Botulinum Toxin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real World Efficacy and Tolerability of Acotiamide, in Relieving Meal

testinal & in D o i tr g s e Journal of Gastrointestinal & a s t G i v f e o Narayanan et al., J Gastrointest Dig Syst 2018, 8:1 S l y a s n r ISSN: 2161-069Xt Digestive System DOI: 10.4172/2161-069X.1000553 e u m o J Research Article Open Access Real World Efficacy and Tolerability of Acotiamide, in Relieving Meal- related Symptoms of Functional Dyspepsia Varsha Narayanan*, Amit Bhargava and Shailesh Pallewar 1Department of Medical Services and Research, Lupin Ltd., India *Corresponding author: Narayanan V, Department of Medical Services and Research, Lupin Ltd., Mumbai, India, Tel: +912266402222; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 09, 2018; Accepted date: February 21, 2018; Published date: February 27, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Narayanan V, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Background: Functional Dyspepsia (FD) is a highly prevalent clinical condition that imposes negative economic burden on health-care system as well as greatly impairs quality of life. Treatment of non-specific and bothersome meal-related FD symptoms like post-prandial fullness, upper abdominal bloating and early satiety, is a therapeutic challenge for the clinicians as poorly-defined and ill-understood pathogenesis has hampered efforts to develop effective treatments. Acotiamide is first-in-class drug that exerts its gastro-kinetic effect by enhancing acetylcholine release. Though evidence of its efficacy and tolerance are available through randomized clinical trials, real world data from its regular in-clinic use is lacking. -

Dejong Autman

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): De Jong, S., Vidler, L., Mokrab, Y., Collier, D. A., & Breen, G. D. (Accepted/In press). Gene-set analysis based on the pharmacological profiles of drugs to identify repurposing opportunities in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION α-Bungarotoxin (trifluoroacetate salt) Item No. 16385 Synonyms: α-Bgt, α-BTX Peptide Sequence: IVCHTTATSPISAVTCPPGENLCY Ile Val Cys His Thr Thr Ala Thr Ser Pro RKMWCDAFCSSRGKVVELGCAA Ile Ser Ala Val Thr Cys Pro Pro Gly Glu TCPSKKPYEEVTCCSTDKCNPHP KQRPG, trifluoroacetate salt Asn Leu Cys Tyr Arg Lys Met Trp Cys Asp (Modifications: Disulfide bridge between Ala Phe Cys Ser Ser Arg Gly Lys Val Val 3-23, 16-44, 29-33, 48-59, 60-65) Glu Leu Gly Cys Ala Ala Thr Cys Pro Ser MF: C338H529N97O105S11 • XCF3COOH FW: 7,984.2 Lys Lys Pro Tyr Glu Glu Val Thr Cys Cys Supplied as: A solid Ser Thr Asp Lys Cys Asn Pro His Pro Lys Storage: -20°C Gln Arg Pro Gly Stability: ≥2 years • XCF COOH Solubility: Soluble in aqueous buffers 3 Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures α-Bungarotoxin (trifluoroacetate salt) is supplied as a solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the α-bungarotoxin (trifluoroacetate salt) in water. The solubility of α-bungarotoxin (trifluoroacetate salt) in water is approximately 1 mg/ml. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. Description α-Bungarotoxin is a snake venom-derived toxin that irreversibly binds nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Ki = ~2.5 µM in rat) present in skeletal muscle, blocking action of acetylcholine at the postsynaptic membrane and leading to paralysis.1-3 It has been widely used to characterize activity at the neuromuscular junction, which has numerous applications in neuroscience research.4,5 References 1. -

What Makes Some Bacterial Toxins So Dangerous? the Most Poisonous Substances Known

Features Poisons and antidotes What makes some bacterial toxins so dangerous? The most poisonous substances known David Moss, Ajit Basak We are used to thinking of proteins as beneficial, so it is surprising to realize that the most toxic sub- and Claire Naylor stances known to man are also protein molecules. These are the bacterial exotoxins, proteins secreted (Birkbeck College, London) by pathogenic bacteria. Toxicity is measured by the median lethal dose (LD50). An LD50 value is defined as the mass of toxin per kg of body weight required to wipe out half of an animal population. Whereas Downloaded from http://portlandpress.com/biochemist/article-pdf/32/4/4/5064/bio032040004.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 classic poisons, such as potassium cyanide or arsenic trioxide, have LD50 values in the range 5–15 mg/ kg, the causative agent of botulism, botulinum toxin, has an LD50 in the range 1–3 ng/kg, a million times more toxic! Highly pathogenic toxins have a catalytic ing. Treatment has to be repeated every few months. and a binding domain or subunit In the early 19th Century, it was thought that chol- era was caused by ‘bad air’. It was then discovered that Nearly all of the most potent toxins have two compo- cholera was the result of ingesting faecal-contaminated nents, A and B, that are either separate polypeptide water and we now know that the pathogenic agent is an chains or are separate domains. Component A is an 87 kDa toxin secreted by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae3,4. enzyme which modifies an important protein inside the This bacterium is the cause of many deaths in the de- host cell, whereas B is a protein that enables the toxin veloping world in the aftermath of flooding. -

E30 SEM. O.C. Disclosed Is a Compound Represented by the Formula (1) (51) Int

USOO9453000B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.453,000 B2 Kimura et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Sep. 27, 2016 (54) POLYCYCLIC COMPOUND (56) References Cited (75) Inventors: Teiji Kimura, Tsukuba (JP); Noritaka U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Kitazawa, Tsukuba (JP); Toshihiko 3,470,167 A 9, 1969 Sarkar Kaneko, Tsukuba (JP); Nobuaki Sato, 3,989,816 A 1 1/1976 Rajadhyaksha Tsukuba (JP); Koki Kawano, Tsukuba 4,910,200 A 3, 1990 Curtze et al. (JP): Koichi Ito, Tsukuba (JP); 5,281,626 A 1/1994 Oinuma et al. M s Tak ishi Tsukub JP 5,563,162 A 10, 1996 Oku et al. amoru Takaishi Tsukuba (JP); 5,804,577 A 9, 1998 Hebeisen et al. Takeo Sasaki, Tsukuba (JP); Yu 5,985,856 A 11/1999 Stella et al. Yoshida, Tsukuba (JP); Toshiyuki 6,235,728 B1 5, 2001 Golik et al. Uemura, Tsukuba (JP); Takashi Doko, g R 1939. E. al. Its SE E. Shinmyo, 7,138.414 B2 11/2006 Schoenafingereatch et al. et al. sukuba (JP); Daiju Hasegawa, 7,300,936 B2 11/2007 Parker et al. Tsukuba (JP); Takehiko Miyagawa, 7,314,940 B2 1/2008 Graczyk et al. Hatfield (GB); Hiroaki Hagiwara, 7,618,960 B2 11/2009 Kimura et al. Tsukuba (JP) 7,667,041 B2 2/2010 Kimura et al. 7,687,640 B2 3/2010 Kimura et al. 7,713,993 B2 5/2010 Kimura et al. (73) Assignee: EISAI R&D MANAGEMENT CO., 7,737,141 B2 6/2010 Kimura et al. LTD., Tokyo (JP) 7,880,009 B2 2/2011 Kimura et al. -

PN0496-Acotiamide.Pdf

Acotiamide hydrochloride hydrate (Acofide®) 盐酸阿考替胺 Z-338 in Zeria; YM-443 in Astellas Tablet, oral, EQ 100 mg acotiamide Acotiamide is a peripheral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, indicated for the treatment of functional dyspepsia (FD), which was first-in-class drug to treat FD in the world and approved in 2013 by Japan PMDA. It was originally discovered by Zeria, and co-developed with Astellas. The drug is co-marketing in Japan with a single brand name. The human recommended starting dose is 100 mg at a time, and 3 times a day before meals. Worldwide Key Approvals Global Sales ($Million) Key Substance Patent Expiration 2016-May (US5981557A) 2016-May (EP0870765B1) 2013-Mar (JP) Not available 2021-May (JP3181919B2) 2016-May (CN1063442C) Mechanism of Action Acotiamide hydrochloride hydrate is an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor and enhanced the acetylcholine (ACh)-induced contraction and motility of the gastric antrum and the gastric body. Target Binding Selectivity In vitro Efficacy In vivo Efficacy Mixed pattern: Ki1= 0.61 µM Effect dose of contraction in gastric sample: Significantly improved the gastrointestinal motility: Ki2= 2.7 µM ACh-induced: at 1 µM In normal and gastric hypomotility dogs: at 10 mg/kg. Inhibition: IC50= 3 µM Electrical-induced: at 0.3 µM In gastric hypomotility rats: at 100 mg/kg. Pharmacokinetics Parameters Rats Dogs Healthy Humans 3 10 3 10 50 mg 100 mg 200 mg 400 mg 800 mg Dose (mg/kg) (i.v.) (p.o.) (i.v.) (p.o.) (p.o.) (p.o.) (p.o.) (p.o.) (p.o.) Tmax (hr) - 0.08 - 0.5 2.75 2.42 2.08 2.25 2.13 Cmax -

Arecoline Promotes Migration of A549 Lung Cancer Cells Through Activating the EGFR/Src/FAK Pathway

toxins Article Arecoline Promotes Migration of A549 Lung Cancer Cells through Activating the EGFR/Src/FAK Pathway Chih-Hsiang Chang 1,†, Mei-Chih Chen 2,3,†, Te-Huan Chiu 1 , Yu-Hsuan Li 1, Wan-Chen Yu 1, Wan-Ling Liao 1, Muhammet Oner 1, Chang-Tze Ricky Yu 4, Chun-Chi Wu 5, Tsung-Ying Yang 6, Chieh-Lin Jerry Teng 7, Kun-Yuan Chiu 8, Kun-Chien Chen 6, Hsin-Yi Wang 9, Chia-Herng Yue 10, Chih-Ho Lai 11 , Jer-Tsong Hsieh 12 and Ho Lin 1,13,14,* 1 Department of Life Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 40227, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-H.C.); [email protected] (T.-H.C.); [email protected] (Y.-H.L.); [email protected] (W.-C.Y.); [email protected] (W.-L.L.); [email protected] (M.O.) 2 Medical Center for Exosomes and Mitochondria Related Diseases, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40447, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Nursing, Asia University, Taichung 41345, Taiwan 4 Department of Applied Chemistry, National Chi Nan University, Nantou 54561, Taiwan; [email protected] 5 Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 40201, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Division of Chest Medicine, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung 40705, Taiwan; [email protected] (T.-Y.Y.); [email protected] (K.-C.C.) 7 Division of Hematology/Medical Oncology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung 40705, Taiwan; [email protected] 8 Division of Urology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung 40705, Taiwan; [email protected] 9 Department of Nuclear Medicine, Taichung -

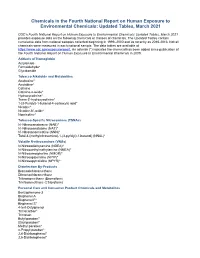

Chemicals in the Fourth Report and Updated Tables Pdf Icon[PDF

Chemicals in the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 CDC’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 provides exposure data on the following chemicals or classes of chemicals. The Updated Tables contain cumulative data from national samples collected beginning in 1999–2000 and as recently as 2015-2016. Not all chemicals were measured in each national sample. The data tables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. An asterisk (*) indicates the chemical has been added since publication of the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in 2009. Adducts of Hemoglobin Acrylamide Formaldehyde* Glycidamide Tobacco Alkaloids and Metabolites Anabasine* Anatabine* Cotinine Cotinine-n-oxide* Hydroxycotinine* Trans-3’-hydroxycotinine* 1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-butanol-4-carboxylic acid* Nicotine* Nicotine-N’-oxide* Nornicotine* Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) N’-Nitrosoanabasine (NAB)* N’-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT)* N’-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN)* Total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol) (NNAL)* Volatile N-nitrosamines (VNAs) N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)* N-Nitrosoethylmethylamine (NMEA)* N-Nitrosomorpholine (NMOR)* N-Nitrosopiperidine (NPIP)* N-Nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR)* Disinfection By-Products Bromodichloromethane Dibromochloromethane Tribromomethane (Bromoform) Trichloromethane (Chloroform) Personal Care and Consumer Product Chemicals and Metabolites Benzophenone-3 Bisphenol A Bisphenol F* Bisphenol -

Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Nicotine Pharmacology and Dependence

Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Nicotine Pharmacology and Dependence Christie D. Fowler, Jill R. Turner, and M. Imad Damaj Contents 1 Introduction 2 Basic Neurocircuitry of Nicotine Addiction 3 Role of Nicotinic Receptors in Nicotine Dependence and Brain Function 4 Modulatory Factors That Influence nAChR Expression and Signaling 5 Genomics and Genetics of Nicotine Dependence 5.1 Overview 5.2 Human and Animal Genetic Studies 5.3 Transcriptionally Adaptive Changes 6 Other Constituents in Nicotine and Tobacco Products Mediating Dependence 7 Therapeutic Approaches for Tobacco and Nicotine Dependence 7.1 Nicotine Replacement Therapies 7.2 Varenicline and Bupropion 7.3 Novel Approaches 8 Conclusion References Abstract Tobacco dependence is a leading cause of preventable disease and death world- wide. Nicotine, the main psychoactive component in tobacco cigarettes, has also C. D. Fowler Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA J. R. Turner Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA M. Imad Damaj (*) Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA Translational Research Initiative for Pain and Neuropathy at VCU, Richmond, VA, USA e-mail: [email protected] # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2019_252 C. D. Fowler et al. been garnering increased popularity in its vaporized form, as derived from e-cigarette devices. Thus, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms under- lying nicotine pharmacology and dependence is required to ascertain novel approaches to treat drug dependence. In this chapter, we review the field’s current understanding of nicotine’s actions in the brain, the neurocircuitry underlying drug dependence, factors that modulate the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, and the role of specific genes in mitigating the vulnerability to develop nicotine dependence. -

Upregulation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Α And

Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer Chih-Yang Wang, Ying-Jui Chao, Yi-Ling Chen, Tzu-Wen Wang, Nam Nhut Phan, Hui-Ping Hsu, Yan-Shen Shan, Ming-Derg Lai 1 Supplementary Table 1. Demographics and clinical outcomes of five patients with ampullary cancer Time of Tumor Time to Age Differentia survival/ Sex Staging size Morphology Recurrence recurrence Condition (years) tion expired (cm) (months) (months) T2N0, 51 F 211 Polypoid Unknown No -- Survived 193 stage Ib T2N0, 2.41.5 58 F Mixed Good Yes 14 Expired 17 stage Ib 0.6 T3N0, 4.53.5 68 M Polypoid Good No -- Survived 162 stage IIA 1.2 T3N0, 66 M 110.8 Ulcerative Good Yes 64 Expired 227 stage IIA T3N0, 60 M 21.81 Mixed Moderate Yes 5.6 Expired 16.7 stage IIA 2 Supplementary Table 2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of an ampullary cancer microarray using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). This table contains only pathways with p values that ranged 0.0001~0.05. KEGG Pathway p value Genes Pentose and 1.50E-04 UGT1A6, CRYL1, UGT1A8, AKR1B1, UGT2B11, UGT2A3, glucuronate UGT2B10, UGT2B7, XYLB interconversions Drug metabolism 1.63E-04 CYP3A4, XDH, UGT1A6, CYP3A5, CES2, CYP3A7, UGT1A8, NAT2, UGT2B11, DPYD, UGT2A3, UGT2B10, UGT2B7 Maturity-onset 2.43E-04 HNF1A, HNF4A, SLC2A2, PKLR, NEUROD1, HNF4G, diabetes of the PDX1, NR5A2, NKX2-2 young Starch and sucrose 6.03E-04 GBA3, UGT1A6, G6PC, UGT1A8, ENPP3, MGAM, SI, metabolism -

Biological Toxins As the Potential Tools for Bioterrorism

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Biological Toxins as the Potential Tools for Bioterrorism Edyta Janik 1, Michal Ceremuga 2, Joanna Saluk-Bijak 1 and Michal Bijak 1,* 1 Department of General Biochemistry, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Pomorska 141/143, 90-236 Lodz, Poland; [email protected] (E.J.); [email protected] (J.S.-B.) 2 CBRN Reconnaissance and Decontamination Department, Military Institute of Chemistry and Radiometry, Antoniego Chrusciela “Montera” 105, 00-910 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +48-(0)426354336 Received: 3 February 2019; Accepted: 3 March 2019; Published: 8 March 2019 Abstract: Biological toxins are a heterogeneous group produced by living organisms. One dictionary defines them as “Chemicals produced by living organisms that have toxic properties for another organism”. Toxins are very attractive to terrorists for use in acts of bioterrorism. The first reason is that many biological toxins can be obtained very easily. Simple bacterial culturing systems and extraction equipment dedicated to plant toxins are cheap and easily available, and can even be constructed at home. Many toxins affect the nervous systems of mammals by interfering with the transmission of nerve impulses, which gives them their high potential in bioterrorist attacks. Others are responsible for blockage of main cellular metabolism, causing cellular death. Moreover, most toxins act very quickly and are lethal in low doses (LD50 < 25 mg/kg), which are very often lower than chemical warfare agents. For these reasons we decided to prepare this review paper which main aim is to present the high potential of biological toxins as factors of bioterrorism describing the general characteristics, mechanisms of action and treatment of most potent biological toxins. -

Nicotinic Receptors in Neurodegeneration

Send Orders of Reprints at [email protected] 298 Current Neuropharmacology, 2013, 11, 298-314 Nicotinic Receptors in Neurodegeneration Inmaculada Posadas, Beatriz López-Hernández and Valentín Ceña* Unidad Asociada Neurodeath. CSIC-Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Departamento de Ciencias Médicas. Albacete, Spain and CIBERNED, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain Abstract: Many studies have focused on expanding our knowledge of the structure and diversity of peripheral and central nicotinic receptors. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are members of the Cys-loop superfamily of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels, which include GABA (A and C), serotonin, and glycine receptors. Currently, 9 alpha (2-10) and 3 beta (2-4) subunits have been identified in the central nervous system (CNS), and these subunits assemble to form a variety of functional nAChRs. The pentameric combination of several alpha and beta subunits leads to a great number of nicotinic receptors that vary in their properties, including their sensitivity to nicotine, permeability to calcium and propensity to desensitize. In the CNS, nAChRs play crucial roles in modulating presynaptic, postsynaptic, and extrasynaptic signaling, and have been found to be involved in a complex range of CNS disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), schizophrenia, Tourette´s syndrome, anxiety, depression and epilepsy. Therefore, there is growing interest in the development of drugs that modulate nAChR functions with optimal benefits and minimal adverse effects. The present review describes the main characteristics of nAChRs in the CNS and focuses on the various compounds that have been tested and are currently in phase I and phase II trials for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases including PD, AD and age-associated memory and mild cognitive impairment.