Cheneau V. Garland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Citizenship Law and the Means For

U.S. Department of Justice http://eoirweb/library/lib_index.htm Executive Office for Immigration Review Published since 2007 Immigration Law Advisor November 2008 A Monthly Legal Publication of the Executive Office for Immigration Review Vol 2. No.11 U.S. Citizenship Law and the Means for The Immigration Law Advisor is a professional monthly Becoming a Citizen newsletter produced by the by Katherine Leahy Executive Office for Immigration Review. The purpose of the n this election year, perhaps more than any other in recent memory, publication is to disseminate immigration issues have been at the forefront of the policy debate. judicial, administrative, IHowever, the very last matter on the minds of Americans who regulatory, and legislative rank immigration as an important political issue are the rather obscure developments in immigration law legal doctrines of derived and acquired citizenship. These concepts pertinent to the mission of the provided an interesting (albeit tangential) footnote to the presidential Immigration Courts and Board of race, as both Arizona Senator John McCain and one of his opponents Immigration Appeals. It is intended for the Republican nomination, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt only to be an educational resource for Romney, can point to the operation of the law of acquired citizenship in the use of employees of the Executive their recent family histories. Office for Immigration Review. Article II of the U.S. Constitution requires that the President of the United States be a “natural born citizen,” which led some to question whether McCain, who was born in the Panama Canal Zone while his In this issue.. -

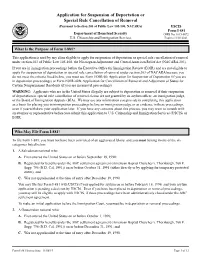

Form I-881, Application for Suspension of Deportation

Application for Suspension of Deportation or Special Rule Cancellation of Removal (Pursuant to Section 203 of Public Law 105-100, NACARA) USCIS Form I-881 Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0072 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Expires 11/30/2021 What Is the Purpose of Form I-881? This application is used by any alien eligible to apply for suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal under section 203 of Public Law 105-100, the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA 203). If you are in immigration proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) and are not eligible to apply for suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal under section 203 of NACARA because you do not meet the criteria listed below, you must use Form EOIR-40, Application for Suspension of Deportation (if you are in deportation proceedings) or Form EOIR-42B, Application for Cancellation of Removal and Adjustment of Status for Certain Nonpermanent Residents (if you are in removal proceedings). WARNING: Applicants who are in the United States illegally are subject to deportation or removal if their suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal claims are not granted by an asylum officer, an immigration judge, or the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). We may use any information you provide in completing this application as a basis for placing you in immigration proceedings before an immigration judge or as evidence in these proceedings, even if you withdraw your application later. If you have any concerns about this process, you may want to consult with an attorney or representative before you submit this application to U.S. -

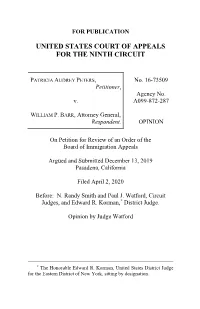

Peters V. Barr

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT PATRICIA AUDREY PETERS, No. 16-73509 Petitioner, Agency No. v. A099-872-287 WILLIAM P. BARR, Attorney General, Respondent. OPINION On Petition for Review of an Order of the Board of Immigration Appeals Argued and Submitted December 13, 2019 Pasadena, California Filed April 2, 2020 Before: N. Randy Smith and Paul J. Watford, Circuit Judges, and Edward R. Korman,* District Judge. Opinion by Judge Watford * The Honorable Edward R. Korman, United States District Judge for the Eastern District of New York, sitting by designation. 2 PETERS V. BARR SUMMARY** Immigration The panel granted Patricia Audrey Peters’s petition for review of a Board of Immigration Appeals’ decision, holding that Peters remains eligible for adjustment of status because she reasonably relied on her attorney’s assurances that he had filed the petition necessary to maintain her lawful status, and therefore, her failure to maintain lawful status was through no fault of her own. An individual is barred from adjusting status to become a lawful permanent resident if he or she “has failed (other than through no fault of his own or for technical reasons) to maintain continuously a lawful status since entry into the United States.” 8 U.S.C. § 1255(c)(2). However, skilled workers such as Peters remain eligible for adjustment of status as long as they have not been out of lawful status for more than 180 days. Peters argued that she fell out of lawful status through no fault of her own because either: 1) her attorney timely filed the necessary petition (as he said he did) and it was misplaced; or 2) the attorney did not file the petition. -

Adjustment of Status for VWP Entrants PM

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Office of the Director (MS 2000) Washington, DC 20529-2000 November 14, 2013 PM-602-0093 Policy Memorandum SUBJECT: Adjudication of Adjustment of Status Applications for Individuals Admitted to the United States Under the Visa Waiver Program Purpose This policy memorandum (PM) provides guidance on the adjudication of Form I-485, Application to Register or Adjust Status, filed by immediate relatives of U.S. citizens who were last admitted under the Visa Waiver Program (VWP). This PM updates the Adjudicator’s Field Manual (AFM) by adding a new section (j) to Chapter 10.3 and 23.5 (AFM Update AD11-30). Scope This PM applies to, and is binding on, all U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) employees, unless specifically exempt. Authority • Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) sections 217, 245 and 245(c)(4) • 8 CFR 245.1(b) Background The VWP allows qualifying foreign nationals of designated countries to enter the United States for up to 90 days to conduct business or for pleasure without first obtaining a visa.1 Before a foreign national is admitted under the VWP, in addition to meeting certain requirements, he or she must waive the right to contest any action for removal, other than on the basis of an application for 1 INA section 217(a)(1). Pursuant to INA section 217(a)(1), an individual seeking admission under the VWP applies for admission as a nonimmigrant, as that term is defined in INA section 101(a)(15)(B), and is provided with a waiver of the visa requirement. -

Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Cancellation of Removal Toolkit

PRACTITIONER’S TOOLKIT ON CANCELLATION OF REMOVAL FOR LAWFUL PERMANENT RESIDENTS 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Lawful Permanent Resident Cancellation of Removal Toolkit PART 1 ........................................................................................................................ 7 I. PREFACE ................................................................................................................ 8 2016 Edition .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 About the Center .............................................................................................................................................. 9 About the Pennsylvania Immigration Resource Center ................................................................................... 9 About the Redacted Version (Available Upon Request) ................................................................................... 9 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Statutory Section ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Case Law ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Practice Advisories ........................................................................................................................................ -

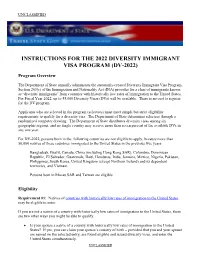

Instructions for the 2022 Diversity Immigrant Visa Program (Dv-2022)

UNCLASSIFIED INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE 2022 DIVERSITY IMMIGRANT VISA PROGRAM (DV-2022) Program Overview The Department of State annually administers the statutorily-created Diversity Immigrant Visa Program. Section 203(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides for a class of immigrants known as “diversity immigrants” from countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States. For Fiscal Year 2022, up to 55,000 Diversity Visas (DVs) will be available. There is no cost to register for the DV program. Applicants who are selected in the program (selectees) must meet simple but strict eligibility requirements to qualify for a diversity visa. The Department of State determines selectees through a randomized computer drawing. The Department of State distributes diversity visas among six geographic regions, and no single country may receive more than seven percent of the available DVs in any one year. For DV-2022, persons born in the following countries are not eligible to apply, because more than 50,000 natives of these countries immigrated to the United States in the previous five years: Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, China (including Hong Kong SAR), Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jamaica, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea, United Kingdom (except Northern Ireland) and its dependent territories, and Vietnam. Persons born in Macau SAR and Taiwan are eligible. Eligibility Requirement #1: Natives of countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States may be eligible to enter. If you are not a native of a country with historically low rates of immigration to the United States, there are two other ways you might be able to qualify. -

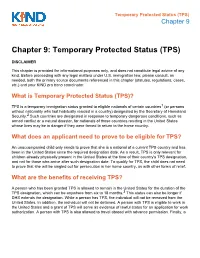

Chapter 9: Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) Chapter 9 Chapter 9: Temporary Protected Status (TPS) DISCLAIMER This chapter is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute legal advice of any kind. Before proceeding with any legal matters under U.S. immigration law, please consult, as needed, both the primary source documents referenced in this chapter (statutes, regulations, cases, etc.) and your KIND pro bono coordinator. What is Temporary Protected Status (TPS)? TPS is a temporary immigration status granted to eligible nationals of certain countries1 (or persons without nationality who last habitually resided in a country) designated by the Secretary of Homeland Security.2 Such countries are designated in response to temporary dangerous conditions, such as armed conflict or a natural disaster, for nationals of these countries residing in the United States whose lives may be in danger if they were forced to return to the home country. What does an applicant need to prove to be eligible for TPS? An unaccompanied child only needs to prove that she is a national of a current TPS country and has been in the United States since the required designation date. As a result, TPS is only relevant for children already physically present in the United States at the time of their country's TPS designation, and not for those who arrive after such designation date. To qualify for TPS, the child does not need to prove that she will be singled out for persecution in her home country, as with other forms of relief. What are the benefits of receiving TPS? A person who has been granted TPS is allowed to remain in the United States for the duration of the TPS designation, which can be anywhere from six to 18 months.3 This status can also be longer if DHS extends the designation. -

ILRC Opposes November 2020 USCIS Changes to the Policy

December 15, 2020 Delivered via email to: USCIS [email protected]. cc: Joseph Edlow, USCIS Deputy Director for Policy [email protected] cc: DHS Office of Inspector General [email protected] cc: Michael Dougherty DHS Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman [email protected] cc: [email protected] cc: [email protected] cc: [email protected] RE: USCIS PM – Use of Discretion for Adjustment of Status, Changes to 7 USCIS-PM A.1 and 7 USCIS-PM A.10, effective upon publication on November 17, 2020. Dear USCIS: I am writing on behalf of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) to oppose the policy manual changes, Applying Discretion in USCIS Adjudications, cited above,1 which superseded the Adjudicator’s Field Manual (AFM) 10.15.2 In July 2020, USCIS also altered the policy manual on discretion in dozens of USCIS benefits applications, at 1 USCIS-PM E.8 and 10 USCIS-PM A.5.3 We oppose the present changes to the policy manual, as we did the July changes,4 because they violate existing case law. The changes represent an attempt to impose new eligibility requirements that are also a violation of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) because they went into effect without the required regulatory notice and comment process. The agency has provided no explanation for this abrupt departure from prior procedure and application of the law. In addition, the policy manual will unduly burden eligible applicants and USCIS adjudicators by requiring a separate, lengthy adjudication 1 See USCIS https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/policy-manual-updates/20201117- AOSDiscretion.pdf The new material in the policy manual is found here: https://www.uscis.gov/policy- manual/volume-7-part-a-chapter-10 and https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-7-part-a-chapter-1. -

Matter of C-J-H-, 26 I&N Dec. 284 (BIA 2014)

Cite as 26 I&N Dec. 284 (BIA 2014) Interim Decision #3798 Matter of C-J-H-, Respondent Decided March 27, 2014 U.S. Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review Board of Immigration Appeals An alien whose status has been adjusted from asylee to lawful permanent resident cannot subsequently readjust status under section 209(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1159(b) (2012). FOR RESPONDENT: Donald F. Madeo, Esquire, New York, New York FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY: Diane Dodd, Assistant Chief Counsel BEFORE: Board Panel: MALPHRUS, MULLANE, and CREPPY, Board Members. MALPHRUS, Board Member: In a decision dated May 8, 2013, an Immigration Judge found the respondent removable on his own admissions under sections 237(a)(2)(A)(i) and (iii) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1227(a)(2)(A)(i) and (iii) (2012), as an alien convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude and an aggravated felony. The Immigration Judge also denied the respondent’s application for readjustment of status in conjunction with a waiver of inadmissibility under sections 209(b) and (c) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1159(b) and (c) (2012), and ordered him removed from the United States. The respondent has appealed from that decision. The appeal will be dismissed. The respondent is a native and citizen of the People’s Republic of China who was admitted to the United States on January 10, 2006, as an asylee. He adjusted his status to that of a lawful permanent resident under section 209(b) of the Act on November 20, 2007. -

Adjustment Options for Temporary Protected Status Beneficiaries

Adjustment Options for Temporary Protected Status Beneficiaries Oct. 18, 2020 Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is a temporary immigration status for nationals of a country that is experiencing ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or another extraordinary and temporary condition. While TPS does not provide an independent path to Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) status, there are ways in which TPS may help some beneficiaries of immediate relative petitions become eligible for adjustment of status, even if the TPS beneficiary initially entered the United States without being “inspected and admitted or paroled.” However, three recent changes to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) policy make it increasingly difficult for many TPS beneficiaries to adjust status through family-based petitions. This practice advisory reviews these policy changes as well as options for adjustment that may still be available to help certain TPS beneficiaries adjust under Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) § 245(a), even if they initially entered the United States without being inspected and admitted or paroled.1 Eligibility requirements for adjustment of status under 245(a) To adjust under 245(a), an applicant must have been “inspected and admitted or paroled” upon their last entry; have an immigrant visa immediately available; and be admissible (or eligible for an inadmissibility waiver). In addition, INA § 245(c) imposes bars to adjustment that apply to any preference category beneficiary who has either worked without authorization or has failed to continuously maintain lawful immigration status since entry. Because most preference beneficiaries who are in the United States are subject to either or both bars, 245(a) adjustment is typically only available to immediate relatives who have been inspected and admitted or paroled, since immediate relatives are exempt from these bars. -

Are Temporary Protected Status Recipients Eligible to Adjust Status?

Legal Sidebari Are Temporary Protected Status Recipients Eligible to Adjust Status? Updated February 25, 2021 Certain non-U.S. nationals (aliens) who lack a permanent foothold in the United States may pursue adjustment of status and become lawful permanent residents (LPRs). To qualify, an alien must satisfy certain requirements, generally including having been “inspected and admitted or paroled” into the United States by immigration authorities. In recent years, some federal courts have addressed whether aliens who unlawfully entered the United States but later received Temporary Protected Status (TPS) are considered to be “inspected and admitted” into the United States. Reviewing courts have split on this issue. That said, even if an alien’s acquisition of TPS is treated as being “inspected and admitted” into the country, that alone does not provide a pathway to adjustment of status. An alien who was unlawfully present in the United States before receiving TPS would have to meet other requirements, such as being the beneficiary of an immigrant visa petition filed by a U.S. citizen spouse. This Legal Sidebar provides a brief overview of the adjustment of status framework and TPS, before examining the conflicting jurisprudence on TPS recipients’ eligibility for adjustment, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) guidance regarding the adjudication of adjustment applications filed by TPS recipients, and recent legislative proposals. Legal Background: Adjustment of Status and Temporary Protected Status Adjustment of Status Section 245(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security to adjust the status of the beneficiary of an approved immigrant visa petition (e.g., an immediate relative petition filed by a U.S. -

Instructions for I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence Or

OMB No. 1615-0023; Expires 06/30/2015 Instructions for I-485, Application to Register Department of Homeland Security U. S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Permanent Residence or Adjust Status What Is the Purpose of Form I-485? B. If you were admitted as the K-2 child of such a fiancé(e), you may apply to adjust status based on This form is used by a person who is in the United States to your parent's Form I-485. apply to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to adjust to permanent resident status or register for permanent 4. Based on asylum status residence. You may apply to adjust status after you have been This form may also be used by certain Cuban nationals to granted asylum in the United States if you have been request a change in the date that their permanent residence physically present in the United States for 1 year after the began. grant of asylum, provided you still qualify as an asylee or as the spouse or child of a refugee. Who May File Form I-485? 5. Based on refugee status 1. Based on an immigrant petition You may apply to adjust status after you have been admitted as a refugee and have been physically present in You may apply to adjust your status if: the United States for 1 year following your admission, A. An immigrant visa number is immediately available provided that your status has not been terminated. to you based on an approved immigrant petition; or 6. Based on Cuban citizenship or nationality B.