Islamist Militant Threats to Eurasia Joint Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representative Paul Cook 6 116Th United States Congress 395 95

93 80 95 6 50 70 15 Representative Paul Cook 6 116th United States Congress 395 95 California's 893TH Congressional District 5 89 The 8 federally-funded health center organizations with a presence in California's15 8th Congressional District leverage $37,279,026 in federal investments to serve 390,271 patients. ¤£ §¨¦ ¤£ Nevada95 395 £ ¤£Folsom ¤ §¨¦ Rancho Cordova !( 101 5 §¨¦ 515 Lodi Utah 93 ¤£ 15 Manteca ¤£ Mono ¤£ 95 Ceres County Modesto Turlock ¤£ 40 §¨¦ 15 5 ¤£ Merced 395 40 §¨¦ 101 40 Madera 15 93 Clovis Fresno !( Inyo ¤£ California County 95 Visalia 101 Hanford ¤£210 Pahrump North Las Vegas Tulare 215 10 Spring Valley Sunrise Manor ¤£ §¨¦ 405 605 5 Henderson 60 Paradise Porterville !( §¨¦ 10 ¤£ Delano §¨¦ Arizona Oildale Ridgecrest ¤£ Bakersfield San Luis Obispo !( §¨¦ §¨¦ San Orcutt §¨¦ Bernardino Santa Maria ¤£ !( County !( ¤£ Lancaster §¨¦ §¨¦ Lompoc Palmdale §¨¦ Goleta Santa Clarita !( ¤£ !(!( Apple Valley Lake Havasu City Santa Barbara Simi Valley Hesperia Victorville Ventura GlendalePasadena Highland ¤£ Oxnard ¤£ §¨¦ !( Yucaipa !(!( !( Santa Monica Fullerton Corona Torrance §¨¦ §¨¦ 0 20 40 80 §¨¦§¨¦ Indio §¨¦ Irvine ¤£ Huntington Beach Costa Mesa §¨¦ Miles - Federally-funded site 116th Congressional (each color represents one organization) District Boundaries Major Highways County Boundaries NUMBER OF DELIVERY SITES IN Highways City or Town CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 18 Major Roads Notes | Delivery sites represent locations of organizations funded by the federal Health Center Program. Some locations may overlap due to scale or may otherwise not be visible when mapped. Federal investments represent the total funding from the federal Health Center Program to grantees with a presence in the state in 2017. Sources | Federally-Funded Delivery Site Locations: data.HRSA.gov, December 3, 2018. Health Center Patients and Federal Funding | 2017 Uniform Data System, Bureau of Primary Health Care, HRSA. -

The Struggles of Recovering Assets for Holocaust Survivors Joint Hearing Committee on Foreign Affairs House of Representatives

THE STRUGGLES OF RECOVERING ASSETS FOR HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE, EURASIA, AND EMERGING THREATS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 Serial No. 113–210 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 89–815PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:47 Oct 22, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_MENA\091814\89815 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

Outlook for the New Congress

Outlook for the New Congress Where are we going • FY 2015 operating under CR • Omnibus Release Date – December 8 (source - House Appropriations) • Expires on December 11 • Current goal: omnibus bill • Other possibilities: CR through March 31; full year CR • FY 2015 Defense Authorization • FY 2016 budget process • Return to “regular order?” • Another budget agreement? 2 2014 Senate Results Chart The GOP takes control 3 2014 House Results Chart The GOP expands their majority 184 244 4 Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee Democratic Subcommittee Members Republican Subcommittee Members • Dianne Feinstein (CA), Likely RM • Lamar Alexander (TN), Likely Chair • Patty Murray (WA) • Thad Cochran (MS) • Tim Johnson (SD) • Mitch McConnell (KY)* • Mary Landrieu (LA) ??? • Richard Shelby (AL) • Tom Harkin (IA) • Susan Collins (ME) • Jon Tester (MT) • Lisa Murkowski (AK) • Richard Durbin (IL) • Lindsey Graham (SC) • Tom Udall (NM) • John Hoeven (ND) • Jeanne Shaheen (NH) [Harry Reid – Possible RM] *as Majority Leader, McConnell may take a leave of absence from the Committee 5 House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee Republican Subcommittee Members • Michael Simpson (ID), Chair • Rodney P. Frelinghuysen (NJ) Democratic Subcommittee • Alan Nunnelee (MS), Vice Chair Members • Ken Calvert (CA) • Marcy Kaptur (OH), RM • Chuck Fleishmann (TN) • Pete Visclosky (IN) • Tom Graves (GA) • Ed Pastor (AZ) • Jeff Fortenberry (NE) • Chaka Fattah (PA) 6 Senate Armed Services Republican Subcommittee Democratic Subcommittee Members Members -

Workers Need More Friends in Government

UFCW Official Publication of Local 1167, United Food and Commercial Workers Union October 2012 Tentative agreement with Rite Aid submitted VOTE! to members in So. Calif. he seven UFCW unions in Southern California reached a tentative agreement with Rite Aid on Sept. 25. The pro- posed contract was promptly submitted to Rite Aid’s T union members for ratification. Results of the ratification vote and details and details of the agreement will be featured in the next issue of the Desert Edge. The agreement was announced by leaders of UFCW Locals 8, 135, 324, 770, 1167, 1428 and 1442, which represent Rite Aid PRESIDENT’S REPORT workers between Kern County and the Mexican border. “I am so proud of you for sticking together in the quest to protect your health benefits,” UFCW Local 1167 President Workers need more Bill Lathrop told the Rite Aid members. “Thank you for your strength and solidarity!” friends in government s the Nov. 6 elections draw closer, Califor ni ans are reading up on the candi- dates and issues. A . C A 5 G Some of us may default to vot- , 8 R O E 2 O N G I 2 A ing along party lines, but as we T . D T I D O R F S I A N O O A consistently tell our members, N P R T P I R . P - E S M . N B R party affiliation is not the only fac- U E O N P N A S tor to consider when deciding whether a candidate deserves your vote. -

Lobbying Contribution Report

8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report LOBBYING CONTRIBUTION REPORT Clerk of the House of Representatives • Legislative Resource Center • 135 Cannon Building • Washington, DC 20515 Secretary of the Senate • Office of Public Records • 232 Hart Building • Washington, DC 20510 1. FILER TYPE AND NAME 2. IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS Type: House Registrant ID: Organization Lobbyist 35195 Organization Name: Senate Registrant ID: Honeywell International 57453 3. REPORTING PERIOD 4. CONTACT INFORMATION Year: Contact Name: 2016 Ms.Stacey Bernards MidYear (January 1 June 30) Email: YearEnd (July 1 December 31) [email protected] Amendment Phone: 2026622629 Address: 101 CONSTITUTION AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001 USA 5. POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE NAMES Honeywell International Political Action Committee 6. CONTRIBUTIONS No Contributions #1. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Friends of Sam Johnson Sam Johnson #2. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Kay Granger Campaign Fund Kay Granger #3. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Paul Cook for Congress Paul Cook https://lda.congress.gov/LC/protected/LCWork/2016/MM/57453DOM.xml?1470093694684 1/75 8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report #4. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: DelBene for Congress Suzan DelBene #5. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: John Carter for Congress John Carter #6. -

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

2019 Political Contributions

MEPAC Disbursement Political Contributions 2019 Lockheed Martin 2019 LMEPAC Disbursements State Member Party Office District Total ALASKA Lisa Murkowski for US Senate Murkowski, Lisa R U.S. SENATE $2,000.00 True North PAC Sullivan, Daniel R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Sullivan For US Senate Sullivan, Daniel R U.S. SENATE $8,000.00 Alaskans For Don Young Young, Don R U.S. HOUSE AL $5,000.00 ALABAMA RBA PAC (Reaching for Brighter America) Aderholt, Robert R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Aderholt for Congress Aderholt, Robert R U.S. HOUSE 4 $6,000.00 Mo Brooks for Congress Brooks, Mo R U.S. HOUSE 5 $6,000.00 Byrne For Congress Byrne, Bradley R U.S. HOUSE 1 $5,000.00 Seeking Justice Committee Jones, Doug D Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Doug Jones For Senate Jones, Doug D U.S. SENATE $9,000.00 Gary Palmer For Congress Palmer, Gary R U.S. HOUSE 6 $1,000.00 MARTHA PAC Roby, Martha R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Martha Roby For Congress Roby, Martha R U.S. HOUSE 2 $4,000.00 American Security PAC Rogers, Mike R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Mike Rogers For Congress Rogers, Mike R U.S. HOUSE 3 $9,000.00 Terri PAC Sewell, Terri D Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Terri Sewell For Congress Sewell, Terri D U.S. HOUSE 7 $4,000.00 Defend America PAC Shelby, Richard R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 ARKANSAS Arkansas for Leadership PAC Boozman, John R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Cotton For Senate Cotton, Tom R U.S. -

Congressional List 219 Representatives and 39 Senators

Taxpayer Protection Pledge I, ____________, pledge to the taxpayers of the _____district of the state of _________ and to the American people that I will: One, oppose any and all efforts to increase the marginal income tax rates for individuals and/or businesses; and Two, oppose any net reduction or elimination of deductions and credits, unless matched dollar for dollar by further reducing tax rates. For more information contact Adam Radman, Grassroots Campaign Manager, at [email protected] FEDERAL TAXPAYER PROTECTION PLEDGE 113TH CONGRESSIONAL LIST 219 REPRESENTATIVES AND 39 SENATORS ALABAMA COLORADO ILLINOIS Richard Shelby (SEN) Scott Tipton (CO-03) Mark Kirk (SEN) Jeff Sessions (SEN) Cory Gardner (CO-04) Peter Roskam (IL-06) Jo Bonner (AL-01) Doug Lamborn (CO-05) Randy Hultgren (IL-14) Martha Roby (AL-02) Mike Coffman (CO-06) John Shimkus (IL-15) Mike Rogers (AL-03) Adam Kinzinger (IL-16) Robert Aderholt (AL-04) FLORIDA Aaron Schock (IL-18) Mo Brooks (AL-05) Marco Rubio (SEN) Spencer Bachus (AL-06) Jeff Miller (FL-01) INDIANA Steve Southerland (FL-02) Dan Coats (SEN) ALASKA Ander Crenshaw (FL-04) Marlin Stutzman (IN-03) Lisa Murkowski (SEN) Ron Desantis (FL-06) Todd Rokita (IN-04) Don Young (AK-AL) John Mica (FL-07) Luke Messer (IN-06) Bill Posey (FL-08) Larry Buschon (IN-08) ARIZONA Daniel Webster (FL-10) Todd Young (IN-09) John McCain (SEN) Richard Nugent (FL-11) Paul Gosar (AZ-04) Gus Bilirakis (FL-12) IOWA Matt Salmon (AZ-05) Bill Young (FL-13) Tom Latham (IA-03) David Schweikert (AZ-06) Dennis Ross (FL-15) Steve King (IA-04) Trent -

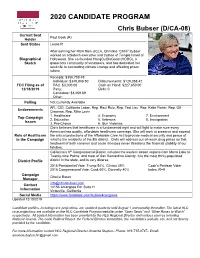

2020 Candidate Program

2020 CANDIDATE PROGRAM Chris Bubser (D/CA-08) Current Seat Paul Cook (R) Holder Seat Status Leans R After earning her MBA from UCLA, Christine “Chris” Bubser worked as a biotech executive and trustee of Temple Israel of Biographical Hollywood. She co-founded HangOutDoGood (HODG), a Sketch grassroots community of volunteers, and has dedicated her adult life to combatting climate change and affecting prison reform. Receipts: $356,708.49 Individual: $349,848.50 Disbursements: $129,058.42 FEC Filing as of PAC: $3,000.00 Cash on Hand: $227,650.00 12/18/2019 Party: Debt: 0 Candidate: $3,459.69 Other: Polling Not Currently Available AFL-CIO, California Labor, Rep. Raul Ruiz, Rep. Ted Lieu, Rep. Katie Porter, Rep. Gil Endorsements Cisneros, Rep. Mike Levin 1. Healthcare 4. Economy 7. Environment Top Campaign 2. Education 5. Veterans 8. Immigration Issues 3. Pro-Choice 6. Gun Violence Chris believes that healthcare is a fundamental right and will fight to make sure every American has quality, affordable healthcare coverage. She will work to preserve and expand Role of Healthcare the critical protections of the Affordable Care Act to provide medical security and peace of in the Campaign mind to the residents of the 8th district. Chris will address out-of-reach drug prices so that treatment of both common and acute illnesses never threatens the financial stability of our families. California’s 8th Congressional District includes the eastern desert regions from Mono Lake to Twenty-nine Palms, and most of San Bernardino County. It is the most thinly-populated District Profile district in the state, and is very diverse. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

545-562 Kendzior Fall 06

Inventing Akromiya: The Role of Uzbek Propagandists in the Andijon Massacre SARAH KENDZIOR Abstract: Many have claimed that the alleged terrorist group Akromiya incited the violence in the city of Andijon, Uzbekistan, in May 2005. This article contends that the portrayal of Akromiya as a violent organization is highly suspect and may have been created by members of the Uzbek government and propagated by mem- bers of the international scholarly community. Key words: Akromiya, Andijon, Islam, propaganda, terrorism, Uzbekistan Introduction n May 16, 2006, a group of scholars, policy experts, and journalists convened O at the Hudson Institute in Washington, DC, for the unveiling of a video that promised to reveal the truth about the violent events in the city of Andijon, Uzbek- istan, one year before. “This video demonstrates that the organizers of the upris- ing may not have been, as some have claimed, ‘peaceful Muslims,’” proclaimed the cohosts of the event, Zeyno Baran of the Hudson Institute and S. Frederick Starr of the Central Asia Caucasus Institute, in an invitation to colleagues.1 According to Baran and Starr, this new video, which had been made available to them by the Uzbek embassy, would put to rest reports declaring the Andijon events to be a Tiananmen Square-style massacre of defenseless citizens by the Uzbek government. Proof of the falseness of this allegation, they claimed, lies in the fact that the video “shows clips recorded by members of Akromiya (a Hizb- ut Tahrir splinter group) during the uprising in Andijon on May 14, 2005.”2 Roughly twenty-six minutes long, the video consisted of three main parts: clips of remorseful Akromiya members pleading for the forgiveness of the government; conversations with alleged witnesses and victims; and an interview with Shirin Akiner, a professor and close colleague of Starr who has condemned Akromiya and supported Uzbek President Islam Karimov’s claim that the use of force was Sarah Kendzior recently completed her MA in Central Eurasian studies at Indiana Uni- versity. -

Islamic Revival in Post-Independence Uzbekistan

Islamic Revival in Post-Independence Uzbekistan JAMSHID GAZIEV Islamic slogans are always used as a doctrine and not a religious one, but as a political doctrine and mostly as a means of attaining quite definite political aims. Barhold V.V. This paper will sek to analyze the revival of Islam in Uzbekistan after a century of suppression. Islamic revivalism emerged during the last decade of the Soviet Union and has since played a significant role in the politics and society of the state. The author’s main aim is to explore the political consequences, either positive or negative, caused by the revival of Islam. The paper will examine the factors that promoted the resurgence of Islam, paying attention to the present government’s position towards Islamic revival, and the changes occurring in domestic policy due to the Islamization of society. The concept that Islam plays a significant role in forming self-identity, and is confused and intertwined with other national and regional identities will be analyzed throughout this paper. In order to illustrate the political scene in Uzbekistan, Islam’s division on both horizontal and vertical levels in terms of indoctrination and institutionalization will be discussed in detail. Finally, as it poses a major challenge to the stability and prosperity of the country, Islamic fundamentalism, and wahhabism in particular, will also be discussed. Factors and Determinants of Islamic Revival in Uzbekistan The most significant event in the cultural and spiritual life of Uzbekistan since the mid-1980s was the return of Islam to its proper place in society. At last it can be stated that liberty of conscience and religion has become a reality.