben wir neu hereinbekommen. Bitte beachten Sie, diese Liste ist nicht in unserem Shopsystem integriert! Bestelllungen bitte per E-Mail, Telefon oder per Post. Labelbeschreibung und Abkürzungsverzeichnis Nummer: Interpret: Titel: Preis (€): 0 -More chords- 1969 w/ Woode,Clare. MPS 15032 (17) F M-/M- N0108 Buckner, Milt 19 ST; GLANZ-FOC -More chords- 1969 w/ Woode,Clare. MPS 15 237ST (47/V) D N0110 Buckner, Milt 26 VG++/M- ST; GLANZ-FOC N0111 Buckner, Milt Trio -Locked hands- MPS 15 199ST (47/V) D M--/M-- ST; GLANZ-FOC 20 -Play chords- 1966 w/Woode,Joe Jones. pink Saba SB 15 110ST N0112 Buckner, Milt Trio 16 M--/M-- ST; GLANZ-FOC -Play chords- 1966 w/Woode,Joe Jones. Saba SB 15 110ST (89/V) N0113 Buckner, Milt Trio 29 Erstausgabe mit Tannenbaum, M--/M-- ST; GLANZ-FOC -For all we know/Recorded live at Basin Street West,S.F.- 1971 N0116 Byrd, Charlie 20 w/Airto Moreira,etc. Columbia G 30622 (165) DOLP US M-/M- ST -The guitar artistry of- w/Keter Betts,Buddy Deppenschmidt. N0117 Byrd, Charlie 35 Riverside OLP 3007 (115/V) Mono NL VG++/M-; GLANZ -Guitars- rec.1975 w/Mariano, van´t Hof a.o. Atlantic 50193 D N0125 Catherine, Philip 16 M--/M-- ST -Live at the Berlin Philharmonie, with J.A.Rettenbacher, Intercord N0132 Cicero, Eugen 20 28779-7/1-2, DoLP, DE M-/VG++ -Klavierspielereien- w/Witte,Antolini. MPS 12 005ST (47/V/transition N0133 Cicero, Eugen 28 lbl.) D M--/M- ST; GLANZ -Klavierspielereien- w/Witte,Antolini. -

The Complete Eddie Cochran

Stand: 25.09.2021 The Complete Eddie Cochran 2 © Uli Kisker 2021 Red passages: I'm not 1000% sure if Eddie is on this! Blue passages: Concerts, radio-, tv-performances Green passages: test pressing First Release Digitally Re-Release 1953 - 1955 Summer 1953 to 1954 Chuck Foreman - Eddie Cochran Chuck Foreman's house - Bellflower, Los Angeles, California ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Rockin' It Instrumental 1:46 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Gambler's Guitar Eddie Cochran 2:37 STAMPEDE SPRCD 5002 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Jammin' With Jimmy Instrumental 1:42 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Tenderly Instrumental 2:48 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Steelin' The Blues Eddie Cochran 2:06 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Two Of A Kind Instrumental 1:51 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Two Of A Kind (backing track) Instrumental 1:37 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Stardust Instrumental 2:24 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Stardust (backing track) Instrumental 1:12 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Candy Kisses Eddie Cochran 1:43 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Chuck & Eddie's Boogie Instrumental 2:40 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 In The Mood Instrumental 1:16 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 I'll See You In My Dreams Instrumental 1:09 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Hearts Of Stone Eddie Cochran 1:51 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Water Baby Blues (short riff) Instrumental 0:41 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Humourous conversation Eddie Cochran & Chuck Foreman 1:03 ROCKSTAR RSRCD 011 Musicians - Eddie Cochran: vocal and guitar - Chuck Foreman: vocal and steel guitar. -

By Ro6 Bowman

SteveS I D E M E N H Douglas By Ro6 Bowman — lthough f e w f a n s k n e w s t e v e d o u g l a s b y After Douglas left Eddy in i960, he became an in- name, the sound of his muscular, R&B- demand session player on a cornucopia of R&B, rock inflected baritone and tenor sax playing and pop sessions. Douglas also led a band that includ was an essential ingredient of innumerable ed Spector as lead vocalist and guitarist. The band Alate-Fifties and early-Sixties hits, including the Ven broke up when Spector headed to New York in 1961. tures’ “Walk - Don’t Run,” Bob & Earl’s “Harlem Shuf W ithin a year, Spector had started Philles Records and fle,” the Crystals’ “He’s a Rebel,” the Beach Boys’ “Shut was flying Douglas to the East Coast to overdub his Down” and Jan & Dean’s “The Little Old Lady (From earthy sax tones on the earliest Crystals recordings. Pasadena).” In fact, virtually every sax solo on a rock W hen Spector elected to move Philles to Los Angeles, record emanating from Los Angeles in the first half of he tapped Douglas to put together a session band that the 1960s was played b y Steve Douglas, and every sub included Hal Blaine, pianists Leon Russell and Don sequent saxophonist in rock history, from Denny Pay- Randi, bassist Ray Pohlman (replaced by Carol Kaye ton of the Dave Clark Five to Clarence Clemons o f the after his death) and guitarists Glen Campbell, E Street Band, owes a significant debt to Douglas’s pal Howard Roberts and Tommy Tedesco. -

Our Best to You Capitol Star Line (S)T-1801 Various Artists Released November, 1962

Capitol Albums, 1801 to 1900 Our Best to You Capitol Star Line (S)T-1801 Various Artists Released November, 1962. Gold label Hits of Ella Mae Morse & Freddie Slack Capitol Star Line T-1802 Ella Mae Morse and Freddie Slack Released November, 1962. Gold label The All-Time Hits of Red Nichols Capitol Star Line (S)T-1803 Red Nichols and the Five Pennies Released November, 1962. Gold label An Evening with Romberg Capitol (S)W-1804 Carmen Dragon (Hollywood Bowl Pops Orchestra) Released November, 1962. An Evening with Cole Porter Capitol (S)W-1805 Carmen Dragon (Hollywood Bowl Pops Orchestra) Released November, 1962. The Soul of Country and Western Strings Capitol (S)T-1806 Billy Liebert Released November, 1962. Clair de Lune Capitol (S)W-1807 Stokowski, Pennario, Leinsdorf, Almeida, Dragon Released November, 1962. Capitol released this album in conjunction with a hardback book from Random House. Surfin’ Safari Capitol (D)T-1808 The Beach Boys Released October, 1962. Some early and later copies of this LP have a stereo front slick, although the LP is in Duophonic and the back slicks clearly state so. The New Frontier Capitol (S)T-1809 The Kingston Trio Released November, 1962. Big Bluegrass Special Capitol (S)T-1810 The Green River Boys & Glen Campbell Released November, 1962. My Baby Loves to Swing Capitol (S)T-1811 Vic Damone Released December, 1962. Themes of the Great Bands Capitol (S)T-1812 Glen Gray and the Casa Loma Orchestra Released January, 1963. Sounds of the Great Bands, Vol. 6 Memories Are Made of These Capitol (S)T-1813 George Chakiris Released December, 1962. -

An Investigation of the Electric Bass Guitar in Twentieth Century Popular Music and Jazz

An investigation of the electric bass guitar in Twentieth Century popular music and jazz. A thesis presented by David Stratton in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree, Master of Arts (Honours). School of Contemporary Arts College of Arts, Education, and Social Sciences University of Western Sydney April 2005 i Abstract The acoustic bass played mostly an accompanying role in popular music during the first half of the Twentieth Century, whereas the arrival of the electric bass guitar in the early 1950s presented new opportunities for acoustic bassists and musicians, composers, producers, engineers, the recording industry and the listening public. The distinctive sound of the electric bass guitar encouraged musicians to explore new timbres. The musicians who embraced the electric bass guitar developed its language, discovering and employing different techniques. The instrument became a catalyst for change and took on a more prominent role, forever changing the sonic landscape of popular music and jazz in the Twentieth Century. ii Acknowledgements I am indebted to the following people for their assistance during the period of my candidature: For technical support I thank Karl Lindbom, Paul Tilley, Clive Lendich, Benjamin Huie, Gary Fredericks and Brendan Read. The musicians who performed with me - Michael Bartolomei, Graham Jesse, Andrew Gander, Craig Naughton, Gordon Rytmeister, Nicholas McBride, Paul Panichi and Matthew Doyle. Kerrie Lester and Nikki Mortimer for granting permission to reproduce the paintings and etching. The musicians with whom I discussed my project, including Herbie Flowers, Carol Kaye, Max Bennett, Steve Hunter, Cameron Undy, Bruce Cale and Sandy Evans who have willingly encouraged me to quote.