COPY ORIGINAL FEDERAL Communicationsfe8~Ssion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

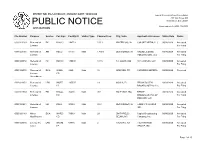

REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122670 Renewal of FM KLWL 176981 Main 88.1 CHILLICOTHE, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000123755 Renewal of FM KCOU 28513 Main 88.1 COLUMBIA, MO The Curators of the 01/21/2021 Granted License University of Missouri From: To: 0000123699 Renewal of FL KSOZ-LP 192818 96.5 SALEM, MO Salem Christian 01/21/2021 Granted License Catholic Radio From: To: 0000123441 Renewal of FM KLOU 9626 Main 103.3 ST. LOUIS, MO CITICASTERS 01/21/2021 Granted License LICENSES, INC. From: To: 0000121465 Renewal of FX K244FQ 201060 96.7 ELKADER, IA DESIGN HOMES, INC. 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122687 Renewal of FM KNLP 83446 Main 89.7 POTOSI, MO NEW LIFE 01/21/2021 Granted License EVANGELISTIC CENTER, INC From: To: Page 1 of 146 REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122266 Renewal of FX K217GC 92311 Main 91.3 NEVADA, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122046 Renewal of FM KRXL 34973 Main 94.5 KIRKSVILLE, MO KIRX, INC. -

2019 Nemo Fair Board of Directors

Phone (660) 465-7225 Toll Free (800) 748-7875 News and Weather General Store Coffee Break Local Sports Areas Best Music 2019 NEMO FAIR BOARD OF DIRECTORS Vice President Secretary Treasurer President Jason Kim Brittany Alan Wood Smith Huffman Saoirse-Whittom Jeremy Marilyn Frank Jim Whitlock Blickhan Vorhees Keim Rayburn Jeff Don Jody Mark Snell McVay Reynolds Farris Simler 2019 QUEEN COMMITTEE MEMBERS Member of The Kirksville Chamber of Commerce Jaimee Wood Edna Whitlock Paula Swisher Kristin Kinney Cathy Houston Laura Kaltenbach Shala Reynolds Gina Hubbard Shelley Story Cortney Diggins Shelby Hubbard CHECK OUT OUR WEB SITE!!!! NEMOFAIR.NET Follow us on Facebook. 1 Welcome to the 2019 NEMO Fair This is our 72nd Annual NEMO Fair. On behalf of all the NEMO Board of Directors, I would like to welcome everyone to the fair this year. We would like to thank the City of Kirksville, local businesses, and all of the volunteers. Without your continued support, it would not be possible to have the great success we have each year. We have a great line-up this year with three nights of music entertainment. Again this year, you can enjoy a full rodeo, truck & tractor pull, and demolition derby. New to the 2019 NEMO Fair is the Conner Family Amusements. We encourage you to support our area 4-H and FFA youth by attending the daily livestock shows and browsing their exhibits showcased in the 4-H and FFA building. Please make your way to the Multipurpose building to visit with vendors and cool off. The Fair Board thanks each and every person who attends and supports the Fair and our outstanding youth. -

Missouri Eas Plan

MISSOURI EAS PLAN STATE OF MISSOURI EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM OPERATIONAL PLAN This plan was prepared by the Missouri State Emergency Communications Committee in cooperation with the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency; the National Weather Service offices in St Louis, Pleasant Hill, Springfield, Paducah and Memphis; the Missouri Broadcasters Association; State and local officials; and the broadcasters and cable systems of Missouri. NOTE: EAS Operational Area operating procedures of the broadcasters, cable systems, State officials or the National Weather Service, relating to the State EAS Operational Plan will be attached as Annex K thru X to this plan. EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM (EAS) CHECKLIST FOR BROADCAST STATIONS AND CABLE SYSTEMS ______ 1. All personnel trained in EAS procedures and in the use of EAS equipment. ______ 2. EAS encoders and decoders installed and operating. ______ 3. Correct assignments monitored, according to EAS State or Local Area plans. ______ 4. Weekly and monthly EAS tests received and logged. ______ 5. Weekly and monthly EAS test transmissions made and logged. ______ 6. EAS Operating Handbook immediately available. ______ 7. Red Authenticator envelope immediately available (broadcasters only). ______ 8. Copies of EAS State and Local Area plans immediately available. ______ 9. Copy of FCC EAS Rules and Regulations (Part 11) and, if appropriate, AM station emergency operation (Section 73.1250) available. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page APPROVALS AND CONCURRENCES ........................... 1-2 PURPOSE ............................................. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

ONE MORE MONTH! and GULF TROPO HITS BIG TIME! Visit Us At

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association MAY 2009 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers PHOTO BY TIM ALDERMAN ONE MORE MONTH! AND GULF TROPO HITS BIG TIME! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info MAY 2009 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 4 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 11 secure way to join or renew your membership Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 20 in the WTFDA from our page at: Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 22 http://www.wtfda.org/join.html Western TV DX…Nick Langan 36 You can now renew either paper VUD 6 meters…Peter Baskind 38 membership or your online eVUD membership Analog Days 39 at one convenient stop. Use the link above to OBG From DX Horizons 41 either join the WTFDA or renew your Young Bruce Elving 42 membership in North America’s only TV and May 2009 Meteor Scatter Chart 43 DX organization. -

Moberly Area Community College

Moberly Area Community College ADJUNCT FACULTY HANDBOOK Revised August 2013 Adjunct Faculty Handbook Adjunct Faculty Handbook Table of Contents Introduction Preface ............................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the College ...................................................................................................... 1 Mission ............................................................................................................................... 1 Institutional Purposes ............................................................................................ 1 Vision Statement ................................................................................................................. 2 Institutional Values ................................................................................................ 2 General Information Absences ............................................................................................................................. 4 Adjunct Office .................................................................................................................. 4 Cafeteria .............................................................................................................................. 4 Central Processing Center ................................................................................................... 4 Employment Policies and Procedures ............................................................................... -

And ) WZZQ(FM), Terre Haute, Indiana )

Federal Communications Commission FCC 97D-09 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of MM Docket No. 95-154 CONTEMPORARY MEDIA, INC. ) Licensee of Stations WBOW(AM), WBFX(AM), and ) WZZQ(FM), Terre Haute, Indiana ) Order to Show Cause Why the Licenses for ) Stations WBOW(AM), WBFX(AM), and WZZQ(FM), ) Terre Haute, Indiana, Should Not be Revoked ) CONTEMPORARY BROADCASTING, INC. ) Licensee of Station KFMZ(FM), Columbia, ) Missouri, and Permittee of Station KAAM-FM, ) Huntsville, Missouri (unbuilt) ) Order to Show Cause Why the Authorizations for ) Stations KFMZ(FM), Columbia, Missouri, and ) KAAM-FM, Huntsville, Missouri, Should Not be ) Revoked ) LAKE BROADCASTING, INC. ) Licensee of Station KBMX(FM), Eldon, Missouri, ) and Permittee of Station KFXE(FM), Cuba, ) Missouri ) Order to Show Cause Why the Authorizations for ) Stations KBMX(FM), Eldon, Missouri, and ) KFXE(FM), Cuba, Missouri, Should Not be Revoked ) LAKE BROADCASTING, INC. ) File No. BPH-921112MH For a Construction Permit for a New FM Station ) on Channel 244A at Bourbon, Missouri ) Appearances Shelley Sadowsky, Esquire, Michael D. Gaffney, Esquire, Jerold L. Jacobs, Esquire, and Howard J. Braun, Esquire, on behalf of Contemporary Media, Inc., Contemporary Broadcasting, 14254 Federal Communications Commission FCC 97D-09 Inc., and Lake Broadcasting, Inc.; Robert A. Zauner, Esquire, and Anthony Mastando, Esquire, on behalf of the Chief, Mass Media Bureau, Federal Communications Commission. INITIAL DECISION OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE ARTHUR I. STEINBERG Issued: August 18, 1997 Released: August 21, 1997 PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. By Order to Show Cause and Notice of Apparent Liability, 10 FCC Red 13685 (1995) ("OSC"), the Commission directed Contemporary Media, Inc., Contemporary Broadcasting, Inc., and Lake Broadcasting, Inc. -

Postcard Data Web Clean Status As of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amoun

postcard_data_web_clean Status as of Facility ID. Call Sign Service Oct. 1, 2005 Class Population State/Community Fee Code Amount 33080 DDKVIK FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 IA DECORAH 0641 575 13550 DKABN AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million CA CONCORD 0627 3100 60843 DKHOS AM Station Licensed B up to 25,000 TX SONORA 0623 500 35480 DKKSL AM Station Licensed B 500,001 - 1.2 million OR LAKE OSWEGO 0627 3100 2891 DKLPL-FM FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 LA LAKE PROVIDENCE 0641 575 128875 DKPOE AM Station Const. Permit TX MIDLAND 0615 395 35580 DKQRL AM Station Licensed B 150,001 - 500,000 TX WACO 0626 2025 30308 DKTRY-FM FM Station Licensed A 25,001 - 75,000 LA BASTROP 0642 1150 129602 DKUUX AM Station Const. Permit WA PULLMAN 0615 395 50028 DKZRA AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 TX DENISON-SHERMAN 0625 1200 70700 DWAGY AM Station Licensed B 1,200,001 - 3 million NC FOREST CITY 0628 4750 63423 DWDEE AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MI REED CITY 0635 475 62109 DWFHK AM Station Licensed D 25,001 - 75,000 AL PELL CITY 0636 725 20452 DWKLZ AM Station Licensed B 75,001 - 150,000 MI KALAMAZOO 0625 1200 37060 DWLVO FM Station Licensed A up to 25,000 FL LIVE OAK 0641 575 135829 DWMII AM Station Const. Permit MI MANISTIQUE 0615 395 1219 DWQMA AM Station Licensed D up to 25,000 MS MARKS 0635 475 129615 DWQSY AM Station Const. -

Writer's Address Book Volume 4 Radio & TV Stations

Gordon Kirkland’s Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 Radio & TV Stations The Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 – Radio & TV Stations By Gordon Kirkland ©2006 Also By Gordon Kirkland Books Justice Is Blind – And Her Dog Just Peed In My Cornflakes Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse When My Mind Wanders It Brings Back Souvenirs The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Newspapers The Writer’s Address Book Volume 2 – Bookstores The Writer’s Address Book Volume 3 – Radio Talk Shows CD’s I’m Big For My Age Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse… Live! The Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 – Radio & TV Stations Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 9 US Radio Stations ............................................................................................................ 11 Alabama .........................................................................................................................11 Alaska............................................................................................................................. 18 Arizona ........................................................................................................................... 21 Arkansas......................................................................................................................... 24 California ........................................................................................................................ 31 Colorado ........................................................................................................................ -

Newspaper Organizations

CHAPTER 9 MISSOURI INFORMATION Cotton Harvest Photo courtesy of Missouri State Archives Publications Collection 864 OFFICIAL MANUAL Newspaper Organizations 802 Locust St., Columbia 65201 Telephone: (573) 449-4167 / FAX: (573) 874-5894 www.mopress.com The Missouri Press Association is an organiza- MARK MAASSEN tion of newspapers in the state. Executive Director Missouri Press Association Organized May 17, 1867, as the Editors and Publishers Association of Missouri, the name line County Herald newspaper office in historic was changed in 1877 to the Missouri Press As- Arrow Rock and maintains a newspaper equip- sociation (MPA). In 1922, the association became ment museum, which underwent renovations in a nonprofit corporation, and a central office was 2016, in connection with it. opened under a field manager whose job it was to travel the state and help newspapers with The Missouri Press Foundation administers problems. and funds seminars and workshops for newspa- per people, supports Newspapers In Education The association, located in Columbia, became programs, and funds scholarships and internships the fifth press association in the nation to finance for Missouri students studying community jour- its headquarters through member contributions. nalism in college. The MPA’s building was purchased in 1969. Membership in the association is voluntary. All As a founder of institutions, the Missouri daily newspapers in the state are members and 99 Press Association aided in the establishment of percent of the weekly newspapers are members. In the Confederate Soldiers’ Home, the upbuild- 2017, there were 236 weekly and daily newspa- ing of the normal schools, support of the public per members. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-201002-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 10/02/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000123163 Renewal of FX K286CI 144718 105.1 WATERLOO, IA COLOFF MEDIA, LLC 09/30/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000123160 Renewal of AM KBGG 87105 Main 1700.0 DES MOINES, IA RADIO LICENSE 09/30/2020 Accepted License HOLDING CBC, LLC For Filing 0000122950 Renewal of FX K283CI 140630 104.5 ST. LOUIS, MO 104 LICENSE, LLC 09/29/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000122072 Renewal of DCA WIMN- 2245 Main 36 ARECIBO, PR CARMEN CABRERA 09/30/2020 Received License CD Amendment 0000122951 Renewal of LPD WQFT- 185537 18 OCALA, FL FRANK DIGITAL 09/29/2020 Accepted License LD BROADCASTING LLC For Filing 0000122984 Renewal of FM KYOO- 36015 Main 99.1 HALF WAY, MO BENNE 09/29/2020 Accepted License FM BROADCASTING OF For Filing BOLIVAR, LLC 0000123281 Renewal of FM KDFR 20849 Main 91.3 DES MOINES, IA FAMILY STATIONS, 09/30/2020 Accepted License INC. For Filing 0000123118 Minor DCA WARZ- 71089 Main 23 SMITHFIELD- Capitol Broadcasting 09/30/2020 Accepted Modification CD SELMA, NC Company, Inc. For Filing 0000123035 License To LPD WUVM- 69785 Main 2 ATLANTA, GA HC2 STATION 09/30/2020 Accepted Cover LP GROUP, INC For Filing Page 1 of 20 REPORT NO. PN-1-201002-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 10/02/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. -

Columbia Missourian Stylebook Mid-Missouri

COLUMBIA MISSOURIAN STYLEBOOK and a guide to MID-MISSOURI JULY 2015 5-MINUTE STYLEBOOK (How 10 percent of the rules cover 90 percent of style questions) MEMORIZE THESE NUMBERS n In general, zero through nine are written out, and 10 and RULES. above are written as numerals. Below are style guidelines that you should know without n Always use numerals, even if less than 10, with: having to refer to a stylebook. They’re taken from the Mis- sourian and AP stylebooks and from dictionary listings. If you n addresses (3 Hospital Drive) learn them, your life will be easier and your editors happier. n ages (7 years old) n dates (March 4) n distances (4 miles) n heights (5 feet 11 inches) PEOPLE n million, billion and trillion (9 million people) n money ($5) n Capitalize formal titles when they appear before names, n percentages (8 percent) and lowercase titles when they follow a name or stand alone n time (2 p.m.) (former President Vicente Fox; President Barack Obama; n weights (6 pounds) George Bush, former president). n n Lowercase occupational or descriptive titles before or after Spell out any number, except a year, that begins a sen- a name. Mere job descriptions (such as astronaut, announc- tence. (Twelve students attended. 1999 was an important er or teacher) are not capitalized before or after a name year.) (reporter Casey Law; Casey Law, a reporter). If you are not n For most numbers of a million or more, use this form, sure whether a title is a formal, official title or merely a job rounded off to no more than two decimal places: 1.45 mil- description, put the title after the name and lowercase it.