Visiting Griffin at the Confluence of Playwriting, Ethics and Spirit: Towards Poet(H)Ic Inquiry in Research-Based Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Studycrux.Com] Golden in Death](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7387/studycrux-com-golden-in-death-217387.webp)

[Studycrux.Com] Golden in Death

Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this St. Martin’s Press ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Time shall unfold what plaited cunning hides: Who cover faults, at last shame them derides. —William Shakespeare ’Tis education forms the common mind; Just as the twig is bent the tree’s inclined. —Alexander Pope Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com 1 Dr. Kent Abner began the day of his death comfortable and content. Following the habit of his day off, he kissed his husband of thirty-seven years off to work, then settled down in his robe with another cup of coffee, a crossword challenge on his PPC, and Mozart’s The Magic Flute on his entertainment unit. His plans for later included a run through Hudson River Park, as April 2061 proved balmy and blooming. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Assistance Series HAROLD M. JONES Interviewed by: Self Initial interview date: n/a Copyright 2002 ADST Dedicated with love and affection to my family, especially to Loretta, my lovable supporting and charming wife ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The inaccuracies in this book might have been enormous without the response of a great number of people I contacted by phone to help with the recall of events, places, and people written about. To all of them I am indebted. Since we did not keep a diary of anything that resembled organized notes of the many happenings, many of our friends responded with vivid memories. I have written about people who have come into our lives and stayed for years or simply for a single visit. More specifically, Carol, our third oldest daughter and now a resident of Boulder, Colorado contributed greatly to the effort with her newly acquired editing skills. The other girls showed varying degrees of interest, and generally endorsed the effort as a good idea but could hardly find time to respond to my request for a statement about their feelings or impressions when they returned to the USA to attend college, seek employment and to live. There is no one I am so indebted to as Karen St. Rossi, a friend of the daughters and whose family we met in Kenya. Thanks to Estrellita, one of our twins, for suggesting that I link up with Karen. “Do you use your computer spelling capacity? And do you know the rule of i before e except after c?” Karen asked after completing the first lot given her for editing. -

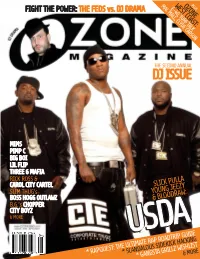

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Big Head, Big Eyes and Big Heart

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2 9 , 2 0 0 8 PAGE 1 3 Big head, big eyes and big heart Blythe tugs at the heartstrings of collectors all over the world, who find creative inspiration in her quirky looks BY CatHerIne SHU STAFF REPORTER cameras snapped, 19 cosplay Blythe is often portrayed as an offbeat competitors made their way fad that has entranced hipsters all around As up and down a runway in a the world. But ask most fans what they like Ximending cafe on Sunday of last week, about their little buddies, and they won’t say inspiring murmurs of appreciation among her collectible value or the fact that she is spectators. Costumes included a buxom trendy. They see Blythe in the same way that Marilyn Monroe, members of the pop group Garan sees her: as a creative muse. S.H.E and Hello Kitty. Each young lady In the seven years since the first neo-Blythe sashayed down the runway, posed and then came out, fans have made photographing, returned — borne aloft in the white-gloved customizing and designing clothing and hands of two event organizers. accessories for her into a mini art movement, This wasn’t your run-of-the-mill contest. displaying their creations on Web sites like All cosplayers were Blythe, the 30cm-tall Flickr and Garan’s ThisIsBlythe.com, and doll with a giant head, big eyes and devoted selling them on eBay, Etsy.com and their own worldwide following. Web sites. Voting was heated, but ultimately Claire “There have been people who have said, Teng’s (鄧淑如) doll prevailed by a wide ‘I was able to quit my day job because I can margin. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

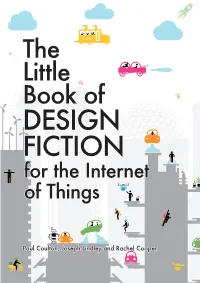

DESIGN FICTION for the Internet of Things

The Li t t tle Bookof DESIGN FICTIONfor the Internet of Things tle Bookof DESIGN FICTIONfor the Internet of Things SCHOOL The Little Book of DESIN FICTION for the Internet Coulton, Lindley and Cooper and Lindley Coulton, Coulton, Lindley and Cooper and Lindley Coulton, of Things Paul Coulton, Joseph Lindley and Rachel Cooper Editor of the PETRAS Little Books series: Dr Claire Coulton ImaginationLancaster, Lancaster University With design by Michael Stead, Roger Whitham and Rachael Hill ImaginationLancaster, Lancaster University ISBN 978-1-86220-346-4 ImaginationLancaster 20 18 All rights reserved. The Little Book of DESIGN FICTION for the Internet of Things Paul Coulton, Joseph Lindley and Rachel Cooper Acknowledgements This book is based on our research conducted for the Acceptability and Adoption theme of the PETRAS Cybersecurity of the Internet of Things Research Hub funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Re- search Council under grant EP/N02334X/1. The aim of PETRAS is to ex- plore critical issues in privacy, ethics, trust, reliability, acceptability, and security and is undertaken by researchers from University College London, Imperial College London, Lancaster University, University of Oxford, Uni- versity of Warwick, Cardiff University, University of Edinburgh, University of Southampton, and the University of Surrey. For their contributions and support in conducting this research and cre- ating this book, many thanks to Claire Coulton, Mike Stead, Haider Ali Akmal, Lidia Facchinello, Richard Lindley, and the team at Imagination Lancaster. Contents C What this little book tells you 4 What is the Internet of Things? 5 What is Design Fiction? 9 Why is Design Fiction for the IoT important? 11 How to build Design Fiction worlds for the IoT 15 Polly: The world’s first truly smart kettle 18 Allspark: Sparking the Internet of Energy 29 Orbit Privacy: Opening doors for the IoT 37 Summary 44 References 45 What this little book tells you This little book is about the future and the Internet of Things (IoT). -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Toys As Tools for Skill-Building and Creativity in Adult Life

Toys as Tools for Skill-building and Creativity in Adult Life Katriina Heljakka School of History, Culture and Arts Studies (Degree Programme of) Cultural Production and Landscape Studies University of Turku E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Previous understandings of adult use of toys are connected with ideas of collecting and hobbying, not playing. This study aims to address toys as play objects employed in imaginative scenarios and as learning devices. This article situates toys (particularly, character toys such as Blythe dolls) as socially shared tools for skill-building and learning in adult life. The interviews with Finnish doll players and analyses of examples of their productive, toy-related play patterns showcased in both offline and digital playscapes reveal how toy play leads to skill-building and creativity at a mature age. The meanings attached to and developed around playthings expand purposely by means of digital and social media. (Audio)visual content- sharing platforms, such as Flickr, Pinterest, Instagram and YouTube, invite mature audiences to join playful dialogues involving mass-produced toys enhanced through do-it-yourself practices. Activities circulated in digital play spaces, such as blogs and photo management applications, demonstrate how adults, as non-professional ‘everyday players’, approach, manipulate and creatively cultivate contemporary playthings. Mature players educate potential players by introducing how to use and develop skills by sharing play patterns associated with their playthings. Producing and broadcasting tutorials on how to play creatively with toys encourage others to build their skills through play. Keywords: Skill-building, creativity, doll, narratives, photoplay, play, social media, toys Introduction In the Western world of the 21st century, toys are everywhere; playthings of all kinds have expanded from the nursery to sites of serious play, public interiors – offices, studios of artists and designers – not to mention the great variety of Seminar.net 2015. -

Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands

June 17, 2013 Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) is set to arrive at the 2013 International Licensing Expo in Las Vegas on June 18 to showcase its global Franchise Brands, including TRANSFORMERS, NERF, MY LITTLE PONY, LITTLEST PET SHOP, PLAY-DOH, MAGIC: THE GATHERING and MONOPOLY. This year's lineup will highlight the company's continued momentum in bringing to market highly innovative brand extensions across key licensing categories such as publishing, digital gaming, apparel and plush, homewares, food, health and beauty. "Hasbro is executing a highly focused and aggressive plan to extend its brand franchises in ways that are engaging for consumers worldwide," said Simon Waters, Senior Vice President, Global Brand Licensing and Publishing at Hasbro. Following are the Hasbro properties that will take center stage at Licensing Expo: TRANSFORMERS Hasbro's iconic TRANSFORMERS brand has become one of the most successful brand franchises of the 21st century and features the heroic AUTOBOTS and the villainous DECEPTICONS engaged in an epic battle on multiple storytelling platforms, including film, television, digital gaming, publishing and theme parks. Hasbro and its licensees provide the avid TRANSFORMERS fan base with high value, age-appropriate merchandise including digital gaming, toys, apparel, sporting goods and more. DeNA and Hasbro recently announced the launch of TRANSFORMERS: LEGENDS, an action card battle game based on the TRANSFORMERS franchise, which is now available on the App Store for iPhone, iPad and iPod touch and on Google Play for Android devices. -

Finding Aid Template

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Corky Steiner Kenner History Collection Finding Aid to the Corky Steiner Kenner History Collection, 1947-1960, 2015 Summary Information Title: Corky Steiner Kenner history collection Creator: Corky Steiner and Joseph L. Steiner (primary) ID: 115.4174 Date: 1947-2015 (inclusive); 1956-1960 (bulk) Extent: 0.75 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English. Abstract: The Corky Steiner Kenner history collection is a compilation of advertisements, instruction manuals, ledgers, financial reports, business letters, journal articles, photographs, DVDs, and other documentation relating to Kenner Products during the 1950s and 1960s. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Corky Steiner Kenner history collection was donated to The Strong in October 2015 as a gift from Corky Steiner. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 115.4174. The materials were received from Corky Steiner, son of Kenner co-founder and Easy-Bake Oven co-creator Joseph L. Steiner, in one box, along with a donation of Kenner trade catalogs and sell sheets. -

Starting Point

Starting Point Education, Outreach, Awareness & Advocacy • March 2018 Offering help, hope, and a voice for people with brain injury and their families Board of Directors Corporate Members Patricia Babin Platinum Chair Charles G. Monnett III & Associates 6842 Morrison Boulevard Charlotte, NC 28211 Wesley Cole 704.376.1911 | www.carolinalaw.com James Cox Bob Dill Martin & Jones, PLLC Martin B. Foil III 410 Glenwood Avenue, Suite 200 Patrick Gallagher Raleigh, NC 27603 Pam Guthrie 919.821.0005 | www.martinandjones.com Thomas Henson Leslie Johnson Neuro Community Care Laurie Leach 853A Durham Road Carol Ornitz Wake Forest, NC 27587 Pier Protz 919.210.5142 | www.neurocc.com Johna Register-Mihalik Gold Mysti Stewart Kris Stroud LearningRx Toby Provoneau 8305 Six Forks Road, Suite 207 Raleigh, NC 27615 Aaron Vaughan 919.232.0090 | www.learningrx.com Silver Hinds’ Feet Farm 14625 Black Farms Road Huntersville, NC 28078 704.992.1424 | www.hindsfeetfarm.org Are you a current member of BIANC? We need your help and your support. Basic Membership: Professional Membership: * $40.00 * $100.00 Perfect for families & survivors! Perfect for professionals interested in making a Includes: difference! Welcome letter from Executive Director Includes all Basic Membership perks and: All BIANC Publications including Starting Point 25% discount all BIANC conferences Membership lapel pin & Membership card ‘Fast Pass’ registration at conference Knowing you are part of the Voice of Brain allowing for Quicker registration Injury and having an impact! Membership Certificate to display *If paid by credit card, membership fee renews annually. Membership may be cancelled at any time. ..Membership dues cannot be prorated.