Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American International Pictures Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary •JO NO. 47 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL PICTURES RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART The Department of Film of The Museum of Modern Art will present a retrospective exhibition of films from American International Pictures beginning July 26 and running through August 28, 1979. The 38 film retrospective, which coincides with the studio's 25th anniversary, was selected from the company's total production of more than 500 films, by Adrienne Mancia, Curator, and Larry Kardish, Associate Curator, of the Museum's Department of Film. The films, many in new 35mm prints, will be screened in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium and, concurrent with the retro spective, a special installation of related film stills and posters will be on view in the adjacent Auditorium Gallery. "It's extraordinary to see how many filmmakers, writers and actors — now often referred to as 'the New Hollywood'—took their first creative steps at American International," commented Adrienne Mancia. "AIP was a good training ground; you had to work quickly and economically. Low budgets can force you to find fresh resources. There is a vitality and energy to these feisty films that capture a certain very American quality. I think these films are rich in information about our popular culture and we are delighted to have an opportunity to screen them." (more) II West 53 Street, New York, NY. 10019, 212-956-6100 Coble: Modernart NO. 47 Page 2 Represented in the retrospective are Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Jack Nicholson, Annette Funicello, Peter Fonda, Richard Dreyfuss, Roger Corman, Ralph Bakshi, Brian De Palma, John Milius, Larry Cohen, Michael Schultz, Dennis Hopper, Michelle Phillips, Robert De Niro, Bruce Dern, Michael Landon, Charles Bronson, Mike Curb, Richard Rush, Tom Laughlin, Cher, Richard Pryor, and Christopher Jones. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Teenage Flicks

TEENAGE FLICKS Week 1: From Clean Cut Kids to Delinquents - Post War Depictions of Adolescence – the Emergence of the Teen. The Guinea Pig (1948) Roy Boulting • Directed by Roy Boulting • Produced by John Boulting • Written by Roy Boulting and Bernard Miles • Based on the play by Warren Chetham-Strode • Cinematography by Gilbert Taylor • Edited by Richard Best • Music by John Wooldridge • Though Attenborough was playing a fourteen-year-old, he was actually twenty-five at the time • The film was largely financed by a ‘mystery industrialist’ • Whereas later British films about young worKing class adults embodied a healthy form of rebellion, this film seems to do the opposite, inferring that the only way for worKing class people to ‘get on’ is to take advantage of opportunities dealt out to them by the upper echelons • The film was inspired by the changes brought about by The Fleming Report • The Education Act 1944 offered a new status to endowed grammar schools receiving a grant from central government. • The grammar schools would receive partial state funding in return for taking between 25 and 50 percent of its pupils from state primary schools • The Fleming Committee recommended that one-quarter of the places at public schools should be assigned to a national bursary scheme for children who would benefit from boarding. • JacK Read (Attenborough) gains a scholarship at a public boarding school as part of a post war experiment • While at the school JacK is faced with snobbery and bullying • After much hardship, JacK is able to ’fit in’ -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

For More Than Seventy Years the Horror Film Has

WE BELONG DEAD FEARBOOK Covers by David Brooks Inside Back Cover ‘Bride of McNaughtonstein’ starring Eric McNaughton & Oxana Timanovskaya! by Woody Welch Published by Buzzy-Krotik Productions All artwork and articles are copyright their authors. Articles and artwork always welcome on horror fi lms from the silents to the 1970’s. Editor Eric McNaughton Design and Layout Steve Kirkham - Tree Frog Communication 01245 445377 Typeset by Oxana Timanovskaya Printed by Sussex Print Services, Seaford We Belong Dead 28 Rugby Road, Brighton. BN1 6EB. East Sussex. UK [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/106038226186628/ We are such stuff as dreams are made of. Contributors to the Fearbook: Darrell Buxton * Darren Allison * Daniel Auty * Gary Sherratt Neil Ogley * Garry McKenzie * Tim Greaves * Dan Gale * David Whitehead Andy Giblin * David Brooks * Gary Holmes * Neil Barrow Artwork by Dave Brooks * Woody Welch * Richard Williams Photos/Illustrations Courtesy of Steve Kirkham This issue is dedicated to all the wonderful artists and writers, past and present, that make We Belong Dead the fantastic magazine it now is. As I started to trawl through those back issues to chose the articles I soon realised that even with 120 pages there wasn’t going to be enough room to include everything. I have Welcome... tried to select an ecleectic mix of articles, some in depth, some short capsules; some serious, some silly. am delighted to welcome all you fans of the classic age of horror It was a hard decision as to what to include and inevitably some wonderful to this first ever We Belong Dead Fearbook! Since its return pieces had to be left out - Neil I from the dead in March 2013, after an absence of some Ogley’s look at the career 16 years, WBD has proved very popular with fans. -

Zapf.Punkt 2

Summer Solstice 201 9 ein Schlag ins Gesicht des Weltraums Zapf.punkt 2 Italian Horror Castles - Situationism - Jekyll & Hyde zapf.punkt jun 2019 Table of Contents 2 Castle to Castle in Italian Horror 9 On Situationism: An Interview 16 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1 886) 20 A Tragedy of Errors at Notre Dame cover: Margrete Robsahm from Castle of Blood, and background cutout by Roy Gold. Collage: Lex Berman, contents banner: Barbara Steele in Black Sunday (1 962), back cover: Collage: Lex Berman. Zapf.Punkt Quarterly, V.1 No.2, (Jun 2019) is published by Diamond Bay Press, PO Box 426028, Cambridge, MA, 02142. Editor: Lex Berman. Entire contents (c) 2019 by Merrick Lex Berman. All rights are herewith released to individual contributors. Nothing may be reproduced or otherwise distributed without their permission. Please send articles and LOC to [email protected] zapf.punkt page 2 half an hour into the film, when told directly to his face that there is a Zapf.pweurewolf onnthe looske, he cant't believe it. ein Schlag ins Gesicht desGyWpsye: lIt'lrl taelul ymou swhat a werewolfis: it's a human being possessed by a wolf! Quantum Physics - CthulWhhuen t-he eDvil heyeairs aonnyoiu,Cthue slavtasge Barbara Steele at Massimo Castle, Arsoli, Italy, from La beast somehow gets inside and controls Maschera del Demonio (1960) you. Makes you look and act like a wolf. Castle to Castle Makes you hunt down a victim and kill like a wolf. With fangs: like a wolf! in Italian Horror Cop: Why you're crazy! You better not My introduction to horror movies was let anyone hear you talk like that Pappy, or at the Saturday matinee in Chicago. -

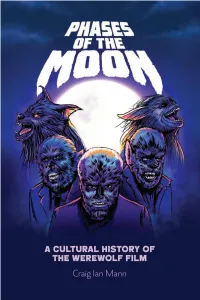

Phases of the Moon

Phases of the Moon 66535_MANN.indd535_MANN.indd i 114/09/204/09/20 111:511:51 AAMM 66535_MANN.indd535_MANN.indd iiii 114/09/204/09/20 111:511:51 AAMM Phases of the Moon A Cultural History of the Werewolf Film Craig Ian Mann 66535_MANN.indd535_MANN.indd iiiiii 114/09/204/09/20 111:511:51 AAMM For the Monster Squad Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Craig Ian Mann, 2020 © Foreword, Stacey Abbott, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 4111 7 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 4113 1 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 4114 8 (epub) The right of Craig Ian Mann to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders for the images that appear in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. -

Jeepers Creepers: Great Songs from Horror Films

Jeepers Creepers: Great Songs from Horror Films A LITTLE NIGHTMARE MUSIC the film’s advertising campaign featured an image of score, using one of Jimmy Van Heusen’s lilting mel- the dead Reynolds, garishly dressed in a bloodied “tin odies for the three songs intended for top billed Pat For an album of tuneful melodies from movies that soldier” dance costume, in tandem with the Johnny Boone. The song itself--”The Faithful Heart,” sung by sometimes took a week or less to make, JEEPERS Mercer lyric, “So you met someone and now you know Boone on a makeshift raft in the center of an under- CREEPERS: GREAT SONGS FROM HORROR how it feels.” Effective, certainly, but as Harrington was ground sea--wound up on the cutting room floor, as FILMS was certainly a long time coming. quick to point out, it gave away the end of the picture! did “Twice as Tall.” (Only “My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose,” for which Van Heusen set Robert Burns’ poem It was some 10 years ago, at a New York book and 3. LOOK FOR A STAR. Some years before he wrote to music, made the final cut.) magazine show, that Scarlet Street magazine manag- a seemingly endless string of Top Ten hits for Petu- Tom Amorosi initially argued against including ing editor Tom Amorosi and I met the multi-talented la Clark (“Downtown,” “I Know a Place,” “Colour My “The Faithful Heart” in this collection, since JOUR- Bruce Kimmel for the first time. A few weeks later, World,” “Don’t Sleep in the Subway”), Tony Hatch, NEY isn’t strictly a horror film. -

SCIENCE FICTION CYCLES EARLY Late 20'S/30'S 40'S

SCIENCE FICTION CYCLES EARLY Le Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902) French The Golem (1915) Star Prince (1918) How to Make Time Fly (1905) Mechanical Statue and the Ingenious Servant, The (1907) Frankenstein –(1910) US Homunculus (Die Rache Des Homunkulus) (1916)- Germany Verdens Undergang (1916) Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1916) Himmelskibet (1917) First Men in the Moon (1919) The Lost World (1925) Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924)- Russia Late 20’s/30’s Metropolis (1927, Ger.) Mysterious Island (1929) The Woman in the Moon (1929) Just Imagine (1930) Frankenstein (1931) Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) Doctor X (1932) The Invisible Man (1933) Island of Lost Souls (1933) King Kong (1933) The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) She (1935) Flash Gordon: serial (1936/reissue 1938 as “Rocketship”) Spaceship to the Unknown Flash Gordon(1936) The Invisible Ray (1936) The Devil Doll (1936) Bride of Frankenstein (1935) Things to Come (1936) The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1937) Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (1938) –serial (originally Space Soldiers) Deadly Ray from Mars (1938) –Flash Gordon Buck Rogers Conquers the Universe (1939)- serial 40’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940)-serial Dr. Cyclops (1940) The Invisible Man Returns (1940) The Invisible Woman (1940) The Monster and the Girl (1941) Invisible Agent (1942) The Purple Monster Strikes (1945)- serial (aka D-Day on Mars) Unknown Island (1948) Bruce Gentry - Daredevil of the Skies (1949) -serial A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1949) 50’s Destination Moon (1950) -

Television Reviews

Page 97 TELEVISION REVIEWS Sympathy for the Devil? Appropriate Adult (ITV 1, September 2011) Not much feted previously for the quality of its dramas (unless it was by fans of outlandish psycho thrillers about the perils of adultery), ITV has recently been enjoying a renaissance in quality that has made even the BBC sit up and take notice, as witnessed by lastyear’s much hyped Downtown Abbey / Upstairs Downstairs faceoff (the enjoyably preposterous Downtown Abbey walked away with all the prizes and plaudits). However, producing a drama based on events surrounding one of the most notorious crime stories of the 1990s – the serial killing exploits of gruesome twosome Fred and Rosemary West – was always going to be a rather more delicate proposition than assembling an assortment of noted Thesps in a stately home and letting them get on with talking ponderously about how “War changes things...” Let’s face it, the serial killer biopic is a particularly debased format, as epitomised most vividly in the distasteful antics of the now defunct (but much lamented, at least until its partial reincarnation as Palisades/Tartan) Tartan Metro company, which was a respectful and intelligent distributor of international and hardtoget genre films but which also helped bankroll three particularly regrettable movies of this type. These were; the sordid, workmanlike Ed Gein (2000), the deeply offensive (on many levels) Ted Bundy (2003) – which actually soundtracked a montage sequence depicting Bundy’s peripatetic assaults on dozens of young women with comedy music and the supposedly “hilarious” sound of his victims being hit on the head – and the equally repugnant The Hillside Strangler (2006). -

(Buddy) Ball Papers, 1959-1987 Coll2014-004

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z47s6 No online items Finding Aid to the Jim (Buddy) Ball Papers, 1959-1987 Coll2014-004 Jeff Snapp Processing this collection has been funded by a generous grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 (213) 821-2771 [email protected] URL: http://one.usc.edu Finding Aid to the Jim (Buddy) Coll2014-004 1 Ball Papers, 1959-1987 Coll2014-004 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Jim (Buddy) Ball papers creator: Ball, Jim (Buddy) (James L. Ball) Identifier/Call Number: Coll2014-004 Physical Description: 4 Linear Feet2 archive boxes + 1 flat archive box Date (inclusive): 1959-1987 Abstract: James L. Ball, Ph.D., known as "Buddy" Ball, produced films, records, and videos from about 1977 to 1997 for a variety of audiences including African American churches and other Christian groups, crafters, gay men, and horror fans. The collection includes corporate records, personal papers, and photographs documenting his varied activities from his early career as an educator to his involvement in motorcycle clubs to his inclusion in the banned-in-Britain "Video nasties" list. Arrangement This collection is arranged in the following series: Series 1. Corporate records, 1961-1998 Series 2. Personal records, 1959-1997 Biographical note During the years between 1960 and 2000, James L. Ball, Ph.D., (also known as Buddy Ball, Jim Ball, Jim L. Ball, Jim Lloyd Ball, Mr. -

Contents PROOF

PROOF Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgements x About the Contributors xi Introduction 1 1 A-Bombs, B-Pictures, and C-Cups 17 DavidJ.Skal 2 ‘It’s in the Trees! It’s Coming!’ NightoftheDemonand the Decline and Fall of the British Empire 33 Darryl Jones 3 Mutants and Monsters 55 Kim Newman 4 ‘Don’t Dare See It Alone!’ The Fifties Hammer Invasion 72 Wayne Kinsey 5 Genre, Special Effects and Authorship in the Critical Reception of Science Fiction Film and Television during the 1950s 90 Mark Jancovich and Derek Johnston 6 Hammer’s Dracula 108 Christopher Frayling 7 Fast Cars and Bullet Bras: The Image of the Female Juvenile Delinquent in 1950s America 135 Elizabeth McCarthy 8 ‘A Search for the Father-Image’: Masculine Anxiety in Robert Bloch’s 1950s Fiction 158 Kevin Corstorphine 9 ‘Reading her Difficult Riddle’: Shirley Jackson and Late 1950s’ Anthropology 176 Dara Downey vii July 5, 2011 12:20 MAC/CAME Page-vii 9780230_272217_01_prexiv PROOF viii Contents 10 ‘At My Cooking I Feel It Looking’: Food, Domestic Fantasies and Consumer Anxiety in Sylvia Plath’s Writing 198 Lorna Piatti-Farnell 11 ‘All that Zombies Allow’ Re-Imagining the Fifties in Far from Heaven and Fido 216 Bernice M. Murphy Bibliography 234 Filmography 244 Index 250 July 5, 2011 12:20 MAC/CAME Page-viii 9780230_272217_01_prexiv PROOF 1 A-Bombs, B-Pictures, and C-Cups1 David J. Skal When the atomic bomb leveled Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, newspaper readers learned not only of the appalling devastation but also of the explosion’s unearthly beauty, a glowing hothouse blossom rising to the heavens.