The Mysterious Disappearance of Father Buliard, O.M.I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mercury in Freshwater Ecosystems of the Canadian Arctic: Recent Advances on Its Cycling and Fate

STOTEN-16426; No of Pages 26 Science of the Total Environment xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Review Mercury in freshwater ecosystems of the Canadian Arctic: Recent advances on its cycling and fate John Chételat a,⁎,MarcAmyotb,PaulArpc, Jules M. Blais d, David Depew e, Craig A. Emmerton f, Marlene Evans g, Mary Gamberg h,NikolausGantneri,1, Catherine Girard b, Jennifer Graydon f,JaneKirke,DavidLeanj, Igor Lehnherr k, Derek Muir e,MinaNasrc, Alexandre J. Poulain d, Michael Power l,PatRoachm,GarySternn, Heidi Swanson l, Shannon van der Velden l a Environment Canada, National Wildlife Research Centre, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H3, Canada b Centre d'études nordiques, Département de sciences biologiques, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec H3C 3J7, Canada c Faculty of Forestry and Environmental Management, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5A3, Canada d Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6N5, Canada e Environment Canada, Canada Centre for Inland Waters, Burlington, Ontario L7R 4A6, Canada f Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9, Canada g Environment Canada, Aquatic Contaminants Research Division, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 3H5, Canada h Gamberg Consulting, Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 5M2, Canada i Department of Geography, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC V8W 3R4, Canada j Lean Environmental, Apsley, Ontario K0L 1A0, Canada k Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada l Department of Biology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada m Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2B5, Canada n Centre for Earth Observation Science, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2, Canada HIGHLIGHTS • New data are available on mercury concentrations and fluxes in Arctic fresh waters. -

Beverly Caribou Herd Warning

Winter 2009 The Journal of Canadian Wilderness Canoeing Outfit 135 photo: Michael Peake Michael photo: In what can only be described as truly alarming. the massive Beverly Caribou Herd appears to be in precipitous decline. We examine the issue beginning with an urgent letter from Alex Hall on Page 2. Beverly Caribou We realize that many Che-Mun subscribers are aware of this situation and we feature many of your submissions to the Nunavut government to oppose the Uravan Mineral Garry Lake mining project on pages 4 and 5. The bull caribou above spent most of a day with us when we were camped on the Dis- Herd Warning mal Lakes in August 1991. He swam back and forth a couple of times and had a snooze in between. www.ottertooth.com/che-mun Winter Packet We know this general letter from Alex Hall is now a This story was picked up on Monday, Dec. 1 by industry that mineral development on the calving bit dated for email submissions but felt it was an the Canadian Press, CBC, and a number of newspa- grounds is out of the question. To do otherwise is to excellent synopsis of a disturbing story. pers across Canada, including our national newspa- accept the decline of the caribou population as unim- per, “The Globe & Mail”. The fate of the Beverly portant to people who depend on these animals, both ear Canoeing Companions: I need your Herd is a crushing blow, but no real surprise to me physically and culturally. These caribou provide mil- help. More accurately, the Barren Lands because for the past three of four summers we have lions of dollars worth of meat annually to the resi- and the caribou need your help; so I’m ask- seen virtually no caribou on our canoe trips. -

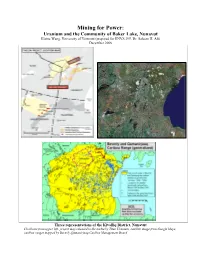

Mining for Power: Uranium Mining in Baker Lake Nunavut

Mining for Power: Uranium and the Community of Baker Lake, Nunavut Elaine Wang, University of Vermont (prepared for ENVS 295, Dr. Saleem H. Ali) December 2006 Three representations of the Kivalliq District, Nunavut Clockwise from upper left: project map released to the media by Titan Uranium; satellite image from Google Maps; caribou ranges mapped by Beverly-Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board “The Kiggavik Project near Baker Lake never went ahead. It is possible that, because of changing market conditions and the superior ore grades in neighboring Saskatchewan, 1989-90 had provided a window of opportunity for its development that was never to be repeated.” -Robert McPherson 2003, New Owners in the Own Land adapted from Cameco Corporation, 2006; not constant dollars Introduction In a plebiscite held on March 26, 1990, residents of the hamlet of Baker Lake (in what was then the District of Keewatin, Northwest Territories, now the District of Kivalliq, Nunavut, Canada), voted overwhelmingly against the development of a uranium mine by Urangesellschaft Canada Ltd. (UG) at a nearby site called Kiggavik, part of what prospectors know as the Thelon Basin. As a result, UG never explored its claims. In August of the same year, Bob Leonard, the president of the Keewatin Chamber of Commerce stated, “We are in an economic crisis. The economy in the Keewatin is in a mess. We are totally dependent on government spending and there’s no way that can continue.”1 The opening quote by Robert McPherson, a mining consultant in the Nunavut land claims negotiations, suggests that as recently as 2003, uranium mining near Baker Lake was, for many reasons, considered a non-option. -

Abandonment and Restoration Plan for Karrak Lake Research Station and F-14 Satellite Camp, Nunavut

Abandonment and Restoration Plan for Karrak Lake Research Station, F-14 Satellite Camp (Karrak River Camp), and Perry River Camp, Nunavut January 2015 This amended Abandonment and Restoration Plan is in effect as of 1 May 2015. It applies specifically to lands under administration of Environment Canada, located at: Karrak Lake Research Station: 67º 14’ 14” N and 100º 15’ 33” W F-14 Satellite Camp: 67º 21’ 09” N and 100º 20’ 59” W Perry River Camp: 67º 41’ 41” N and 102º 11’ 27” W Final Restoration The final restoration at both of the above-mentioned locations will commence once research programs are complete. All work under this plan will be complete prior to the date of expiry of all water licenses, land use, and sanctuary entrance permits. Photos of restored areas will be taken. The details of restoration are as follows: Fuel cache: All fuels (jet a, gasoline, naphtha, lubricating oils and fluids) and empty drums will be removed from the site. Contaminated soil, if present, will be handled as stated in the Spill Contingency Plan. Buildings: All buildings on sites are constructed of lumber, and will be combusted. Open burning is currently not permitted as per Land Use Permit N2014N0021 or Water License 3BC-KAR1316, but as per discussions with Sean Joseph (NWB) and Eva Paul (AANDC) in November-December 2014, we will request permission for open burning of painted lumber for a specified period upon abandonment of sites. Chemicals, metals, and other non-combustible materials: All chemicals such as paints, adhesives, etc., of which there is very little, will be removed from the site. -

Historical Developments in Utkuhiksalik Phonology; 5/16/04 Page 1 of 36

Carrie J. Dyck Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s NL A1B 3X9 Jean L. Briggs Department of Anthropology Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s NL A1B 3X9 Historical developments in Utkuhiksalik phonology; 5/16/04 page 1 of 36 1 Introduction* Utkuhiksalik has been analysed as a subdialect of Natsilik within the Western Canadian Inuktun (WCI) dialect continuum (Dorais, 1990:17; 41). 1 While Utkuhiksalik has much in com- mon with the other Natsilik subdialects, the Utkuhiksalingmiut and the Natsilingmiut were his- torically distinct groups (see §1.1). Today there are still lexical (see §1.2) and phonological dif- ferences between Utkuhiksalik and Natsilik. The goal of this paper is to highlight the main phonological differences by describing the Utkuhiksalik reflexes of Proto-Eskimoan (PE) *c, *y, and *D. 1.1 Overview of dialect relations2 The traditional territory of the Utkuhiksalingmiut (the people of the place where there is soapstone) lay between Chantrey Inlet and Franklin Lake. Utkuhiksalik speakers also lived in the * Research for this paper was supported by SSHRC grant #410-2000-0415, awarded to Jean Briggs. The authors would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the Utkuhiksalingmiut who presently live in Gjoa Haven, especially Briggs’s adoptive mother and aunts. Tape recordings of these consultants, collected by Briggs from the 1960’s to the present, constitute the data for this paper. Briggs is currently compiling a dictionary of Utkuhiksalik. 1 We use the term Natsilik, rather than Netsilik, to denote a dialect cluster that includes Natsilik, Utkuhik- salik, and Arviligjuaq. -

Canadian Heritage Rivers System Management Plan for the Thelon River, N.W.T

CANADIAN HERITAGE RIVERS SYSTEM MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE THELON RIVER, N.W.T. Sector Tourism I 11-40.12 Plans/Strategies I I I - CANADIAN HERITAGE RIVERS SYSTEM MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE THELON RIVER, N.W.T. NWT EDT Can The 1990 — CANADIAN HERITAGE RIVERS SYSTEM MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE THELON RIVER, N. W.T. Submitted by the Municipality of Baker Lake; the Department of Economic Development and Tourism Government of the Northwest Territories; and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development of Canada 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS . 1.0 Introduction . 1.1 Thelon Heritage River Nomination . 1 1.2 Regional Setting and River Description . 1 1.3 Canadian Heritage Rivers System . 4 1.4 Purpose of the Management Plan . 4 l.4.1 General Considerations . 4 1.4.2 Objectives of the Thelon River Management Plan. 5 2.0 Background 2.1 History of the Nomination . 6 2.2 Public Support and Consultation . 6 2.3 Present Land Use . 8 2.3. lBaker Lake Inuit Land Use . 8 2.3.2 Land Tenure and Land Claims . 8 2.3.3 Mining and Other Development . 10 3.0 Heritage Values 3.1 Natural Heritage Values . 11 3.2 Human Heritage Values . 12 3.3 Recreational Values . 13 4.0 Planning and Management Program 4.1 Land Use Framework.. ~ . 15 4.1. 1 River Corridor . 15 4.1.2 Areas of Significance . 15 4.1.3 Potential Territorial Parks . 18 4.2 Heritage Management and Protection . 20 4.2.1 Human Heritage . 20 4.2.2 Natural Heritage . 21 4.2. -

A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66

INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66 JUNE 2018 INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES 1 Kitinanaskimotin / Qujannamiik / Marcee / Miigwech: To all the Indigenous youth and organizations who took the time to share their ideas, experiences, and perspectives with us. To Assembly of Se7en Generations (A7G) who provided Indigenous Youth Voices Advisors administrative and capacity support. ANDRÉ BEAR GABRIELLE FAYANT To the Elders, mentors, friends and family who MAATALII ANERAQ OKALIK supported us on this journey. To the Indigenous Youth Voices team members who Citation contributed greatly to this Roadmap: Indigenous Youth Voices. (2018). A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66. THEA BELANGER MARISSA MILLS Ottawa, Canada Anishinabe/Maliseet Southern Tuschonne/Michif Electronic ISBN Paper ISBN ERIN DONNELLY NATHALIA PIU OKALIK 9781550146585 9781550146592 Haida Inuk LINDSAY DUPRÉ CHARLOTTE QAMANIQ-MASON WEBSITE INSTAGRAM www.indigenousyouthvoices.com @indigenousyouthvoices Michif Inuk FACEBOOK TWITTER WILL LANDON CAITLIN TOLLEY www.fb.com/indigyouthvoices2 A ROADMAP TO TRC@indigyouthvoice #66 Anishinabe Algonquin ACKNOWLEDGMENT We would like to recognize and honour all of the generations of Indigenous youth who have come before us and especially those, who under extreme duress in the Residential School system, did what they could to preserve their language and culture. The voices of Indigenous youth captured throughout this Roadmap echo generations of Indigenous youth before who have spoken out similarly in hopes of a better future for our peoples. Change has not yet happened. We offer this Roadmap to once again, clearly and explicitly show that Indigenous youth are the experts of our own lives, capable of voicing our concerns, understanding our needs and leading change. -

Baker Lake HTO Presentation on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit of Caribou Habitat

Baker Lake Hunters and Trappers Organization Presentation to Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Caribou Habitat Workshop November 4th, 2015 Iqaluit, Nunavut Basil Quinangnaq and Warren Bernauer Introduction • The Baker Lake Hunters and Trappers Organization (HTO) has requested mining and exploration activity be banned in caribou calving grounds and at important caribou water crossings. • This request is based on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit – the traditional knowledge and teachings passed on from generations, and the wisdom and values of Baker Lake Elders • Baker Lake hunters and Elders have been fighting to protect these areas for decades • In September 2015, the Baker Lake HTO held a workshop with hunters and Elders, to discuss and share knowledge about these sensitive areas • In preparation for the workshop, Warren Bernauer conducted background research for the HTO. Warren wrote a report summarizing the documented knowledge of these areas, the importance of these areas to Inuit, and the long history of Baker Lake hunters fighting to protect these areas. Caribou Water Crossings • Caribou water crossings are some of the most important areas for caribou hunting for Baker Lake Inuit, both historically and today. • Caribou are very sensitive to disturbance at water crossings. • Inuit have many traditional rules for how water crossings should be treated. o Do not walk, hunt, skin animals, cache meat or camp on the side of the river where caribou enter the water. Even footprints will disturb caribou. o Camp upstream from water crossings; camps should not be visible from the crossing o Clean up all animal remains near a crossing. Even blood on the ground should be buried. -

Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism

NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut Ministère de l’Environnement Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY • Gjoa Haven INVENTORY RESOURCE COASTAL NUNAVUT Ministère de l’Environnement Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory – Gjoa Haven 2011 Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division Box 1000 Station 1310 Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 GJOA HAVEN Inventory deliverables include: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • A final report summarizing all of the activities This report is derived from the Hamlet of Gjoa Haven undertaken as part of this project; and represents one component of the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory (NCRI). “Coastal inventory”, as used • Provision of the coastal resource inventory in a GIS here, refers to the collection of information on coastal database; resources and activities gained from community interviews, research, reports, maps, and other resources. This data is • Large-format resource inventory maps for the Hamlet presented in a series of maps. of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut; and Coastal resource inventories have been conducted in • Key recommendations on both the use of this study as many jurisdictions throughout Canada, notably along the well as future initiatives. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. These inventories have been used as a means of gathering reliable information on During the course of this project, Gjoa Haven was visited on coastal resources to facilitate their strategic assessment, two occasions: -

Re-Evaluation of the Northern Kivalliq Muskoxen (Ovibos Moschatus) Distribution, Abundance and Total Allowable Harvests in Muskox Management Unit MX-10

Re-evaluation of the Northern Kivalliq Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) Distribution, Abundance and Total Allowable Harvests in muskox management unit MX-10 Final Technical Report Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment Arviat, Nunavut, Canada. For submission to the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board 2019 Prepared by: Mitch W Campbell1 and David S. Lee2 1Nunavut Department of Environment, Arviat, Nunavut. 2Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. Department of Environment 1 Campbell, M.W. & D.S. Lee (2019) Introduction / Summary Prior to the enactment of protection in 1917 (Burch, 1977), muskox subpopulations throughout the central Arctic were hunted to near extirpation. Muskox populations within Nunavut are currently re-colonizing much of their historical range (Fournier and Gunn, 1998; Campbell, 2017), but there remain gaps in information on the status of muskox subpopulations in the area collectively known as the Northeastern Mainland north of the Thelon River, Baker Lake, and Chesterfield Inlet where the Northern Kivalliq Muskox subpopulation (NKMX) resides, within the MX-10 muskox management unit (Figure 1). This subpopulation is part of a greater population in Kivalliq which also includes the subpopulation south of MX-10, the Central Kivalliq Muskox (CKMX) in management unit MX-13. At its greatest extent, the distribution of muskox in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut occurred within an area extending south of 66o latitude, west to the Northwest Territories (NWT)/Thelon Game Sanctuary boundaries, east to the Hudson Bay coast line and south to the Manitoba border (Barr, 1991). Survey work conducted within the last 20 years has indicated a range expansion of Kivalliq muskox subpopulations to the northeast, east, and south of their historical range (Campbell, 2017) (Figure 2). -

Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical Support for Leading-Edge Scientific Research in Canada and Its Arctic

Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 LOGISTICAL SUPPORT FOR LEADING-EDGE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN CANADA AND ITS ARCTIC Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Contact information Polar Continental Shelf Program Natural Resources Canada 2464 Sheffield Road Ottawa ON K1B 4E5 Canada Tel.: 613-998-8145 Email: [email protected] Website: pcsp.nrcan.gc.ca Cover photographs: (Top) Ready to start fieldwork on Ward Hunt Island in Quttinirpaaq National Park, Nunavut (Bottom) Heading back to camp after a day of sampling in the Qarlikturvik Valley on Bylot Island, Nunavut Photograph contributors (alphabetically) Dan Anthon, Royal Roads University: page 8 (bottom) Lisa Hodgetts, University of Western Ontario: pages 34 (bottom) and 62 Justine E. Benjamin: pages 28 and 29 Scott Lamoureux, Queen’s University: page 17 Joël Bêty, Université du Québec à Rimouski: page 18 (top and bottom) Janice Lang, DRDC/DND: pages 40 and 41 (top and bottom) Maya Bhatia, University of Alberta: pages 14, 49 and 60 Jason Lau, University of Western Ontario: page 34 (top) Canadian Forces Combat Camera, Department of National Defence: page 13 Cyrielle Laurent, Yukon Research Centre: page 48 Hsin Cynthia Chiang, McGill University: pages 2, 8 (background), 9 (top Tanya Lemieux, Natural Resources Canada: page 9 (bottom -

Qikiqtani Region Arctic Ocean

OVERVIEW 2017 NUNAVUT MINERAL EXPLORATION, MINING & GEOSCIENCE QIKIQTANI REGION ARCTIC OCEAN OCÉAN ARCTIQUE LEGEND Commodity (Number of Properties) Base Metals, Active (2) Mine, Active (1) Diamonds, Active (2) Quttinirpaaq NP Sanikiluaq Mine, Inactive (2) Gold, Active (1) Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions 10 CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply ISLANDS Belcher MBS Migratory Bird Sanctuary NP National Park Nares Strait Islands NWA National Wildlife Area - ÉLISABETH Nansen TP Territorial Park WP Wildlife Preserve WS Wildlife Sanctuary Sound ELLESMERE ELIZABETHREINE ISLAND Inuit Owned Lands (Fee simple title) Kane Surface Only LA Agassiz Basin Surface and Subsurface Ice Cap QUEEN Geological Mapping Programs Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office ÎLES DE Kalaallit Nunaat Boundaries Peary Channel Müller GREENLAND/GROENLAND NLCA1 Nunavut Settlement Area Ice CapAXEL Nunavut Regions HEIBERG ÎLE (DENMARK/DANEMARK) NILCA 2 Nunavik Settlement Area ISLAND James Bay WP Provincial / Territorial D'ELLESMERE James Bay Transportation Routes Massey Sound Twin Islands WS Milne Inlet Tote Road / Proposed Rail Line Hassel Sound Prince of Wales Proposed Steensby Inlet Rail Line Prince Ellef Ringnes Icefield Gustaf Adolf Amund Meliadine Road Island Proposed Nunavut to Manitoba Road Sea Ringnes Eureka Sound Akimiski 1 Akimiski I. NLCA The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Island Island MBS 2 NILCA The Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement Norwegian Bay Baie James Boatswain Bay MBS ISLANDSHazen Strait Belcher Channel Byam Martin Channel Penny S Grise Fiord