Crawdaddy Magazine – 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

"Most Likely to Succeed

Country's Tim McGraw "Most Likely To Succeed Fan Fair '94 Edition 0 82791 19359 . ) VOL, LVII, NO. 39 JUNE 11,1994 STAFF GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT Executive Vice President/ General Manager EDDIE KRITZER Executive Vice President/ Marketing (LA MARK WAGNER Director, Nashville Operations RICH NIECIECKI Managing Editor MARKETING/ADVERTISING DONALD SMITH (LA) MATTHEW SAVALAS (LA) MAXIA L. BANE (LA) INSIDE THE BOX STAN LEWIS (NY) RAFAEL A. CHARRES (Latin, NY) COVER STORY EDITORIAL Los Angeles TROY J AUGUSTO MICHAEL MARTINEZ Country’s “Most Likely To Succeed” JOHN GOFF Nashville RICHARD McVEY Liberty’s John Berry, Curb’s Bros.' Faith Hill, Rick Tim McGraw, Warner Columbia’s Trevino. RCA’s GARY KEPUNGER New York Lari White and Capricorn’s Kenny Chesney are among this year’s class of rising new artists that are RAFAEL A CHARRES. Latin Editor TED WILLIAMS “most likely to succeed.’’ Cash Box's Richard McVey profiles each of these talented newcomers. CHART RESEARCH Los Angeles —see pages 6 & 7 DANI FRIEDMAN NICOLA RAE RONCO GIL BANDEL Nashville Readies For Fan Fair TRENICE KEYES Nashville GARY KEPUNGER Country music fans who want the opportunity to get upclose and personal with their favorite stars at this Chicago year’s Fan Fair can do so with a special one-day ticket or attend the entire week’s schedule, June 6-12, CAMILLE COMPASIO Director. Coin Machine Operations PRODUCTION at the Tennessee State Fairgrounds. SHARON CHAMBUSS-TRAYLOR see page 15 — CIRCULATION NINA TREGUB, Manager Industry Buzz PASHA SANTOSO PUBLICATION OFFICES NEW YORK East Coast: Francis Dunnery lias evolved from recording and touring as a guitarist for Robert Plant to 345 W 5Sh Street Suite 15W New York, NY 10019 his own Atlantic debut Fearless. -

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title #1 Crush 19 Somethin Garbage Wills, Mark (Can't Live Without Your) Love And 1901 Affection Phoenix Nelson 1969 (I Called Her) Tennessee Stegall, Keith Dugger, Tim 1979 (I Called Her) Tennessee Wvocal Smashing Pumpkins Dugger, Tim 1982 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Travis, Randy Cutting Crew 1985 (Kissed You) Good Night Bowling For Soup Gloriana 1994 0n The Way Down Aldean, Jason Cabrera, Ryan 1999 1 2 3 Prince Berry, Len Wilkinsons, The Estefan, Gloria 19th Nervous Breakdown 1 Thing Rolling Stones Amerie 2 Become 1 1,000 Faces Jewel Montana, Randy Spice Girls, The 1,000 Years, A (Title Screen 2 Becomes 1 Wrong) Spice Girls, The Perri, Christina 2 Faced 10 Days Late Louise Third Eye Blind 20 Little Angels 100 Chance Of Rain Griggs, Andy Morris, Gary 21 Questions 100 Pure Love 50 Cent and Nat Waters, Crystal Duets 50 Cent 100 Years 21st Century (Digital Boy) Five For Fighting Bad Religion 100 Years From Now 21st Century Girls Lewis, Huey & News, The 21st Century Girls 100% Chance Of Rain 22 Morris, Gary Swift, Taylor 100% Cowboy 24 Meadows, Jason Jem 100% Pure Love 24 7 Waters, Crystal Artful Dodger 10Th Ave Freeze Out Edmonds, Kevon Springsteen, Bruce 24 Hours From Tulsa 12:51 Pitney, Gene Strokes, The 24 Hours From You 1-2-3 Next Of Kin Berry, Len 24 K Magic Fm 1-2-3 Redlight Mars, Bruno 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2468 Motorway 1234 Robinson, Tom Estefan, Gloria 24-7 Feist Edmonds, Kevon 15 Minutes 25 Miles Atkins, Rodney Starr, Edwin 16th Avenue 25 Or 6 To 4 Dalton, Lacy J. -

Karaoke Songs We Can Use As at 22 April 2013

Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. TKS No. SONG TITLE IN THE STYLE OF 21273 Don't Tread On Me 311 25202 First Straw 311 15937 Hey You 311 1325 Where My Girls At? 702 25858 Til The Casket Drops 16523 Bye Bye Baby Bay City Rollers 10657 Amish Paradise "Weird" Al Yankovic 10188 Eat It "Weird" Al Yankovic 10196 Like A Surgeon "Weird" Al Yankovic 18539 Donna 10 C C 1841 Dreadlock Holiday 10 C C 16611 I'm Not In Love 10 C C 17997 Rubber Bullets 10 C C 18536 The Things We Do For Love 10 C C 1811 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 24657 Hot And Wet 112/ Ludacris 21399 We Are One 12 Stones 19015 Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company 26221 Countdown 2 Chainz/ Chris Brown 15755 You Know Me 2 Pistols & R Jay 25644 She Got It 2 Pistols/ T Pain/ Tay Dizm 15462 Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down 23044 Everytime You Go 3 Doors Down 24923 Here By Me 3 Doors Down 24796 Here Without You 3 Doors Down 15921 It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down 15820 Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down 25232 Let Me Go 3 Doors Down 22933 When You're Young 3 Doors Down 15455 Don't Trust Me 3 Oh!3 21497 Double Vision 3 Oh!3 15940 StarStrukk 3 Oh!3 21392 My First Kiss 3 Oh!3 / Ke$ha 23265 Follow Me Down 3 Oh!3/ Neon Hitch 20734 Starstrukk 3 Oh3!/ Katy Perry 10816 If I'd Been The One 38 Special 10112 What's Up 4 Non Blondes 9628 Sukiyaki 4.pm 15061 Amusement Park 50 Cent 24699 Candy Shop 50 Cent 12623 Candy Shop 50 Cent 1 Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. -

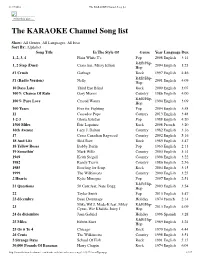

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Toronto Star 1999

THE RETURN OF JESSE WINCHESTER New Offering Ends Singer's 11-Year Recuperative Silence PUBLISHED IN THE TORONTO STAR, Sunday, September 19, 1999 By Nick Krewen Silver-tongued songwriter JESSE WINCHESTER is eleven years wiser and his hair a little greyer since we last heard from him with his 1988 album Humour Me . He's back in 1999 with Gentleman's Leisure, and one might assume from the album's title that his absence included some down time cavorting on a luxurious yacht, sipping pina coladas and soaking up Mediterrean rays. Yeah. Right. "I just got burnt out," admits Winchester, whose stature through ten albums and 28 years has always been more satellite than star, orbiting the peripheral between respectability and reverence. "I was discouraged. I was repeating myself. I felt I was saying the same thing in concert every night. It made me feel awful. "And it seemed like the only thing that was making me money -- or ever had made me any money -- was writing songs for other people. So I decided to just quit and write songs for other people." Known for his clever, gentle odes of laid-back, relaxed country blues, often salted with a slight Memphis swing -- the lust-laden "Isn't That So" and the humorous marijuana anthem "Twigs And Seeds" are prime examples -- Winchester has been overlooked when it comes to scoring the big hit. Even album sales have been nominal, despite such acclaimed earlier classics as his ROBBIE ROBERTSON-produced Jesse Winchester debut, or Third Down, 110 To Go, overseen by TODD RUNDGREN. -

The Mavericks Biography

The Mavericks Biography Raul Malo: Vocals, Guitar Paul Deakin: Drums Jerry Dale McFadden: Keyboards, Vocals Eddie Perez: Lead Guitar, Vocals “Beyond category” is the only label that truly suits Grammy Award winning group, The Mavericks. As Entertainment Weekly noted in 2017, “‘What kind of music do The Mavericks record?’ is a question with no real answer. On the one hand, the Miami-bred outfit records bits of everything: Elvis Presley-esque rock, Roy Orbison-style balladry, Latin-fusion party tunes, throwback country, irresistible pop. On the other hand…a vocabulary for their style remains out of reach.” The band has resolutely defied pigeonholing since their founding in 1989; they played their earliest dates in Florida’s alternative rock clubs, where their on-stage contemporaries included another new act on the scene, Marilyn Manson. The Mavericks’ eclectic sound – fronted by a Cuban-American vocalist and songwriter who drew strongly on his Latin/Caribbean roots, and flexing a panoply of influences drawn from rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly, pop balladry, blues, R&B, and jazz -- ultimately fit most comfortably in a country pocket, and in 1991 the group was signed to MCA Records’ Nashville division. It took the band a couple of albums to find their commercial footing, but in 1994 they launched a bona fide hit with their third collection, the No. 6 country album What A Crying Shame. The set’s title number, which climbed to No. 25 on the country charts and remained on the charts for six months, was the first of many early hits penned by lead singer Raul Malo and his frequent writing partner Kostas, and the first of four singles to reach the country top 30 in 1994-95. -

Rhythm & Blues...37 Pricelist/Preisliste...96

1 COUNTRY .......................2 POP.............................57 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............14 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................63 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......15 LATIN ............................65 WESTERN..........................17 JAZZ .............................65 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................18 SOUNDTRACKS .....................66 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........19 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....19 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............66 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......19 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............70 BLUEGRASS ........................20 INSTRUMENTAL .....................22 BOOKS/BÜCHER ................71 OLDTIME ..........................23 CHARTS ..........................77 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................23 TEXMEX ...........................24 DVD ............................77 FOLK .............................24 VINYL...........................84 ROCK & ROLL ...................26 LABEL R&R .........................33 ARTIST INDEX...................88 R&R SOUNDTRACKS .................35 ORDER TERMS/VERSANDBEDINGUNGEN..95 ELVIS .............................36 PRICELIST/PREISLISTE ...........96 RHYTHM & BLUES...............37 GOSPEL ...........................39 BEAR TIPs .......................38 SOUL.............................40 VOCAL GROUPS ....................42 LABEL DOO WOP....................43 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................44 SURF .............................49 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............51 BRITISH R&R ........................54 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............55 BEAR FAMILY -

O What a Thrill

O What A Thrill Choreo: Larry & Susan Sperry, 40 Roundup Drive, Billings, MT 59102 version 1.3 Website: www.larrysperry.com E-mail [email protected] Music: O What A Thrill by the Mavericks, Album; What A Crying Shame, Trk 9, length 3:13 Amazon download Footwork: Opposite unless noted (Woman’s footwork in Parentheses) Rhythm: Rumba Phase 3 Degree of Difficulty: Average Sequence: Intro A B inter A B end INTRODUCTION 1-4 WRAPPED BOTH FCNG WALL WAIT 2 MEAS;; WHEEL 3; WHEEL 3 UNWRAP BFLY; 1-4 Wrapped pos both fcng wall with lead feet free wait 2 meas;; Wheel fwd L, fwd R, fwd L,-, to fc COH; Raising lead hands wheel fwd R, fwd L, fwd R,-, (W unwrap RF keeping hands joined L, R, L,-); PART A 1-4 HAND TO HAND; SPOT TURN TWICE;; NEW YORKER; 1-2 Swivel sharply ¼ LF on R rk bk L, rec R to bfly, sd L,-; XRif comm LF turn, cont trn rec L to fc, sd R,-; 3-4 XLif comm RF turn, cont trn rec R to fc, sd L,-; Swiveling on L thru R, rec L, sd R,-; 5-8 SHLDR TO SHLDR TWICE;; REV UNDERARM TURN; UNDERARM TURN RT HNDSHK; 5-8 Fwd L to bfly scar, rec R, sd L,-; Fwd R to bfly bjo, rec L, sd R,-; XLif, rec L, sd R,- (Under jnd hnds W XRif of L trng ½ LF, cont trng ½ LF rec L to fc ptr, Sd R,-); XRib raise lead arms, rec L, sd R to R hndshk,- (Woman XLIF of R trng ½ RF, cont trng ½ RF rec R to fc ptr, Sd L,-); 9-12 SHADOW NEW YORKER; WHIP; SHADOW NEW YORKER; WHIP 9-10 Swivel RF ¼ step thru L, rec R, sd L-; Bk R trn ¼ LF, rec fwd L trn ¼ LF, sd R,- (W fwd L outside M, fwd R turning ½ LF, sd L,-); 11-12 Repeat meas 9-10 part A to fc wall;; 13-16 CHASE TO R