Bartók's Orbit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Passacaglia and Lament in Ligeti's Recent Music

tijdschrift 2004 #9/1/2 22-01-2004 09:16 Pagina 1 stephen taylor Passacaglia and lament in Ligeti’s recent music1 György Ligeti’s music since his opera Le Grand Macabre (1974-77, revised 1996) could be described as a collage of different compositional techniques. Two of the most prominent are passacaglia, and a melodic figure Ligeti calls the ‘lament motive’, based on the descending chromatic scale. Passacaglia and chromatic scales have appeared in Ligeti’s music since his student days, but they have become especially prominent in his recent music. This essay examines the development of these two techniques, focusing on their combination in the Horn Trio and Violin Concerto. These works not only show us how Ligeti uses the same ideas in different contexts; they also provide an overview of his recent compositional technique. Of the various compositional devices that appear in Ligeti’s music since his opera Le Grand Macabre (1974-77), two of the most prominent are the passacaglia and a melodic figure Ligeti calls the ‘lament motive’, based on the descending chromatic scale. Table 1 shows a list of works from the opera to the late 1990s in which these techniques appear. This essay examines the two slow movements that combine them: the fourth movement of the Horn Trio, ‘Lamento’, from 1982, and the fourth move- ment of the Violin Concerto, ‘Passacaglia: Lento intenso’, written a decade later. While both movements have much in common, their differences also highlight how Ligeti’s music has developed since he embarked on his new style in the early 1980s. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

20 June 2021

20 June 2021 12:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918), Maurice Ravel (orchestrator) Tarantelle styrienne Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, Kazuhiro Koizumi (conductor) CACBC 12:07 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Keyboard Sonata in B flat major, Hob.16.41 Marc-Andre Hamelin (piano) PLPR 12:18 AM Grazyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) Suite for chamber orchestra (1946) Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jan Krenz (conductor) PLPR 12:26 AM Giovanni Valentini (1582/3-1649) Fra bianchi giglie, a 7 La Capella Ducale, Musica Fiata Koln DEWDR 12:35 AM Armas Jarnefelt (1869-1968) Korsholma - Symphonic Poem Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Ulf Soderblom (conductor) FIYLE 12:52 AM Marin Marais (1656-1728) Caprice ou Sonate (from Pieces de Viole, 4e Livre, Paris 1717) Pierre Pitzl (viola da gamba), Marcy Jean Brenner (viola da gamba), Augusta Campagne (harpsichord) ATORF 12:58 AM John Ireland (1879-1962) A Downland Suite Hannaford Street Silver Band, Bramwell Tovey (conductor) CACBC 01:15 AM Charles Avison (1709-1770) Concerto Grosso No.2 in G major for strings and continuo Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon (director) CACBC 01:29 AM Johan Halvorsen (1864-1935) Symphony No 2 in D minor, Op 67 Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Thomas Sondergard (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Concerto in D major for 3 trumpets and timpani, TWV.54:D4 Stefan Schultz (trumpet), Alexander Mayr (trumpet), Jorn Schulze (trumpet), NDR Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Riccardo Minasi (conductor) DENDR 02:09 AM Giles Farnaby (c. 1563 - 1640), Elgar Howarth (arranger) Fancies, -

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List FLUTE

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List Please submit additional repertoire, including concertante pieces, to both Dr. Andrizzi and to your respective Department Head for consideration before the application deadline. FLUTE Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto for flute and strings, Op. 45 strings Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto No 2, Op. 111 orchestra Bach, Johann Sebastian: Suite in B Minor BWV1067, Orchestra Suite No. 2, strings Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel: Concerto in D Minor Wq. 22, strings Berio, Luciano: Serenata for flute and 14 instruments Bozza, Eugene: Agrestide Op. 44 (1942) orchestra Bernstein, Leonard: Halil, nocturne (1981) strings, percussion Bloch, Ernest: Suite Modale (1957) strings Bloch, Ernest: "TWo Last Poems... maybe" (1958) orchestra Borne, Francois: Fantaisie Brillante on Bizet’s Carmen orchestra Casella, Alfredo: Sicilienne et Burlesque (1914-17) orchestra Chaminade, Cecile: Concertino, Op. 107 (1902) orchestra Chen-Yi: The Golden Flute (1997) orchestra Corigliano, John: Voyage (1971, arr. 1988) strings Corigliano, John: Pied Piper Fantasy (1981) orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 7 in E Minor, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 10 in D Major, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto in D Major, orchestra Doppler, Franz: Hungarian Pastoral Fantasy, Op. 26, orchestra Feld, Heinrich: Fantaisie Concertante (1980) strings, percussion Foss, Lucas: Renaissance Concerto (1985) orchestra Godard, Benjamin: Suite Op. 116; Allegretto, Idylle, Valse (1889) orchestra Haydn, Joseph: Concerto in D Major, H. VII f, D1 Hindemith, Paul: Piece for flute and strings (1932) Hoover, Katherine: Medieval Suite (1983) orchestra Hovhaness, Alan: Elibris (name of the DaWn God of Urardu) Op. 50, (1944) Hue, Georges: Fantaisie (1913) orchestra Ibert, Jaques: Concerto (1933) orchestra Jacob, Gordon: Concerto No. -

Romanian Concerto

Brahms’ Second Symphony is one of those works that is as satisfying for an orchestra to play as it is for the audience to experience. Every note of every instrument seems to contain musical DNA of the whole. The bass part, for instance, is so well written that by itself, it is evocative of all the other voices, even when played in isolation. CRAIG BROWN, NCS DOUBLE BASS Romanian Concerto GYÖRGY LIGETI BORN May 28, 1923, in Transylvania, Romania; died June 12, 2006, in Vienna PREMIERE Composed 1951; first performance August 12, 1971, at the Peninsula Music Festival in Wisconsin OVERVIEW The son of Hungarian parents from Transylvania, György Ligeti spent his youth in Cluj, Romania, where he attended the city’s conservatory, continuing his musical studies in Budapest. In 1942, he was sent to a forced-labor camp, Hungary’s reluctant sop to Hitler’s virulent anti-Semitism; the rest of his family was annihilated when the Germans occupied Hungary in 1944 as they fled from defeat in the Soviet Union. Following the war, Ligeti resumed his studies and, in 1950, joined the faculty at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest as a harmony teacher. Until his escape from Hungary in 1956, most of his published compositions were arrangements of Romanian and Hungarian folksongs and Roma (Gypsy) melodies, while his more serious works remained unpublished since they did not conform to the politicized Soviet-style strictures. Once Ligeti had settled in the West, his music changed dramatically. In the studios of the West German Radio in Cologne, he learned the techniques of serialism and electronic music, experimenting in both systems but ultimately rejecting both. -

Ramifications of Surrealism in the Music of György Ligeti

JUXTAPOSING DISTANT REALITIES: RAMIFICATIONS OF SURREALISM IN THE MUSIC OF GYÖRGY LIGETI Philip Bixby TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 9, 2017 ________________________________ Charles Carson, Ph.D. Butler School of Music Supervisor ________________________________ Elliott Antokoletz, Ph.D. Butler School of Music Second Reader Abstract: Author: Philip Bixby Title: Ramifications of Surrealism in the Music of György Ligeti Supervisors: Charles Carson, Ph.D. Elliott Antokoletz, Ph.D. György Ligeti is considered by many scholars and musicians to be one of the late twentieth century’s most ingenious and influential composers. His music has been particularly difficult to classify, given the composer’s willingness to absorb a multitude of musical influences, everything from high modernism and electronic music to west-African music and Hungarian folk-song. One aesthetic influence that Ligeti acknowledged in the 1970s was Surrealism, an early twentieth-century art movement that sought to externalize the absurd juxtapositions of the unconscious mind. Despite the composer’s acknowledgement, no musicological inquiry has studied how the aesthetic goals of Surrealism have manifested in his music. This study attempts to look at Ligeti’s music (specifically the music from his third style period) through a Surrealist lens. In order to do this, I first establish key definitions of Surrealist concepts through a close reading of several foundational texts of the movement. After this, I briefly analyze two pieces of music which were associated with the beginnings of Surrealism, in order to establish the extent to which they are successfully Surreal according to my definitions. Finally, the remainder of my study focuses on specific pieces by Ligeti, analyzing how he is connected to but also expands beyond the “tradition” of musical Surrealism in the early twentieth century. -

Music Theory Society of New York State

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting University at Buffalo Baird Hall North Campus Buffalo, New York, NY 14260 9–10 April 2011 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:00–9:00 am Registration 9:00 am–12:00 European Modernism pm 9:00 am –10:30 Music to Serve the Story am 10:30 am –12:00 Calling Time pm 12:00–1:15 pm Lunch 1:15 pm Rebecca Hyams "The MTSNYS Archives, 40 Years Forward and 40 Years Back" 1:45–3:15 pm Temporal Pespectives in Brahms and Beethoven Nocturnal Forms 3:30–5:30 pm Keynote Address Steve Laitz (Eastman School of Music): "Sharing the Wealth: Best Practices in the 4352" 5:45 pm Business Meeting/Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:30 am Registration 9:30 am –12:30 Key Landscapes pm 9:30 am –11:00 Beatles and Beats am 11:00 am –12:30 11:00 am –12:30 Schenker pm 12:30–1:30 pm MTSNYS Board Meeting Program Committee: Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), chair; John Covach (University of Rochester), Jonathan Dunsby (ex officio, Eastman School of Music), Morewaread Farbood (New York University), Judith Lochhead (SUNY at Stony Brook). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00 am–12:00 pm European Moderism Chair: Martha Hyde (University at Buffalo) "Neither Tonal not Atonal"?: A Statistical RootMotion Analysis of Ligeti's Late Triadic Works Kris Shaffer (Yale University) Transformational Networks as Representations of Systematic Intervallic Interactions in Berio's Sinfonia C. Catherine Losada (University of Cincinnati, CollegeConservatory of Music) Freedom and Constraint: The Nature of Indiscipline in the Serial Composition of Pierre Boulez Emily Adamowicz (University of Western Ontario) Gegenstrebige Harmonik in the Music of Hans Zender Robert Hasegawa (Eastman School of Music) Program ‘Neither Tonal nor Atonal’?: A Statistical RootMotion Analysis of Ligeti’s Late Triadic Works A number of works from the latter part of György Ligeti’s career are saturated by major and minor triads and other tertian harmonies. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; please contact Carol Sesnowitz, contest coordinator, at [email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 1. VIOLIN Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bach All Violin concerti Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Stamitz All Cello concerti Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major R. Strauss Romanze in F major Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor BASS Haydn All Violin concerti Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Capuzzi Double Bass Concerto in D major Lalo Symphonie Espagnole Dittersdorf Double Bass Concerto in E major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Dragonetti All Double Bass concerti Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Koussevitsky Double Bass Concerto in F-sharp minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Vanhal Concerto for Double Bass Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major HARP Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major Alwyn Lyra angelica Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major Boieldieu Harp Concerto Paganini Violin Concert No. 1 in D major, Op. 6 Debussy Danses sacree et profane Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. -

Malcolm Mcnab : the “Crème De La Crème ” of Studio Musicians by Giovanni Santos

Reprints from the International Trumpet Guild ® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet MALCOLM MCNAB : THE “CRÈME DE LA CRÈME ” OF STUDIO MUSICIANS BY GIOVANNI SANTOS June 2015 • Page 7 The International Trumpet Guild ® (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on a single workstation that you own • Transmit an unaltered copy of this file to any single individual end-user, so long as no fee, whether direct or indirect is charged • Print a single copy of pages of this file • Quote fair use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long as the ITGJ, date, and page number are cited as the source. The International Trumpet Guild ® prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission: • Duplication or distribution of this file, the data contained herein, or printed copies made from this file for profit or for a charge, whether direct or indirect • Transmission of this file or the data contained herein to more than one individual end-user • Distribution of this file or the data contained herein in any form to more than one end user (as in the form of a chain letter) • Printing or distribution of more than a single copy of the pages of this file • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any third party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. -

Ligeti Forward

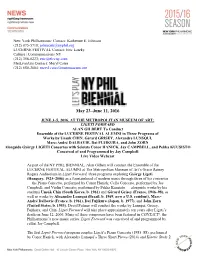

New York Philharmonic Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875 -5718; [email protected] LUCERNE FESTIVAL Contact: Eric Latzky Culture | Communications NY (212) 358-0223; [email protected] MetLiveArts Contact: Meryl Cates (212) 650-2684; [email protected] May 23–June 11, 2016 JUNE 3–5, 2016, AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART: LIGETI FORWARD ALAN GILBERT To Conduct Ensemble of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ALUMNI in Three Programs of Works by Unsuk CHIN, Gérard GRISEY, Alexandre LUNSQUI, Marc-André DALBAVIE, Dai FUJIKURA, and John ZORN Alongside György LIGETI Concertos with Soloists Conor HANICK, Jay CAMPBELL, and Pekka KUUSISTO Conceived of and Programmed by Jay Campbell Live Video Webcast As part of the NY PHIL BIENNIAL, Alan Gilbert will conduct the Ensemble of the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ALUMNI at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium in Ligeti Forward, three programs exploring György Ligeti (Hungary, 1923–2006) as a fountainhead of modern music through three of his concertos — the Piano Concerto, performed by Conor Hanick; Cello Concerto, performed by Jay Campbell; and Violin Concerto, performed by Pekka Kuusisto — alongside works by his students Unsuk Chin (South Korea, b. 1961) and Gérard Grisey (France, 1946–98), as well as works by Alexandre Lunsqui (Brazil, b. 1969, now a U.S. resident), Marc- André Dalbavie (France, b. 1961), Dai Fujikura (Japan, b. 1977), and John Zorn (United States, b. 1953). David Fulmer will conduct the works by Lunsqui, Grisey, Fujikura, and Chin. Ligeti Forward will take place approximately ten years after Ligeti’s death on June 12, 2006. Many of these composers have been featured in CONTACT!, the Philharmonic’s new-music series.