Collective Management in a Cooperative: Problematizing Productivity and Power Avery Edenfield University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Culture and Organizational Change- a Study on a Large Pharmaceutical Company in Bangladesh

Asian Business Review, Volume 4, Number 2/2014 (Issue 8) ISSN 2304-2613 (Print); ISSN 2305-8730 (Online) 0 Corporate Culture and Organizational Change- a Study on a Large Pharmaceutical Company in Bangladesh S.M. Rezaul Ahsan Senior Manager, Organization Development, The ACME Laboratories Ltd, Dhaka, BANGLADESH ABSTRACT This paper investigates the relationship between corporate culture and attitudes toward organizational change from the perspectives of a large pharmaceutical company in Bangladesh. A structured questionnaire was developed on the basis of the competing values framework of culture typology of Cameron and Quinn (2006) and a study of Justina Simon (June 2012), which was distributed to the 55 staff members of the company. The result shows that there is a significant relationship between corporate culture and organizational change. The study reveals that the organization has adopted all four types of organizational culture and the dominant existing organizational culture is the hierarchy culture. The study also shows that the resistance to change is a function of organizational culture. The implications of the study are also discussed. Key Words: Organizational Culture, Organizational Change, Resistance to change, Change Management JEL Classification Code: G39 INTRODUCTION Corporate culture is a popular and versatile concept in investigate the impact of organizational culture on C the field of organizational behavior and has been organizational change. identified as an influential factor affecting the success There has been significant research in the literature to and failure of organizational change efforts. Culture can explore the impact of organizational culture on both help and hinder the change process; be both a blessing organizational change. -

Organizational Structure

Organizational structure © 2019 The Predictive Index Organizational structure Why? When considering what will make a Organizational structure is the system that business strategy successful, it’s easy to defines how things get done on your team or in your organization, including task assignment, think of the people and resources needed managerial relationships, and communication. to move forward. However, the concept of Structures are developed during the process adjusting your organizational structure to known as organizational design, when you create a structure that allows you to best carry out your best suit your strategic vision is often strategic goals. Using the practice of neglected—despite the fact that structure organizational design, you can maximize your is a means by which you can successfully organizational structure by identifying blockers, creating new efficiencies, improving implement your strategy. communication, and eliminating or adding process steps where necessary. While the process of redesigning an organization’s structure is not a light undertaking, the consequences of the wrong organizational structure are considerable: lack of role clarity, diffusion of decision-making responsibility, siloed employees, and more. In this document, you’ll review a few crucial components of organizational structure, as well as several more popular structures and their benefits. 2 Structural components Spans and layers Managers’ average span of control and the Span of control number of layers in the chain of command Span of control refers to the number of subordinates reporting into any manager. Wide are often referred to by analysts as “spans span of control is appropriate when efficiency is and layers.” There are two considerations of crucial importance, or when many employees to make here: firstly, how wide should span in a division have similar goals and can therefore be managed by the same person. -

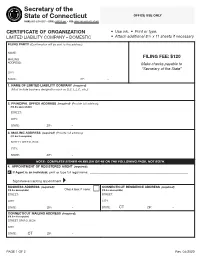

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Su Ppo R T D O Cu M En T

v T Structures and cultures: A review of the literature Support document 2 EN BERWYN CLAYTON M VICTORIA UNIVERSITY THEA FISHER CANBERRA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROGER HARRIS CU UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA ANDREA BATEMAN BATEMAN & GILES PTY LTD O MIKE BROWN UNIVERSITY OF BALLARAT D This document was produced by the author(s) based on their research for the report A study in difference: Structures and cultures in registered training organisations, and is an added resource for T further information. The report is available on NCVER’s website: <http://www.ncver.edu.au> R O The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government, state and territory governments or NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the P author(s). © Australian Government, 2008 P This work has been produced by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) on behalf of the Australian Government and state and territory governments U with funding provided through the Australian Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Apart from any use permitted under the CopyrightAct 1968, no S part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Requests should be made to NCVER. Contents Contents 2 Tables and figures 3 A review of the literature 4 Section 1: Organisational structure 4 Section 2: Organisational culture 21 Section 3: Structures and cultures – a relationship 38 References 41 Appendix 1: Transmission -

Historical Evolution of Management Accounting

1990's: Value Based Management Focus shifted to include the creation of customer value, strategy, balanced scorecards, EVA, and other related concepts. 1980's: Lcan Enterprise CA M-I Cost Management Focus shifted to the reduction of waste, JTT, teamwork, ABC, target costing, quality, investment & product life cycle management. 1951 - 1980's: Managerial Accounting Focus shifted to providinginformation for management planning & control. 1920 - 1950: Cost Accounting Matching concept developed. Focus on cost determination and financial control. 1812 - 1920: Accountingfor Processes Prior to the matching concept. Focus on operating cost and efficiency of processes. Shah Kamal Historical Evolution of Assistant Relationship Manager Management Accounting Bank Alfalah [email protected] Abstract The obsolescence of most companies' cost accounting and management control systems is particularly unfortunate for the global competition of the 1980s (Johnson & Kaplan, 1987). During the past two decades, conventional cost and management accounting practices have been under extensive criticism for their malfunction to instigate change and their inability to support management accounting innovations in coping with the requirements of a changing environment. The academic literature has been crucial of conventional management accounting systems particularly for their lack of efficiency and capability to present comprehensive and the latest information and to assure decision makers and potential users of such information. Focusing on this debate, current study reviews the evolution of cost and management accounting innovations over the past century around the world and to examine whether there has been a significant impact of management accounting in the organization. The analyses suggest that management accounting is changing. However, these changes do not have much bearing upon the type of management accounting techniques. -

Analysis of the Importance of Business Process Management Depending on the Organization Structure and Culture

Proceedings of the 2013 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems pp. 1079–1086 Analysis of the importance of business process management depending on the organization structure and culture Witold Chmielarz Marek Zborowski Aneta Biernikowicz University of Warsaw Faculty of University of Warsaw Faculty of BOC Information Technologies Management ul. Szturmowa 1/3, Management ul. Szturmowa 1/3, 02-678 Consulting al. Jerozolimskie 109/26, 02-678 Warszawa, Poland Warszawa, Poland 02-011 Warszawa, Poland Email: [email protected] Email: Email: aneta.biernikow- [email protected] [email protected] Abstract–the present survey mainly aims at analysing processes – more efficiently implemented than through determinants of possibilities of improving processes in an competition on a given market), where proper relations organization. The early fragments of the study are devoted to a result from combining the results of the processes with Key theoretical analysis of determinants of the process management Performance Indicators (KPI); the organizational structure – and its connection with the project management. Then the assumptions of the survey on the impact of the organizational with the possibility of questioning the inviolability and structure and culture on possibilities of applying business optimum of the present state, which serves a basis of a process management were presented. The verification of possibility of improving the organization, including also theoretical deliberations and survey assumptions is included in transferring and distributing tacit knowledge through a social the last part of the article presenting the initial results of the component of corporate portals and sharing it with other obtained survey and the resulting conclusions. -

Trade Management Guidelines

Trade Management Guidelines TRADE MANAGEMENT TASK FORCE Theodore R. Aronson, CFA, Chairman Aronson + Partners Gregory H. Bokach, CFA Damian Maroun American Century Investment Management G.E. Asset Management Corporation Eugene K. Bolton Jean Margo Reid G.E. Asset Management Corporation Paul Richards* Michael H. Buek, CFA Financial Services Authority The Vanguard Group H. Paul Reynolds Richard A. Carriuolo Frank Russell Securities, Inc. R.M. Davis, Inc. George U. Sauter Gene A. Gohlke, Ph.D., CPA* The Vanguard Group U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Erik R. Sirri Paul S. Gottlieb Babson College Merrill Lynch Wayne H. Wagner Joanne M. Hill Plexus Group Goldman, Sachs & Co. Jessica L. Mann, CFA Donald B. Keim CFA Institute The Wharton School Maria J. A. Clark, CFA Anthony J. Leitner CFA Institute Goldman, Sachs & Co. Ananth Madhavan ITG, Inc. * Observer. 1 CFA INSTITUTE TRADE MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES Recognizing the ambiguities and complexities surrounding the concept of Best Execution,1 CFA Institute Trade Management Task Force has developed the CFA Institute Trade Management Guidelines (Guidelines) for investment management firms (Firms). The recommendations contained herein stem from the obligations Firms have to clients regarding the execution of their trades and provide Firms with a demonstrable framework from which to make consistently good trade-execution decisions over time. The Guidelines formalize processes, disclosures, and record-keeping suggestions that, together, form a systematic, repeatable, and demonstrable approach to seeking Best Execution. It is important to note that the Guidelines are a compilation of recommended practices and not standards. CFA Institute encourages Firms worldwide to adopt as many of the recommendations as are appropriate to their particular circumstances. -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty Sulaiman, Said Musnadi Faculty of Economic and Business, University of Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia Keywords: Customer Relationship Management, Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty. Abstract: This study aims to determine the effect of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) on Customer Satisfaction and its impact on Customer Loyalty of Islamic Bank in Aceh’s Province. The study population is all customers in in the Islamic Bank. This study uses convinience random sampling with a sample size of 250 respondents. The analytical method used is structural equation modeling (SEM). The results showed that the Customer Relationship Management significantly influences both on satisfaction and its customer loyalty. Furthermore, satisfaction also affects its customer loyalty. Customer satisfaction plays a role as partially mediator between the influences of Customer Relationship Management on its Customer Loyalty. The implications of this research, the management of Islamic Bank needs to improve its Customer Relationship Management program that can increase its customer loyalty. 1 INTRODUCTION small number of studies on customer loyalty in the bank, as a result of understanding about the loyalty 1.1 Background and satisfaction of Islamic bank’s customers is still confusing, and there is a very limited clarification The phenomenon underlying this study is the low about Customer Relationship Management (CRM) as a good influence on customer satisfaction and its -

Vaccine Management Plan

Vaccine Management Plan KEEP YOUR MANAGEMENT PLAN NEAR THE VACCINE STORAGE UNITS Practices must maintain a vaccine management plan for routine and emergency situations to protect vaccines and minimize loss due to negligence. The Vaccine Coordinator and Backup are responsible for implementing the plan. Instructions: Complete this form and make sure key practice staff sign and acknowledge the signature log whenever your plan is revised. Ensure that all content (including emergency contact information and alternate vaccine storage location) is up to date. Keep the plan in a location easily accessible to staff and available for review by VFC Field Representatives during site visits. (For practices using mobile units to administer VFC vaccines: Complete the VFC “Mobile Unit Vaccine Management Plan” to itemize equipment and record practice protocols specific to mobile units.) Section 1: Important Contacts KEY PRACTICE STAFF & ROLES Office/Practice Name VFC PIN Number Address Role Name Title Phone # Alt Phone # E-mail Provider of Record Provider of Record Designee Vaccine Coordinator Backup Vaccine Coordinator Immunization Champion (optional) Receives vaccines Stores vaccines Handles shipping issues Monitors storage unit temperatures USEFUL EMERGENCY NUMBERS Service Name Phone # Alt Phone # E-mail VFC Field Representative VFC Call Center 1-877-243-8832 Utility Company Building Maintenance Building Alarm Company Refrigerator/Freezer Alarm Company Refrigerator/Freezer Repair Point of Contact for Vaccine Transport www.eziz.org 1 IMM-1122 (12/20) -

Five Key Principles of Corporate Performance Management

ffirs.qxd 11/2/06 1:49 PM Page iii Five Key Principles of Corporate Performance Management Bob Paladino John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 11/2/06 1:49 PM Page ii ffirs.qxd 11/2/06 1:49 PM Page i Additional Praise For Five Key Principles of Corporate Perfromance Management “This book is emblematic of Bob’s considerable expertise in organizing a company around the Strategy Focused Organization approach using the Balanced Scorecard Method. As founder, chairman and CEO of Crown Castle International (CCI:NYSE) I hired Bob as a consultant to lead a pro- gram to initiate CCI on the SFO method. He later joined CCI and led a suc- cessful organizational transformation to a much more efficient global platform in the telecommunications industry. I am now chairman and majority shareholder of two international organi- zations; one in the multi-jurisdictional payroll arena and another in the aero- space industry and Bob is successfully transforming those companies into Strategy Focused Organizations. He is probably THE most knowledgeable and experienced individual in implementing the SFO approach to better organizational efficiency given his hands on experience and his considerable knowledge of accounting and finance as a CPA.” —Ted B. Miller, Jr., Chairman, M7 Aerospace and Chairman, Imperium International “This book brings strategy to life through real-life application and provides the road map needed to truly unite a company in its objectives. Bob Paladino’s method encourages team work, cross functional thinking and drives company success.” —Preston Atkinson, Chief Operating Officer, Whataburger, Inc. “Bob Paladino has taken a balanced approach of taking all attributes of high performing businesses and turning them from theory to practical application. -

Professional Profile and the Role in the Cross-Functional Integration of SCM

Supply chain managers: professional profile and the role in the cross-functional integration of SCM Andréia de Abreu ( [email protected] ) Federal University of São Carlos Rosane Lúcia Chicarelli Alcântara ( [email protected] ) Federal University of São Carlos Abstract Supply chain management can be seen as a way to achieve integration of all corporate functions. Due to this, the objective of this paper is to present the theoretical indications regarding professional profile recommended for the supply chain management and discuss the role of these professionals in cross-functional business processes. Keywords: Supply chain management, Supply chain managers, Integration Introduction Despite the popularization of the concept since its introduction in the 1980s, the Supply Chain Management (SCM) is considered a discipline still in formation (Chen and Paulraj 2004, Tiwari et al. 2014). Its body of knowledge has been formed in confluence with areas such as logistics, operations management, information technology, marketing, resulting in principles and specific strategies, as demand management, postponement, e-supply chain, sustainable chain and others. In practice, SCM are complex and characterized by numerous activities spread over multiple functions and organizations, which pose challenges to reach effective implementation (Maleki and Cruz-Machado 2013). According to Teller et al. (2012) most of the initiatives to implement the practices and principles of SCM fail or are not completed. Studies have pointed out two main reasons for this fact: (i) the low observance of the human factor in behavioral and professional profile terms (Rossetti and Dooley 2010, Sohal 2013) and (ii) inadequate organizational structure to promote intra-organizational flows (Kim 2007, Oliva and Watson 2011), both have a negative impact on integration (Cousins and Menguc 2006, Fawcett et al.