Goodbye, Stranger Matt Bondurant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock and Roll Customers

Rock and Roll Customers 10CC Deep Purple John Martyn Paul McCartney Steve Hillage Abba Demis Roussos John Miles PFM Strawbs AC/DC Depeche Mode John Paul Jones Pink Floyd Supertramp Ace Dire Straits Julio Inglesias Pretenders Sweet Adam Ant ELP Justin Hayward Procul Harem Sweet Sensation Alan Parker Elton John Kate Bush Queen Swingle Singers Alex Harvey Eric Clapton Kiki Dee Ralph McTell Tangerine Dream Bad Manners Fabulous Poodles Kinks Ritchie Blackmore Ten Years After Barbara Dickson Frankie Miller Kokomo Rod Argent The Headboys Barclay James Harvest Gallagher & Lyle Led Zeppelin Rod Stewart The Slits Bay City Rollers Genesis Leo Sayer Roger Glover The Who Bee Gees Gilbert O’Sullivan Lindisfarne Rolling Stones Thin Lizzy Boomtown Rats Graham Parker Lone Star Ronnie Lane Three Degrees Boxer Harry Belafonte Love Machine Rory Gallagher Tom Robinson Bryan Ferry Hawkwind Madness Roxy Music Tubeway Army Camel Heavy Metal Kids Marvin Gaye Roy Harper Ultravox Caravan Hi Tension Meal Ticket Rubettes Uriah Heep Charles Aznavour Home Mike Oldfield Showaddywaddy Vinegar Joe Charlie Charles Horslips Moody Blues Small Faces Wings Chris Stanton Ian Dury Mud Smokie Wizzard Climax Blues Band Ian Gillan Band Mungo Jerry Snafu YES Cockney Rebel Iron Maiden Nazareth Soft Machine Colosseum Jeff Wayne Osibisa Sparks David Coverdale Jess Roden Paper Lace Status Quo David Essex Jethro Tull Patrick Moraz Steeleye Span www.cpcases.com 34 . -

Song List - by Song - Mr K Entertainment

Main Song List - By Song - Mr K Entertainment Title Artist Disc Track 02:00:00 AM Iron Maiden 1700 5 3 AM Matchbox 20 236 8 4:00 AM Our Lady Peace 1085 11 5:15 Who, The 167 9 3 Spears, Britney 1400 2 7 Prince & The New Power Generation 1166 11 11 Pope, Cassadee 1657 4 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 803 12 22 Allen, Lily 1413 3 22 Swift, Taylor 1646 15 23 Mike Will Made It & Miley Cyrus 1667 16 33 Smashing Pumpkins 1662 11 45 Shinedown 1190 19 98.6 Keith 1096 4 99 Toto 1150 20 409 Beach Boys, The 989 7 911 Jean, Wyclef & Mary J. Blige 725 4 1215 Strokes 1685 12 1234 Feist 1125 12 1929 Deana Carter 1636 15 1959 Anderson, John 1416 7 1963 New Order 1313 1 1969 Stegall, Keith 1004 13 1973 Blunt, James 1294 16 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 820 4 1982 Estefan, Gloria 153 1 1982 Travis, Randy 367 5 1983 Neon Trees 1522 14 1984 Bowie, David 1455 14 1985 Bowling For Soup 670 5 1994 Aldean, Jason 1647 15 1999 Prince 182 9 Dec-43 Montgomery, John Michael 1715 4 1-2-3 Berry, Len 46 13 # Dream Lennon, John 1154 3 #1 Crush Garbage 215 12 #Selfie Chainsmokers 1666 6 Check Us Out Online at: www.AustinKaraoke.com Main Song List - By Song - Mr K Entertainment (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations 1199 5 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Reeves, Martha And The Vandellas 1199 6 (Your(The Angels Love Keeps Wanna Lifting Wear Me) My) Higher Red Shoes And Costello, Elvis 1209 4 Higher Wilson, Jackie 1199 8 (You're My) Soul & Inspiration Righteous Brothers 963 7 (You're) Adorable Martin, Dean 1375 11 1 2 3 4 Feist 939 14 1 Luv E40 & Leviti 1499 9 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 746 5 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

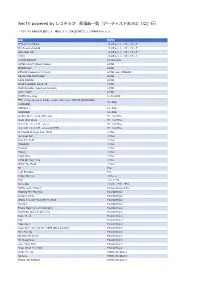

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Œa-DSM SERVICE DE PHYSIQUE THEORIQUE

FR0108562 CEA-SPHT-RA-l 998-2000 SERVICE DE PHYSIQUE THÉORIQUE RAPPORT D'ACTIVITE JUIN 1998 - MAI 2000 œa-DSM SERVICE DE PHYSIQUE THEORIQUE RAPPORT D'ACTIVITE JUIN 1998 - MAI 2000 PHYSIQUE THEORIQUE CEA/DSM Centre d'Etudes de Saclay F-91191 Gîf-sur-Yvette Cedex Tel: +33 (0)1 6908 7385 - Fax: +33 (0)1 6908 8120 URL: http://www-spht.cea.fr Cover : Time evolution of a two-dimensional Ising system at zero temperature. Coarsening can be observed in the bottom row snapshots (time 400 and 1000). Corresponding time-averaged magnetizations of each spin are represented on the top row in a color code varying continuously from blue to red; black dots identify persistent spins (which have never nipped). GENERAL CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (written in French) 1 QUANTUM FIELD THEORY AND MATHEMATICAL PHYSICS 5 NUCLEAR PHYSICS, PARTICLE PHYSICS AND ASTROPHYSICS ... 21 STATISTICAL PHYSICS AND CONDENSED MATTER 43 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS 69 LIST OF REFERENCES 93 APPENDICES (written in French) 95 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK INTRODUCTION Le rapport d'activité du Service de Physique Théorique est établi tous les deux ans. Celui- ci résume l'activité scientifique du SPhT durant la période juin 1998-mai 2000, et servira de document de base pour l'évaluation du laboratoire qui aura lieu à l'automne 2000. Pour la première fois la partie scientifique de ce rapport est écrite en anglais. Il y a plusieurs raisons à cela. D'une part un nombre important de collègues étrangers, pas tous francophones, participent à notre conseil scientifique extérieur (CSE). -

Exploring Cosmic Strings: Observable Effects and Cosmological Constraints

EXPLORING COSMIC STRINGS: OBSERVABLE EFFECTS AND COSMOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS A dissertation submitted by Eray Sabancilar In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2011 ADVISOR: Prof. Alexander Vilenkin To my parents Afife and Erdal, and to the memory of my grandmother Fadime ii Abstract Observation of cosmic (super)strings can serve as a useful hint to understand the fundamental theories of physics, such as grand unified theories (GUTs) and/or superstring theory. In this regard, I present new mechanisms to pro- duce particles from cosmic (super)strings, and discuss their cosmological and observational effects in this dissertation. The first chapter is devoted to a review of the standard cosmology, cosmic (super)strings and cosmic rays. The second chapter discusses the cosmological effects of moduli. Moduli are relatively light, weakly coupled scalar fields, predicted in supersymmetric particle theories including string theory. They can be emitted from cosmic (super)string loops in the early universe. Abundance of such moduli is con- strained by diffuse gamma ray background, dark matter, and primordial ele- ment abundances. These constraints put an upper bound on the string tension 28 as strong as Gµ . 10− for a wide range of modulus mass m. If the modulus coupling constant is stronger than gravitational strength, modulus radiation can be the dominant energy loss mechanism for the loops. Furthermore, mod- ulus lifetimes become shorter for stronger coupling. Hence, the constraints on string tension Gµ and modulus mass m are significantly relaxed for strongly coupled moduli predicted in superstring theory. Thermal production of these particles and their possible effects are also considered. -

POPULAR MUSIC from the 1970S

POPULAR MUSIC FROM THE 1970s Week of May 18 1. Watch the video “Elders React to Top Ten Songs of 1970s” Video - Elders React to 1970s 2. MUSIC OF THE 1970s: A few trends The 1970s saw many styles of popular music and countless numbers of recording artists. This week you will experience a mere taste of three types of music from this diverse decade. ● HARD ROCK - These artists turned up the volume. ● COUNTRY ROCK/SOUTHERN ROCK - Country music sensibilities + rock instruments ● DISCO - It was all about providing music so people could “boogie” (1970s slang for “dance.”) Your task: Choose one song in each of the three categories below (for a total of three songs.) Find and listen to all three. Come back to them a day or two later and listen to them again so you become especially familiar with them. (Note: If you don’t like one of the songs you first choose, choose a different one) HARD ROCK (choose one) Led Zeppelin - Stairway To Heaven Queen - Bohemian Rhapsody Aerosmith - Walk This Way COUNTRY ROCK / SOUTHERN ROCK (choose one) Linda Ronstadt - You’re No Good The Eagles - Hotel California Lynyrd Skynyrd - Sweet Home Alabama DISCO (choose one) The Bee Gees - Stayin’ Alive Donna Summer - Last Dance KC and the Sunshine Band - That’s the Way I Like It Earth, Wind and Fire - Boogie Wonderland You will not submit anything this week; just enjoy the music! Week of May 25 Music of the 1970s: Become an Expert (Take two weeks to complete this assignment) Select one musical act from the 1970s. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research And

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] H & H - Deep Hackberry Ramblers - Crowley Waltz Hackberry Ramblers - Tickle Her Hackett, Bobby - New Orleans Hackett, Buddy - Advice For young Lovers Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Laundry (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Rock and Egg Roll Hackett, Buddy - Diet Hackett, Buddy - It Came From Outer Space Hackett, Buddy - My Mixed Up Youth Hackett, Buddy - Old Army Routine Hackett, Buddy - Original Chinese Waiter Hackett, Buddy - Pennsylvania 6-5000 (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Songs My Mother Used to Sing To Who 1993 Haddaway - Life (Everybody Needs Somebody To Love) 1993 Haddaway - What Is Love Hadley, Red - Brother That's All (Meteor 5017) Hadley, Red - Ring Out Those Bells (Meteor 5017) 1979 Hagar, Sammy - (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Eagle's Fly 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Give To Live 1984 Hagar, Sammy - I Can't Drive 55 1982 Hagar, Sammy - I'll Fall In Love Again 1978 Hagar, Sammy - I've Done Everything For You 1978 1983 Hagar, Sammy - Never Give Up 1982 Hagar, Sammy - Piece Of My Heart 1979 Hagar, Sammy - Plain Jane 1984 Hagar, Sammy - Two Sides -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

GCSE, AS and a Level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet

GCSE, AS and A level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9 - 1) in Music (1MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) First teaching from September 2016 First certification from 2017 (AS) 2018 (GCSE and A level) Issue 1 Contents Introduction 1 Difficulty Levels 3 Piano 3 Violin 48 Cello 71 Flute 90 Oboe 125 Cla rinet 146 Saxophone 179 Trumpet 217 Voic e 240 Voic e (popula r) 301 Guitar (c lassic al) 313 Guitar (popula r) 330 Elec tronic keyboa rd 338 Drum kit 344 Bass Guitar 354 Percussion 358 Introduction This guide relates to the Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9-1) in Music (1MU0), Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) and Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) qualifications for first teaching from 2016. This guide must be read and used in conjunction with the relevant specifications. The music listed in this guide is designed to help students, teachers, moderators and examiners accurately judge the difficulty level of music submitted for the Performing components of the Pearson Edexcel GCSE, AS and A level Music qualifications. Examples of solo pieces are provided for the most commonly presented instruments across the full range of levels. Using these difficult y levels For GCSE, teachers will need to use the book to determine the difficulty level(s) of piece(s) performed and apply these when marking performances. For AS and A Level, this book can be used as a guide to assist in choosing pieces to perform, as performances are externally marked. -

Pharaoh Bible

1. CHARACTERS Pharaoh is essentially an “upstairs/downstairs” story, featuring a wide array of charac- ters of widely disparate social circumstances. The “upstairs” stories feature individuals in positions of power--priests, kings and nota- bles—many of which are based on actual historical figures who lived in the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Era (see italicized). Conversely, the “downstairs” story is driven by commoners, reflecting the prosaic lives of the average citizen—bureaucrats, soldiers, laborers and criminals—and based upon the latest research that is even now painting a new, utterly compelling picture of daily life in ancient Egypt. PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS: HATSHEPSUT Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thut- mose the First and Queen Ahmose. When she had come of age, her father arranged her marriage to her half-brother, Thut- mose the Second, and was the power be- hind the throne during his rule. Upon the death of her husband, Hatshep- sut believed her right to rule superseded Thutmose the Third’s due to her direct, “uncorrupted” lineage. Therefore, once she was appointed Thutmose the Third’s Regent, Hatshepsut assumed all of the regalia and symbols of royal office and insisted on being referred to in contempo- rary records as “His Majesty.” Hatshepsut, late-20s, is an extremely intelli- gent and capable woman who believes that she alone possesses the qualifications neces- sary to rule as King of Egypt. Upon her hus- band’s death, however, she is left powerless when his designated heir, Thutmose the Third, assumes the throne 2. HATSHEPSUT (CONT’D) and his trusted Vizier, Ahmose Pen-Nekhbet, is appointed the boy’s Regent. -

Alexandrea Ad Aegyptvm the Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity

Alexandrea ad aegyptvm the legacy of multiculturalism in antiquity editors rogério sousa maria do céu fialho mona haggag nuno simões rodrigues Título: Alexandrea ad Aegyptum – The Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity Coord.: Rogério Sousa, Maria do Céu Fialho, Mona Haggag e Nuno Simões Rodrigues Design gráfico: Helena Lobo Design | www.hldesign.pt Revisão: Paula Montes Leal Inês Nemésio Obra sujeita a revisão científica Comissão científica: Alberto Bernabé, Universidade Complutense de Madrid; André Chevitarese, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; Aurélio Pérez Jiménez, Universidade de Málaga; Carmen Leal Soares, Universidade de Coimbra; Fábio Souza Lessa, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; José Augusto Ramos, Universidade de Lisboa; José Luís Brandão, Universidade de Coimbra; Natália Bebiano Providência e Costa, Universidade de Coimbra; Richard McKirahan, Pomona College, Claremont Co-edição: CITCEM – Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar «Cultura, Espaço e Memória» Via Panorâmica, s/n | 4150-564 Porto | www.citcem.org | [email protected] CECH – Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Humanísticos | Largo da Porta Férrea, Universidade de Coimbra Alexandria University | Cornice Avenue, Shabty, Alexandria Edições Afrontamento , Lda. | Rua Costa Cabral, 859 | 4200-225 Porto www.edicoesafrontamento.pt | [email protected] N.º edição: 1152 ISBN: 978-972-36-1336-0 (Edições Afrontamento) ISBN: 978-989-8351-25-8 (CITCEM) ISBN: 978-989-721-53-2 (CECH) Depósito legal: 366115/13 Impressão e acabamento: Rainho & Neves Lda. | Santa Maria da Feira [email protected] Distribuição: Companhia das Artes – Livros e Distribuição, Lda. [email protected] Este trabalho é financiado por Fundos Nacionais através da FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto PEst-OE/HIS/UI4059/2011 manetho and the history of egypt luís manuel de Araújo University of Lisbon.