“Phans”, Not Fans”: the Phantom and Australian Comic-Book Fandom1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

La Imagen De La Historia En Terry Y Los Piratas De Milton Caniff

La Imagen de la Historia en Terry y los Piratas de Milton Caniff Francisco Manuel Saez de Adana Herrero Tutor: Iván Pintor Iranzo Curs 2013/2014 Treballs de recerca dels programes de postgrau del Departament de Comunicació Departament de Comunicació Universitat Pompeu Fabra Resumen En este trabajo se presenta el reflejo de la historia en el cómic de prensaTerry y los Piratas de Milton Caniff. Se analiza cómo el autor se convierte, a través de una obra de aventuras, en un cronista de la historia y, fundamentalmente, de los acontecimientos que sucedían en China en los años anteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Constituye un acercamiento de una realidad lejana en una época en que la so- ciedad americana sólo miraba a su interior, preocupada por su situación económica fruto de la Gran De- presión. Todos estos condicionantes de la sociedad norteamericana tienen su reflejo en el cómic de prensa en general y en Terry en los Piratas en particular, aspecto que se estudia en este trabajo. La potencialidad de la imagen y del cómic como transmisor de la historia es el eje fundamental del análisis realizado. Palabras clave: cómic de prensa, Terry y los Piratas, Milton Caniff, historia, sociedad norteamericana. Agradecimientos En primer lugar quería agradecer a Iván Pintor, mi tutor en este trabajo, por haberme abierto el cami- no hacia la realización de un sueño: la realización de una tesis doctoral sobre el cómic de prensa. Algo que durante muchos años creí imposible y que, con este trabajo, empieza a tomar forma. Gracias por confiar en este ingeniero que se mete en el mundo de las humanidades con la mayor de las ilusiones. -

Karakter Lothar Dan Lobo Dalam Komik Amerika

Lingua XV (1) (2019) LINGUA Jurnal Bahasa, Sastra, dan Pengajarannya Terakreditasi Sinta 3 berdasarkan Keputusan Dirjend Penguatan Riset dan Pengembangan, Kemenristek Dikti No 21/E/KPT/2018 http://journal.unnes.ac.id/nju/index.php/lingua IDENTItaS dan REPRESEntaSI: KARAKTER LothaR dan LOBO dalam KomIK AMERIKA Tisna Prabasmoro Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran Jln. Raya Bandung-Sumedang KM 21 Jatinangor, Sumedang Jawa Barat, Indonesia Telepon (022)7796482 Faksimile (022) 7796482 Info Artikel Abstrak Sejarah artikel: Komik bergenre jawara adidaya dapat menjadi sumber inspirasi dan Diterima mendemonstrasikan penanda moral yang berfaedah bagi masyarakat. Mengabaikan September 2018 beberapa aspek identitas yang problematis akan menjauhkan usaha-usaha konstruktif Disetujui yang diperlukan. Sementara penggambaran karakter perempuan, kelompok minoritas, dan homoseksual terus meningkat dari waktu ke waktu dalam hal representasi dan Desember 2018 karakterisasi nonstereotip, kontrol baku karakter jawara adidaya tetap saja berkulit Dipublikasikan putih. Karakter dari kelompok minoritas yang muncul di era awal buku komik Januari 2019 Amerika diperankan sebagai penjahat, bukan jawara adidaya/pahlawan. Penelitian ini menceritakan dan mengkaji representasi rasial dan perusakan budaya jawara Kata Kunci: adidaya berkulit hitam bernama Lothar dan Lobo yang muncul pada komik-komik identitas; perdana jawara adidaya Amerika. Penelitian ini berargumen bahwa representasi representasi; berfungsi sebagai templat untuk menggambarkan bagaimana jawara adidaya yang jawara adidaya; tidak berwarna kulit putih terus menerus tidak dihargai dan dikendalikan terlepas Lothar; Lobo dari ingatan kolektif mereka yang dalam perspektif sejarahnya sangat kompleks. Bagian akhir penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa Lothar dan Lobo secara retoris Keyword: mengalami perlakuan rasis agar tetap berterima dengan denyut konsep-konsep identity; supremasi. representation; superhero; Lothar; Lobo Abstract The superhero genre comics can be inspirational and demonstrate moral codes that benefit society. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

(Mr) 3,60 € Aug18 0015 Citize

Συνδρομές και Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018 (για Οκτώβριο- Nοέμβριο 2018) Μέχρι τις 17 Αυγούστο, στείλτε μας email στο [email protected] με θέμα "Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018": Ονοματεπώνυμο Username Διεύθυνση, Πόλη, ΤΚ Κινήτο τηλέφωνο Ποσότητα - Κωδικό - Όνομα Προϊόντος IMAGE COMICS AUG18 0013 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR A BARTEL 3,60 € AUG18 0014 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR B STAPLES (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0015 CITIZEN JACK TP (APR160796) (MR) 13,49 € AUG18 0016 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 01 (MAR170820) 8,49 € AUG18 0017 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 02 (MAR180718) 15,49 € AUG18 0018 DEAD RABBIT #1 CVR A MCCREA (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0020 INFINITE HORIZON TP (FEB120448) 16,49 € AUG18 0021 LAST CHRISTMAS HC (SEP130533) 22,49 € AUG18 0022 MYTHIC TP VOL 01 (MAR160637) (MR) 15,49 € AUG18 0023 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR A KOUTSIS 3,60 € AUG18 0024 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR B LARSEN 3,60 € AUG18 0025 POPGUN GN VOL 01 (NEW PTG) (SEP071958) 26,99 € AUG18 0026 POPGUN GN VOL 02 (MAY082176) 26,99 € AUG18 0027 POPGUN GN VOL 03 (JAN092368) 26,99 € AUG18 0028 POPGUN GN VOL 04 (DEC090379) 26,99 € AUG18 0029 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR A LAGACE 3,60 € AUG18 0030 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR B GUERRA 3,60 € AUG18 0033 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 01 (SEP120436) 8,49 € AUG18 0034 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 02 REBIRTH (APR150581) 8,49 € AUG18 0035 PLUTONA TP (MAR160642) 15,49 € AUG18 0036 INFINITE DARK #1 3,60 € AUG18 0037 HADRIANS WALL TP (JUN170665) (MR) 17,99 € AUG18 0038 WARFRAME TP VOL 01 (O/A) 17,99 € AUG18 0039 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR A MARTINEZ (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0040 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR B HAWTHORNE (MR) 3,60 -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Phantom Free Download

PHANTOM FREE DOWNLOAD Terry Goodkind | 400 pages | 04 Jun 2007 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007145652 | English | London, United Kingdom Try Premium for Free Sasha Julian Adams You should know that. Phantom Diana Palmer Guran. During his first story, "The Singh Brotherhood", before disclosing that Wells was the Phantom, Falk changed the setting to a jungle and made the Phantom an apparently immortal, mythic figure. User Ratings. Sophi Derek Phantom The rest of the film was pretty much a combination of Red Phantom and The Abyss how come nobody noticed that? Don Cort, despite his four Phantom stars, was telling Phantom he must not let these middle-aged Phantom make him feel like a boy. The server shutdown time will be announced separately. Navy's Pacific fleet for nuclear attack, it appears that the final battle has begun. Sensor does not work. The series began with a daily newspaper strip on February 17,followed by a color Sunday strip on May 28, ; both are still running as of Phantom I've read the reviews of others and I was surprised Phantom see such a strong polarizing. Please check if there are Phantom that could be blocking the satellite signal. Accessed 21 Oct. Purchase Online! Words Phantom phantom phantasmagoriaphantasmagoricphantasmagoryphantasmalphantasyphantomphantom circuitphantom corpusclephantom limbphantom limb painphantom pregnancy. End of the Road Finale, 23 shot. Harvey Comics published The Phantom during the s. Phantom Meadow Flower Fountain. People either loved or completely hated the film. Weight Single Use the -

David Aronoff Partner

David Aronoff Partner [email protected] Los Angeles, CA Tel: 310.228.2916 Fax: 310.556.9828 A seasoned entertainment and media law attorney, David has more than 30 years of experience handling a variety of complex matters, including breach of contract, copyright, trademark, right of publicity, accounting and defamation claims. David regularly represents and advises a variety of business entities, including motion picture and television studios, production companies, broadcasters, Internet websites and podcasters, video game companies, music companies and advertising agencies in their business and marketing decisions and disputes involving: • Copyrights • Trademarks • Right of publicity • Unfair competition • Trade secrets • False advertising • Contracts/accounting/finance He has handled numerous infringement and idea submission claims concerning popular entertainment works and hit movies such as “The Last Samurai,” “Along Came Polly,” “Reality Bites,” “There’s Something About Mary” and “The Mask of Zorro.” Among his recent cases, David conducted a two-week bench trial concerning the financing and distribution of the videogame “Def Jam Rapstar,” defended the in-development spy-thriller project “Section 6” against claims that it infringed the copyrights in the character James Bond, and represented keyboardist-songwriter Jonathan Cain of the rock group “Journey” in acrimonious trademark litigation between the band’s members concerning the ownership and control of the “Journey” band name and trademarks. Representative Matters • Guity v. Romeo Santos/Sony Music, 2019 WL 6619217 (S.D.N.Y. 2019) (won MTD resulting in dismissal of copyright infringement claims against Romeo Santos’ hit song “Eres Mia” on the grounds that defendants’ song, as a matter of law, was not substantially similar to plaintiff’s allegedly infringed song of the same title). -

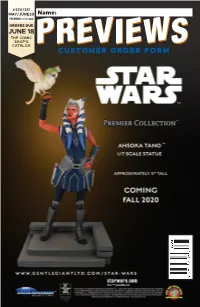

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

A PRAGMATIC ANALYSIS of DIRECTIVE UTTERANCE on the SECRET of VACUL CASTLE's COMIC STRIP PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submited As A

A PRAGMATIC ANALYSIS OF DIRECTIVE UTTERANCE ON THE SECRET OF VACUL CASTLE’S COMIC STRIP PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submited as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by Surya Setiawan A320090251 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2014 A PRAGMATIC ANALYSIS OF DIRECTIVE UTTERANCE ON THE SECRET OF VACUL CASTLE’S COMIC STRIP Surya Setiawan A320 090 251 This article is a qualitative research. This article is to describes the meaning of directive utterance, and to analyze the politeness pattern of each directive utterance found in The Secret of Vacul Castle’s comic strip. The data are taken from The Secret of Vacul Castle’s comic strip. The methods of collecting data is documentation. The writer collets the data by reading The Secret of Vacul Castle’s comic strip, classifying the serial which contains directive utterances, underlining the directive utterances found in The Secret of Vacul Castle’s comic, and coding the collected data in the list, in which data list of the data number. The techniques of analyzing data are describing the story context of The Secret of Vacul Castle’s comic strip serial, explaining the illocutionary act on the directive utterances found in The Secret of Vacul Castle comic strip serials, determining the category of directive utterances found in The Secret of Vacul Castle comic strip serials, analyzing the politeness strategy used on the directive utterances found in The Secret of Vacul Castle comic strip serials and