East Soma AREA PLAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Breed's Troll Patrol

Start your summer here June events The Tablehopper says get ready for Merchant Roots p.14 June is festival time on Union Street, in North Beach, Lynette Majer has the perfect summer wine pairings p.15 at Stern Grove, at SF Jazz, Michael Snyder touts the can't-miss summer movies p.16 and in the local cinemas p.18 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 34TH YEAR VOLUME 34 ISSUE 06 JUNE 2018 Reynolds Rap London Breed’s troll patrol Is the mayoral candidate the company she keeps? BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS ’ve lived in the haight-ashbury district for three decades, and watched as it went from Left to right: Charles Sheeler, Classic Landscape, 1931. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO grief-stricken hippies pouring into the streets upon Ithe death of Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia to her- oin being sold off the hoods of cars to felonious tran- sients beating people up for their iPhones. I was so frus- The Cult of the Machine: Precisionism trated by District 5 Supervisor Ross Mirkarimi’s lack of action that, in 2010, I penned an editorial for Northside San Francisco magazine titled, “The thugs who run and American Art at the de Young Haight Street.” In 2012, much to my dismay, Mirkarimi was elected sheriff, and Mayor Ed Lee appointed Chris- BY SHARON ANDERSON tion. Originating from Cubism and combined highly structured, geomet- tina Olague to fill the supervisor position; however, Futurism, primarily European paint- ric compositions with smooth surfac- Olague’s tenure was short-lived as a bright, tenacious he de young museum is ing movements, Precisionism mar- es. -

San Francisco Passes Plastic-Bag Ban - Examiner.Com 04/14/2007 09:54 PM

San Francisco Passes Plastic-Bag Ban - Examiner.com 04/14/2007 09:54 PM e.g., article topic or author Search « Go back to yahoo.com Examiner.com Google Web National | Choose a Location RSS Feeds Choose your edition: No, thanks Atlanta Baltimore Boston Chicago Cleveland Dallas Denver Detroit Houston Indianapolis Los Angeles Miami Minneapolis New York Philadelphia Phoenix Pittsburgh Portland San Diego San Francisco San Jose Seattle St. Louis Washington DC Home News Politics Entertainment Sports Business Blogs Real Estate Jobs Autos Classifieds US World Asia Europe Latin America Middle East US This is the most recent version of this article. View article history. MORE US NEWS San Francisco Passes Plastic-Bag Ban Printer Friendly | PDF | Email Mar 28, 2007 9:53 AM (17 days ago) Font Size: a a A A By LISA LEFF, AP Current rank: Not ranked SAN FRANCISCO (Map, News) - City leaders approved a ban on plastic grocery bags after weeks of lobbying on both sides from environmentalists and a supermarket trade group. San Francisco would be the first U.S. city to adopt such a rule if Mayor Gavin Newsom signs the ban as expected. Storm Blamed for 5 Deaths Heads East The law, approved 10-1, requires large markets and drug stores to Suspect Arrested After Okla. Standoff (AP Photo/Ben Margot) offer customers bags made of paper that can be recycled, plastic Returning Troops Face Obstacles to Care Women shoppers walk with plastic bags that breaks down easily enough to be made into compost, or Tuesday, March 27, 2007, in the reusable cloth. -

Case 3:16-Cv-02859 Document 1 Filed 05/27/16 Page 1 of 26

Case 3:16-cv-02859 Document 1 Filed 05/27/16 Page 1 of 26 1 FRANK M. PITRE (SEN 100077) [email protected] 2 ALISON E. CORDOVA (SEN 284942) acordova@cpmlegaLcom 3 COTCHETT, PITRE & McCARTHY, LLP San Francisco Airport Office Center 4 840 Malcolm Road Eurlingame, CA 94010 5 Telephone: (650) 697-6000 Facsimile: (650) 697-0577 6 Attorneysfor Plaintiffs 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 JAMES STEINLE, individually and as CASE NO. heir to KATHRYN STEINLE, deceased; 11 ELIZABETH SULLIVAN, individually, COMPLAINT FOR DAMAGES: and as heir to KATHRYN STEINLE, 12 deceased; and JAMES STEINLE and 1. GENERAL NEGLIGENCE - ELIZABETH SULLIVAN, as co- WRONGFUL DEATH (Cal. Govt. 13 representatives ofthe Estate ofKATHRYN Code §§ 815.2(a) and 820(a)) STEINLE, 14 Plaintiffs, 2. PUBLIC ENTITY NEGLIGENCE 15 WRONGFUL DEATH (Cal. Evid. V. Code § 669) 16 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 3. NEGLIGENCE - SURVIVOR 17 a governmental entity; CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, a CAUSE OF ACTION 18 governmental entity; ROSS MIRKARIMI, an individual; and JUAN FRANCISCO 4. DEPRIVATION OF FEDERAL 19 LOPEZ-SANCHEZ, an individual. CIVIL RIGHTS (48 U.S.C. § 1983) 20 Defendants. JURY TRIAL DEMAND 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 LAW OFFICES COTCHETT.PrrRE& COMPLAINT McCarthy, LLP Case 3:16-cv-02859 Document 1 Filed 05/27/16 Page 2 of 26 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No» 2 I. INTRODUCTION 1 3 IT JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2 4 III. PARTIES 3 5 A. Plaintiffs and Decedent 3 6 B. Defendants 3 7 C. Agency and Concert ofAction 4 8 IV. -

Sanctuary City

11 Community 26 Real Estate 18 Calendar Supervisor: Dreamhouse: A August Events: It’s time Mark Farrell on saving the reborn Victorian 21 sanctuary city policy 7 for Outside Lands, the Stern Pet Pages Grove Festival, the Jewish Film Food & Wine Political Animal: Festival, the Marina Green 5K, and much more to keep you in New & Notable: Lord Saving dogs saved the summer spirit. 18 Stanley for the masses 11 Pali 26 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 31ST YEAR VOLUME 31 ISSUE 08 AUGUST 2015 Reynolds Rap Sanctuary city Killing draws national response, puts the sheriff in spotlight BY JOHN ZIPPERER rom City Hall to the U.S. Capitol in Wa s h - ington, lawmakers are responding to public dis- may over the apparently random killing of a Fwoman in San Francisco by an undocumented immi- grant. The death of 32-year-old Kathryn Steinle at the hands of Juan Francisco Lopez-Sanchez angered many, because Lopez-Sanchez has been deported five times before and has been convicted of seven felonies, yet before the killing he had been released by the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department under the sanctuary city policy that deters cooperation with federal immigration officials (via Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE). Critics say if ICE had been notified as they had requested about Lopez-Sanchez’s release, Lopez-Sanchez Kate Steinle on a trip to Zambia several years ago. PHOTO: COURTESY KATE STEINLE’S FACEBOOK PAGE would have been on his way back to Mexico and Steinle would be at home with her family. In 1989, San Francisco approved a sanctuary policy that I know why Kate loved elephants keeps city employees from cooperating with federal immi- gration authorities regarding investigations and arrests BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS Francisco Lopez-Sanchez, had five and Customs Enforcement (ICE). -

Fixing Our Troubled Justice System

Fixing Our Troubled Justice System Premier Distinguished Individual Table Sponsorship Table Sponsorship The Roe Foundation Tish and Steve Mead Steven and Jane Akin Mark and Lynne Rickabaugh C. Bruce and Holly Johnstone Polly Townsend Bill and Anngie Tyler Corporate Table Sponsorship Individual Table Sponsorship Robert L. Beal Al and Pat Houston Joseph Downing Dr. Gary and Susan Ellen and Bruce Kearney Herzfelder John and Jean Kingston Chuck and Teak Hewitt Preston and Susan Lucile and Bill Hicks McSwain Winner 9 Runners Up 18-44 Special Recognition 45-61 Los Angeles Police A Multi-Agency Approach Reducing Recidivism Academy Magnet Programs _______ 18 to Promote Reentry Through Education Alise Cayen Solutions, Reduce Recidivism Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi Reseda High School Police Academy and Control Costs ______________45 & Steve Good Daniel Bennett The Returning Home San Francisco Sheriff’s Department, Massachusetts Secretary of Public Safety and Security Ohio Pilot Project ______________22 Five Keys Charter School Terri Power The Ex-Offender Corporation for Supportive Housing Workforce Entrepreneur Project __ 50 Dave McMahon Intelligence-Driven Dismas House Prosecution _________________ 30 Cyrus Vance, Jr. The Employment Bridge Project ___54 District Attorney of New York County Michelle Jones Indiana Women’s Prison Paying for Success in Community Corrections _________39 Cross-lab Redundancy Kiminori Nakamura & Kristofer Bret Bucklen, in Forensic Science _____________58 Ph.D., on behalf of the Pennsylvania Department of Roger Koppl Corrections Syracuse University Competition Judges Pioneer Institute Board of Directors James L. Bush Officers Members Principal, Bush & Co. Stephen Fantone Steven Akin Diane Schmalensee Chairman Daniel F. Conley David Boit Kristin Servison Suffolk County District Attorney Lucile Hicks Nancy Coolidge Brian Shortsleeve Vice-Chair Andrew Davis Patrick Wilmerding Rev. -

Lemon Declaration with Exhibits.Pdf

DENNIS J. HERRERA, State Bar #139669 1 City Attorney JESSE C. SMITH, State Bar #122517 2 Chief Assistant City Attorney SHERRI SOKELAND KAISER, State Bar #197986 3 PETER J. KEITH, State Bar #206482 Deputy City Attorneys 4 1390 Market Street, Suite 700 San Francisco, California 94102-5408 5 Telephone: (415) 554-3886 (Kaiser) Telephone: (415) 554-3908 (Keith) 6 Facsimile: (415) 554-6747 E-Mail: [email protected] 7 [email protected] 8 Attorneys for MAYOR EDWIN M. LEE 9 ETHICS COMMISSION 10 CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO 11 12 13 In the Matter of Charges Against EXPERT DECLARATION OF NANCY K. D. LEMON 14 ROSS MIRKARIMI, 15 Sheriff, City and County of San Francisco. 16 17 I, NANCY K. D. LEMON, declare as follows: 18 1. I am an expert in domestic violence. I have focused on the issue of domestic 19 violence during my entire professional career. I was awarded a B.A. in Women’s Studies from the 20 University of California at Santa Cruz in 1975 and a J.D. from Boalt Hall School of Law, 21 University of California at Berkeley in 1980. Starting in 1981, I worked at several agencies 22 offering legal assistance to survivors of domestic violence. Through my work, I have come into 23 contact with thousands of such victims as well as with about a dozen perpetrators and reformed 24 perpetrators of abuse. 25 2. In 1988, I started teaching Domestic Violence Law at Boalt, and in 1990, I started 26 directing the Domestic Violence Practicum there. -

PIER 70 PREFERRED MASTER PLAN Table of Contents

P I E R 7 0 PREFERRED MASTER PLAN PORT OF SAN FRANCISCO APRIL 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mayor Gavin Newsom San Francisco Port Commission Rodney Fong, President San Francisco Board of Supervisors Stephanie Shakofsky, Vice President David Chiu, President, District 3 Kimberly Brandon Eric Mar, District 1 Michael Hardeman Michela Alioto-Pier, District 2 Ann Lazarus Carmen Chu, District 4 Monique Moyer, Executive Director Ross Mirkarimi, District 5 Chris Daly, District 6 Consultant Assistance Sean Elsbernd, District 7 Carey & Company Bevan Dufty, District 8 Economic Planning Systems, Inc. David Campos, District 9 Roma Design Group Sophie Maxwell, District 10 (Pier 70 is located in District 10) Treadwell & Rollo John Avalos, District 11 The Port is especially appreciative of Mayor Newsom, Supervisor The Port recognizes the time and dedication of the Port’s: Elsbernd and Supervisor Maxwell for their assistance and support in Central Waterfront Advisory Group (CWAG) the passage of Proposition D. PIER 70 PREFERRED MASTER PLAN TABle OF Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Site History 9 Chapter 2: Ship Repair, a Continuing Legacy 21 Chapter 3: Context for Change 27 Chapter 4: Past, Present, and Future 33 Chapter 5: Historic Preservation 37 Chapter 6: Land Use and Adaptive Reuse 45 Chapter 7: Open Space and Public Access 51 Chapter 8: Form and Character of Infill Development 57 Chapter 9: Transit, Circulation and Parking 71 Chapter 10: Implementation Strategy 75 Acknowledgements 101 Appendix A: Infill Development Density & Form Study 105 Appendix B: Financial -

Petitions and Communications Received from September 28, 2010

Petitions and Communications received from September 28, 2010, through October 8,2010, for reference by the President to Committee considering related matters, or to be ordered filed by the Clerk on October 19, 2010. From Southeast Community Facility Commission, submitting their Annual Statement of Purpose and Annual Report for FY2009-201 O. (1) From U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, submitting support for comprehensive immigration reform. Copy: Each Supervisor (2) From concerned citizens, submitting opposition to the sheer number of chain stores spreading all over the small shopping neighborhoods of San Francisco. 2 letters (3) From Abdalla Megahed, regarding his complaint against the building manager at 990 Polk Street. Copy: Each Supervisor (4) From Human Rights Commission, submitting request for waiver of Administrative Code Chapter 12B for Holiday Inn Golden Gateway. (5) From Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector, submitting their investment activity for fiscal year-to-date of the portfolios under the Treasurer's management. Copy: Each Supervisor (6) From Aaron Goodman, regarding the Parkmerced Project. 2 letters (7) From Department of Public Health, regarding the Ryan White HIV Emergency Relief Program. File No. 101253, Copy: Each Supervisor (8) From Office of the Controller, submitting the concession audit report of Paradies Shops. Paradies Shops has three lease agreements with the Airport Commission. (9) From Mordicai McGuire, regarding spending $450,000 to build a wheelchair ramp in the Board of Supervisors Legislative Chamber. Copy: Each Supervisor (10) From SF Environment, submitting the 2009 Annual Report for the Green Purchasing Program for City Staff. (11) I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I From Clerk of the Board, the Office of Economic and Workforce Development has submitted their 2010 Local Agency Biennial Notices: (12) From Fire Department, submitting an update on the utility infrastructure safety review. -

Mission Area Plan DEC 08 FINAL ADOPTED.Indd

Mission AREA PLAN An Area Plan of the General Plan of the City and County of San Francisco DECEMBER 2008 | ADOPTED VERSION Eastern Neighborhoods Community Plans AKNOWLEDGEMENTS MAYOR BOARD OF SUPERVISORS PLANNING COMMISSION Gavin Newsom Aaron Peskin, President Christina Olague, President Michela Alioto-Pier Michael J. Antonini Tom Ammiano Sue Lee Carmen Chu William L. Lee Chris Daly Kathrin Moore Bevan Dufty Hisashi Sugaya Sean Elsbernd Sophie Maxwell Jake McGoldrick Ross Mirkarimi Gerardo Sandoval SAN FRANCISCO PLANNING DEPARTMENT John Rahaim, Director of Planning With the Participation of the Following Public Agencies Dean Macris, Director of Planning (2004-2007) Association of Bay Area Governments Lawrence Badiner, Zoning Administrator City Administrator’s Offi ce Amit K. Ghosh, Chief of Comprehensive Planning Controller’s Offi ce Department of Building Inspection Department of Children, Youth & Families Eastern Neighborhoods Team Department of Public Health Gary Chen, Graphic Designer Department of Public Works Sarah Dennis, Housing/Public Benefi ts Program Manager Division of Emergency Services Sue Exline, Plan Manager Human Services Agency Claudia Flores, Planner Mayor’s Offi ce of Community Development Neil Hrushowy, Urban Designer Mayor’s Offi ce of Economic and Workforce Development Michael Jacinto, Environmental Planner Mayor’s Offi ce of Housing Johnny Jaramillo, Plan Manager Port of San Francisco Lily Langlois, Planner Recreation and Park Department Andres Power, Urban Designer San Francisco Arts Commission Ken Rich, Eastern Neighborhoods -

Bay Citizen/University of San Francisco Survey Findings Memo (Amended) October 2011 University of San Francisco, Leo T

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the McCarthy Center Faculty Publications Common Good 2011 Bay Citizen/University of San Francisco Survey Findings Memo (Amended) October 2011 University of San Francisco, Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_fac Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation University of San Francisco, Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, "Bay Citizen/University of San Francisco Survey Findings Memo (Amended) October 2011" (2011). McCarthy Center Faculty Publications. Paper 1. http://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_fac/1 This Survey is brought to you for free and open access by the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in McCarthy Center Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bay Citizen/University of San Francisco Survey Findings Memo (Amended) October 2011 Contents Survey Overview 1 Survey Methodology 2 Principal Findings 3 Mayor’s Race 5 District Attorney’s Race 12 Sheriff’s Race 14 Proposition C 15 Proposition D 19 Questionnaire and Top‐Line Results 22 Errata 29 About the University of San Francisco 30 http://www.usfca.edu/centers/mccarthy/ University of San Francisco, Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, October 2011 Survey Overview The Leo T. -

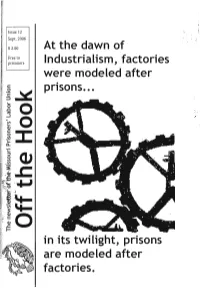

Off the Hook, but Especially to Those in Prison

Issue 12 Sept. 2006 $ 2.00 At the dawn of Free to prisoners Industrialism, factories were modeled after • ~ ~ pnsons ... ~ 0 ~o(\J .~ J: Q. in its twilight, prisons are modeled after factories. Missouri Prisoners' Labor Union A word from the editors :Cohteots ..... , ~;.. :,.-, . , To )<eep this project sustainable and improve the quality of each issue, we ask our readers to help us out in a few small Editorials 1 Mission Statement ways. Please inform us when your address • The MPLU recognizes the inherent dignity and inalienable rights of changes. This applies to everyone inter- . Letters 2 all members of the human family and the principle that the recognition ested in receiving issues of Off The Hook, but especially to those in prison. Roadblocks to organizing and adherence to said rights is the basis for freedom for all humans and Prison abolition will not be achieved faced by poor blacks 2 requisite to peace in the world. without the active involvement ofthose • The MPLU recognizes and believes that all prisoners are human behind the bars. In order for this newslet Youth who are rebelling ter to be a tool for our collective libera against society and why 4 beings as well as political prisoners and have a right to be freed from all tion, it is not only necessary that prisoners forms of abuse, oppression, repression, racism, sexism, and slave labor continue to read, think, and write but also Slave-breaking: part one 6 exploitation. discuss with fellow inmates, spread around copies of the newsletter, and send in lists of News 8 • The MPLU recognizes and believes in the people having the right to interested subscribers. -

Richland County Development & Services

RICHLAND COUNTY DEVELOPMENT & SERVICES COMMITTEE AGENDA Tuesday, MARCH 26, 2019 5:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS 1 of 237 The Honorable Gwen Kennedy, Chair County Council District 7 The Honorable Allison Terracio County Council District 5 The Honorable Jim Manning County Council District 8 The Honorable Chip Jackson County Council District 9 The Honorable Chakisse Newton County Council District 11 2 of 237 RICHLAND COUNTY COUNCIL 2019 Bill Malinowski Joyce Dickerson Yvonne McBride District 1 District 2 District 3 Blythewood 2018-2022 2016-2020 2016-2020 White Rock Dutch Fork Ballentine Irmo Dentsville Pontiac St. Andrews Arcadia Lakes Paul Livingston Allison Terracio Joe Walker, III Forest Acres District 4 District 5 District 6 Columbia 2018-2022 2018-2022 2018-2022 Horrell Hill Eastover Hopkins Gwendolyn Kennedy Jim Manning Calvin “Chip” Jackson Gadsden District 7 District 8 District 9 2016-2020 2016-2020 2016-2020 Dalhi Myers Chakisse Newton District 10 District 11 2016-2020 2018-2022 Richland County Development & Services Committee March 26, 2019 - 5:00 PM Council Chambers 2020 Hampton Street, Columbia, SC 29204 1. CALL TO ORDER The Honorable Gwen Kennedy 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES The Honorable Gwen Kennedy a. February 26, 2019 [PAGES 8-12] 3. ADOPTION OF AGENDA The Honorable Gwen Kennedy 4. ITEMS FOR ACTION a. I move that all RC contracts must be reviewed & approved by the Office of the County Attorney & that notices under or modifications to RC contracts must be sent to the County Attorney, but may be copied to external counsel, as desired [MYERS] [PAGES 13-14] b. Rural Zoning vs. Open Space Provision – Rural minimum lot size is 0.76 acre lots.