What Is “Academic” Writing? by L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Quick Guide to Scholarly Publishing

A QUICK GUIDE TO SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING GRADUATE WRITING CENTER • GRADUATE DIVISION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY Belcher, Wendy Laura. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2009. Benson, Philippa J., and Susan C. Silver. What Editors Want: An Author’s Guide to Scientific Journal Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. Derricourt, Robin. An Author’s Guide to Scholarly Publishing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. Germano, William. From Dissertation to Book. 2nd ed. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. ———. Getting It Published: A Guide for Scholars and Anyone Else Serious about Serious Books. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Goldbort, Robert. Writing for Science. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2006. Harman, Eleanor, Ian Montagnes, Siobhan McMenemy, and Chris Bucci, eds. The Thesis and the Book: A Guide for First- Time Academic Authors. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. Harmon, Joseph E., and Alan G. Gross. The Craft of Scientific Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. Huff, Anne Sigismund. Writing for Scholarly Publication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1999. Luey, Beth. Handbook for Academic Authors. 5th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Luey, Beth, ed. Revising Your Dissertation: Advice from Leading Editors. Updated ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. Matthews, Janice R., John M. Bowen, and Robert W. Matthews. Successful Scientific Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide for the Biological and Medical Sciences. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008. Moxley, Joseph M. PUBLISH, Don’t Perish: The Scholar’s Guide to Academic Writing and Publishing. -

Using a Survey of Writing Assignments to Make Informed Curricular Decisions

WPA: Writing Program Administration, Volume 8, Number 3, Spring 1985 © Council of Writing Program Administrators Using a Survey of Writing Assignments to Make Informed Curricular Decisions Jeanette Harris and Christine Hult Because almost every member of an English department teaches fresh man composition, all too often the course is shaped by the diverse theories and inclinations of those who teach it. Many English faculty, especially those trained in literature, still believe that freshman composi tion should teach students how to read and write about literature. Others see its purpose as teaching students to write about themselves. Still others insist that freshman composition should give students tradi tional instruction in the rhetorical modes. But increasing numbers are convinced that freshman composition, if it is to survive as part of a college's or university's core curriculum, must prepare students for majors in other disciplines. In fact, the academic community accepts the usual composition requirement because it assumes we are providing students with generally useful writing skills-not only those that stu dents need in their academic lives but also those they will later need in their professional lives. In order to discover the writing skills needed by students, we must move beyond the confines of our own discipline and into the academic community at large. Although much has been written about our obliga tion to extend writing instruction across the curriculum, very little attention has been given to an equally important obligation; our respon sibility to incorporate the writing assignments of other disciplines into ourown curricula. As Arthur M. Eastman suggested in a paper presented at the 1981 annual meeting of the Modern Language Association, our mission to teach literacy is two-fold. -

Publishing and Academic Writing: Experiences of Authors Who Have

Publishing and Academic Writing: Experiences of Authors Who Have Published in PROFILE*1 Publicación y escritura académica: experiencias de autores que han publicado en PROFILE Melba L. Cárdenas2** Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia The increase in the publication of academic journals is closely related to the growing interest of re- search communities as well as of institutional policies that demand visibility of the work done by their staff through publications in highly-ranked journals. The purpose of this paper is to portray the experi- ences of some authors who published their articles in the PROFILE journal, which is edited in Colombia, South America. Data were gathered using a survey carried out through the use of a questionnaire. The results indicate the reasons the authors submitted their manuscripts, their experiences along the process of publication, and what the publication of their articles in the journal has meant to them. The authors’ responses and the reflections derived from them also show that despite the difficulties faced, there were achievements and lessons learned as well as challenges ahead to ensure the sustainability of the journal and teachers’ empowerment. Key words: Academic journals, getting published, PROFILE Journal, publishing articles, teachers as writers. El aumento de la publicación de artículos en revistas académicas está relacionado con el creciente interés en ello por parte de los grupos de investigación, así como con las políticas institucionales que buscan dar mayor visibilidad a sus trabajos. El objetivo de este artículo es recoger las experiencias de algunos autores que publicaron en la revista PROFILE, editada en Colombia, Sur América. -

Buying In, Selling Short: a Pedagogy Against the Rhetoric of Online Paper Mills

Buying In, Selling Short: A Pedagogy against the Rhetoric of Online Paper Mills Kelly Ritter I don’t cheat, but not because it is unacceptable. I don’t cheat because I’m picky about my work and would never use someone else’s, especially if they didn’t write as well as me. — English 101 student Unlike other forms of academic dishonesty, which are driven only by the desire for a reward or at least the pursuit of a discrete “right” answer, pla- giarism is additionally, and importantly, reliant on students’ perceptions of authorship. The purchase of essays from paper mill Web sites, as one of the more egregious forms of plagiarism, is generally undertheorized in English studies, perhaps because it is often viewed as a less complicated problem in the context of larger, more “forgivable” acts such as the visible rise of cut and paste and other types of academic dishonesty at the postsecondary level. Clearly, however, the advent of digital technologies that allow access to completed papers on a variety of topics, often at a low price or at no cost and delivered instantly to one’s e-mail inbox, has created valid concern among faculty, especially those involved in the teaching of writing.1 This concern has generated a great amount of discussion about detecting such wholesale (and frequently labeled as criminal) plagiarism, diverting attention away from Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture Volume 6, Number 1, © 2006 Duke University Press 25 the more productive discussion of how faculty might prevent such plagiarism from occurring in the first place. -

Hermeneutics: a Literary Interpretive Art

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretive Art David A. Reitman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3403 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] HERMENEUTICS: A LITERARY INTERPRETATIVE ART by DAVID A. REITMAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 DAVID A. REITMAN All Rights Reserved ii Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretative Art by David A. Reitman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date George Fragopoulos Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretative Art by David A. Reitman Advisor: George Fragopoulos This thesis examines the historical traditions of hermeneutics and its potential to enhance the process of literary interpretation and understanding. The discussion draws from the historical emplotment of hermeneutics as literary theory and method presented in the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism with further elaboration from several other texts. The central aim of the thesis is to illuminate the challenges inherent in the literary interpretive arts by investigating select philosophical and linguistic approaches to the study and practice of literary theory and criticism embodied within the canonical works of the Anthology. -

Grammar for Academic Writing

GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Tony Lynch and Kenneth Anderson (revised & updated by Anthony Elloway) © 2013 English Language Teaching Centre University of Edinburgh GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Contents Unit 1 PACKAGING INFORMATION 1 Punctuation 1 Grammatical construction of the sentence 2 Types of clause 3 Grammar: rules and resources 4 Ways of packaging information in sentences 5 Linking markers 6 Relative clauses 8 Paragraphing 9 Extended Writing Task (Task 1.13 or 1.14) 11 Study Notes on Unit 12 Unit 2 INFORMATION SEQUENCE: Describing 16 Ordering the information 16 Describing a system 20 Describing procedures 21 A general procedure 22 Describing causal relationships 22 Extended Writing Task (Task 2.7 or 2.8 or 2.9 or 2.11) 24 Study Notes on Unit 25 Unit 3 INDIRECTNESS: Making requests 27 Written requests 28 Would 30 The language of requests 33 Expressing a problem 34 Extended Writing Task (Task 3.11 or 3.12) 35 Study Notes on Unit 36 Unit 4 THE FUTURE: Predicting and proposing 40 Verb forms 40 Will and Going to in speech and writing 43 Verbs of intention 44 Non-verb forms 45 Extended Writing Task (Task 4.10 or 4.11) 46 Study Notes on Unit 47 ii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Unit 5 THE PAST: Reporting 49 Past versus Present 50 Past versus Present Perfect 51 Past versus Past Perfect 54 Reported speech 56 Extended Writing Task (Task 5.11 or 5.12) 59 Study Notes on Unit 60 Unit 6 BEING CONCISE: Using nouns and adverbs 64 Packaging ideas: clauses and noun phrases 65 Compressing noun phrases 68 ‘Summarising’ nouns 71 Extended Writing Task (Task 6.13) 73 Study Notes on Unit 74 Unit 7 SPECULATING: Conditionals and modals 77 Drawing conclusions 77 Modal verbs 78 Would 79 Alternative conditionals 80 Speculating about the past 81 Would have 83 Making recommendations 84 Extended Writing Task (Task 7.13) 86 Study Notes on Unit 87 iii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Introduction Grammar for Academic Writing provides a selective overview of the key areas of English grammar that you need to master, in order to express yourself correctly and appropriately in academic writing. -

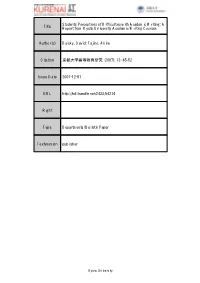

A Report from Kyoto University Academic Writing Courses Autho

Students' Perceptions of Difficulties with Academic Writing: A Title Report from Kyoto University Academic Writing Courses Author(s) Dalsky, David; Tajino, Akira Citation 京都大学高等教育研究 (2007), 13: 45-52 Issue Date 2007-12-01 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/54214 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学高等教育研究第13 号 (2007) Students'Perceptions Students'Perceptions of Difficulties with Academic Writing: A Report from Kyoto University Academic Writing Courses David Dalsky (Graduate (Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University) Akira Tajino (Center (Center for the Promotion of Excellence in Higher Education, Kyoto University) Summary Academic writing is one of the keys to success in students'academic lives, yet one of the most difficult skills to learn. learn. In 2006, Kyoto University adopted a new English curriculum in Liberal Arts and General Education requiring all first-year first-year and second-year students to enroll in academic English courses. This paper aims to identify and report the difficulties difficulties students face in the process of academic writing in their transition from high school to their first and second year year at the university. The study discussed in this paper was conducted in two first-year academic writing courses and one second-year academic writing course at Kyoto University in spring 2007. At the end of the term, the students completed completed a survey about their perceptions of difficulties with the content of the course. The first-year students reported most difficulty with adapting to the transition from high school practical English (English for General Purposes) to university university academic English (English for Academic Purposes), especially with writing in a formal style and thinking about about the rules of academic writing. -

The First Person in Academic Writing

The First Person in Academic Writing Because I Said So: Effective Use of the First-Person Perspective and the Personal Voice in Academic Writing Whether working within scientific disciplines, the social sciences, or the humanities, writers often struggle with how to infuse academic material with a unique, personal “voice.” Many writers have been told by teachers not to use the first-person perspective (indicated by words such as I, we, my, and our) when writing academic papers. However, in certain rhetorical situations, self-references can strengthen our argument and clarify our perspective. Depending on the genre and discipline of the academic paper, there may be some common conventions for use of the first person that the writer should observe. Developing a personal voice within an academic paper involves much more than simply mentioning yourself. Writing in a personal voice can mean using language that comes naturally, allowing the writer to clearly express personal opinions or emotions on a subject. One simple test for your work is to read it aloud and then ask yourself, “Does this sound like something I would really say?” Writing in an overly emotional style can detract from an argument’s logical or ethical appeals. On the other hand, writing that omits personal or emotional content often results in less compelling statements, and it may appear to straddle issues indecisively rather than staking a strong claim. As one Duke undergraduate observes, “the lack of a personal voice” can indicate “a lack of ownership over ideas and arguments,” which is crucial to successful academic writing (Knox 3). -

Writing a Literature Review Writing Centre Learning Guide

Writing a Literature Review Writing Centre Learning Guide At some point in your university study, you may be asked to review the literature on a certain subject or in a particular area. Such a review involves comparing different writers’ ideas or perspectives on a topic and evaluating these ideas, all in relation to your own work. A literature review differs from an article review in that it involves writing about several writers’ ideas, rather than evaluating a single article. It is also different to an annotated bibliography, which is usually a series of short reflections on individual pieces of writing. Introduction The literature review enables you and your reader to get an overview of a certain subject, so that it is clear who the main writers are in the field, and which main points need to be addressed. It should be an evaluative piece of writing, rather than just a description. This means that you need to weigh up arguments and critique ideas, rather than just providing a list of what different writers have said. It is up to you to decide what the reader needs to know on the topic, but you should only include the main pieces of writing in this area; a literature review does not need to include everything ever written on the topic. The most important thing is to show how the literature relates to your own work. You may be writing a literature review as part of a thesis, or as an exercise in itself. Whatever the reason, there are many benefits to writing a literature review. -

Harnessing Bibliometric Measures for a Scholarly Paper Recommender System

BIR 2018 Workshop on Bibliometric-enhanced Information Retrieval BIBLME RecSys: Harnessing Bibliometric Measures for a Scholarly Paper Recommender System Ana¨ısOllagnier, S´ebastien Fournier, and Patrice Bellot Aix Marseille Univ, Toulon University, CNRS, LIS, Marseille, France {anais.ollagnier,sebastien.fournier,patrice.bellot}@univ-amu.fr Abstract. The iterative continuum of scientific production generates a need for filtering and specific crossing of ideas and papers. In this paper, we present BIBLME RecSys software which is dedicated to the analysis of bibliographical references extracted from scientific collections of papers. Our goal is to provide users with paper suggestions guided by the papers they are reading and by the references they contain. To do so, we propose a new approach based on a new bibliometric measure. We propose to determine the impact, the inner representativeness, of each bibliographical reference according to their occurrences in the paper the user is reading. By means of this approach, we suggest central references of the author's paper. As a result, we obtain papers that are related to the paper selected by the user according to the influence of references on it. We evaluate the recommendation in the context of a digital library dedicated to humanities and social sciences. Keywords: Recommender systems, Text mining, Digital libraries, Bib- liographic information, Bibliometrics. 1 Introduction There are 114 million of scholarly papers archived on the Web [9]. While cer- tainly advantageous, researchers have unprecedented level of access which creates a problem of \information overload" [2]. To help generate relevant suggestions for researchers, scholarly paper recommenders emerged over the last decade to ease finding publications. -

6. Hermeneutic Writing

STEPHEN LOFTUS AND FRANZISKA TREDE 6. HERMENEUTIC WRITING HERMENEUTICS AND INTERPRETATION Hermeneutic writing is the art of transforming interpretations, meanings and arguments into words for the benefit of others and for oneself. Writing down our interpretations can be seen as an integral part of the hermeneutic process. When we attempt to express our interpretations in written form we may find that the very attempt to do so invites us to think more deeply about those same interpretations. It is not uncommon to discover that by trying to articulate and communicate our interpretations we realise that our understanding of a phenomenon is not as well formed as we first thought it was, prompting us to take a step back and think again, and think more deeply. Features of hermeneutic writing include adding meaning, making connections clearer and articulating a depth of understanding. Deeper understanding can lead to further revelations and insights. We cannot write without bias but we can learn to understand and manage our biases more critically. Hermeneutic writing makes explicit and transparent how we think, argue, and make sense of the world. Hermeneutic writing is a dialogical activity between the writer, the phenomenon being explored and the potential audience. The driving force behind hermeneutic writing is the need to understand better and more profoundly. It can be argued that all forms of research, qualitative and quantitative, involve interpretation of some kind. Researchers are expected to generate new knowledge through processing various forms of empirical data (including both sense and experiential data). In empirico-analytical approaches to research, data is collected and analysed and results are presented, whereas in a hermeneutic approach texts are constructed, interpreted, and findings are written up. -

Academic Writing Infographic

What is Academic Writing? Academic writing is a style of writing that is objective, unbiased, and focuses on supporting information with reliable and credible data and evidence. Academic writing is geared toward contributing to the body of knowledge on a topic or field of study. Purpose Audience Tone Examples To contribute to the Scholars, researchers, Professional, Research paper, peer- field of knowledge and practitioners unbiased, formal reviewed journal article, on a topic. within the field of (not conversational), textbook, lab report, study. unemotional. literature review. Why Academic Writing? An academic writing style is used because it presents scholarly information with an unbiased and credible approach that is expected in scholarly writing. The style and tone of academic writing is followed in order to create a professional, trustworthy piece that is free from bias and works to contribute to the body of knowledge on a topic. How is Academic Writing Different From Professional Writing? Format of Professional Writing Format of Academic Writing • Typically no title page • Academic style guide is used • Bulleted lists are often used (such as MLA or APA) • Use of bold font or italics for • Conventional paragraph structure emphasis with minimal use of bullet points • Tables or charts commonly used • Consistent font used throughout • List of resources not typically with no use of bold or italics other included than section headings • Often single-spaced • In-text citations and list of resources (e.g. memos, PowerPoints, reports, emails) always included • Double-spaced Style of Professional Writing Style of Academic Writing • Avoids discipline-specific jargon • Discipline-specific jargon is used • Seldom use of research • Scholarly sources are always included • Uses first person point of view • Uses third person point of view • The purpose is stated directly • Avoids "I" statements (e.g.