Exit Interview with OLIVER (OLLIE) ATKINS on November 21, 1974

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

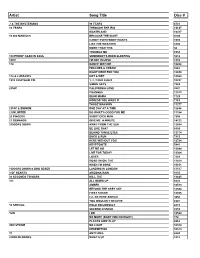

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

New Mexico State Record, 08-17-1917 State Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 8-17-1917 New Mexico State Record, 08-17-1917 State Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_state_record_news Recommended Citation State Publishing Company. "New Mexico State Record, 08-17-1917." (1917). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nm_state_record_news/58 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW MEXICO STATE RECORD SUBSCRIPTION $1.50 SANTA NEW MEXICO FE, FRIDAY AUGUST 17, 1917 NUMBER 150 - "MOTOR MINUTE MEN- HOW WOMEN ARE WORK SHOULD HAVE A RAILROADS CAN EARNINGS OF PHELPS-DODG- E T ARE BEING LINED UP NOW GETTING WHEAT AW" MAIfCDC ING NATION. PAST SIX MONTHS $I5,000,WM COMMITTEE ON "New Mexico Motor Minute Men' SPARE MEN FOR In order to define clearly the func- READY FOR WIN- - It form an uniuue. is estimated that the earnings SHOULD STAY IN organization that u tions of the Woman's Committed nf of the Phelns.rindm. Cnmnrafinn foi-- will be able to over the EXPENDITURES They get FRANCE c?uncil. of Defense - lh firs in ground rather more swiftly than the LOOMIS TER PLANTING . w"e ;l SESSION FOR WAR Minute Men of the and ui .pij.uw.uw.i?" mis was equal Revolution, woman s Committee has issued tots$34 a share against which there ONLY WAY TO MAKE PROPER wlU De " ,ess patriotic, their vai 'f,ullc,in. -

Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Adam Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation: Deep Space Nine. It's a Star Pranica Trek podcast by... a couple of guys who are just a little bit embarrassed about having a Star Trek podcast. I'm Adam Pranica. 00:00:26 Ben Harrison Host I'm Ben Harrison. And it's a MaxFunDrive episode. [Music fades out.] And it's also... a drunkisode. 00:00:34 Adam Host You shouldn't believe that those things are related in any way but luck. Like, we don't have to drink our way through a MaxFunDrive episode. That's not what anyone's saying. 00:00:44 Ben Host Yeah. And I mean I guess, like, in the past, our MaxFunDrive episodes, we've edited out the pledge breaks. 00:00:50 Adam Host Mm-hm. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Page | 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. WAYNE SHORTER NEA Jazz Master (1998) Interviewee: Wayne Shorter (August 25, 1933-) Interviewer: Larry Appelbaum and audio engineer Ken Kimery Dates: September 24, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Description: Transcript. 26 pp. Shorter: ...his first three months’ royalty on “Sunny”... It was something... He didn’t have to play the bass. He said, “I’m not playing the bass...” He played in this club, at a restaurant... They’d shot a long scene in there, and did the...well, the thing that was...the Billy Strayhorn thing...you know, that Duke Ellington recorded... “Something in Paris.” [SINGS REFRAIN] Appelbaum: From An American In Paris? Shorter: [CONTINUES TO SING REFRAIN] That song that a lot of singers find hard to sing. Appelbaum: “Lush Life.” Shorter: “Lush Life.” There was some stuff in there. And Shawna(?—0:54) was playing the piano... She was between takes and everything. She was playing...she’s... Appelbaum: She can play. Shorter: Yeah. And tap dancing and all that. But she was like sand-dancing, and waiting for things and all that. I said, “Hey, why don’t you put her in...” Appelbaum: Did Ben Tucker co-write “I’m Comin’ Home, Baby”? Shorter: Ok. He wrote it. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Appelbaum: Oh, yeah? Shorter: Do you remember the mechanicals, “Notice Of Use” thing... There was something about that. -

ISBN-0-9621641-27 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 175P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 526 gA 021 112 AUTHOR Sheffield, Anne, Ed.; 'Frankel, Bruce, Ed. TISLE When I Was Young Loved School: Dropping Out and Hanging In. INSTITUTION Children's Express Foundation, Inc., New York, NY. SPONS AGENCY Primerica Foundation, Greenwich, CT. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9621641-27 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 175p. AVAILABLE FROMMeckler Books, 11 Ferry Lane West, Westport, CT 06880 ($9.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Attitudes; *Dropout Attitudes; Dropout Characteristics; *Dropout Prevention; Dropout Research; Elementary Secondary Education; National Surveys; *Runaways; *Student Attitudes; *Teacher Attitudes; *Youth Programs ABSTRACT Thirteen teenage editors of "Children's Express" investigated the dropout crisis by talking with teenagers who had quit school, with those who had returned to Tive it a second chance (back-to-schoolers), and with others who were iigllting at all odds to hang in there (hangers-in). Hundreds of youth from five American cities -- Newark, Boston, Kansas City, Dallas, and Oakland--were interviewed. Informal and tape-recorded discussions were conducted with groups of students as well as teachers and administrators who were chosen spontaneously. Out of thousands of pages of transcripts, 23 voices were selected to speak for the rest. This book contains five parts concerning respectively: (1) dropouts;(2) runaways; (3) back-to-schoolers; (4) hangers-in; and (5) the beginners, the principal, the teacher, and the young Bronx entrepreneurs. The point of view of the book is that the crisis in the schools is a societal rather than simply an educational issue. -

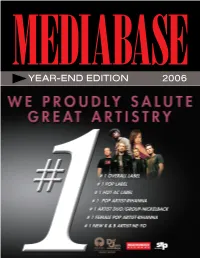

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

1 Below Is a Comprehensive List of All the Lines Hello Barbie Says As O

Below is a comprehensive list of all the lines Hello Barbie says as of November 17, 2015. We are consistently updating and enhancing the product’s vocabulary and will update the lines on this site periodically to reflect any changes. OK, sooooo..... I love hanging out with you! (SIGH) Wow... there's so much we can talk about... I've got a question for you... Oh! I know what we can talk about... Oh, I know what we can do now... Speaking of things you want to be when you grow up... You know what I want to talk about? FRIENDS! So, let's talk friends! Ooh, why don't we talk about friends! Hey... let's talk about friends for a bit! I'm the most myself when I'm around my friends, just playing games and imagining what we'll be when we grow up! You know, I really appreciate my friends who have a completely unique sense of style... like you! You know, on those days where waking up for school is hard, I just think about how much fun it'll be to see my friends. ©2015 Mattel. All Rights Reserved. Version 2 1 You know, talking about all the fun things we do is making me think about who we could do them with ... friends! So we've been talking about family, let's talk about the other people in our lives that mean a lot to us ...like our friends! I bet someone who's a friend to animals knows a thing or two about being a friend to people. -

(Neil Armstrong)That's One Small Step For

1 Sid: Have you lost your impossible dream? My guest has a gift from God to teach you to dream, dream with God and watch those dreams come to pass. Is there a supernatural dimension, a world beyond the one we know? Is there life after death? Do angels exist? Can our dreams contain messages from Heaven? Can we tap into ancient secrets of the supernatural? Are healing miracles real? Sid Roth has spent over 35 years researching the strange world of the supernatural. Join Sid for this edition of It’s Supernatural. Sid: Hello. Sid Roth here. Welcome to my world where it’s naturally supernatural. I want to welcome you here because we have something to impart to you that will change your life. Some of you have lost your vision. Some of you don't even know what it's like to dream with God. You see, God wants to dream with you. God wants you to have a vision for your future, a hope for your future. God wants you to have a vision for your marriage. I know what it looks like right now. But that's not God's best. That's not God's heart. God wants you to have inventions so that you'll be the head and not the tail. And that's not just good proclaiming. That is truth. I pray that you would hear what my guest Leif Hetland has to say. Leif, it was in the year 2000 that you had an encounter with God and he explained about the orphan spirit. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.